John Wilson (Scottish writer)

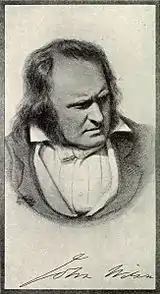

John Wilson of Elleray FRSE (18 May 1785 – 3 April 1854) was a Scottish advocate, literary critic and author, the writer most frequently identified with the pseudonym Christopher North of Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.

He was professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh from 1820–1851.

Life and work

Wilson was born in Paisley, the son of John Wilson, a wealthy gauze manufacturer who died in 1796, when John was 11 years old, and his wife Margaret Sym (1753–1825).[1][2] He was their fourth child, and the eldest son, having nine sisters and brothers.

He was educated at Paisley Grammar School and entered the University of Glasgow aged 12 (14 being the usual age at that time), and continued to attend various classes for six years, mostly under Professor George Jardine, with whose family he lived. During this period Wilson excelled in sport as well as academic subjects, and fell in love with Margaret Fletcher, who was the object of his affections for several years.[1] Fellow student Alexander Blair became a close friend.[3]

In 1803 Wilson was entered as a gentleman commoner at Magdalen College, Oxford. He was inspired by Oxford and in much of his later work, notably in the essay called "Old North and Young North", expresses his love for it. However his time at Oxford was not altogether happy. Though he obtained a brilliant first class degree, he made no close friends at Magdalen College and few in the university. Nor was he lucky in love, for his beloved Margaret Fletcher eloped to New York with his younger brother Charles.

Wilson took his degree in 1807, and at the age of 22 was his own master with a good income and no guardian to control him. He was able devote himself to managing his estate on Windermere called Elleray, ever since connected with his name. Here for four years he built, boated, wrestled, shot, fished, walked and amused himself, besides composing or collecting from previous compositions a considerable volume of poems, published in 1812 as The Isle of Palms. During this time he also befriended the literary figures William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and Thomas de Quincey.[1]

In 1811 Wilson married Jane Penny of Ambleside, daughter of the Liverpool merchant and slave trader James Penny, and they were happy for four years, until the event which made a working man of letters of Wilson, and without which he would probably have produced a few volumes of verse and nothing more. Most of his fortune was lost by the dishonest speculation of an uncle, in whose hands Wilson had carelessly left it. His mother had a house in Edinburgh, in which she was able and willing to receive her son and his family; he was not forced to give up Elleray, though he was no longer able to live there.[1]

He read law and was elected to the Faculty of Advocates in 1815, still with many outside interests, and in 1816 produced a second volume of poems, The City of the Plague. In 1817, soon after the founding of Blackwood's Magazine, Wilson began his connection with the Tory monthly and in October 1817 he joined with John Gibson Lockhart in the October number working up James Hogg's MS a satire called the Chaldee Manuscript, in the form of biblical parody, on the rival Edinburgh Review, its publisher and his contributors. He became the principal writer for Blackwood's, though never its nominal editor, the publisher retaining supervision even over Lockhart's and "Christopher North's" contributions, which were the making of the magazine.[1]

In 1822 began the series of Noctes Ambrosianae, after 1825 mostly Wilson's work. These are discussions in the form of convivial table-talk, including wonderfully various digressions of criticism, description and miscellaneous writing. There was much ephemeral, a certain amount purely local, and something occasionally trivial in them. But their dramatic force, their incessant flashes of happy thought and happy expression, their almost incomparable fulness of life, and their magnificent humour give them all but the highest place among genial and recreative literature. "The Ettrick Shepherd," an idealised portrait of James Hogg, one of the talkers, is a most delightful creation. Before this, Wilson had contributed to Blackwood's prose tales and sketches, and novels, some of which were afterwards published separately in Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life (1822), The Trials of Margaret Lyndsay (1823) and The Foresters (1825); later appeared essays on Edmund Spenser, Homer and all sorts of modern subjects and authors.[1][4]

Wilson left his mother's house and established himself (1819) in Ann Street, Edinburgh, with his wife and five children. His election to the chair of Moral Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh (1820) was unexpected, and the best qualified man in the United Kingdom, Sir William Hamilton, was also a candidate. But the matter was made a political one; the Tories still had a majority in the burgh council; Wilson was powerfully backed by friends, Sir Walter Scott at their head; and his adversaries played into his hands by attacking his moral character, which was not open to any fair reproach.[1]

Wilson made a very excellent professor, never perhaps attaining to any great scientific knowledge in his subject or power of expounding it, but acting on generation after generation of students with a stimulating force that is far more valuable than the most exhaustive knowledge of a particular topic.[5]

His duties left him plenty of time for magazine work, and for many years his contributions to Blackwood were voluminous, in one year (1834) amounting to over 50 separate articles. Most of the best and best known of them appeared between 1825 and 1835.[1]

In 1844, he published The Genius, and Character of Burns.

