Joseph Jenckes Sr.

Joseph Jenckes Sr. (baptized August 26, 1599 – March 16, 1683), also spelled Jencks and Jenks, was a sword maker, blacksmith, mechanic, and inventor who was instrumental in establishing the Saugus Iron Works in Massachusetts Bay Colony where he was granted the first machine patent in America.

Joseph Jenckes Sr. | |

|---|---|

| Baptized | August 26, 1599 St. Ann Blackfriars, London, England |

| Died | March 16, 1683 (aged 83) |

| Occupation | Cutler, smithy, inventor |

| Known for | First machine patent in America |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Parents |

|

Jenckes was raised in a family of London cutlers and found employment west of London at a sword factory. After his wife and daughter died, and about the time the sword factory closed, he left his only surviving child with family and immigrated to New England.

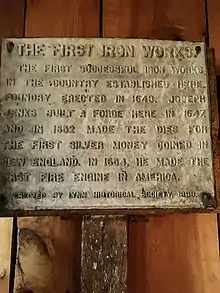

About 1645 he was working at the Saugus Iron Works near Lynn, Massachusetts. He is credited with making the first casting in America, inventing and manufacturing a new kind of scythe, and creating tools for the first American-made coins.

The son he left in England, Joseph Jenckes Jr., joined him at Saugus and later founded the town of Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Early life

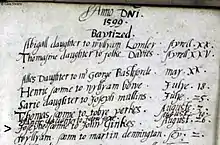

Joseph Jenckes was baptized on August 26, 1599, at St. Ann Blackfriars, London. His parents were John Jenckes Sr. (b. c. 1556) and Sarah Fulwater (b. 1573), both of St. Ann Blackfriars parish. He had an older sister, Sarah (b. 1597), and at least two older half brothers, John Jenckes Jr. (c. 1576–c. 1626) and Jonas Jenckes (c. 1580–1622). His patrilineal line has been traced to 15th-century Shropshire.[1][2]

Joseph Jenckes was raised in a family of cutlers and trade guild members. His father, John Jenckes Sr., and his half brothers, John and Jonas, were cutlers and members of the Worshipful Company of White Bakers, a London guild for bakers of light-grain bread. Jenckes's maternal grandfather, German immigrant Henry Fulwater (c. 1545–1603), was a cutler and a member of the Worshipful Company of Cutlers.[3]

London guilds—called livery companies—regulated trade in the city and provided apprenticeships. Membership conferred social status and city voting rights. Livery companies would accept new members by patrimony (inheritance) who no longer practiced their ancestors' trade, which is why some Jenckeses were members of a bakers' guild.[4][5]

In 1627, Joseph Jenckes married in Horton, Buckinghamshire, which is about 20 miles west of St. Ann Blackfriars, London.[6]

Sword cutler at Stone's factory

Between c. 1629 and c. 1641, Joseph Jenckes worked as a sword cutler at Benjamin Stone's sword factory at Hounslow, Middlesex, which is about 14 miles west of St. Ann Blackfriars.[7]

In 1629, Benjamin Stone, a member of the Company of Cutlers in London, converted a grain mill into a sword factory on the Cutt River in Hounslow Heath to meet the demand for military swords created by the ongoing Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). Stone employed English cutlers and German sword makers from Solingen. The swords were delivered primarily to the Tower of London's armory, with peak production between 1634 and 1637. By 1642, the First English Civil War had begun and Stone's sword factory was moved to Oxford.[7][8][9]

The Powysland Museum in Welshpool, Wales, has a sword in its collection made by Joseph Jenckes. The sword blade is inscribed with the words “JENCKES JOSEPH" on one side and "ME FECIT HOVNSLO” (Made in Hounslow) on the reverse.[1][10][11]

Immigration to New England

While in Hounslow, Joseph Jenckes became a widower in 1635 and one of his two children died in 1638. In 1639, he petitioned authorities to build a newly invented blade mill at Isleworth, however it is not known if he followed through with his plans. In c. 1641, Jenckes left his only child, Joseph, in England with family and immigrated to New England. In 1642, Jenckes was mentioned in New Hampshire records and, in 1643, he was mentioned in a deed for land near Kittery at the York River in Maine. He was working at the Saugus Iron Works near Lynn in Massachusetts Bay two years later.[12][13]

