Lindisfarne

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne,[3] commonly known as either Holy Island[4] or Lindisfarne,[5] is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland.[6] Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important centre of Celtic Christianity under Saints Aidan of Lindisfarne, Cuthbert, Eadfrith of Lindisfarne and Eadberht of Lindisfarne. After the Viking invasions and the Norman conquest of England, a priory was reestablished. A small castle was built on the island in 1550.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne

| |

|---|---|

_(15064111624).jpg.webp) Lindisfarne Castle | |

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne Location within Northumberland | |

| Population | 180 (27 March 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NU129420 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BERWICK UPON TWEED |

| Postcode district | TD15 |

| Dialling code | 01289 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

| Designated | 5 January 1976 |

| Reference no. | 70[2] |

Name and etymology

Name

Both the Parker and Peterborough versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 793 record the Old English name for Lindisfarne, Lindisfarena.[7]

In the 9th century Historia Brittonum the island appears under its Old Welsh name Medcaut.[8] The philologist Andrew Breeze, following up on a suggestion by Richard Coates, proposes that the name ultimately derives from Latin Medicata [Insula] (English: Healing [Island]), owing perhaps to the island's reputation for medicinal herbs.[9][10]

The soubriquet Holy Island was in use by the 11th century when it appears in Latin as Insula Sacra. The reference was to Saints Aidan and Cuthbert.[11]

In the present day 'Holy Island' is the name of the civil parish[12] and native inhabitants are known as 'Islanders'. The Ordnance Survey uses 'Holy Island' for both the island and the village, with 'Lindisfarne' listed either as an alternative name for the island[4] or as a name of 'non-Roman antiquity'.[13] "Locally the island is rarely referred to by its Anglo-Saxon name of 'Lindisfarne'" (according to the local community website www.lindisfarne.org.uk).[14] More widely, the two names are used somewhat interchangeably.[15] 'Lindisfarne' is invariably used when referring to the pre-conquest monastic settlement, the Priory ruins[16] and the Castle.[17] The combined phrase 'The Holy Island of Lindisfarne' has begun to be used more frequently in recent times, particularly when promoting the island as a tourist or pilgrim destination.[18][19]

Etymology

The name Lindisfarne has an uncertain origin. The -farne part may be Old English –fearena meaning "traveller".[20] The first part, Lindis-, may refer to people from the Kingdom of Lindsey in modern Lincolnshire, referring to either regular visitors or settlers.[21][22][23][24] Another possibility is that Lindisfarne is Brittonic in origin, containing the element Lind- meaning "stream or pool" (Welsh llyn),[20] with the nominal morpheme -as(t) and an unknown element identical to that in the Farne Islands.[20] Further suggested is that the name may be a wholly Irish formation, from corresponding *lind-is-, plus –fearann meaning "land, domain, territory".[20] Such an Irish formation, however, could have been based on a pre-existing Brittonic name.[20]

There is also a supposition that the nearby Farne Islands are fern-like in shape and the name may have come from there.[11]

Geography and population

.jpg.webp)

The island of Lindisfarne is located along the northeast coast of England, close to the border with Scotland. It measures 3.0 miles (4.8 km) from east to west and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from north to south, and comprises approximately 1,000 acres (400 hectares) at high tide. The nearest point to the mainland is about 0.8 miles (1.3 kilometres). It is accessible at low tide by a modern causeway and an ancient pilgrims' path that run over sand and mudflats and which are covered with water at high tide. Lindisfarne is surrounded by the 8,750-acre (3,540-hectare) Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve, which protects the island's sand dunes and the adjacent intertidal habitats. As of 27 March 2011, the island had a population of 180.[25]

Community

A February 2020 report provided an update on the island. At the time, three pubs and a hotel were operating; the store had closed but the post office remained in operation. No professional or medical services were available and residents were driving to Berwick-upon-Tweed for groceries and other supplies. Points of interest for visitors included Lindisfarne Castle operated by the National Trust,[17] the priory, the historic church, the nature reserve and the beaches. At certain times of year, numerous migratory birds can be seen.[26]

Causeway safety

Warning signs urge visitors walking to the island to keep to the marked path, to check tide times and weather carefully, and to seek local advice if in doubt. For drivers, tide tables are prominently displayed at both ends of the causeway and also where the Holy Island road leaves the A1 Great North Road at Beal. The causeway is generally open from about three hours after high tide until two hours before the next high tide, but the period of closure may be extended during stormy weather. Tide tables giving the safe crossing periods are published by Northumberland County Council.[27]

