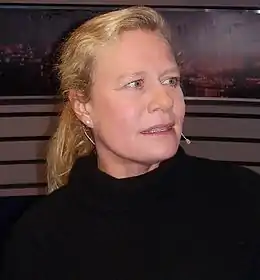

Kidnapping of Ulrika Bidegård

The kidnapping of Ulrika Bidegård, a member of the Swedish national show jumping team, took place on 20 January 1993 in front of her family's home in Sint-Genesius-Rode, Belgium. Cash withdrawals made with her credit card led the police to the kidnapper, a man living in a downtown Brussels apartment, where Bidegård was kept captive. The man was arrested, and his victim rescued, after over four days of a captivity that made headlines in both Sweden and Belgium.

Tried in 1995, the kidnapper was sentenced to fifteen years of penal labour. Lars Nilsson, a Swede in his thirties, had no prior convictions and was unanimously described by his family and friends as a kind and socially active person.

Background

Born on 9 September 1964,[nt 1] Ulrika Bidegård grew up in Onsala, outside Göteborg in Western Sweden.[1] She is the daughter of Kennet Bidegård, a well-off businessman,[sr 1] and of his wife Lena, a former Swedish Olympic gymnast.[sr 2] She started riding rather late in life, at the age of eleven, but quickly developed the skills of a champion.[1] At twenty-three, she moved to Belgium to train with "Brazilian wizard" Nelson Pessoa.[sr 3] Thanks to her resulting improvement, she was able to join the Swedish show jumping team. She took part in the European Show Jumping Championships and was to compete in the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, but eventually missed the competition after her horse Masada sustained an injury.[1]

Meanwhile, Bidegård's parents had joined her in Belgium in order to take advantage, as many Swedes did in the late 1980s, of the favourable tax laws.[sr 4] They settled in the "Swedish colony" of Sint-Genesius-Rode near Brussels where they bought a house. As they found the Belgian interior design style unappealing, and did not speak the local language, they had their new home renovated by a Swedish contractor. Ulrika then moved in with them.[sr 5]

Kidnapping

In the evening of Wednesday 20 January 1993, Ulrika Bidegård drove back home toward Sint-Genesius-Rode, after she spent the day training. Her parents were in Sweden, and the villa was empty.[sr 6] As she parked her car in front of the family house, a man wearing a mask showed up and threatened her with a firearm. Tied up and gagged, she was driven to her kidnapper's apartment in central Brussels. There she was placed in sitting position in a wooden box where she was kept during her whole captivity. Her kidnapper fed her sparingly and gave her water to drink laced with sedative.[1]

The man called Bidegård's father for the first time at his office in Göteborg. He demanded in English that neither the police nor the media be alerted, and did not talk of any ransom.[sr 7][sr 8] Kennet Bidegård immediately contacted a prosecutor, who alerted Interpol.[sr 9] When Bidegård's parents landed at Brussels airport, they were greeted by the Belgian police who had established a special task force.[sr 10] The story was quickly leaked to the press by an interpreter, and it made headlines in both Belgium and Sweden.[sr 11]

Because he had used a public phone booth to make calls to Sweden, the police knew that the kidnapper was located in downtown Brussels,[sr 12] but it was cash withdrawals made with Bidegård's credit card that led them to the man on Saturday 23 January. They followed him, and he led them to his apartment.[sr 13] As they did not know where Ulrika was located, at first they simply put the place under surveillance: an untimely arrest could set Bidegård's life at risk.[sr 14] Meanwhile, a photograph of the kidnapper was shown to Bidegård's parents, who immediately recognised him: he was Lars Nilsson,[2] a carpenter from Sweden, who had been part of the team that had worked on renovating the family house.[sr 15]

In spite of the constant surveillance of the kidnapper's apartment from a neighbouring building, the police were unable to determine whether Bidegård was held captive there.[sr 16] They finally decided to assault the apartment during the early hours of Monday, expecting to take the kidnapper by surprise. It was 2.30 am on the morning of 25 January when police forces stormed the apartment. Bidegård recovered her freedom after more than four days of captivity, and her kidnapper was arrested.[sr 17]

