John Pender

Sir John Pender KCMG GCMG FSA FRSE (10 September 1816 – 7 July 1896) was a Scottish submarine communications cable pioneer and politician.

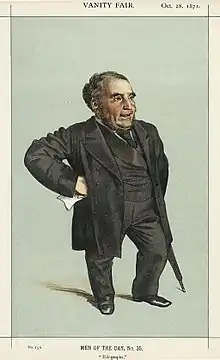

Pender as caricatured by James Tissot in Vanity Fair, October 1871

Early life

He was born in the Vale of Leven, Scotland, the son of James Pender and his wife, Marion Mason. He was educated at Glasgow High School. He became a successful merchant in textile fabrics, first in Glasgow, then in Manchester (where he had a warehouse in Peter Street near The Great Northern Warehouse). He lived at Middleton Hall, County Linlithgow, Foots Cray Place, Sidcup, Kent, and Arlington House, 18 Arlington Street London.

Telegraph companies

In London 1866, John Pender was the leading financier/director and Chairman of the Companies involved who, with his colleagues, undertook the first successful laying of the transatlantic cable from Valentia Island off the coast of Ireland to Heart's Content, Newfoundland and Labrador. This cable was the most successful and commercially viable of all the transatlantic cables and was 100% British financed, unlike the previous transatlantic cable-laying attempts, which had had some financial backing from American Investors. The Anglo-American Telegraph Company (formerly the Atlantic Telegraph Company) and The Gutta Percha Company and Glass, Elliott (Greenwich, London) merged into the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company 'Telcon' (which was taken over decades later by British Insulated Callender's Cables), and laid the first successful cable in 1866 and ended up manufacturing and laying all of Eastern Telegraph's cables and most of the submarine telegraph cables of the rest of the world. [1]

He founded 32 telegraph companies, including Eastern Telegraph, Eastern and South African Telegraph, Western Telegraph Europe and Azores Telegraph Company, Australasia and China Telegraph Company, London Platino-Brazilian Telegraph Company, Pacific and European Telegraph Company which later became Cable & Wireless. In 1934, Imperial and International Communications, formerly the Eastern Telegraph Company (the amalgamation of those 32 telegraph companies), became Cable & Wireless. The new name was designed to more clearly reflect the combined radio and cable services which it offered, without reference to the Empire. Cable & Wireless is one of the world's leading international communications companies. It operates through two standalone business units. International and Europe, Asia & U.S.

Parliament

He represented Totnes in parliament as a Liberal MP in 1862 to 1866 (the seat was disenfranchised by the Reform Act 1867), and Wick Burghs from 1872 until his defeat in 1885. He was unsuccessful Liberal Unionist candidate in Wick Burghs in 1886 and in Govan at the by-election in 1889, and again represented Wick Burghs from 1892 to 1896. He was made a K.C.M.G. in 1888 and was promoted in 1892 to be G.C.M.G.[1]

His eldest son James (b. 1841) Sir James Pender, 1st Baronet, who was MP. for Mid Northamptonshire in 1895–1900, was created a baronet in 1897; and his third son, John Denison-Pender (b. 1855), was created a K.C.M.G. in 1901, the year in which he was living at Footscray Place in Sidcup.

Railways and paintings

Pender also had interests in railways and was persuaded to invest in the Isle of Man Steam Railway. As a result of this, No. 3 was named Pender in his honour. He was a director of the Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railway in the United States, which connected major midwestern cities and stimulated their economies.[2] In 1883 he founded Yule Ranch in western North Dakota.[3] Pender, Nebraska was named for him.[2]

He also amassed a considerable collection of paintings, including some of the works of J. M. W. Turner, including Giudecca La Donna Della Salute and San Georgio, a view of Venice. Exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1841 and arguably Turner's best work, it was sold in 1897 for 1,650 guineas to Donald Currie. A century later it broke all auction records for works by a British artist when it was sold to Steve Wynn (entrepreneur) through Christie's (New York) for US$35.8 Million in April 2006 This painting is one of four of Turner's paintings of Venice to be in private hands. Also in Pender's collection were the works An Event in the forest by Landseer, 'Portrait of Princess Sobieski' by Joshua Reynolds, and works by John Everett Millais, Gainsborough, and Canaletto. The collection was sold in parts the year after John Pender's death.

