Laura Papo Bohoreta

Laura Papo Bohoreta (born: Luna Levi) (March 15, 1891 – 1942) was a Bosnian Jewish feminist, writer, and translator who devoted her research to the Sephardic condition of women in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[1][2] She is considered the first Sephardic Jewish and Balkan feminist.

Biography

Family and early life

Laura Papo Bohoreta was born in Sarajevo on 15 March 1891 into the poor Jewish family of Juda and Esther Levi. She was the first of the couple's seven children. Juda Levi was a trader, but as he did not have success in Sarajevo, he relocated his family to Istanbul in 1900. Originally named Luna, they changed her name once arriving in Turkey into a more modern and international one - Laura. Laura attended the International French School for Jews "Alliance Israélite Française" in Istanbul for eight years. After eight years, Levi's family returned to Sarajevo, just as poor as before, only with more children. To help her family, Laura gave lessons in French, Latin, German as well as piano lessons. With Laura's help, her sisters Nina, Klara, and Blanka (the mother of the famous writer Gordana Kuić) opened a salon "Chapeau Chic Parisien" in Sarajevo. Immediately upon returning to Sarajevo, at the age of 17, Laura realized that the fire of the Sephardi tradition and folklore had begun to extinguish, and she began collecting romances, poems, stories, and Sephardic proverbs. In addition to this, she translated and adapted the works of French authors: Jules Verne "Captain Grant's Children" and Emile de Girardin's "Joy of Fears" ("La joie fait peur – Alegria espanta").[2]

"Die Spanolische" (1916)

A milestone in her social engagement was the article "South Slav women in politics" ("Die Südslawische Frau in der Politik"), published in 1916 in the "Bosnische Post", a Bosnian-Herzegovinian newspapers printed in German, where Jelica Belović-Bernadzikowska dedicated a chapter to Sephardic women in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In this article, the Sephardic woman was described as a nun, a tradition of a loyal woman who faithfully preserves patriarchal values. This angered Laura, and she published the answer "Die Spanolische" the same day a week later in the same newspaper, with the intention of a more realistic presentation of the Sephardic woman, her role in the family, her virtues and defects.

Marriage and family issues

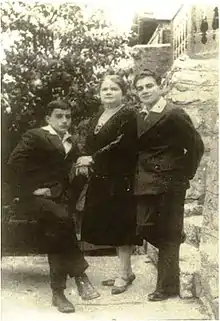

That same year, Laura married Daniel Papo. In 1918, their first son, Leon, was born, and a year later Bar-Kohbu, Kokija. Unfortunately, the marriage of Laura and Daniel did not last long after Daniel suffered from severe mental disorders (most likely from PTSD as he had participated as a soldier in the First World War) and was permanently placed in a psychiatric institution. Laura, at age 28, remained completely alone with two young children. For the next few years, she was not socially engaged, spending her time earning a living and taking care of her sons. In the Great Crisis, Laura thought of her family, her children, helping her sisters, mother, and father.

After accommodating her husband to a psychiatric institution, she did not lose her faith in life. She worked, wrote, collected folklore material, supported the women, and motivated them to be wives, have children, respect the customs of their mothers and grandmothers, but at the same time be aware of the age in which they live and adapt to it. Laura was not a feminist in terms of equal rights of men and women but in terms of awakening a woman's awareness of the power she possesses and which she has to endure and persevere in achieving all her goals, to be interested in art, reading, writing and developing her personality. Laura believed that the development of women should not depend on the environment, but on themselves, on their desire to progress.[2]

In 1919, Papo wrote a sketch called "Preparations for Passover" and presented it with her sisters on the evening of the Jewish community of Wesko. Following the success of the performance, the representatives of the La Benevolencija Association of the Sarajevo community appealed to Papo to write a skit for an evening organized by the association. Thus began her theatrical career among the Jewish community in Sarajevo.

"Madras" (1924)

Laura came back to social engagement in 1924 in response to the nostalgic story of Avram Romano Buki's "The Two Neighbors in the Courtyard" ("Dos vizinas in el cortijo"), published in the journal Jevrejski život (Jewish Life). Avram Romano Buki had invented the story of a conversation between two neighbors, Lea and Bohoreta. Neighbors talk casually about everyday events, acquaintances, and friends. Laura was especially angry that one of the neighbors, Lea, claimed that schools were ruining young women, because they want to educate themselves and no longer want to iron, to cook, to wash clothes, to sew, nor to tingle their husbands.

