Lepidurus apus

Lepidurus apus, commonly known as a tadpole shrimp, is a notostracan in the family Triopsidae, one of a lineage of shrimp-like crustaceans that have had a similar form since the Triassic period and are considered living fossils. This species is cosmopolitan, inhabiting temporary freshwater ponds over much of the world, and the most widespread of the tadpole shrimps. Like other notostracans, L. apus has a broad carapace, long segmented abdomen, and large numbers of paddle-like legs. It reproduces by a mixture of sexual reproduction and self-fertilisation of females.

| Lepidurus apus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Branchiopoda |

| Order: | Notostraca |

| Family: | Triopsidae |

| Genus: | Lepidurus |

| Species: | L. apus |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepidurus apus | |

Description

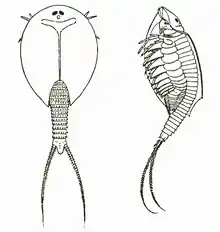

Lepidurus apus grows to 4.2–6.0 cm (1.7–2.4 in) in length. Its long abdomen is divided into about 30 segment-like rings, with two long caudal rami or "tails" attached behind the last ring.[1] Between the tails is a projection which distinguishes Lepidurus from Triops, the other notostracan genus. Its carapace is flat with an average length of 1.9 cm (0.75 in), and is attached only at the front, covering up to two thirds of the abdomen. The carapace is a mottled dark yellow/brown colour transitioning to a lighter edge, and bears a single pair of compound eyes.[2] At the front of the abdomen are one or more (up to three) pairs of feelers. Under the body are 41–46 (average 44) pairs of paddle-like limbs used for swimming.[3]

Males are readily identifiable by the lack of ovisacs, and also have subtle differences in the carapace. Females and hermaphrodites look virtually identical, but hermaphrodites have testicular lobes amongst their ovarian lobes, which allows them to reproduce in isolation.

L. apus is often referred to as a ‘living fossil’, virtually unchanged for over 300 million years. However, a recent study suggests that resemblance to fossil notostracans is probably a result of the "highly conserved general morphology in this group and of homoplasy". Recent species of Lepidurus are morphologically nearly identical to fossil records but may "represent very different evolutionary lineages".

Distribution and habitat

Global range

Lepidurus apus is perhaps the most cosmopolitan of all the Notostraca, occurring widely around the world including, but not limited to, New Zealand, Australia, Iran, [1] Israel, [4] France, Germany, Italy,[5] Denmark,[6] Morocco,[7] and Austria. Lepidurus apus is split into several geographic subspecies, such as L. apus viridis, present in parts of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand.[8]

Habitat preferences

Lepidurus apus is found predominantly in temporary freshwater ponds, 10–100 cm deep, filled during autumn and winter, and drying out over spring and summer. It is less common in permanent water bodies such as swamps and ditches. Lepidurus apus viridis, for example, is found throughout New Zealand in small ponds and ditches.[8] Its life-cycle allows it to become dormant if the pond freezes over, is covered with snow, or dries out; it can persist in the dry sediment margin as a cyst form, which can survive harsh conditions for many years until the pond reappears.[7] L. apus prefers a pH between 6 and 7.8, and can tolerate relatively high concentrations of chemicals, such as levels of total nitrate of 1 mg/L and phosphate of 0.1 mg/L, a level which would be detrimental to other aquatic species.[1]

Wetlands and temporary ponds worldwide are increasingly being converted to grasslands for agriculture, so the total land area available for L. apus is gradually diminishing. Some subspecies may become threatened in future, or may already be under threat, although our knowledge is limited.[8][9] L. apus is well-adapted to variations of climate and location, disperses easily, and has highly resilient eggs, so appears to be less sensitive to human pressures across its wide geographical range.

Life cycle

Lepidurus apus has an unusual life-cycle: it is able to produce microscopic cysts that can lie dormant for years at a time through extreme conditions, letting it survive in areas with vastly different climates such as Morocco and Denmark. These "resting eggs" are so drought resistant there is a record of hatching after being kept dry for 28 years.

The species is hermaphroditic; no males are found in the New Zealand subspecies viridius,[8] but in Italy there are males that are non-functional.[10] Different subspecies of Lepidurus apus have different methods of fertilisation, some by a male, some by hermaphroditic individuals.