Family relationships

At the time of his death, which occurred at Foots Cray Place, Kent, on 7 July 1896, he controlled companies having a capital of 15 million sterling and owning 73,640 nautical miles (136,380 km) of cables (one third of the cables in the world), these cables formed the base of the networks that years later developed into the World Wide Web.

Pender was married twice: firstly in 1840 to Marion Cairns, who died giving birth to his son Henry in 1841 (their eldest son James survived); and in 1851 he married Emma Denison (d.1890). They also had a son John Denison Pender (1855–1929) and two daughters Marion Denison Pender (1856–1955), who married George William Des Voeux, and Anne Denison Pender (1853–1902). The girls were painted in an Aesthetic Movement portrait titled "Leisure Hours" by John Everett Millais in 1864 Detroit Institute of Arts. Pender is buried in the grounds of All Saints' Church, Rectory Lane Foots Cray with a fine but simple Celtic cross memorial, and is also remembered via the inauguration of the Pender Chair from the money raised by the memorial fund at the time of his death.

Anglo-American Telegraph Company

In the 1850s the United States supplied about three-quarters of Britain's cotton imports, more than 2 million bales per year; and as a cotton merchant Pender well understood the importance of transatlantic communication; he made his first fortune trading cotton. He was one of the 345 original investors who each risked a thousand pounds in the Transatlantic Cable in 1858, and when the Atlantic Telegraph Company was ruined by the loss of the 1865 cable he formed the Anglo-American Telegraph Company to continue the work, but it was not until he had given his personal guarantee for a quarter of a million pounds that the makers would undertake the manufacture of a new cable. In the end he was justified, and telegraphic communication with America became a commercial success.

Early submarine cables

The first working submarine cable had been laid in 1851 between Dover and Calais. Its design formed the basis of future cables: a copper conductor, the cable's core, was insulated with gutta-percha, a type of latex from Malaya which had been found preferable to India rubber for under-water use. The cable was armoured with iron wire, thicker at the shore ends where extra protection from anchors and tidal chafing was needed. Although this basic technology was in place, there was a world of difference between a cross-Channel line of less than twenty-five miles and a cable capable of spanning the Atlantic, crossing the 1,660 nautical miles (3,070 km) between Valentia, on the west coast of Ireland, and Newfoundland in depths of up to two miles (3 km). There were difficulties of scale, and also of electrical management. In long submarine cables, received signals were extremely feeble, as there was no way of amplifying or relaying them in mid-ocean. In 1858, in Newfoundland, using the first Atlantic Cable, it was taking hours and hours to send only a few words, with repeats necessary to try to interpret the weak signals that had to be detected with a candlelit mirror galvanometer on which earth currents registered higher than the actual signals. Three operators at a time had to stand and watch the beam trace on a wall at Newfoundland and make a majority guess about what the intended character was that was coming in.

The original sending voltage applied to the first Atlantic cable in 1858 had been about 600 volts. The British physician, Dr. Whitehouse, made one of the classic mistakes that is still today being made by telecommunications users, when the signals didn't get through, he raised the voltage. Lord Kelvin, the physicist director of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, had reservations, but he was overridden by the non-technical "chief electrician," Dr. Whitehouse. Whitehouse cobbled together apparatus to raise the sending voltage to about 2,000 volts, and the cable's insulation failed and blew apart. After only three months of use and a total of 732 messages, the first cable across the Atlantic Ocean went dead, apparently forever; and with thousands of investors losing their money 'in the sea.'

The Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company 'Telcon' came up with an improved cable design and built a new cable that was three times the diameter of the failed 1858 cable and weighed in at 9,000 tons in one 2,300-mile (3,700 km) piece. To handle this huge weight of copper and iron, Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company had to charter the largest ship in the world at the time, a ship sailors regarded as jinxed, the 700-foot-long (210 m) cargo ship originally named Leviathan, later named the Great Eastern, and fitted it out to be a cable ship.

Transatlantic cable

It took from January 1865 to that June to coil up the 2,300 miles (3,700 km) of cable in the three circular tanks of the SS Great Eastern. A crew of 500 was needed to operate the ship, of which 200 were needed merely to raise its anchor. Finally, on 23 July 1865 the Great Eastern started off from Valentia to attempt retracing the route of seven years earlier. This attempt was almost as problem-filled as the first failed one in 1858. Several times, faults were found in the wire as it was paid out, and the operation had to stop for cable repairs on deck. On 2 August, the cable broke after laying 1,186 miles (1,909 km) of cable, and the end was lost to the ocean floor. Dragging and grappling for it for nine days, and losing the end after snagging it twice, more than 2 miles (3.2 km) under the water, the attempt was abandoned on 11 August 1865, and the expedition turned back to England.