In the next issue of the same magazine, Laura published the article "Mothers" ("Madras") and signed it with the pseudonym Bohoreta. In this article, she sharply criticised Buki and his conservatism. She wrote for the first time in the Jewish-Spanish language (Ladino). According to Eliezer Papo, she chose the pseudonym of Bohoreta to identify the readers with the person described in Buki's story. To the ideas expressed in the article "Mothers" she remained faithful throughout her lives and in all their literary and dramatic work: that women must be educated, and not deal only with housework, because they have to adapt to the current and future situation in which a woman will have to work to survive. Laura knew very well what she was talking about because she was able to raise her sons alone thanks to her education.[2]

Later, she published in the same newspaper the novel Morena ("Brunette").

"La mužer sefardi de Bosna" (1931) and other dramas of the 1930s

In 1931, upon the encouragement of Vite Kajon, a great Yugoslav and Sarajevo intellectual writer, she writes the monograph "The Sephardic Woman in Bosnia" (La mužer sefardi de Bosna), based on the 1916 article by Bernadzikowska-Belovic, later translated into Bosnian by Muhamed Nezirovic ("Sefardska žena u Bosni"). In her book, Laura described in detail the customs, the way of dressing, cooking, virtue, and the defect of the Sephardic woman, emphasizing traditional values that should not be forgotten, but at the same time encouraging women to adapt to the current situation and to accept the demands placed on them by modern times.

During the 1930s, Laura wrote seven drama: the single-act "Sometimes" (Avia de ser), "Patience of the Couples Worth" (La pasjensija vale mučo), "Past times" (Tjempos pasados), the drama in three acts "My Eyes" (Ožos mios), and three drama of social content in three acts "The Mother and the Blind of Good" (Esterka, Shuegra ni de baro buena) and "The Brotherhood of the stepmother, the name speaks enough "(Hermandat Madrasta el nombre le abasta).

Laura Papo wrote in Ladino at a time when there was a significant decrease in the use of such language. She renewed and adapted expressions to the spirit of the time and succeeded in her writings to instill the connection between the young people of the community and the language in which their forefathers spoke. Papo collaborated with the youth theater group of the Sarajevo community Matathias, which performed her plays. In this, she argued, she was struggling with "linguistic assimilation." Her writings were written in three spelling methods. In general, her publications, articles, and plays for the local audience were in Serbo-Croatian with elements of Castilian, which helped to spread her works. In her writings not to the general public, she writes mixedly in Castilian and Serbo-Croatian, and in her formal writings that are not for the local audience, she emphasizes Castilian.[3]

She intended to teach women through familiar and frequent situations in each family, how to live, how to overcome current problems, and meet the needs of both the family and society. Every woman can be a mother and work outside the home, without the bother of conscience, while respecting the Sephardic tradition. It should be kept in mind the fact that Laura lived in the Balkans, in the period before, during, and after the First World War, and between the two wars, during the Great Economic Crisis and the fascist persecution of the Jews.[2]

World war two and death

At the very beginning of the Second World War and the Holocaust, in 1941, both her sons were taken by the Ustasha to the concentration camp Jasenovac. Broken with sorrow and worry, Laura fell ill and died in 1942 at the Sisters of Mercy Hospital in Sarajevo. She did not know that her sons had been killed by the Ustasha on the way to Jasenovac.[1][2]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laura Papo. |

- The Scent of Rain in the Balkans, novel by her niece Gordana Kuić dedicated to Laura Papo's history

- History of the Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina

References

- Laura Papo Bohoreta (1891. – 1942.) Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Rikica Ovadija, Behar,12. 3. 2014

- Laura Papo Bohoreta – prva sefardska feministkinja, Jagoda Večerina, Autograf, 22. 10. 2013

- אליעזר פאפו, משנתה הלשונית של לאורה פאפו, בוכוריטה, בהקשרה ההיסטורי והחברתי, פעמים, גיליון 118, עמודים 123–173, באתר יד בן צבי. PDF