Library of Celsus

The Library of Celsus is an ancient Roman building in Ephesus, Anatolia, now part of Selçuk, Turkey. The building was commissioned in the 110s A.D. by a consul, Gaius Julius Aquila, as a funerary monument for his father, former proconsul of Asia Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus,[1][2] and completed during the reign of Hadrian, sometime after Aquila's death.[3][4] The library is considered an architectural marvel, and is one of the only remaining examples of a library from the Roman Empire. The Library of Celsus was the third-largest library in the Roman world behind only Alexandria and Pergamum, believed to have held around twelve thousand scrolls.[5] Celsus is buried in a crypt beneath the library in a decorated marble sarcophagus.[6][7] The interior measured roughly 180 square metres (2,000 square feet).[8]

The interior of the library and its contents were destroyed in a fire that resulted either from an earthquake or a Gothic invasion in 262 C.E.,[9][7] and the façade by an earthquake in the tenth or eleventh century.[10] It lay in ruins for centuries until the façade was re-erected by archaeologists between 1970 and 1978.[11]

History

Celsus enjoyed a successful military and political career, having served as a commander in the Roman army before being elected to serve as a consul in Rome in 92 C.E.[3] Celsus, a native of Sardis, was one of the first men from the Greek-speaking eastern provinces to serve as a consul, the highest elected office in imperial Rome.[12] He was later appointed as proconsul, or governor, of Asia, the Roman province that covered roughly the same area as modern-day Turkey.[3] Celsus's son Aquila commissioned the library in his honor, though it was not completed until after Aquila's death. An inscription records that Celsus left a large legacy of 25,000 denarii to pay for the library's reading material.[4]

The library operated as a public space for the city from its completion around 117-135 C.E. until 262. The main floor functioned as a reading room, lit by abundant natural light from the eastern windows. Shelves or armaria set into niches along the walls held papyrus book rolls that visitors could read, though borrowing would not have been permitted because copies of books were rare and labor-intensive to produce. Additional scrolls may have been held in free-standing book boxes placed around the room, in which case the library would have had a holding capacity of up to sixteen thousand scrolls.[13]

The interior and contents of the library were destroyed by fire in 262 C.E., though it remains unknown whether this fire was the result of natural disaster or a Gothic invasion, as it seems the city was struck by one of each that year.[7][9] Only the façade survived, until an earthquake in eleventh or tenth century left it in ruins as well.[10]

Between 1970 and 1978, a reconstruction campaign was led by the German archaeologist Volker Michael Strocka. Strocka analysed the fragments that had been excavated by Austrian archaeologists between 1903 and 1904.[14] In the meantime, some of the architectural elements had been acquired by museums in Vienna and Istanbul. The absent fragments had to be replaced by copies or left missing.[11] Only the façade was rebuilt, while the rest of the building remains in ruin.

Architecture

The east-facing marble façade of the library is intricately decorated with botanical carvings and portrait statuary. Design features include acanthus leaves, scrolls, and fasces emblems, the latter being a symbol of magisterial power that alludes to Celsus's tenure as a consul.[15] The library is built on a platform, with nine steps the width of the building leading up to three front entrances. These are surmounted by large windows, which may have been fitted with glass or latticework.[16] Flanking the entrances are four pairs of Composite columns elevated on pedestals. A set of Corinthian columns stands directly above. The columns on the lower level frame four aediculae containing statues of female personifications of virtues: Sophia (wisdom), Episteme (knowledge), Ennoia (intelligence) and Arete (excellence).[17][18] These virtues allude to the dual purpose of the structure, built to function as both a library and a mausoleum; their presence both implies that the man for whom it was built exemplified these four virtues, and that the visitor may cultivate these virtues in him or herself by taking advantage of the library's holdings. This type of façade with inset frames and niches for statues is similar to that of the skene found in ancient Greek theatres and is thus characterised as "scenographic". The columns on the second level flank four podia, paralleling the aediculae below, which held statues of Celsus and his son.[3] A third register of columns may have been present in antiquity, though today only two remain.