Despite these warnings, about one vehicle each month is stranded on the causeway, requiring rescue by HM Coastguard and/or Seahouses RNLI lifeboat. A sea rescue costs approximately £1,900 (quoted in 2009, equivalent to £2,570 in 2019[lower-alpha 1]), while an air rescue costs more than £4,000 (also quoted in 2009, equivalent to £5,400 in 2019[lower-alpha 1]).[28] Local people have opposed a causeway barrier primarily on convenience grounds.[29][28]

History

Early

The north-east of England was largely not settled by Roman civilians apart from the Tyne valley and Hadrian's Wall. The area had been little affected during the centuries of nominal Roman occupation. The countryside had been subject to raids from both Scots and Picts and was "not one to attract early Germanic settlement".[30] King Ida (reigned from 547) started the sea-borne settlement of the coast, establishing an urbs regia[lower-alpha 2] at Bamburgh across the bay from Lindisfarne. The conquest was not straightforward, however. The Historia Brittonum recounts how, in the 6th century, Urien, prince of Rheged, with a coalition of North British kingdoms, besieged Angles led by Theodric of Bernicia on the island for three days and nights, until internal power struggles led to the Britons' defeat.[31][32]

Lindisfarne Priory

The monastery of Lindisfarne was founded around 634 by Irish monk Saint Aidan, who had been sent from Iona off the west coast of Scotland to Northumbria at the request of King Oswald. The priory was founded before the end of 634 and Aidan remained there until his death in 651.[33] The priory remained the only seat of a bishopric in Northumbria for nearly thirty years.[33] Finian (bishop 651–661) built a timber church "suitable for a bishop's seat".[34] St Bede, however, was critical of the fact that the church was not built of stone but only of hewn oak thatched with reeds. A later bishop, Eadbert, removed the thatch and covered both walls and roof in lead.[35] An abbot, who could be the bishop, was elected by the brethren and led the community. Bede comments on this:

And let no one be surprised that, though we have said above that in this island of Lindisfarne, small as it is, there is found the seat of a bishop, now we say also that it is the home of an abbot and monks; for it actually is so. For one and the same dwelling-place of the servants of God holds both; and indeed all are monks. Aidan, who was the first bishop of this place, was a monk and always lived according to monastic rule together with all his followers. Hence all the bishops of that place up to the present time exercise their episcopal functions in such a way that the abbot, who they themselves have chosen by the advice of the brethren, rules the monastery; and all the priests, deacons, singers and readers and other ecclesiastical grades, together with the bishop himself, keep the monastic rule in all things.[36]

Lindisfarne became the base for Christian evangelism in the North of England and also sent a successful mission to Mercia. Monks from the Irish community of Iona settled on the island. Northumbria's patron saint, Saint Cuthbert, was a monk and later abbot of the monastery, and his miracles and life are recorded by the Venerable Bede. Cuthbert later became Bishop of Lindisfarne. An anonymous life of Cuthbert written at Lindisfarne is the oldest extant piece of English historical writing. From its reference to "Aldfrith, who now reigns peacefully" it must date to between 685 and 704.[37] Cuthbert was buried here, his remains later translated[lower-alpha 3] to Durham Cathedral (along with the relics of Saint Eadfrith of Lindisfarne). Eadberht of Lindisfarne, the next bishop (and saint) was buried in the place from which Cuthbert's body was exhumed earlier the same year when the priory was abandoned in the late 9th century.

Cuthbert's body was carried with the monks, eventually settling in Chester-le-Street before a final move to Durham. The saint's shrine was the major pilgrimage centre for much of the region until its despoliation by Henry VIII's commissioners in 1539 or 1540. The grave was preserved, however, and when opened in 1827 yielded a number of remarkable artefacts dating back to Lindisfarne. The innermost (of three) coffins was of incised wood, the only decorated wood to survive from the period. It shows Jesus surrounded by the Four Evangelists. Within the coffin was a pectoral cross 6.4 centimetres (2.5 in) across, made of gold and mounted with garnets and intricate tracery. There was a comb made of elephant ivory, a rare and expensive item in Northern England. Also inside was an embossed silver-covered travelling altar. All were contemporary with the original burial on the island. When the body was placed in the shrine in 1104, other items were removed: a paten, scissors and a chalice of gold and onyx. Most remarkable of all was a gospel (known as the St Cuthbert Gospel or Stonyhurst Gospel from its association with the college). The manuscript is in an early, probably original, binding beautifully decorated with deeply embossed leather.[38]

Following Finian's death, Colman became Bishop of Lindisfarne. Up to this point the Northumbrian (and latterly Mercian) churches had looked to Lindisfarne as the mother church. There were significant liturgical and theological differences with the fledgling Roman party based at Canterbury. According to Stenton: "There is no trace of any intercourse between these bishops [the Mercians] and the see of Canterbury".[39] The Synod of Whitby in 663 changed this. Allegiance switched southwards to Canterbury and thence to Rome. Colman departed his see for Iona and Lindisfarne ceased to be of such major importance.

