Lay-Up process

A Lay-Up process is a moulding process for composite materials, in which the final product is obtained by overlapping a specific number of different layers, usually made of continuous polymeric or ceramic fibres and a thermoset polymeric liquid matrix. It can be divided into Dry Lay-up and Wet Lay-Up, depending on whether the layers are pre-impregnated or not.

Dry Lay-up is a common process in the aerospace industry, due to the possibility of obtaining complex shapes with good mechanical properties, characteristics required in this field. On the contrary, as Wet Lay-Up does not allow uni-directional fabrics, which have better mechanical properties, it is mainly adopted for all the other areas, which in general have lower requirements in terms of performances.[1][2]

The main stages of the Lay-Up process are the cutting, the lamination and the polymerization. Even if some of the production steps can be automatised, this process is mainly manual (hence often referred to as the Hand Lay-Up process), leading to laminates with high production costs and low production rates with respect to the other techniques. Hence, nowadays, it is mainly suitable for small series productions of 10 to 1000 parts.[2][3]

Cutting

Cutting fabrics is the first stage of the Lay-Up process. Even though the fibres, in general, have high tensile strength, the shear strength is usually quite low, so it is fairly easy to cut. This process can be manual, semi-automatic or completely automatic.[1]

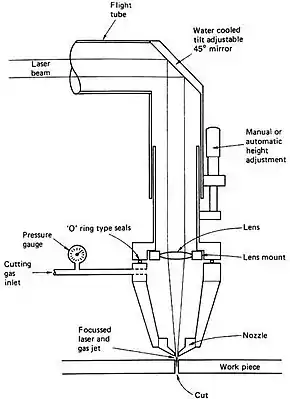

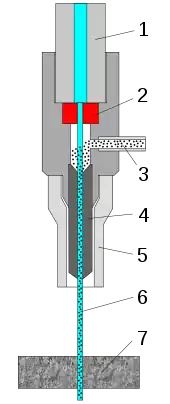

For what concerns the tools, the most common are scissors, cutters, knives and saws. More automatized alternatives are the die-cutting systems, which allow reaching higher production rates and maintaining contained costs, as they allow to cut more layers of fabric at the same time. These methods require different skills from the operator and provide different finish precisions, but they all are mechanical procedures and have a major disadvantage in common: the physical contact between the cutting tool and the fibres.[4] An alternative with less friction is the ultrasound method, which consists of cutting the fabrics with a blade solicited with high-frequency mechanical vibrations, produced by an internal source integrated into the system.[1] There are also completely contact-free cutting techniques, like laser cutting and water jet cutting, both usually embedded on CNC machines. The first is obtained through a convergent radiation beam which vaporizes the material underneath and pressurized gas to remove the volatile particles and the melted material. The second is based on a high-pressure liquid beam which reaches a velocity of 2.5 times the speed of sound, creating a pressure on the fabric which is higher than the compression resistance of the material and resulting in a net cut. Both these methods have a disadvantage which needs to be considered before choosing the cutting methods: the beams create high-temperature areas along the cut axes, in which the physical characteristics of the material can be altered significantly.[1][5]

During the cutting process, a fundamental parameter to be considered is the nesting layout, as to say the arrangement of the different shapes to be cut in the fabric in order to reduce the scraps. The patterns are generally created digitally and, when possible, given to a CNC machine or, otherwise, replicated by hand.[1]

Lamination

Lamination of the fabrics is the second stage of the Lay-Up process. It is the procedure of overlapping all the layers in the correct order and with the correct orientation. In the case of Wet Lay-Up, the preparation of the resin is included in this operation, as the fabrics are not already impregnated. Lamination is usually performed in a clean-room to avoid particles inclusions within the layers, which would interfere with the final product characteristics.[1]

The most important tool is the mould, which can be male or female depending on the application. It can be made of different materials, depending on the shrinkage and the thermal expansion coefficient of the composite material, the stiffness required, the surface finish needed, the draft angles and the bending angle. Furthermore, the mould needs to be stable at the lamination temperature, bear the operative pressure, be resistant to wear, be compatible with the other tools used, be resistant to washing solvents and it must be easy to apply release agents.[6]

The first step of lamination is to apply a release agent on the mould, fundamental to avoid adhesion between the resin and the mould itself. If needed for surface finish, a layer of peel-ply could be added. Peel-plies are nylon films used to obtain a specific roughness of the surface on which they are applied, to protect them during storage and to trap volatile particles during polymerization. Then, all the fabric layers are overlapped following the instructions on the ply-book, which contains a list of all the operations to be performed during this process. Usually, intermediate compacting are made every 4 or 5 layers, in order to let the air evacuate and to obtain a final product with higher mechanical characteristics.[1]

After all the fabrics have been put in the right position, another layer of peel-ply is applied on top, with the same purpose as the first one. A sequence of other layers is added above it: the release film, which separates the laminate from the other layers but still allows the excess resin to pass through; the bleeder, whose main function is to absorb the excess resin; a barrier, to separate the bleeder from the breather; the breather, to distribute the vacuum homogeneously among the external surfaces and to avoid the folds of the vacuum bag to be transferred to the laminate; the vacuum bag, a flexible polymeric film, typically made of nylon, able to maintain the vacuum created with a vacuum pump. Further important elements are the valves and the sealant used to hermetically seal the bag.[1][7][8][9]