A major and sudden obstacle at the beginning of 1866 was the discovery that the Atlantic Telegraph Company, which had been established under an Act of Parliament in 1856, was acting outside its powers in trying to raise its capital by a further £600,000 to finance the 1866 expedition. There was no parliamentary time to amend the company's charter. To avoid another year's delay, Gooch and Pender established a new limited liability company, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company Ltd, to take over the project. Daniel Gooch and John Pender's actions saved the scheme. The balance of funds needed was secured through Telcon and the merchant bank of Morgan and Company only days before a stock market crash which might have ended any hopes of laying a cable that summer.

That year, 1866, the Great Eastern and its fleet set off again from Valentia Bay, Ireland, and started westward. The cable was, as in all previous attempts, operated from the deck of the ship, and was connected back through to England, so the English public knew of the progress. (This may have been the world's first press reports from the deck of a ship at sea, since in earlier attempts, the cable, while being operated, had not been connected through to shore.) After just two weeks and a relatively trouble-free run of laying 1,896 miles (3,051 km) of cable, the Great Eastern arrived offshore from Heart's Content, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. Being so large, the Great Eastern could not approach the shore closely, so a smaller ship took aboard the shore end to make the connection to the cable station.

On 27 July 1866 Daniel Gooch the cable laying engineer on board the Great Eastern, sent a message back down the cable just before cutting the shore end off for transport to the cable station, informing Edward Stanley, 15th Earl of Derby the British Foreign Secretary, that the New World was once again connected with the Old. Queen Victoria and President Andrew Johnson exchanged formal opening messages on 29 July 1866. The celebrations in America were muted in comparison with those of 1857, as war had recently ended, and the new Atlantic telegraph, much more than on previous expeditions, was now seen as a product of British work and capital. As to operating details, the speed of transmission was eight words per minute (a speed that many submarine telegraph cables operated at for decades afterwards), and the rate for twenty words or less, including address, date and signature, was $100 in gold or $150 in greenback banknotes, while additional words were $5 in gold, $7.50 in greenbacks each. Deep-sea cables, no longer a heroic struggle against the elements, had become instead a mature technology and a serious business.

As an aftermath to final success, Great Eastern sailed back to sea, and after 30 attempts managed to grapple the end of the 1865 cable it had lost the year before, splice to it, and lay a new end to Heart's Content. This meant that the first successful cable crossed the Atlantic on 27 July 1866 (with service to the U.S. on 29 July) was duplicated on 9 September 1866. So, the first successful route had two cables from very early days.

John Pender's contribution to the Atlantic venture, especially after 1862, had been substantial, and ultimately he had risked everything he owned on the 1866 attempt. Experience with the Atlantic line had shown Pender that intercontinental cables were no longer a gamble, that technical improvements had reduced them to an acceptable risk. Moreover, they could be exceptionally profitable. This encouraged him to continue promoting long-distance telegraphs, and the companies he launched during the following years laid cables to the Far East, Australasia and South America. Once a line was established, he followed a pattern of consolidating it into his parent company. Pender made another fortune, and was rewarded with his knighthood in 1888.

Nationalisation

In 1868 the British government decided to buy up all the inland telegraph companies, including English and Irish Magnetic, a process completed in 1870, but left overseas telegraphy in private hands. In 1869 John Pender created three more companies. The British-Indian Submarine Telegraph Company and the Falmouth, Gibraltar and Malta Telegraph Company completed the cable system between London and Bombay in 1870, while the China Submarine Telegraph company set about connecting Singapore and Hong Kong, Britain's main possessions in East Asia. Pender's other company, Telcon, supplied cable not only for these ventures but also for a cable from Marseilles to Malta, which provided France with a link to its colonies in North Africa and Asia. When the governments of South Australia and Queensland, Australia, decided that the monthly steamships between Australia and Britain were too slow a means of communication, it was John Pender whom they invited to fill the telegraphic gap between Bombay and Adelaide, Australia. The All-Sea Australia to England Telegraph, supplied by Telcon (which became British Insulated Callender's Cables), was opened in 1872. It was operated in two sections, Bombay to Singapore by the British India Extension Telegraph Company and Singapore to Adelaide by the British Australian Telegraph Company, both under Pender's control.