In 735 the northern ecclesiastical province of England was established with the archbishopric at York. There were only three bishops under York: Hexham, Lindisfarne and Whithorn; whereas Canterbury had the twelve envisaged by St Augustine.[40] The Diocese of York encompassed roughly the counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire. Hexham covered County Durham and the southern part of Northumberland up to the River Coquet and eastwards into the Pennines. Whithorn covered most of Dumfries and Galloway region west of Dumfries itself. The remainder, Cumbria, northern Northumbria, Lothian and much of the Kingdom of Strathclyde formed the diocese of Lindisfarne.[41]

In 737 Saint Ceolwulf of Northumbria abdicated as King of Northumbria and entered the priory at Lindisfarne. He died in 764 and was buried alongside Cuthbert. In 830 his body was moved to Norham-upon-Tweed and later his head was translated to Durham Cathedral.[42]

Lindisfarne Gospels

At some point in the early 8th century, the famous illuminated manuscript known as the Lindisfarne Gospels, an illustrated Latin copy of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, was made probably at Lindisfarne and the artist was possibly Eadfrith, who later became Bishop of Lindisfarne. It is also speculated that a team of illuminators and calligraphers (monks of Lindisfarne Priory) worked on the text; however, their identities are unknown. Sometime in the second half of the 10th century a monk named Aldred added an Anglo-Saxon (Old English) gloss to the Latin text, producing the earliest surviving Old English copies of the Gospels. Aldred attributed the original to Eadfrith (bishop 698–721). The Gospels were written with a good hand, but it is the illustrations done in an insular style containing a fusion of Celtic, Germanic and Roman elements that are truly outstanding. According to Aldred, Eadfrith's successor Æthelwald was responsible for pressing and binding it and then it was covered with a fine metal case made by a hermit called Billfrith.[39] The Lindisfarne Gospels now reside in the British Library in London, somewhat to the annoyance of some Northumbrians.[43] In 1971 professor Suzanne Kaufman of Rockford, Illinois presented a facsimile copy of the Gospels to the clergy of the island.

Vikings

In 793, a raid of Vikings from Norway on Lindisfarne[44][lower-alpha 4] caused much consternation throughout the Christian west and is now often taken as the beginning of the Viking Age. There had been some other Viking raids, but according to English Heritage this one was particularly significant, because "it attacked the sacred heart of the Northumbrian kingdom, desecrating ‘the very place where the Christian religion began in our nation’".[48]

The D and E versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record:

Her wæron reðe forebecna cumene ofer Norðhymbra land, ⁊ þæt folc earmlic bregdon, þæt wæron ormete þodenas ⁊ ligrescas, ⁊ fyrenne dracan wæron gesewene on þam lifte fleogende. Þam tacnum sona fyligde mycel hunger, ⁊ litel æfter þam, þæs ilcan geares on .vi. Idus Ianuarii, earmlice hæþenra manna hergunc adilegode Godes cyrican in Lindisfarnaee þurh hreaflac ⁊ mansliht.[49]

In this year fierce, foreboding omens came over the land of the Northumbrians, and the wretched people shook; there were excessive whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. These signs were followed by great famine, and a little after those, that same year on 6th ides of January, the ravaging of wretched heathen men destroyed God's church at Lindisfarne.

The generally accepted date for the Viking raid on Lindisfarne is in fact 8 June; Michael Swanton writes: "vi id Ianr, presumably [is] an error for vi id Iun (8 June) which is the date given by the Annals of Lindisfarne (p. 505), when better sailing weather would favour coastal raids."[50][lower-alpha 5]

Alcuin, a Northumbrian scholar in Charlemagne's court at the time, wrote:

Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race ... The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets.[51]

During the attack many of the monks were killed, or captured and enslaved.[52]

The English seemed to have turned their back on the sea as they became more settled. Many monasteries were established on islands, peninsulas, river mouths and cliffs. Isolated communities were less susceptible to interference and the politics of the heartland. The amazement of the English at the raids from the sea must have been matched by the amazement of the raiders at such (to them) vulnerable, wealthy and unarmed settlements.[53]

