Latif al-Ani

Latif al-Ani (born 1932 in Baghdad, Iraq) is an Iraqi photographer, often known as "the father of Iraqi photography" and noted for his photographic works that combine both ancient and modern themes. During his active career from the 1950s through to the late-1970s, he chronicled an Iraq way of life that was rapidly being lost as the country embarked on a modernisation program. He documented people, ancient monuments and many facets of urban life in Iraq. He stopped taking photographs following the rise of Saddam Hussein, finding that he was unable to maintain his former optimistic outlook for Iraq's future.

Latif al-Ani | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1932 Baghdad |

| Nationality | Iraqi |

| Known for | Photographer |

Life and career

Latif al-Ani was born in Baghdad in 1932.[1] During his childhood, relatively few commercial photographers were operating in Iraq. The social and religious prohibitions on making images and figurative representations meant that Iraq was relatively late-adopter of photography and cinematography. A handful of photographers and film-makers, such as Abdul-Karim Tiouti and Murad al-Daghistani, had been operating in Basra and Mosul since the late 19th-century and the early 20th-century, but opportunities for young Iraqis to learn the art of photography were rare.[2] It was not until the late 1940s, when Al-Ani was an adolescent that the number of commercial photographic studios in Iraq's major cities, including Baghdad, proliferated.[3]

Al-Ani was first exposed to photography when, as a boy, he would help in his older brother's Mutanabbi Street shop which was adjacent to the studio of a Jewish photographer, by the name of Nissan. The young Al-Ani was fascinated. Noting the boy's interest, Al Ani's brother bought him a camera, a Kodak box, in around 1947, when al-Ani was 15 years. After that, the camera never left his side.[4] His earliest photos were of the everyday scenes and objects in his immediate surroundings- street life, palms, plants, faces and people on rooftops. This type of subject matter would become a recurring theme in his work.

In the 1950s, he seized the opportunity to embark on a career in photography. A friend of al-Ani's, Aziz Ajam, was working as an editor for the Iraqi Petroleum Company's in-house magazine. Al-Ani applied for a traineeship there, and in 1954, he began working under the direction of Jack Percival, and effectively became his apprentice. While at IPC, al-Ani learned all aspects of photography, including aerial work.[5] As a staff member of the IPC, he took photographs for the company’s Arabic-language magazine, Ahl al-Naf [People of Oil] under Percival's watchful eye.[6]

In 1960, he founded the Photography Department at the Ministry of Information (subsequently renamed Ministry of Culture). At the time, he was one of the very few people in Iraq who knew how to develop colour photographs.[7] He hired an assistant, Halim al-Khatat, who later became a well-known photographer.[8] His department published the magazine, New Iraq, (in five languages: Arabic, Kurdish, English, French and German) which was distributed to foreign diplomatic communities and international organisations operating in Iraq.[9] During this period, Al-Ani travelled extensively documenting Iraqi social life and culture, industry, agriculture, workers, machinery and development. This type of work was not only a good fit with Al-Ani's own preoccupations, but also fitted with the government’s socialist agenda. Al-Ani explains his motivations:

"It started with the revolution of 1958. This past is being deleted; it has been deleted. I felt there would be no stability. Men were eaten up and newcomers came. Pandora’s box was opened and ignorant people came to rule, who had no culture or understanding of the power they held. Fear was a major motive to document everything as it was. I did all that I could to document, to safeguard that time." [10]

For his role in chronicling the so-called golden age of Iraq, al-Ani has been labelled as the "father of Iraqi photography".[11]

In the 1970s, he was appointed as the Head of photography at the Iraqi News Agency.[12] This provided further opportunities to document the social and cultural life of Iraq. Throughout his career, he felt compelled to record a way of life that he feared was being lost as the country embarked on a period of 'modernisation'. Al-Ani was an optimist and “wanted to show Iraq as a civilised, modern place." At the same time, he was proud of Iraq's ancient Sumerian and Mesopotamian past.[13]

Al-Ani had an instinct for juxtaposing the layers of Iraq's ancient art heritage with distinctly modern themes. His work has been influenced by mid-20th century Iraqi artists, including Jawad Saleem.[14] For example, his portrait of the US Couple in Ctesiphon shows an American couple visiting the Taq Kisra (arch at Ctesiphon) in the background, while they listen to an elderly Bedouin man seated on the ground playing the rabab.[15]

In the 1960s and 70s he enjoyed international success, working and exhibiting in the Middle East, Europe and the United States. However, he stopped taking photographs in 1979 when Saddam Hussein's regime placed a ban on taking photographs in public. Not only was it dangerous to take photographs in public, but al-Ani had lost his optimistic outlook for Iraq's future.[16]

After his retirement, al-Ani's work was virtually forgotten for some 40 years.[17] Al-Ani recalled stopping at a news kiosk in 2005 where they were giving away free calendars - and upon inspection, he realised that more than half of the photographs were his own work, but had been reproduced without any attribution since no-one knew who the photographer was.[18] His contribution to Iraqi art and culture was 'rediscovered' by a team from the Ruya Foundation, who were working to preserve Iraq's artistic heritage and came across al-Ani's collection.[19] In late 2017, they mounted a solo exhibition of Al-Ani's work at Coningsby Gallery in London. This event, combined with the publication of a monograph about the artist, has stirred considerable interest in the photographer and his work.[20]

