Larissa Cremaste

Larissa Cremaste (Ancient Greek: ἡ Κρεμαστὴ Λάρισα) was a town of Ancient Thessaly of less importance than Larissa in Pelasgiotis, and was situated in the district of Achaea Phthiotis, at the distance of 20 stadia from the Maliac Gulf, upon a height advancing in front of Mount Othrys.[1] It occupied the side of the hill, and was hence surnamed Cremaste, as "hanging" on the side of Mt. Othrys, to distinguish it from the more celebrated Larissa, situated in a plain. Strabo also describes it as well watered and producing vines. The same writer adds that it was surnamed Pelasgia as well as Cremaste.[2]

ἡ Κρεμαστὴ Λάρισα | |

The acropolis of Larissa Cremaste. | |

Shown within Greece | |

| Alternative name | Gardiki |

|---|---|

| Location | Pelasgia, Stylida |

| Region | Phthiotis, Greece |

| Coordinates | 38°57′42″N 22°50′28″E |

| Type | Ancient city |

| History | |

| Founded | Classical period |

| Abandoned | Frankish period |

| Cultures | Ancient Greece |

| Satellite of | Achaea Phthiotis |

History

From its being situated in the dominions of Achilles, some writers suppose that the Roman poets give this hero the surname of Larissaeus, but this epithet is perhaps used generally for Thessalian. Larissa Cremaste was occupied by Demetrius Poliorcetes in 302 BCE, when he was at war with Cassander.[3] It was taken by Lucius Apustius in the first war between the Romans and Philip V of Macedon, 200 BCE,[4] and again fell into the hands of the Romans in the war with Perseus of Macedon in 171 BCE.[5]

Archaeological remains

The ruins of the ancient city are situated upon a steep hill, 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from the modern town of Pelasgia, which was renamed to reflect the ancient surname.[6][7][8] The walls are very conspicuous on the western side of the hill, where several courses of masonry remain. William Gell says that there are the fragments of a Doric temple upon the acropolis, but of these William Martin Leake makes no mention.[9]

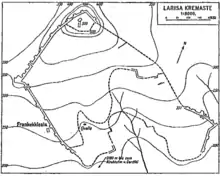

The only available plan of the ancient remains was made in 1912 by Friedrich Stählin, showing that a considerable city wall enclosed both the hilltop acropolis and a large section of the eastern slope of the hill. Stählin identified two larger gates in the lower fortifications and a postern in the outer wall of the acropolis. Much of the picture is reconstruction, such as the traces of a diateichisma dividing the settlement, with many segments of the wall apparently missing at the time of Stählin's visit. Stählin noted no remains predating the Classical period, with most of the standing ruins being Medieval (see below).[10]

No archaeological excavation or examination has been conducted of the ancient city since Stählin's visit, but a small late-Classical necropolis was discovered in 2006 just northeast of the acropolis.[11]

Harbour settlement at Agios Konstantinos

During rescue excavations prompted by the expansion of the national highway Lamia-Larisa in the early 2000s, considerable remains of an urban harbour settlement was found at the hill of Ayios Konstantinos, 4 km south of the ancient city, next the shore of the Maliac gulf.^a This settlement was probably the harbour of ancient Larissa, and situated in a protected bay of the Euboean Gulf, it must have been an important node in the local trade network. The remains have been dated to the Classical period, and appears to have been abandoned in the 4th century BC. It consists of a lower town at the beach protected by a fortification wall that extents to the adjacent hilltop where they enclose a small acropolis.[12] A Late Hellenistic to Roman cemetery later occupied the site, which appears to have been completely abandoned at this point.[13]

Medieval Gardikion

The site of ancient Larissa was abandoned after the Slavic invasions of the 7th century, to be reoccupied later in the Middle Ages. The new city went under the name of Gardikion (Ancient Greek: Γαρδίκιον) or Gardiki,[14] and soon an important local centre of commerce.