Blacksmith at the Saugus Iron Works

Association with the ironworks

By 1645,[lower-alpha 1] Joseph Jenckes was associated with the Hammersmith ironworks, later called the Saugus Iron Works. The Saugus Iron Works used the most advanced technology of the time and was the first successful integrated ironworks in America.[15]

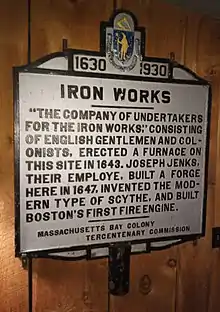

The business venture to build an integrated ironworks on the Saugus River began long before Jenckes arrived. In the late 1620s, bog iron ore was discovered in the Saugus River marshes near Lynn. In 1641, John Winthrop the Younger had samples of the ore shipped to England and soon afterwards an investment consortium headed by Winthrop called "The Company of Undertakers of the Iron Works in New England" invested in the proposed Saugus River project. In 1645, Winthrop resigned his position as company agent and was succeeded by Richard Leader. Leader chose the site and laid out the plan for the ironworks at the newly-formed company town called Hammersmith. The ironworks started operations in 1646 and, at its peak, engaged more than 200 workers.[16][17]

In 1647, Richard Leader gave permission to Jenckes to erect his foundry and forge along the tailrace (water channel) below the Saugus Iron Works blast furnace. In the mid-1650s, the Company of Undertakers entered bankruptcy and as part of the settlement much of the Saugus Iron Works—Jenckes's shop, the rolling mill, the slitting mill, and a corn mill—was awarded to a local businessman, Joseph Armitage. In 1656, Jenckes mortgaged his home and purchased these structures and the machines they contained. In 1678, the ironworks ceased producing iron, and in 1682 the dam was removed above Jenckes's shop. Jenckes died the following year.[18][19]

Archaeology at the Jenckes site

Between 1948 and 1953, archaeologist Roland W. Robbins excavated various sites at the Saugus Iron Works. In 1952, Robbins excavated what he called the "Jenks Site" where Jenckes built his foundry and forge on the tailrace. He uncovered a wrought-iron tuyere (bellows pipe), an anvil base, axes, chisels, knives, four water wheels, a water wheel hub and shaft, a cannonball, a sawmill saw blade, a scythe, hoes, spades, ox and horse shoes, and other objects. He discovered the "likely remains of Jenks' forge hearth" and he found the remains of a slitting mill and evidence of a wire-making operation.[20]

Career highlights

First machine patent in America

In 1646, Jenckes was granted the first machine patent in America.[21] He received a 14-year patent for a new kind of water-driven machine to make scythes, sawmill saw blades, and other edged tools. In his application to the Massachusetts General Court, he asked for “the usuall priveleg and liberty Granted by the high Court of Parliament in England to men that doe first sett upon workes of this nature”. He explained that he had “expended his estate, study, and labour, and have brought things to perfection; Another when he seeth it makes the like; and soe I loose the benefit of that I have studied for many yeeres before; which will tend to my Great damadg if not my utter undoeing”. The patent was issued by the General Court and bore the signatures of Governor John Winthrop and Deputy Edward Rawson.[22][23]

First casting in America

Jenckes made the first iron casting in America. The small pot with three legs, a lid, and bale (a handle) was presented by Jenckes to Samuel Hudson. Called the Saugus Pot, it is now displayed at the Saugus Public Library. Metallurgy tests confirmed that the pot matches metal fragments found at the site of the Jenckes forge.[24][25][26][27]

Scythe patent

In 1655, Jenckes was granted a 7-year patent for an improved scythe "for the more speedy cutting of grass". The European scythe had a straight snath (long wooden shaft) and the scythe blade was short and thick, which reduced its efficiency. The Jenckes scythe had a double-curved snath and the scythe blade was longer, thinner, and lightweight. The blade was strengthened by a chine (a rib) on back. The Jenckes scythe became known as the American scythe and it remains substantially unchanged today.[28][29][30][31]

Tools for the first coins in America (probable)

In 1652, John Hull and Robert Sanderson were appointed mint masters for Massachusetts Bay Colony. According to tradition, Jenckes cut dies for the first coins minted in America, such as the pine tree shilling. While there is no direct evidence for this claim, there is circumstantial evidence that Jenckes created steel punches, blank dies, and other tools for the Hull Mint.[32]

