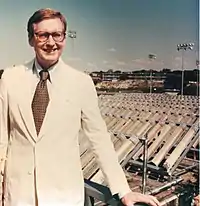

Leonard L. Northrup Jr.

Leonard "Lynn" L. Northrup Jr. (March 18, 1918 – March 24, 2016) was an American engineer who was a pioneer of the commercialization of solar thermal energy.[1][2] Influenced by the work of John Yellott, Maria Telkes, and Harry Tabor, Northrup's company designed, patented, developed and manufactured some of the first commercial solar water heaters, solar concentrators, solar-powered air conditioning systems, solar power towers and photovoltaic thermal hybrid systems in the United States. The company he founded became part of ARCO Solar, which in turn became BP Solar, which became the largest solar energy company in the world. Northrup was a prolific inventor with 14 US patents.

Leonard L. Northrup Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 18, 1918 |

| Died | March 24, 2016 (aged 98) Dallas, Texas |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Southern Methodist University University of Denver Harvard University |

| Known for | Active and Passive Solar technology, Stone Architecture |

| Awards | ASHRAE American Institute of Architects Patents |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Solar engineering |

| Institutions | NASA Sandia Labs Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory US Department of Energy Energy Research and Development Administration |

| Influences | John Yellott Harry Tabor Maria Telkes |

Early life, education, academia, and military service

Lynn Northrup Jr., a fourth generation Texan, was the son of L. L. Northrup Sr., an inventor in his own right, and Dolly McKaskle Northrup, a retail entrepreneur, both members of pioneer Texas families. He was educated at Woodrow Wilson High School in Dallas, Texas, and received a BA from Southern Methodist University, a MS from the University of Denver, and a Master of Business Administration from Harvard Business School. Northrup served as a captain the United States Army Corps of Engineers during and shortly after World War II.

Early work in automotive and residential air conditioning

After the War, Northrup went to work for Storm Vulcan, a Dallas company, where he invented a machine to clean aircraft engines.[3][4] He also embarked on a venture to fit cars with air conditioning equipment, putting the machinery in the trunk and piping the cooled air through tubes in the headliner. This caught the interest of engineers from General Motors, who copied the system in Cadillacs in the late 1940s. "After market" automotive AC units were manufactured in Texas until the 1980s. He also sold some of the first air conditioning units, built by the Curtis Mathes Corporation, an early leader in manufacturing window units.[5] Northrup married Jane Keliher and started a family in Dallas, where he designed and built one of the first single-family houses in the United States with central air conditioning. He founded a company to install air conditioning in residential and commercial buildings. With a Marketing Plan from G F Sweetman (CEO of American Awards Co), he became one of largest suppliers of Curtis Mathes fans and compressors in the nation. He also developed a company to manage, install, update, and clean air filtration systems.

Commercialization of solar thermal technology in the US

In the late 1960s, Northrup bought a controlling interest in Donmark Corporation, a manufacturer of residential air conditioning and heating equipment from Curtis Mathes, his lifelong friend. Northrup promoted the use of “all electric” central heating and cooling equipment, building a manufacturing facility in Dallas and later in Hutchins, Texas and selling primarily to apartment developers. In designing these systems, Northrup focused on the total installed cost of the unit, including the framing and plumbing costs.

During the mid-1970s, Northrup became interested in boosting the efficiency of air conditioning systems, and began looking at novel approaches, including water-source geothermal heat pumps, and the innovative use of scroll compressors in split system central air conditioning systems to achieve a higher efficiency rating, which have since become the standard compressor for high-efficiency residential air conditioning equipment.