In the 11th century, Gardiki—referred to in Byzantine sources also as hetera Gardikia (Ancient Greek: ἑτέρα Γαρδικία), "the other Gardiki", to distinguish it from the town of the same name near Trikala—was an episcopal see (a suffragan see of the Metropolis of Larissa).[14] The Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela, who visited it in 1165, found it almost deserted, with only a few Greek and Jewish families resident.[14] Nevertheless, under Emperor Isaac II Angelos in 1189 it is listed as among the metropolitan sees, albeit without any suffragans.[14] A manuscript list indicates that there was a Greek bishop named John in 1191–92.[15]

In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, the town came under Frankish rule, and was known as Gardichy, Cardiche, Lacardica, and Gaudica.[14] The local see accordingly came under the Latin Church.[15] Gams[16] mentions five Latin bishops from 1208 to 1389, the first being Bartholomew, to whom many letters of Pope Innocent III are addressed;[15] Bartholomew was also bishop of Velestino and Demetrias,[14] and seems to have been the only residential Latin bishop.[17]

In 1222 it was recovered by the Epirote Greeks and the see was restored to its Greek Orthodox clergy, becoming an archbishopric and eventually again a metropolis.[14] In 1275 it was ceded by the ruler of Thessaly, John I Doukas, along with Zetounion, Gravia, and Siderokastron, to the Duchy of Athens as part of the dowry of his daughter Helena Angelina Komnene.[18][19] In ca. 1294 the town was granted by the Duke of Athens Guy II de la Roche to Boniface of Verona, who held its lordship at least until the Battle of Halmyros in 1311.[14]

Along with other towns in southern Thessaly such as Thaumakoi and Pharsalus, in the mid-1320s Gardiki came briefly under the rule of the Catalan Company, which had taken over the Duchy of Athens in the aftermath of Halmyros.[14][20] Latin bishops of the Dioecesis Cardicensis are still mentioned in 1363 and ca. 1396.[14] The town surrendered to the Ottoman Turks after the fall of Euboea in 1470, and its inhabitants were deported to Constantinople.[14]

The diocese is today listed by the Roman Catholic Church as a titular see.[21]

The visible ruins of the Classical-Hellenistic period are partially covered by the masonry of this later city. The most well-preserved part of the Medieval city is the hill-top keep which had been constructed on top of the previous acropolis, with a large cistern at its centre. The ruins of a church, the co-called Frangoekklisia (the "Frankish church") was visible immediately west of the ancient city wall by the early 20th century,[10] but nothing of it remains today. Most of the visible remains on the site are now quite overgrown with pournaria, making it hard to discern most of the antiquities.

An early Christian basilica, Ayia Dynamis, with preserved mosaics was uncovered in 1981 about 5 km to the south close to the harbour settlement of ancient Larissa.[22]

Modern situation

The site of ancient Larissa Cremaste is easily accessible for visitors, with signs directing from the national highway through the nearby village of Pelasgia. The hill-sides, however, are quite steep and covered in prickly shrubs, making the acropolis more difficult to reach.

References

- Strabo. Geographica. ix. p.435. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Strabo. Geographica. ix. p.440. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). 20.110.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 31.46.

- Livy. Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). 42.56, 57.

-

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Larissa". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Larissa". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray. - Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 55, and directory notes accompanying.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- Gell, Itinerary of Greece, p. 252; Leake, Northern Greece, vol. iv. p. 347.

- Stählin, Friedrich (1924). Das hellenische Thessalien: Landeskundliche und geschichtliche Beschreibung Thessaliens in der Hellenistischen und römischen Zeit. Stuttgart.

- "Αρχαιολογικές ανασκαφές στο Κάστρο". Πελασγία. Vassilis Axelis. 2006. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- Stamoudi, Ekaterini (2008). "Η έκφραση της Κλασικής πόλης στη Θεσσαλία. Το παράδειγμα της Πελασγίας". 1ο Διεθνές Συνέδριο Ιστορίας και Πολιτισμού της Θεσσαλίας: πρακτικά, 9-11 Νοεμβρίου 2006, Λάρισα. Larisa: Περιφέρεια Θεσσαλίας. pp. 139–151.

- Papastamatopoulou, Aristea (2019). "Ένας υστερορρωμαϊκός καμαροσκεπής τάφος σε μια άγνωστη κλασική πόλη της Αχαΐας Φθιώτιδας" (PDF). Themes in Archaeology. 3 (3): 368–379. Retrieved 2021-01-08.

- Koder & Hild 1976, p. 161.

- Sophrone Pétridès, "Cardica" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1908)

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 432

- Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, pp. 166–167; vol. 3, p. 153; vol. 4, p. 135; vol. 5, p. 143

- Koder & Hild 1976, pp. 72, 161.

- Fine 1994, p. 188.

- Fine 1994, p. 243.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", p. 858

- Papageorgiou, Panagiota (2015). Η παλαιοχριστιανική βασιλική της θέσης «Αγία Δύναμις» στην Πελασγία Φθιώτιδας. Volos.

Notes

- ^a Still visible today immediately north of the road-side (38.92522262655854°N 22.852694134930132°E).