Jenckes had an early interest in coin making. In 1654, Jenckes wrote a letter to Edward Hull, John Hull's brother, about recruiting a die maker. In 1672, Jenckes petitioned the General Court to make coins; however, the court rejected Jenckes's request: "In ans to the humble proposal of Joseph Jenks, Sen. for ye making of money etc the Court judgeth to meet not to grant his request".[33] In the 1650s, Hammersmith had the only blast furnace hot enough to make steel or case hardened wrought iron punches, die blanks, crucibles, and other tools that Hull and Sanderson required.[32]

First fire engine in America (inconclusive)

Boston suffered a serious fire in 1653 and the following year the selectmen of Boston approved the purchase of fire engines from Joseph Jenckes: "The select men have power and liberty hereby to agree with Joseph Jynks for Ingins to Carry water in Case of fire, if they see Cause soe to doe". In 1702 the selectmen referred to an old engine in need of repairs which may have been the Jenckes engine. However, no document confirming that Jenckes made the engine has been found.[34]

The legend of Thomas Veale (folklore)

In 1658, according to popular legend,[lower-alpha 2] Captain Thomas Veale and three other pirates sailed up the Saugus River. The pirates visited the Saugus Iron Works at night and left a note on the door of Jenckes's forge requesting shackles. They hid in Lynn Forest at a place now called Pirates' Glen. The order was filled, but the shackles were used on three of the pirates. Veale escaped and buried treasure in a nearby cavern, now called Dungeon Rock, where he died during an earthquake.[24][35][36][37]

Family

Joseph Jenckes married Joan Hearne[lower-alpha 3] on November 5, 1627, at Horton, Buckinghamshire. Joan Hearne was born in c. 1607 in Horton and died on February 28, 1635 at Isleworth, Middlesex. They had two children: Elizabeth, b. c. 1630; and Joseph Jenckes Jr., b. 1628. His daughter, Elizabeth, died in 1638 in England and his son, Joseph, who remained in England when his father emigrated, joined him at the Saugus Iron Works in c. 1647.[39][40]

He married secondly Elizabeth in c. 1650 in New England. Elizabeth—whose maiden name and origin are unknown—was born in 1604 and died at Lynn in 1679. They had five children: Sarah, b. 1652; Samuel, b. 1654; Deborah, b. 1658; John, b. 1660; and Daniel, b. 1663.[41]

His son Joseph Jenckes Jr. would be a founder of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and his grandson, Joseph Jenckes 3rd, was the 19th governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.[42] A descendant was Nicholas Brown Jr., the philanthropist who gave his name to Brown University.[43]

Legacy

The Saugus Iron Works is considered the birthplace of the American iron and steel industry. Some products of Joseph Jenckes's forge, a copy of his patent, and two historical markers mentioning his accomplishments are displayed in the museum at the Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site in Lynn, Massachusetts.[20]

Notes

- In 1645, Jenckes owned a home about 3/4 of a mile southwest of the ironworks at School Street (now Main) and Vine Street in Hammersmith (now Saugus).[14]

- A version of the legend that mentions Jenckes is summarized in the International molders' and foundry workers' journal: "In 1647 Jenks built a forge in connection with his foundry business and it is on record that he made up an order for shackles for a gang of pirates who intended to use them in their trade, but the authorities used them on the gentlemen themselves".[24]

- Meridith B. Colket showed that early genealogies incorrectly identified Joseph Jenckes Sr.'s wife as Mary Tervyn and that, instead, she married another Joseph Jenckes in the same extended family.[38]

References

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 174.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 6, 12–23.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 12–23.

- Southwick 2001, p. 23.

- Browne & Colket 1956, p. 3.

- Browne & Colket 1956, p. 6.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 6–8.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, pp. 174–176.

- Southwick 2009, p. 31.

- Browne & Colket 1956, p. 8.

- Southwick 2009, p. 48.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 4, 9.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 176.

- Lewis & Eddy 1829.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, pp. 27, 119, 186.

- Browne 1952, p. xiii.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, pp. 30–34.

- Browne 1952, p. xviii.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, pp. 178–186.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, pp. 173–200.