Cysts average 0.447 mm in diameter,[9] and have been found at concentrations of 250 per 100 cm2.[7] They are laid on gravel in the middle of ditches or ponds, to avoid (it is speculated) large animals such as sheep transporting the cysts onto land.[7] The cysts can survive drought and sub-zero temperatures,[1] and can even synthesise haemoglobin if there is a lack of oxygen.[8] As the pond dries out in the summer, the cysts will lie dormant until immersed in water. Light is an important factor in hatching: experiments showed no cysts hatched in darkness, some hatched after 10 mins of bright light, and all hatched in continuous light.[9] They hatched between 10 °C and 24 °C, though the optimum was 16 °C and 20 °C, and even then hatch rates did not exceed 60%.[9]

Hatching often happens after winter rainfall forms temporary ponds. Larvae feed and rapidly grow to maturity, in as little as 4 weeks in optimum conditions in the warmer summer and spring months.[8]

Lepidurus apus has been found globally in remote areas with no waterways to transport individuals. In dry conditions, the dust-like resting eggs are easily distributed by wind. Lepidurus apus eggs are also though to be distributed by water, people, wildlife, and migratory birds.[1]

Diet

Lepidurus apus is omnivorous, feeding on both plant matter, mostly floating detritus, and small aquatic invertebrates such as Branchinecta and Daphnia.[3] It swims along the bottom of ponds, stirring up the substrate as it forages. The genus Lepidurus also feeds upon algae, myxozoa, bacteria and fungi.[2]

Predators and parasites

Predators of Lepidurus include small wading birds such as sandpipers or stint, larger waterfowl like ducks and swans, and, in some ponds, fishes.[2] Migrating birds feed from temporary pools, as well as itinerant birds already found in the area. The rapid abundance of Lepidurus apus and other small invertebrates in pools often results in an increase in bird numbers in the area.

Nosema lepiduri is a microsporidian parasite found in water bodies less than 15 cm deep that internally parasitises Lepidurus with spores, in some cases killing the host. Infected Lepidurus have a milky white colouration on the legs and carapace due to internal infection.[11]

Conservation status

The subspecies Lepidurus apus viridis has been classified by the New Zealand Department of Conservation as Nationally Endangered under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[12]

References

- Behroz, Atashbar; Naser, Agh; Lynda, Beladjal; Johan, Mertens (2013). "On the occurrence of Lepidurus apus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Crustacea, Notostraca) from Iran". Journal of Biological Physics and Chemistry. 19: 75–79.

- "Lepidurus apus". Encyclopedia of Life.

- "Tadpole Shrimps (Triopsidae: Lepidurus)". Landcare Research. 2015.

- Kuller, Z.; Gasith, A. (1996). "Comparison of the hatching process of the tadpole shrimps Triops cancriformis and Lepidurus apus lubbocki (Notostraca) and its relation to their distribution in rain-pools in Israel". Hydrobiologia. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 335 (2): 147–157. doi:10.1007/bf00015276. ISSN 0018-8158.

- Scanabissi, Franca; Mondini, Corrado (2002). "A survey of the reproductive biology in Italian branchiopods". Hydrobiologia. 486 (1): 263–272. doi:10.1023/a:1021371306687.

- Damgaard, Jakob; Olesen, Jørgen (1998). "Distribution, phenology and status for the larger Branchiopoda (Crustacea: Anostraca, Notostraca, Spinicaudata and Laevicaudata) in Denmark". Hydrobiologia. 377 (3): 9–13. doi:10.1023/A:1003256906580.

- Thiéry, Alain (1997). "Horizontal distribution and abundance of cysts of several large branchiopods in temporary pool and ditch sediments". Hydrobiologia. 359: 177–189. doi:10.1023/A:1003124617897.

- Collier, Kevin (1992). "Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of potential conservation interest" (PDF). Department of Conservation. p. 24.

- Kuller, Z; Gasith, A (1996). "Comparison of the hatching process of the tadpole shrimps Triops cancriformis and Lepidurus apus lubbocki (Notostraca) and its relation to their distribution in rain-pools in Israel". Hydrobiologia. 335 (2): 147–156. doi:10.1007/bf00015276.

- Scanabissi, Franca; Mondini, Corrado (October 2002). "A survey of the reproductive biology in Italian branchiopods". Hydrobiologia. 486: 263–272. doi:10.1023/a:1021371306687.

- Vavra, Jiri (1960). "Nosema lepiduri n. sp., a New Microsporidian Parasite in Lepidurus apus". The Journal of Protozoology. 7: 36–41. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1960.tb00704.x.

- Grainger, N.; Harding, J.; Drinan, T.; Collier, K.; Smith, B.; Death, R.; Makan, T.; Rolfe, J. (November 2018). "Conservation status of New Zealand freshwater invertebrates, 2018" (PDF). New Zealand Threat Classification Series. 28: 1–29 – via Department of Conservation.

External links

- The tadpole shrimp was discussed on RadioNZ Critter of the Week, 1 April 2016