In the early 1970s, before the Arab Oil Embargo and the spike in oil prices, Northrup became interested in the commercialization of solar thermal systems, particularly for heating potable water and swimming pools. Such systems had already been commercialized in other countries where climatic conditions were favorable, energy costs were high, and there was a tradition of scientific innovation notably solar power in Israel. Work in the United States had been limited to academia and a few companies in Arizona, Texas, and California. Northrup began experimenting with solar collectors to heat air, using finned heat exchangers, and engaged solar pioneer Professor John Yellott as a consultant on the absorptivity and emissivity or various surfaces and configurations, and on the transparency of various glasses and glazing material that exhibit the "greenhouse effect" - transparent to incoming solar radiation, but opaque to the re-radiation of infrared from the heated surface - hence a thermal trap or collector that exhibits the "greenhouse effect".

Additionally, he hired Maria Telkes, an expert on phase change materials, particularly molten salts, as a way to store thermal energy, and consulted with Israeli solar thermal pioneer Harry Tabor on surface coatings, including “black chrome” for solar panels. This work lead to the commercialization of flat panel solar water heaters, and solar pool heaters, marketed as Northrup Energy products directly and via dealers, with particular success in Hawaii, where solar thermosiphon systems could be used with antifreeze. With low temperature products in production and distribution, Northrup turned his attention to achieving higher temperatures – which would entail various methods of concentrating incoming insolation and tracking the sun - with varying degrees of success.

First Commercial Tracking Concentrating Solar Collectors

Northrup’s break-through technology was a collector[6] that used a long curved acrylic fresnel lens to concentrate or focus sunlight at a theoretical ratio of approximately 12 to 1 onto a linear flat copper tube, coated with a variant of Dr. Tabor's “black chrome” absorptive surface. The array, approximately 10’ long, tracked the movement of the sun during the day (east to west), automatically, with the elevation generally fixed (at approximately the same angle from horizontal as the latitude of the installation). The tracking device was ingenious – it consisted of two photoelectric cells at the base of a tube with a baffle between them. Current from the cells went to a control board that controlled the tracking motor. When the cell output was equalized, the baffle and the tube would be pointing at the sun. This was sufficient to enable the array to track the sun’s azimuth and generate considerable heat, as reported in tests published in the ASHRAE Journal, which noted that ". . . the array of collectors . . .follow the sun from just after sunrise to just before sunset and often results in the collection of twice as many usable BTUs of energy at a higher temperature than provided by high quality flat plate collectors.".[7]

These arrays proved popular – and were used to drive absorption refrigeration equipment on large commercial installations at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas,[8] at Frenchman’s Reef Hotel in St Thomas, USVI, residences,[9] and were sold to prominent individuals, including movie actor and entrepreneur Steve McQueen, actor Stuart Whitman and environmentalist Robert Redford.

The early success of these concentrating collectors was due in part to grants from the Department of Energy and its predecessor the Energy Research and Development Administration. They created a good deal of publicity for Northrup, Inc., including the cover of Popular Science Magazine[10] and an article in Fortune Magazine that noted, "By squeezing (sic) sunshine optically, Lynn Northrup's unique new rooftop solar collector produces higher temperatures than are obtainable from most solar heating systems now on the market".[11] Technically, these concentrating collectors were among the first commercially successful “east-west” tracking solar collectors. The fundamentals of their systems are still in use in daily azimuth and elevation tracking parabolic collectors. Most linear concentrating collectors are, as of this writing in 2010, of the less costly and less complicated seasonal tracking variety in the form of parabolic troughs.

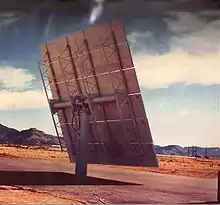

First Commercial Heliostats and Power Towers

Emboldened with his success in concentrating collectors, Northrup turned his attention to achieving higher temperatures, with azimuth and elevation tracking mirrors "heliostats" focused on a central boiler – ie. solar thermal power towers. The most advanced power tower at the time was an experimental tower in France, the Solar furnace at Odeillo, in the Pyrenees Orientales, which like other power towers, had been used solely for scientific purposes. Northrup attended a conference there in 1973 along with Professor Yellott and Floyd Blake, a former Martin Marietta senior aerospace engineer who had become interested in solar thermal research.