- Brown 1994, p. 88.

- Fish 1909, pp. 313–314.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 178.

- Timer 1915, p. 968.

- Saugus Public Library.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 248.

- American Foundry Society.

- Dobyns 1994, p. 11.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 179.

- United States Agricultural Society 1858, p. 7.

- Browne 1952, pp. xvi–xvii.

- Jordan 2002, pp. 142–147.

- Browne 1952, pp. xvii, 571.

- Newhall, Newhall & Newhall 1897, pp. 158–159.

- Skinner 1896, p. 276.

- Lewis 1829, pp. 107–109.

- Marine Research Society 1837, pp. 254–256.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 5–6.

- Browne & Colket 1956, pp. 4, 6, 44.

- Griswold & Linebaugh 2010, p. 186.

- Browne 1952, p. 1.

- Browne & Colket 1956, p. 2.

- Colket 1956, p. 10.

Bibliography

- American Foundry Society. "About Metalcasting". www.afsinc.org. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- Brown, Travis (1994). Popular Patents: America's First Inventions from the Airplane to the Zipper. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781578860104.

- Browne, William Bradford (1952). Genealogy of the Jenks family of America. Concord, NH: Rumford Press.

- Browne, William Bradford; Colket, Meredith Bright (1956). The Jenks family of England; supplement, compiled under the terms of the will of Harlan W. Jenks, deceased. Boston Public Library.

- Colket, Meredith B. Jr. (1956). "The Jenks Family of England". New England Historical and Genealogical Register. 110: 9–20, 81–93, 161–172, 244–256.

- Dobyns, Kenneth W. (1994). The Patent Office pony: a history of the early Patent Office. Fredericksburg, VA: Sergeant Kirkland's Museum and Historical Society. ISBN 9780963213747.

- Fish, F. P. (1909). "The Patent System in its Relation to Industrial Development". Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. XXVIII (1): 313–339. doi:10.1109/T-AIEE.1909.4768169. ISSN 0096-3860. S2CID 51646472.

- Griswold, William A.; Linebaugh, Donald W. (2010). Saugus Iron Works: The Roland W. Robbins Excavations, 1948–1953 (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Jordan, Louis (2002). John Hull: the mint and the economics of Massachusetts coinage. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. ISBN 9781584652922.

- Lewis, Alonzo; Eddy, James (1829). Map of Lynn and Saugus : settled in 1629. Boston: Pendleton's Lithography.

- Lewis, Alonzo (1829). The history of Lynn. Boston: Press of J. H. Eastburn.

- Marine Research Society (1837). The Pirates Own Book, Or Authentic Narratives of the Lives, Exploits, and Executions of the Most Celebrated Sea Robbers. Sanborn & Carter.

- Newhall, James R; Newhall, Israel Augustus; Newhall, Howard Mudge (1897). History of Lynn, Essex county, Massachusetts: including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott, and Nahant. II. Lynn, MA: Nicholls Press. OCLC 17967166.

- Saugus Public Library. "Iron pot made at ironworks kept in Lynn Library". digitalheritage.noblenet.org. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- Skinner, Charles M. (1896). Myths and legends of our own land. 2. Philadelphia & London: J.P. Lippincott company.

- Southwick, Leslie (2001). London Silver-hilted Swords: Their Makers, Suppliers and Allied Traders, with Directory. Royal Armouries. ISBN 9780948092473.

- Southwick, Leslie (2009). "The London Cutler 'Benjamin Stone' and the Hounslow Sword and Blade Manufactories". Arms & Armour. 6 (1): 12–61. doi:10.1179/174962609X417518. S2CID 162347004.

- Timer, Present (1915). "Foundries of the Early American Days". International Molders' and Foundry Workers' Journal. 51: 967–968.

- United States Agricultural Society (1858). Field trial of reapers, mowers and harvest implements. Boston: Bazin. OCLC 15511268.

External links

- Mr. Jencks' Sword at drbenjaminchurchjr.blogspot.com

- Blacksmith shops at Saugus Iron Works: National Historic Site Massachusetts at nps.gov

- A Brief History of Dungeon Rock at flw.org

- Joseph Jenckes Sr. at Find a Grave

- Famous Kin of Joseph Jenckes at famouskin.com