John Gordon of Glenbucket

John Gordon of Glenbucket (c.1673 – 16 June 1750) was a Scottish Jacobite, or supporter of the claim of the House of Stuart to the British throne. Laird of a minor estate in Aberdeenshire, he fought in several successive Jacobite risings. Following the failure of the 1745 rising, in which he served with the rank of Major-General, he escaped to Norway before settling in France, where he died in 1750.

John Gordon of Glenbucket | |

|---|---|

.jpeg.webp) A contemporary drawing of Glenbucket during the 1745 rising; he was described as riding a "little grey Highland beast".[1] | |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Glenbucket" |

| Born | 1673 Aberdeenshire |

| Died | 16 June 1750 Boulogne |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Jacobite Major General |

| Unit | Glenbucket's Regiment |

| Battles/wars | 1689 Jacobite Rising Killiecrankie 1715 Jacobite Rising Dunfermline Sheriffmuir 1745 Jacobite Rising Culloden |

Despite a reputation in later popular history as “one of the most romantic of Jacobite heroes”,[2] Glenbucket was a controversial figure who acted as a government agent between 1715 and 1745, and was accused of forcibly conscripting men during the 1745 rising.

Early life

Glenbucket was born in 1673 into an obscure junior branch of the Gordon family; his grandfather, George, had held the tack of Noth. His father, John Gordon of Knockespock (c.1654-1704) purchased the small estate of Glenbucket, near Kildrummy on the border of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire, in 1701 from another branch of the Gordons.[3]

At the age of sixteen Glenbucket supposedly fought on the Jacobite side at Killiecrankie;[4] the battle was a Jacobite victory but their commander, John Graham of Claverhouse, was killed in its closing minutes and the rising later collapsed. Little else is known of his early life other than that he attended King's College, Aberdeen at the same time as Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat.

1715 rising

The 1715 Jacobite rising was sparked by the power struggle between the Whig and Tory factions of Parliament in the wake of Queen Anne's death: it was initiated by the Tory Earl of Mar, without the approval of the Jacobite claimant James Stuart, after George I deprived him of his offices. Glenbucket served as bailie to the Marquess of Huntly, later 2nd Duke of Gordon, which included an obligation to provide military service. When Huntly joined the Rising, Glenbucket raised men in Strathbogie and commanded one of the two Gordon battalions at the inconclusive Battle of Sheriffmuir.[5]

Following the collapse of the Rising, Glenbucket and his men surrendered to his neighbour Ludovick Grant at Strathbogie on 6 March 1716 and Huntly intervened on his behalf, suggesting his local influence could be of use to the government.[3] Grant passed this recommendation onto the government commander William Cadogan, who told Glenbucket that rebels must be imprisoned but treated him “most civilie”.[6]

Initially held in Edinburgh Castle, Glenbucket's preferential treatment there led to a complaint by the Lord Justice Clerk; he was moved to Carlisle and released without being charged in late 1716.[7] The new commander in Scotland, Lieutenant-General Carpenter, reported he expressed "the highest gratitude and loyalty, protesting he will employ his whole life to do his Majesty and the Government the best service he can".[8]

As bailie for the Gordon estates, Glenbucket gained considerable influence over large areas of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire and both Jacobites and the government sought his backing during the 1719 rising. Its centrepiece was a proposed Spanish landing in South-West England but only the subsidiary rising in Scotland actually took place. The Jacobite Lord Tullibardine wrote to Glenbucket on 15 April 1719 urging him to join but he refused, instead providing Carpenter with regular reports on rebel activities.[9] The attempt ended with Jacobite defeat at Glen Shiel in June.

Bailies were rarely popular with all tenants and in March 1724, Glenbucket was seriously wounded by men from Clan Macpherson. He fought them off but Huntly, now Duke of Gordon, sent a large party of armed men into the district and since Lachlan Macpherson (1673-1746) was also a Jacobite sympathiser, both sides sought support from the exiles. In a letter to George Keith, Macpherson claimed Glenbucket was "a person capable of executing anything, however desperate", while James wrote to Gordon expressing concern at the attack on "honest Glenbucket", but advised caution in punishing the Macphersons as "you would be sorry to deprive me and the good cause of so many brave men".[10] Attempts by Gordon to bring the perpetrators to justice were still ongoing in 1728.