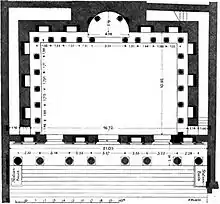

The interior of the building, which has yet to be restored, consisted of a single rectangular room measuring 17x11 m, with a central apse framed by a large arch at the far wall. The apse contained a podium for a statue, now lost, that likely depicted Celsus, although some scholars have suggested it was Minerva, goddess of wisdom.[19] A crypt containing Celsus's sarcophagus was located beneath the floor of the apse.[20][16] It was unusual in Roman culture for someone to be buried within a library or even within city limits, so this was a special honour for Celsus, reflecting his prominent role as a public official.

The three remaining walls were lined with either two or three levels of niches measuring 2.55x1.1x0.58 m on average, which would have held the armaria to house the scrolls.[21] These niches, which were backed with double walls, may have also had a function to control the humidity and protect the scrolls from the extreme temperature.[22] The upper level was a gallery with a balcony overlooking the main floor, creating a lofty spatial effect inside.[23] It could be reached via a set of stairs built into the walls, which added structural support. The ceiling was flat and may have had a central round oculus to provide more light.[24]

The design of the library, with its ornate, balanced façade, reflects the influence of Greek style on Roman architecture, which reached its height in the second century.

Portraiture of Celsus

The cuirassed statue of Celsus now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum was one of three statues of the building's patron located on the second level of the façade.[3] He is depicted with a strong jaw, curly hair, and a neat beard, Hellenizing portrait features that echo the stylistic choices of the building's façade.[15] The style imitates traits of Hadrianic imperial portraiture, suggesting that it was sculpted after the lifetime of not only Celsus, but of his son Aquila as well. The choice to depict him in full armor suggests that Celsus's descendants considered his military career memorable and a source of pride.

Commemoration

The building's façade was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 20 million lira banknote of 2001-2005[25] and of the 20 new lira banknote of 2005-2009.[26]

Footnotes

- Swain, Simon (2002). Dio Chrysostom: Politics, Letters, and Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780199255214.

Nevertheless, in 92 the same office went to a Greek, Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, who belonged to a family of priests of Rome hailing from Sardis; entering the Senate under Vespasian, he was subsequently to be appointed proconsul of Asia under Trajan, possibly in 105/6. Celsus' son, Aquila, was also to be made suffectus in 110, although he is certainly remembered more as the builder of the famous library his father envisioned for Ephesus.

- Nicols, John (1978). Vespasian and the partes Flavianae, Issues 28-31. Steiner. p. 109. ISBN 9783515023931.

Ti. Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (PIR2 J 260) was a romanised Greek of Ephesus or Sardes who became the first eastern consul.

- Smith, R. R. R. (1998). "Cultural Choice and Political Identity in Honorific Portrait Statues in the Greek East in the Second Century A.D.". The Journal of Roman Studies. 88: 56–93. doi:10.2307/300805. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 300805.

- Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 115.

- Planet, Lonely. "Library of Celsus - Lonely Planet". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Hanfmann, George Maxim Anossov (1975). From Croesus to Constantine: the cities of western Asia Minor and their arts in Greek and Roman times. University of Michigan Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780472084203.

...statues (lost except for their bases) were probably of Celsus, consul in A.D. 92, and his son Aquila, consul in A.D. 110. A cuirass statue stood in the central niche of the upper storey. Its identification oscillates between Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, who is buried in a sarcophagus under the library, and Tiberius Julius Aquila Polemaeanus, who completed the building for his father

- "Celsus Library, Ephesos". Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- "Library of Celsus". Ancient History Encyclopedia. 22 July 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Clyde E. Fant, Mitchell GReddish, A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 194.

- Clive Foss, Ephesus After Antiquity: A Late Antique, Byzantine, and Turkish City, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979, p. 134.