This process can be manual, semi-automatic or completely automatic. When done entirely by hand, lamination is a long and difficult process (due to the strict tolerances required). An alternative is a semi-automatic - also called "mechanically assisted" - process, constituted of a machine which handles the layers, then applied on the mould by an operator. It is completely automatic if a machine, like the automatic tape laying machine, can also place the layers in the right position and orientation. These automatic methods allow reaching a high production rate.[1]

Polymerization

Polymerization of the laminate is the third and final stage of the Lay-Up process. This phase is of utmost importance to obtain the required characteristics of the final product.[1]

Polymerization in autoclave and industrial oven

This process can be done at room temperature with just a vacuum pump, to control vacuum, with the aid of an industrial oven connected to a vacuum pump, to control temperature and vacuum, or with an autoclave, to control temperature, vacuum and also hydrostatic pressure.[1][10]

Polymerization in the autoclave is a technique which allows obtaining laminates with the best mechanical properties, but it is the most expensive and it permits the use of open moulds only. The advantage is due to the fact that the pressure helps to bond the composite layers and to exhaust air inclusions and volatile products, increasing the quality of the process.[8][11] Each combination of fabric and resin has its own optimal polymerization cycles, dependent on fibres wettability and resin properties, like viscosity and gel point. Typically, the three cycles of temperature, pressure and vacuum are experimentally studied to obtain the best combination of the three parameters. Polymerization in the industrial oven is similar but without pressure control. It is less expensive and therefore used for all those laminates which do not need to have very high mechanical properties. Moreover, as industrial ovens, in general, are bigger than autoclaves, they are used for all those components with non-standard dimensions.[1]

Polymerization with matched-die moulding

Polymerization with matched-die moulding is used for plane or simple-geometry laminates and can include a vacuum pump and an electric or hydraulic heat source. It is made of a press with male and female moulds that close to form a gap with the shape of the component, the width of which is regulated to control the thickness of the part. The press can not apply a hydrostatic pressure as the autoclave, but only a vertical one. Matched-die moulding allows to have a very high dimensional control, a good surface finish on both surfaces, and reasonable production rates but, in return, it can have fibres misalignment and it is very expensive.[1][8][12]

Problems

As Meola et al. pointed out in Infrared thermography in the evaluation of aerospace composite materials, "Several different types of defects may occur during the fabrication of composites, the most common being fibre/play misalignment, broken fibres, resin cracks or transversal ply cracks, voids, porosity, slag inclusions, nonuniform fibre/resin volume ratio, disbonded interlaminar regions, kissing bonds, incorrect cure and mechanical damage around machined holes and/or cuts." [13]

Also, three main problems related to cutting polymerized composite materials must be considered. The first is that reinforcement fibers are abrasive, hence traditional tools for cutting are not suitable, as their lives would be very short and their blunt edges would damage the materials. The second is that composite materials are not conductive, and this can cause heat accumulations and deformations. The last is that composite materials tend to delaminate when cut, therefore it is necessary to take that into account when choosing the cutting method.[14][15]

References

- Sala, Giuseppe; Di Landro, Luca; Airoldi, Alessandro; Bettini, Paolo (2015). Tecnologie e Materiali Aerospaziali (1st ed.). Politecnico di Milano. pp. 1-24 (Chapter 37).

- Callister Jr, William D.; Retwisch, David G. Materials Science and Engineering: an introduction (8th ed.). Wiley. pp. 626-667 (Chapter 16). ISBN 978-0-470-41997-7.

- Swift, K. G.; Booker, J. D. Manufacturing Process Selection Handbook. p. 165.

- Fuchs, A.N.; Schoeberl, M.; Tremmer, J.; Zaeh, M.F. (2013). "Laser Cutting of Carbon Fiber Fabrics". Physics Procedia. 41: 372–380. Bibcode:2013PhPro..41..372F. doi:10.1016/j.phpro.2013.03.090.

- Masoud, Fathi; Sapuan, S.M.; Mohd Ariffin, Mohd Khairol Anuar; Nukman, Y.; Bayraktar, Emin (2020). "Cutting Processes of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites". Polymers. 12 (6): 4. doi:10.3390/polym12061332. PMC 7361972. PMID 32545334.

- Sala, Giuseppe; Di Landro, Luca; Airoldi, Alessandro; Bettini, Paolo (2015). Tecnologie e Materiali Aerospaziali (1st ed.). Politecnico di Milano. pp. 1-24 (Chapter 42).

- "What is Vacuum Bagging?". Coventive Composites. 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- Eckold, Geoff (15 January 1994). Design and manufacture of composite structures. Woodhead Publishing Limited. pp. 273–277. ISBN 1-85573-051-0.

- Mallick, P. K. (15 March 2010). Materials, design and manufacturing for lightweight vehicles. Woodhead publishing. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-1-84569-463-0.

- United States Department of Labor. "Polymer Matrix Materials: Advanced Composites".

- Jawaid, Mohammad; Thariq, Mohamed; Saba, Naheed (3 October 2018). Mechanical and Physical Testing of Biocomposites, Fibre-Reinforced Composites and Hybrid Composites. Elsevier. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-08-102292-4.

- Tatara, Robert A. (2011). Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook. Elsevier. p. 289.

- Meola, Carosena; Boccardi, Simone; Carlomagno, Giovanni Maria (29 June 2016). Infrared thermography in the evaluation of aerospace composite materials. Elsevier. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-78242-172-6.

- Jawaid, Mohammad; Thariq, Mohamed; Saba, Naheed (3 October 2018). Mechanical and Physical Testing of Biocomposites, Fibre-Reinforced Composites and Hybrid Composites. Elsevier. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-08-102292-4.

- FibreGlast. "Composite Laminate Cutting".