This interest led to hiring Blake and 16 other ex-aerospace engineers, who set up a research center in Littleton, Colorado, near Denver. The first Northrup, Inc. azimuth/elevation mirror array[12] was built with Northrup, Inc funds and a grant from the State of Texas. Designed by Blake’s team, the mirror array, dubbed "Northrup I", was assembled at the Northrup Energy manufacturing plant near Hutchins, Texas. It utilized multiple flat mirrors, with a weather-proof backing that became an industry standard. Each mirror was angled to the anticipated focal length to the central tower. Each moment of each year, each mirror had to be in a position to split the vectors between the mirror and the sun and the mirror and the target. This required a large volume of calculations, special computers and gearing mechanisms which Northrup designed. Team leader, Floyd Blake remembers, "Lynn climbed a ladder in front of the heliostats to take a picture of the sun reflected in them, then went up in a helicopter to be sure the heliostats were pointing correctly."

Northrup, Inc. was soon an industry leader in pre-commercial and commercial power tower and heliostat installations,[13] securing grants from NASA Huntsville, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, the United States Department of Energy, and the Energy Research and Development Administration. Most of the heliostats, including the Northrup II, a commercial model, were developed under contract for the United States Department of Energy. The heliostats focused radiation from the sun to generate temperatures up to 2,000 degrees at the target. Northrup, Inc. joint-ventured with the Bechtel Corp., which was responsible for designing the heliostat's target, a steam boiler.

ARCO Solar

By the late 1970s, just five years after testing the first low temperature solar thermal collectors, Northrup Energy had become the preeminent developer of solar thermal technology. This attracted the attention of investors, and suitors, including the Atlantic Richfield Company, “ARCO”. ARCO's Chairman, Robert O Anderson was personally interested in solar technology and visited the Northrup Energy facility. Northrup, Inc. merged with Atlantic Richfield, and ARCO Ventures changed its name to ARCO Solar. The Northrup Energy team under Floyd Blake and Jerry Anderson went on to design and build some of the first commercial solar power tower installations, notably "Solar One" near Barstow, California. The heat from another project was used to generate steam for tertiary oil recovery in Kern County, California and for electric power generation. Some heliostats were built to directly track the sun with arrays of photovoltaic cells to generate power for the utility grid, near Hesperia, California.[14] The seven million watt installation near Barstow was later dismantled and shipped to Europe's first commercial solar thermal power station. This unit was the largest solar electric power generation facility in the world. Northrup and Blake were then featured in a documentary on solar energy, Harnessing the Sun,[15] narrated by actress Joan Hackett.

ARCO Solar increasingly concentrated on the development of solar photovoltaic systems and was subsequently sold first to Seimens, then to British Petroleum (now "BP"), where BP Solar became the largest solar photovoltaic company in the world.

Northrup’s designs and work in flat plate solar thermal collectors, east–west tracking collectors and heliostats are still in use today and serve as the foundations of solar thermal technology. To acknowledge Prof. John Yellott's contributions to the advancements of solar thermal systems, Northrup endowed a chair at Arizona State in Yellott's honor. Northrup has, in turn, been honored for his contributions to the commercialization of solar technologies by the American Institute of Architects and the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers.

Work In Real Estate and Architectural Systems

After the merger of Northrup, Inc. into ARCO, Northrup became engaged in real estate development, including the assembly of one of the largest tracts of land in downtown Dallas, where he entered into a joint venture with James Rouse’s Enterprise Development Company to build a festival marketplace. This project was sold to a Belgian investment group who failed to pursue the project with Rouse. Northrup helped fund the establishment of Rouse's Enterprise Foundation affordable housing projects in Dallas. He also assembled tracts on 1½ miles of shoreline on Lewisville Lake, a part of which later became the city of The Colony. Northrup acquired 5,000 acres outside San Antonio, Texas, which was put into a trust for his family, and assembled land now occupied by the regional Rolex headquarters, among others.