- Hartwig Schmidt, 'Reconstruction of Ancient Buildings', in Marta de la Torre (ed.), The Conservation of Archaeological Sites in the Mediterranean Region (Conference, 6–12 May 1995, Getty Conservation Institute), Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 1997, pp. 46-7.

- Richard Wallace, Wynne Williams (1998). The three worlds of Paul of Tarsus. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 9780415135917.

Apart from the public buildings for which such benefactors paid – the library at Ephesos, for example, recently reconstructed, built by Tiberius Iulius Aquila Polmaeanus in 110-20 in honour of his father Tiberius Iulius Celsus Polemaeanus, one of the earliest men of purely Greek origin to become a Roman consul

- Houston, George W. (2001). Inside Roman Libraries: Book Collections and Their Management in Antiquity. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 193.

- F. Hueber, V.M. Strocka, "Die Bibliothek des Celsus. Eine Prachtfassade in Ephesos und das Problem ihrer Wiederaufrichtung", Antike Welt 6 (1975), pp. 3 ss.

- Smith, R. R. R. (1998). "Cultural Choice and Political Identity in Honorific Portrait Statues in the Greek East in the Second Century A.D.". The Journal of Roman Studies. 88: 56–93. doi:10.2307/300805. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 300805.

- Houston, George W. (2014). Inside Roman Libraries : Book Collections and Their Management in Antiquity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 189.

- "Ephesus Library". www.kusadasi.biz. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 116.

- Houston, George W. (2014). Inside Roman Libraries: Book Collections and Their Management in Antiquity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 191.

- Makowiecka, Elżbieta (1978). The origin and evolution of architectural form of Roman library. Wydaw-a UW. p. 65. OCLC 5099783.

After all, the library was simultaneously the sepulchral monument of Celsus and the crypt contained his sarcophagus. The very idea of honouring his memory by erecting a public library above his grave need not have been the original conception of Tiberius Iulius Aquila the founder of the library.

- Houston, George W. (2014). Inside Roman Libraries: Book Collections and Their Management in Antiquity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 189, 191.

- Ephesus.us. "Celsus Library, Ephesus Turkey". www.ephesus.us. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Houston, George W. (2014). Inside Roman Libraries: Book Collections and Their Management in Antiquity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 190.

- Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 117.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group - Twenty Million Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2008-11-22 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 8. Emission Group - Twenty New Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived 2009-02-24 at the Wayback Machine.

Announcement on the Withdrawal of E8 New Turkish Lira Banknotes from Circulation Archived 2009-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, 8 May 2007. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

References

- Boethius, Axel; J.B. Ward-Perkins (1970). Etruscan and Roman Architecture: The Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-300-05290-9.

- Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09721-4.

- Grant, Michael (1995). Art in the Roman Empire. London: Routledge. pp. 48–50. ISBN 978-0-415-12031-9.

- Houston, George W. 2014. Inside Roman Libraries: Book Collections and their Management in Antiquity. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. IBSN 978-1-469-63920-8.

- Robertson, D.S. (1964). Greek and Roman Architecture. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-521-09452-8.

- Scarre, Christopher (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome. London: Penguin. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-14-051329-5.

- Smith, R. R. R. "Cultural Choice and Political Identity in Honorific Portrait Statues in the Greek East in the Second Century A.D." The Journal of Roman Studies 88 (1998): 56-93. doi:10.2307/300805.

- "Greece and Asia Minor". The Cambridge Ancient History - XI. Cambridge University Press. pp. 618–619, 631. ISBN 978-0-521-26335-1.

- "Library, Rome". The Brill's New Pauly Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, volume 7. Brill Leiden. 2005. p. 502. ISBN 978-90-04-12259-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Celsus library in Ephesus. |

- classics.uc.edu, Architecture, classical studies, bibliography (Archived)

- Virtual reconstruction of the Celsus library in Ephesus, Turkey