These preliminary raids, mainly from Norway, unsettling as they were, were not followed up. The main body of the raiders passed north around Scotland.[54] The 9th-century invasions came not from Norway, but from the Danes from around the entrance to the Baltic.[54] The first Danish raids into England were in the Isle of Sheppey, Kent during 835 and from there their influence spread north.[55] During this period religious art continued to flourish on Lindisfarne, and the Liber Vitae of Durham began in the priory.[56]

By 866 the Danes were in York and in 873 the army was moving into Northumberland.[57] With the collapse of the Northumbrian kingdom the monks of Lindisfarne fled the island in 875 taking with them St Cuthbert's bones (which are now buried at the cathedral in Durham),[58] who during his life had been prior and bishop of Lindisfarne; his body was buried on the island in the year 698.[59]

Prior to the 9th century Lindisfarne Priory had, in common with other such establishments, held large tracts of land which were managed directly or leased to farmers with a life interest only. Following the Danish occupation land was increasingly owned by individuals and could be bought, sold and inherited. Following the Battle of Corbridge in 914 Ragnald seized the land giving some to his followers Scula and Onlafbal.[60]

Middle Ages

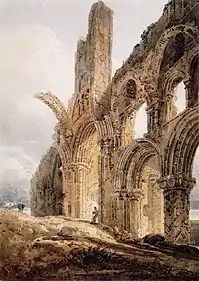

William of St Calais, the first Norman Bishop of Durham, endowed his new Benedictine monastery at Durham with land and property in Northumberland, including Holy Island and much of the surrounding mainland. Durham Priory re-established a monastic house on the island in 1093, as a cell of Durham, administered from Norham.[61] The standing remains date from this time (whereas the site of the original priory is now occupied by the parish church).

Monastic records from the 14th to the 16th century provide evidence of an already well-established fishing economy on the island.[62] Both line fishing and net fishing were practised, inshore in shallow waters and in the deep water offshore, using a variety of vessels: contemporary accounts differentiate between small 'cobles' and larger 'boats', as well as singling out certain specialised vessels (such as a 'herynger', sold for £2 in 1404).[63] As well as supplying food for the monastic community, the island's fisheries (together with those of nearby Farne) provided the mother house at Durham with fish, on a regular (sometimes weekly) basis. Fish caught included cod, haddock, herring, salmon, porpoise and mullet, among others. Shellfish of various types were also fished for, with lobster nets and oyster dredges being mentioned in the accounts. Fish surplus to the needs of the monastery was traded, but subject to a tithe.

There is also evidence that the monks operated a lime kiln on the island.[61]

In 1462, during the Wars of the Roses, Margaret of Anjou made an abortive attempt to seize the Northumbrian castles. Following a storm at sea 400 troops had to seek shelter on Holy Island, where they surrendered to the Yorkists.[64]

The Benedictine monastery continued until its suppression in 1536 under Henry VIII, after which the buildings surrounding the church were used as a naval storehouse.[61] In 1613 ownership of the island (and other land in the area formerly pertaining to Durham Priory) was transferred to the Crown.

An early scholarly description of the priory was compiled by Dr Henry George Charles Clarke (presumed son of Admiral Sir Erasmus Gower) [65] in 1838 during his term as president of the Berwickshire Naturalists' Club.[66] Dr Clarke surmised that this Norman priory was unique in that the centre aisle had a vault of stone. Of the six arches, Dr Clarke stated "as if the architect had not previously calculated the space to be occupied by his arcade. The effect here has been to produce a horse-shoe instead of a semicircular arch, from its being of the same height, but lesser span, than the others. This arch is very rare, even in Norman buildings". The Lindisfarne Priory (ruin) is a grade I listed building, List Entry Number 1042304.[67] Other parts of the priory are a Scheduled ancient monument, List Entry Number 1011650. The latter are described as "the site of the pre-Conquest monastery of Lindisfarne and the Benedictine cell of Durham Cathedral that succeeded it in the 11th century".[68]

Recent work by archeologists was continuing in 2019, for the fourth year. Artifacts recovered included a rare board game piece,[69] copper-alloy rings and Anglo-Saxon coins from both Northumbria and Wessex. The discovery of a cemetery led to finding commemorative markers "unique to the 8th and 9th centuries". The group also found evidence of an early medieval building, "which seems to have been constructed on top of an even earlier industrial oven" which was used to make copper or glass.[70]

St. Mary the Virgin

When the abbey was rebuilt by the Normans, the site was moved. The site of the original priory church was redeveloped in stone as the parish church. As such it is now the oldest building on the island still with a roof on. Remains of the Saxon church exist as the chancel wall and arch. A Norman apse (subsequently replaced in the 13th century) led eastwards from the chancel. The nave was extended in the 12th century with a northern arcade, and in the following century with a southern arcade.