Northrup subsequently started American Limestone, an innovator in using surface quarried Texas limestone in building facades, using a patented method[16] that employs thin panels of limestone as a veneer, attached to a metal grid without mortar. This popularized the use of rough cut limestone as a thin veneer in residential and commercial applications, including store fronts, such as Brooks Brothers, churches, bank buildings and municipal buildings. At the other extreme in size, Northrup has utilized massive blocks of limestone for their passive heating / cooling characteristics, and free-standing structural qualities, most notably donating the stone and devising the construction technique for the Cistercian Chapel in Irving, Texas, which reflects both a classic design aesthetic and construction technique of mortar-less masonry - a thoroughly modern building built in the rational style of Cistercian architecture. The architect, Gary Cunningham, said "We wanted to build a church that would literally last for the next 900 years".[17]

Awards

Engineering Achievement Award, American Society of Heating, Refrigeration, and Air Conditioning Engineers

Citation of Honor Award, American Institute of Architects for pioneering development of solar energy as a viable industry

Honorary Member of Beta Beta Beta, biological honor society in recognition of significant contributions and outstanding service to society and biology

Complete US Patents

| Date Filed | Patent No | Description |

|---|---|---|

| October 4, 1951 | US 2825349 | Parts Cleansing Machines[3] |

| April 30, 1954 | US 2838289 | Means for Cleaning Equipment[4] |

| April 9, 1973 | US 3852695 | Electrical Switching System |

| April 16, 1973 | US 3912903 | Electric Heating Device for Air Duct |

| September 3, 1974 | US 3977467 | Air Conditioning Module[5] |

| March 20, 1975 | US 3991741 | Roof-lens Solar Collector[6] |

| September 10, 1975 | US 4022186 | Compound Lens Solar Energy System |

| December 1, 1977 | US 4180985 | Air Conditioning System with Regeneratable Desiccant Bed |

| October 23, 1978 | US 4227513 | Solar System Having Improved Heliostat and Sensor Mountings[12] |

| November 13, 1978 | US 4276872 | Solar System Employing Ground Level Heliostats and Solar Collectors[13] |

| July 27, 1988 | US 4962695 | Broiler Oven |

| April 28, 1994 | US 5473851 | Limestone Curtain Wall System and Method[16] |

| May 11, 2006 | US 7347918 | Energy Efficient Evaporation System |

Northrup's May 2006 patent describes a method with the potential for using water as a general refrigerant, as well as an economical method of desalinating water.

Film Appearances

Harnessing The Sun (1980) [15]

See also

References

- "You searched for Leonard-Nothrup". Restland of Dallas | Funeral | Cremation | Cemetery.

- "Lynn Northrup Solar Energy Pioneer 1918 – 2016". No Fracking Way. 2016-03-25.

- US 2825349 Parts Cleansing Machines

- US 2838289 Means for Cleaning Equipment

- US 3977467 Air Conditioning Module

- US 3991741 Roof-lens Solar Collector

- ASHRAE Journal, November 1976 "Evaluating a Solar Energy Concentrator" Dr. Richard L. Pendleton

- "Solar project description for Trinity University power plant #2 (Open Library)".

- Solar Engineering January 1976, pp. 8–9

- Popular Science, October 1976

- Fortune Magazine, February 1976, page 108.

- US 4227513 Solar System Having Improved Heliostat and Sensor Mountings

- US 4276872 Solar System Heliostats and Collectors

- Arnett, J. C.; Schaffer, L. A.; Rumberg, J. P.; Tolbert, R. E. L. (1984). "Design, installation and performance of the ARCO Solar one-megawatt power plant". 5Th Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference: 314. Bibcode:1984pvse.conf..314A.

- Harnessing the Sun (1980) at IMDb

- US 5473851 Limestone Curtain Wall System and Method

- Architecture October 1992 p 61- 70

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leonard L. Northrup Jr.. |

- Leonard L. Northrup Jr. at IMDb

- Cistercian Chapel Project Page at Cunningham Architects

- Cistercian Chapel

- The Colony