Work

The majority of his photographs are in black and white. His ability to combine Iraq's ancient art heritage within a contemporary format suggests that he was influenced by mid-20th century Iraqi artists, including Jawad Saleem.[21]

As with many Iraqi artists, much of his archive was destroyed or looted during the US invasion of Iraq of 2003.[22] The archive of Arab Image Foundation has several hundred surviving al-Ani photographs.[23]

Select list of published photographs

- Lady in the Eastern Desert

- US Couple in Ctesiphon

- Haidar-Khana Mosque, Rashid Street, Baghdad

- Building the Darbandikhan Dam

- Al Malak, Baghdad

- Architecture in Baghdad, Bab Al Muadham

Al-Aqida secondary school, Bagdad, 1961

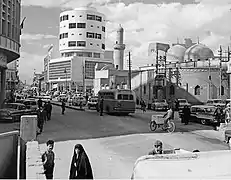

Al-Aqida secondary school, Bagdad, 1961 Al-Rasheed Street 1961

Al-Rasheed Street 1961 Babylon, Iraq, 1970

Babylon, Iraq, 1970 Coppersmith at Suq Al-Safafir, Baghdad, 1962

Coppersmith at Suq Al-Safafir, Baghdad, 1962 Liberty Monument and Umma Park, Baghdad, 1961

Liberty Monument and Umma Park, Baghdad, 1961 Liberty Monument, Baghdad, early 1960s

Liberty Monument, Baghdad, early 1960s Malwiya, Samarra, 1960

Malwiya, Samarra, 1960 Model, Baghdad, 1956

Model, Baghdad, 1956 Murjan Mosque, Baghdad, 1962

Murjan Mosque, Baghdad, 1962 Taq-i Kisra, Baghdad, 1963

Taq-i Kisra, Baghdad, 1963 Traditional market, Baghdad, 1961

Traditional market, Baghdad, 1961

Legacy

He is the subject of two books:

External links

- Arab Image Foundation - digital resource, currently digitising hundreds of photographs made by Latif al-Ani and other Arab photographers]

- http://www.iraqsinvisiblebeauty.com/ - documentary about the life and work of Latif Al Ani

References

- Some sources state that he was born in Karbala; See for example, M. Gronlund's "How Latif Al Ani captured Iraq’s golden era through a lens" in The National 6 May 2018, Online:, but all sources appear to agree that he grew up in Baghdad

- Kalash, K., "In Digital Technology, Solar Photography is a Time-immemorial Profession, " Iraq Journal, Online:

- "The First Photographers", Iraq National Library and Archives, Online: (translated from Arabic)

- Ruya Foundation, From the air, I saw things in a different way: photographer Latif al Ani reflects on his life and work, May 1, 2015

- Leech, N., "Latif Al Ani: chronicler of modernity in a now vanished Iraq", The National 11 July 2017 Online:

- Leech, N., "Latif Al Ani: Chronicler of Modernity in a now vanished Iraq", The National 11 July 2017 Online:; Gray, L.A., "Through the Lens 1953–1979: Latif al-Ani", Art Asia Pacific July–August, 2018 Online:

- Holledge, E., "Capturing the Social Fabric" Gulf News, 13 December 2017 Online:

- Hatje Cantz (publisher), "Interview with Latif al-Ani" 2017, Online:

- Pelletier, M., "Images of a Vanished World", Apollo Magazine 7 December 2017 Online:

- Hatje Cantz (publisher), "Interview with Latif al-Ani" 2017, Online:

- Holledge, E., "Capturing the Social Fabric" Gulf News, 13 December 2017 Online:; Pelletier, M., "Images of a Vanished World", Apollo Magazine, 7 December 2017 Online:

- Waters, L., "Happy Tourists, Hula Hoops, Architectural Wonders: Iraq a You've Never Seen", The Telegraph (UK), 7 December 2017, Online:

- Smyth, D., "The founding father of Iraqi photography gets his first London show", British Journal of Photography, 16 November 2017 Online:

- Wullschlager. J., "Latif Al Ani and Iraq’s Golden Age", Financial Times, (UK) 2 December 2017 Online:

- Leech, N., "Latif Al Ani: Chronicler of Modernity in a Now Vanished Iraq", The National 11 July 2017 Online:; David, C., "With or Without Consent: Latif al-Ani's Iraq", Al Nafas Magazine,February, 2016, Online:

- "Latif al-Ani:Interview", Studio International 1 May 2018 Online:; "Driven underground by Saddam, 'Iraq's greatest photographer' Latif Al Ani is honored at last", CNN News, 17 November 2018 Online:

- Arango, T., "Picturing Iraq in a Bygone Era", New York Times, Online:

- Holledge, E., "Capturing the Social Fabric" Gulf News, 13 December 2017 Online:

- Arab British Centre, "The Ruya Foundation Presents Latif al-Ani" Online:

- Pelletier, M., "Images of a Vanished World", Apollo Magazine 7 December 2017 Online:

- Wullschlager. J., "Latif Al Ani and Iraq’s Golden Age", Financial Times, (UK) 2 December 2017 Online:

- Smyth, D., "The founding father of Iraqi photography gets his first London show", British Journal of Photography, 16 November 2017 Online:

- The FAI is currently digitising photographs for its collection. See: FAI Projects Archived 2018-08-31 at the Wayback Machine

- This book was the winner of the Historical Book Prize for 2017 at Les Rencontres d’Arles