Further Jacobite activity

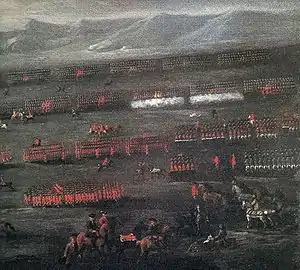

.jpg.webp)

Around this time, Glenbucket began regular contact with the Stuart exiles; this was hardly unusual and many Scots and English peers did the same, as an insurance policy. One factor may have been the death in 1728 of the Catholic 2nd Duke of Gordon, who was succeeded by his Protestant son, Cosmo 3rd Duke of Gordon; using Glenbucket to indirectly maintain links with the exiled Stuarts provided distance. It also coincided with an improvement in Jacobite prospects for the first time in over two decades, as French and Spanish statesmen looked for ways to reduce the expansion of British commercial strength.[11]

Glenbucket proposed a rising in Scotland, supported by French regulars from the Irish Brigades, arguing this could successfully resist the small number of government troops stationed there.[12] He sold his estate in 1737, using the proceeds to finance a trip to Europe; in January 1738, he met with James, then living quietly in Rome having “abandoned all hope of a Restoration”.[12] James listened and gave him a Major-General’s commission but remained unconvinced.[13] Glenbucket then went to Paris and presented his plan to Cardinal Fleury, chief French minister from 1723 to 1743, who gave him a hearing but nothing else; like the vast majority of French statesmen, he viewed the Jacobites as unreliable fantasists.[14]

Scepticism in Paris and Rome was mirrored by that within the Scottish Jacobite community, which remained riven by divisions going back to 1688. As a member of the minority Catholic faction, there was little support for Glenbucket's plan: John Murray of Broughton, appointed principal Jacobite agent in 1741, later characterised him as “a man of no property nor natural following, of very mean understanding, with a vast deal of vanity”.[15] Several prominent Jacobites sent a letter to Fleury in 1740 pledging their support, including Donald Cameron of Lochiel and the Duke of Perth, but Glenbucket was not a signatory.[13]

When Fleury died in 1743, Louis XV of France took over government; he planned an invasion of England in early 1744 to restore the Stuarts and to avoid incriminating Gordon in his pro-Jacobite activities, Glenbucket resigned as his factor in March 1744.[16] Shortly after this, the plan was abandoned when winter storms scattered and sank the French invasion fleet but the Stuart heir Charles Edward continued to plan an expedition to Scotland in the summer of 1745. He relied on promises of support from a small number of clan chiefs in the western Highlands but ignored their stipulation this was conditional he provided French troops, money and weapons; without these, most Scottish Jacobites, including Murray of Broughton, attempted to dissuade him.

1745 rising

Charles landed in Scotland in late July 1745, accompanied only by seven companions. Most of those he contacted advised him to return, but Lochiel and a few other influential figures were persuaded, providing Charles with the nucleus of the Jacobite army.

The government seems to have believed that Glenbucket would not join Charles: “I have some confidence in my old friend Glenbucket’s prudence and temper,” wrote Lord President Forbes on 14 August, though by September Sir Harie Innes commented “we are in perpetual alarm for Glenbucket – he took some of the Duke of Gordon’s horses this morning”.[13] In fact, he was the first of the eastern lairds to join the rising, having been present at Glenfinnan on 19 August when Charles raised his standard.[17] Returning to Banffshire with a small party of Highlanders, he began raising men in Glenlivet, allegedly by threatening them “with being plundered if they did not join”.[18] He continued recruiting across Banffshire and by mid September his unit had grown to regimental size, around 300 strong, though Forbes commented that his men “desert him daily”.[18] By the time he joined the main Jacobite force at Edinburgh on 4 October, he had about 400 men.[19]

Despite being well into his seventies, and despite being reported dead in October,[21] Glenbucket played an active role in the campaign. Though Lord George Murray described him as “very infirm”, Sir John MacDonald claimed that he was “the only Scot I ever knew who was able to start at the hour fixed, he was also the most active.”[22]

Glenbucket’s regiment joined the Jacobite invasion of England in November 1745, marching as part of Perth’s division. The Jacobites marched rapidly as far as Derby, but against Charles's wishes then decided to retreat to Scotland as there was no sign of the English support or the French invasion force Charles had promised. The retreat was conducted successfully; Lord George Murray later recorded Glenbucket was present at the rearguard action at Clifton on 18 December. About 50 of Glenbucket’s men were left with the garrison of Carlisle, under captains George Abernethy and Alexander Leith; after a short siege the garrison surrendered to the government army on 30 December.[lower-alpha 1][23]

In January 1746 the Jacobites besieged Stirling Castle. Glenbucket commanded the blockading troops until the Battle of Falkirk Muir, fought against a government relief force on 15 January, after which he was replaced by the Duke of Perth. The siege was abandoned shortly afterwards and in February, while his regiment marched northwards through Aberdeenshire, Glenbucket and a party of Highlanders besieged Ruthven Barracks.[24] Towards the end of February he was reported to be back with his regiment and recruiting in a remote area around Glenlivet and Strathdon.