On Tuesday 26 January, a letter arrived at the Bidegård's home in Sint-Genesius-Rode. It enclosed a photograph of Ulrika, tied up in her wooden box, along with a laconic demand for ransom: "500000 USD WEDNESDAY". This letter had been posted by the kidnapper on the Friday night.[sr 18]

Trial

As the kidnapping took place in Brussels the inquiry was led by the Belgian police, but the Swedish police were asked to look into the background of the accused. When interrogated, relatives and friends depicted a kind, hard-working and socially healthy individual, with no predisposition to commit such a crime.[sr 19] For the Bidegård's themselves, the shock and consternation were enormous, as they had had excellent relations with the carpenter while he was working at their home.[sr 20]

The judicial inquiry concluded that the motive was purely financial: despite the quality of his work, the man was deeply in debt because of his bad debtors, and had been forced to pledge his parents' house. To get out of his predicament, he resorted to kidnapping the daughter of one of his rich clients.[sr 21]

The trial opened in Brussels on 2 May 1995.[sr 22] The accused kept a low profile, and apologised to the Bidegård family.[sr 23] On 10 May, he was sentenced to fifteen years of penal labour.[sr 24] He spent four years behind bars in Belgium before being transferred to Sweden, where he finished serving his sentence.[3] He was an exemplary inmate, and became a model of prisoner rehabilitation.[sr 25]

Epilogue

The kidnapping had both negative and positive impacts on Ulrika Bidegård's life. Unable to cope with the media pressure she put an end to her career as a top-level rider, although she remained active in the field. She became close to one of the Belgian policemen who had taken part in her release, and the two eventually married on 13 August 1994. The wedding was largely covered by the Swedish press. They have had two children.[1][sr 26]

In 2008, Ulrika Bidegård was back in Onsala, at the head of a riding school where she was training young riders.[1]

Notes

- Notes

- The date of birth comes from the Swedish Wikipedia.

P3 Documentary about Ulrika Bidegård

On 22 June 2013, the Swedish radio station P3 broadcast a documentary produced by Ida Lundqvist on the kidnapping of Ulrika Bidegård.

Notes

- 03:12 - 03:27 : Ulrikas pappa, Kennet...

- 05:50 - 06:01 : Ulrikas mamma, Lena...

- 04:04 - 04:29 : Ulrika är tjugotre...

- 05:14 - 05:49 : Vid den här tiden...

- 07:28 - 11:06 : Lena och Kennet köper...

- 12:48 - 13:41 : De första veckorna...

- 18:14 - 19:07 : Först ett halvt dygn...

- 22:46 - 23:01 : Mannen som ringer...

- 24:30 - 24:47 : Och då ringde vi...

- 25:17 - 26:51 : Samtalen flyger mellan...

- 29:32 - 31:52 : Polisen upprepar om...

- 38:36 - 39:00 : Det enda polisen vet...

- 45:01 - 46:38 : Men senare på lördagen...

- 49:28 - 50:24 : Men även om de har...

- 47:29 - 48:18 : Samtidigt som spanningspolis...

- 53:37 - 54:01 : Poliserna har installerat...

- 54:40 - 57:06 : Så då bestämde vi...

- 33:39 - 34:05 : Kidnapparen tar bilden...

- 64:48 - 66:26 : Nu är det upp till...

- 48:10 - 49:09 : Man blev ju klart chockad...

- 66:27 - 68:15 : ...var en jätteduktig snickare...

- 73:34 - 73:40 : Karl-Arne Ockell var...

- 75:11 - 75:20 : Jag vill be hela familjen...

- 77:10 - 77:46 : Den tionde maj 1995...

- 78:11 - 79:34 : Men man upptäckte...

- 72:17 - 72:36 : När vi gifte oss så...

References

- (in Swedish) Joakim Björck. Ibland påminns hon om dramat som kunde kostat henne livet Archived 2013-09-12 at the Wayback Machine. Helsingborgs Dagblad. 27 janvier 2008.

- Kidnapped show jumper is freed HeraldScotland 26 Jan 1993

- (in Swedish) Kjell Rynhag. Ulrika Bidegårds kidnappare får inte nåd. Aftonbladet. 12 mars 1998.