Reorganization

In 1872 Pender now set about reorganising his cable interests, first came the amalgamation of British Indian Submarine, Falmouth, Gibraltar and Malta, and the Marseilles, Algiers, and Malta companies with the Anglo-Mediterranean, which had been created in 1868 to link Malta, Alexandria, and the new Suez Canal. He became chairman of the Eastern Telegraph Company that resulted from their merger. Next, in 1873, he presided over the merger of his Australian, Chinese, and British India Extension companies into the Eastern Extension Australasia and China Telegraph Company. It was also in 1873 that Pender created a holding company, the Globe Telegraph and Trust Company. The holding company's investors received portions of shares in the operating companies, chiefly the Eastern Telegraph and the Anglo-American. All the companies so far named remained within the Eastern Telegraph group, except Anglo-American, which was taken over in 1910 by a U.S. firm, Western Union. Finally, 1873 also saw the creation of the Brazilian Submarine Telegraph Company, which had several directors and shareholders in common with Eastern Telegraph and opened a cable from Lisbon, Portugal, to Pernambuco, Brazil, in 1874.

Between 1879 and 1889 Pender's group added Africa to its list of cable routes through three companies, African Direct, a joint venture with Brazilian Submarine; West African, incorporated into Eastern Telegraph; and Eastern and South African. In 1892, following the expiration of the telegraph concession operated by Brazilian Submarine, that company and its main rival, Western and Brazilian, formed a new venture, the Pacific and European Telegraph Company, to renew the concession and link Brazil with Chile and Argentina. Having helped to arrange this operation, Pender became chairman of Brazilian Submarine in 1893, further reinforcing his position as the leading figure in the worldwide cable business. After John Pender died in 1896; his successor as chairman of Eastern Telegraph and Eastern Extension was Lord Tweeddale, while Pender's son John Denison-Pender, later Sir John, continued as managing director. The last stage in restructuring the set of companies Pender had been so instrumental in creating, came in 1899, when Brazilian Submarine, having absorbed two other London-based telegraph companies operating in South America, was renamed the Western Telegraph Company.

Effect of wireless

The first confrontation between cable and the new medium of wireless ended in acrimony. Guglielmo Marconi's success in sending a signal from Cornwall to Newfoundland in 1901 was soured when the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, part of the Pender group, forbade any further experiments, since they would infringe on the Pender group's monopoly of communications in Newfoundland. Marconi moved his work to Nova Scotia, and found the Americans and Canadians generally more receptive to his achievement than Europeans. Just years later their companies and technologies would merge.

Trustees, Executors and Securities Insurance Corporation, Limited

Together with City financiers Leopold Salomons and Jabez Balfour, Pender founded the investment underwriting firm the Trustees, Executors and Securities Insurance Corporation, Limited in December 1887.[4][5]

See also

- Pender v Lushington (1877) 6 Ch D 70

References

- Stronach 1901.

- Honoring Pender's 125th Anniversary, Legislative Resolution 570

- VVV Ranch - Weinreis Brothers entry, North Dakota Cowboy Hall of Fame

- Hawkins RA (2007). "American Boomers and the Flotation of Shares in the City of London in the Late Nineteenth Century". Business History. 49 (6): 802–822. doi:10.1080/00076790701710282. S2CID 153446872.

- Mira Wilkins (1989). The history of foreign investment in the United States to 1914. Harvard studies in business history. 41. Harvard University Press. p. 492. ISBN 0-674-39666-9.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pender, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pender, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stronach, George (1901). "Pender, John". Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stronach, George (1901). "Pender, John". Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co. - McConnell, Anita. "Pender, Sir John (1816–1896)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21831. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by John Pender

- Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Earl of Gifford Thomas Mills |

Member of Parliament for Totnes 1862–1867 With: The Earl of Gifford 1862–1863 Alfred Seymour 1863–1867 |

Succeeded by Alfred Seymour Other seat vacant, until disenfranchisement |

| Preceded by George Loch |

Member of Parliament for Wick Burghs 1872–1885 |

Succeeded by John Macdonald Cameron |

| Preceded by John Macdonald Cameron |

Member of Parliament for Wick Burghs 1892–1896 |

Succeeded by Thomas Hedderwick |