Increasingly short of money and supplies the Jacobites withdrew to Inverness. When the government army advanced from Aberdeen on 8 April, the Jacobite leadership were mostly in favour of standing and fighting, but in the ensuing Battle of Culloden on 16 April they were comprehensively defeated. Glenbucket and his regiment were initially positioned in the second line; some authors have suggested that they retreated in good order to Badenoch and disbanded there, but given that they were not far from their own country they are more likely to have simply dispersed after the battle.[25]

Glenbucket himself escaped; In June he was again reported “dead lately in the hills of Glenavon”[21] but was able to leave Scotland in November on a Swedish ship. After some time in Norway he made his way to the Jacobite exile community in Paris, where he complained of living in poverty despite receiving a small number of ‘gratification’ payments from the French. He requested accommodation in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, but this was refused; he died in 1750 at Boulogne.[21]

Family and legacy

Glenbucket was married to Jean Forbes. He had a number of children, several of whom were officers in his regiment; the eldest, John, was involved in the 1745 rising along with his own eldest son William and was taken prisoner, though later claimed to be almost completely blind; he was released in 1747.

His second son David Gordon of Kirkhill, described by one observer as "an insignificant creature",[26] accompanied him during his recruiting efforts but died in March 1746. The third, George Gordon, was taken prisoner, later escaping and travelling to Jamaica where he became a physician.[22] Another son, Alexander, obtained a post in the Imperial Russian Navy through the influence of Admiral Thomas Gordon; he was killed in action in 1739.

Glenbucket had cultivated his connections with other Jacobite families, particularly in the Highlands: a contemporary commented he was "the only instance of a Gentleman of a low country family and education, that both could and would so thoroughly conform himself to the Highland spirit and manners, as to be able to procure a following among them without a Highland estate".[27] One of his daughters, Helen, married John Macdonell, 12th chief of Glengarry; another daughter Isabel married Donald Macdonell of Lochgarry, colonel of Glengarry's regiment in 1745.

His long service as a Jacobite rebel meant that "Old Glenbucket" was a central figure in the romanticised popular history of Jacobitism; a popular though unlikely story is that he used to give King George II nightmares.[28] A more balanced assessment of his career reveals "a very brave man but perhaps [...] a little too 'canny'".[29]

References

- At their trials Abernethy and Leith, both Banffshire men, claimed to have been forcibly impressed by Glenbucket; Abernethy was found guilty but reprieved, whereas Leith was executed at Kennington Common in November

- Reid, Stuart (2012) The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745–46, Bloomsbury, p.11

- Tayler, Henrietta. “John Gordon of Glenbucket”, Scottish Historical Review, (1948) v27, 10, p.165

- German, Kieran. John Gordon of Glenbucket, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- Lenman, Bruce. (1980) The Jacobite Risings in Britain, Methuen, p.233

- Reid, Stuart. (2014) Sheriffmuir 1715, Casemate, p.160

- Tayler, (1948), p.168

- Tayler (1948), p.169

- Tayler (1948), p.171

- Tayler (1948) p.172

- Glover (ed). (1847) The Stuart Papers. Printed from the Originals in the Possession of Her Majesty the Queen, v.1, Wright, pp.100-105

- McKay, Derek (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815. Routledge. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0582485549.

- Blaikie, Walter (1916) Origins of the Forty-Five, Scottish History Society, xlix-li

- Tayler (1948), p.173

- Zimmerman, Doron (2003). The Jacobite Movement in Scotland and in Exile, 1749–1759. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 51. ISBN 978-1403912916.

- Blaikie (1916), li

- German, Kieran (2013). "Gordon, John, of Glenbucket". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online 2014 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/105513. ISBN 9780198614111. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Grant, Charles. “Glenbucket’s Regiment of Foot” in Journal of the Society for Army Historical Researc, v.28, 113 (Spring 1950), p.31

- Grant (1950) p.32

- Grant (1950) p.34

- Grant (1950) p.33

- Tayler (1948) p.174

- Grant (1950) p.41

- Grant (1950) p.36

- Grant (1950) p.38

- Grant (1950) p.40

- Blaikie (1916), p.114

- Blaikie (1916) p.115

- Barclay, W. Cambridge County Geographies: Banffshire, Cambridge UP, p.80

- Tayler (1948) p.175

Sources

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1916). Origins of the 'Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising. T. and A. Constable at the Edinburgh University Press for the Scottish History Society. pp. xlix. OCLC 2974999.

- German, Kieran (2014). "Gordon, John, of Glenbucket". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/105513. ISBN 9780198614111. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Grant, Charles (1950). "Glenbucket's Regiment of Foot". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 28 (113).

- Lenman, Bruce (1980). The Jacobite Risings in Britain 1689–1746. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0413396501.

- Reid, Stuart (2012). Cumberland's Culloden Army 1745-46. Osprey. ISBN 978-1849088466.

- Reid, Stuart (2014). Sheriffmuir 1715. Casemate. ISBN 9781473839441.

- Tayler, Henrietta (1948). "John Gordon of Glenbucket". The Scottish Historical Review. 27 (104).