In his last 30 years, he spent his time between Edinburgh and Elleray, with excursions and summer residences elsewhere, a sea trip on board the Experimental Squadron in the English Channel during the summer of 1832, and a few other unimportant diversions. The death of his wife in 1837 was a severe blow to him, especially as it followed within three years of his friend Blackwood.[6]

Death and legacy

Wilson died at home at 6 Gloucester Place in Edinburgh on 3rd April 1854 as the result of a stroke.

He was buried on the southern side of Dean Cemetery on 7 April. A large red granite obelisk was erected at his grave.

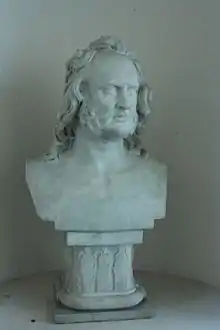

In 1865 a statue by Sir John Steell was erected to his memory in Princes Street Gardens. The bronze figure stands on a substantial stone pedestal and is located between the Royal Scottish Academy and the Scott Monument.

A scene from his play "The City of the Plague" was adapted by Alexander Pushkin as "A Feast in Time of Plague" and become a subject of a number of adaptations, including operas and a TV movie "Little Tragedies" (featuring Ivan Lapikov as The Priest).

Family

His brother James Wilson (1795–1856), was known as a zoologist.[7]

On 11 May 1811 Wilson married Jane Penny, the daughter of James Penny, a Liverpool merchant. She was described as "the leading belle of the lake country". They had five children, three daughters and two sons:

- Margaret Anne, married Professor James Frederick Ferrier[8]

- Mary, his biographer, married John Thomson Gordon FRSE (1813-1865), sheriff of Midlothian and son of Dr John Gordon[8][9]

- Jane Emily, married William Edmonstoune Aytoun[8]

- John, a clergyman of the Church of England

- Blair, for a time secretary to the University of Edinburgh[8]

He was cousin to Very Rev Matthew Leishman and they lived side by side during their childhood in Paisley.[10] Wilson was also the great great great uncle of Ludovic Kennedy.

Publications

Publications include the Works of John Wilson, edited by P. J. Ferrier (12 volumes, Edinburgh, 1855–59); the Noctes Ambrosianœ, edited by R. S. Mackenzie (five volumes, New York, 1854); a Memoir by his daughter, M. W. Gordon (two volumes, Edinburgh, 1862); and for a good estimate, G. Saintsbury, in Essays in English Literature (London, 1890); and C. T. Winchester, "John Wilson," in Group of English Essayists of the Early Nineteenth Century (New York, 1910).[4]

Notes

- Chisholm 1911, p. 694.

- Waterston & Shearer 2006, p. .

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- Gilman, Thurston & Colby 1905, p. 549.

- Garnett 1900, p. 109.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 694–695.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 694, fn. 1.

- Garnett 1900, p. 111.

- RSE 2006.

- https://archive.org/stream/matthewleishmano00leisuoft/matthewleishmano00leisuoft_djvu.txt

References

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). . New International Encyclopedia. 20 (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. p. 549.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Roy Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- Waterston, Charles D; Shearer, A Macmillan (July 2006). Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002: Biographical Index (PDF). II. The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 978-0-902198-84-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Garnett, Richard (1900). "Wilson, John (1785-1854)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 62. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 107–112.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Garnett, Richard (1900). "Wilson, John (1785-1854)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 62. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 107–112.  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wilson, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 694–695.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wilson, John". Encyclopædia Britannica. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 694–695.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Wilson (Scottish writer). |

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Wilson, John (poet)", A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature, 1910 – via Wikisource

- "Wilson, John". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- Bates, William (1883). . . Illustrated by Daniel Maclise (1 ed.). London: Chatto and Windus. pp. 58–63 – via Wikisource.

- Works by John Wilson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Wilson at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Christopher North at Internet Archive

- Works by John Wilson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Archival material at Leeds University Library