After the Reformation the church slipped into disrepair until the restoration of 1860. The church is built of coloured sandstone which has had the Victorian plaster removed from it. The north aisle is known as the "fishermen's aisle" and houses the altar of St. Peter. The south aisle used to hold the altar of St. Margaret of Scotland, but now houses the organ.[71]

The church is a Grade I listed building number 1042304, listed as part of the whole priory.[67] The church forms most of the earliest part of the site and is a scheduled ancient monument number 1011650.[68]

For several years in the late 20th century (c. 1980~1990), religious author and cleric David Adam ministered to thousands of pilgrims and other visitors as rector of Holy Island.

Lindisfarne Castle

Lindisfarne Castle was built in 1550, around the time that Lindisfarne Priory went out of use, and stones from the priory were used as building material. It is very small by the usual standards, and was more of a fort. The castle sits on the highest point of the island, a whinstone hill called Beblowe.

After Henry VIII suppressed the priory, his troops used the remains as a naval store. In 1542 Henry VIII ordered the Earl of Rutland to fortify the site against possible Scottish invasion. By December 1547, Ralph Cleisbye, Captain of the fort, had guns including a wheel-mounted demi-culverin, two brass sakers, a falcon, and another fixed demi-culverin.[72] However, Beblowe Crag itself was not fortified until 1549 and Sir Richard Lee saw only a decayed platform and turf rampart there in 1565. Elizabeth I then had work carried out on the fort, strengthening it and providing gun platforms for the new developments in artillery technology. When James VI and I came to power in England, he combined the Scottish and English thrones, and the need for the castle declined. At that time the castle was still garrisoned from Berwick and protected the small Lindisfarne Harbour.

During the Jacobite Rising of 1715, Lancelot Errington, one of a number of locals who supported the Jacobite cause, visited the castle. Some sources say that he asked the Master Gunner, who also served as the unit's barber, for a shave.[73] Once Errington was inside, it became clear that most of the garrison were away; later that day he returned with his nephew Mark Errington, claiming that he had lost the key to his watch.[73] They were allowed in, overpowered the three soldiers present, and claimed the castle as a landing site for the Jacobite group led by Thomas Forster, Member of Parliament for the county of Northumberland.[74] Reinforcements did not arrive to support the Erringtons, so when a detachment of 100 men arrived from Berwick to retake the castle they were only able to hold out for one day. Fleeing, they were captured at the tollbooth at Berwick and imprisoned, but were later able to tunnel out of their gaol and escape.[73]

Lighthouses

| Location | Northumberland, United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 55.658189°N 1.793194°W |

| Automated | yes |

| Tower shape | quadrangular tower with balcony, red triangle and light (HH) |

| Tower height | 21 m (69 ft) (GPE) 25 metres (82 ft) (GPW) 8 metres (26 ft) (HH) |

| Focal height | 9 m (30 ft) (GPE); 24 metres (79 ft) (HH) |

| Light source | solar power |

| Range | 9 nmi (17 km; 10 mi) (GP) 5 nautical miles (9.3 km; 5.8 mi) (HH) |

| Characteristic | Oc WRG 6s. (GPE) metal skeletal tower (HH) |

| Admiralty number | A2816 |

| NGA number | 2262 |

| ARLHS number | ENG-222 (GP) ENG 314 (HH) |

| Managing agent | Trinity House[75] |

Trinity House operates two light beacons (which it lists as lighthouses) to guide vessels entering Holy Island Harbour. Until 1 November 1995 both were operated by Newcastle-upon-Tyne Trinity House (a separate corporation, which formerly had responsibility for navigation marks along the coast from Berwick-upon-Tweed to Whitby). On that day, responsibility for marking the approach to the harbour was assumed by the London-based Corporation.[76]

Heugh Hill Light is a metal framework tower with a black triangular day mark, situated on Heugh Hill (a ridge on the south edge of Lindisfarne). Prior to its installation, a wooden beacon with a triangle topmark had stood on the centre of Heugh Hill for many decades.[77] Nearby is a former coastguard station, recently refurbished and opened to the public as a viewing platform. An adjacent ruin is known as the Lantern Chapel; its origin is unknown, but the name may indicate an earlier navigation light on this site.

Guile Point East and Guile Point West are a pair of stone obelisks standing on a small tidal island on the other side of the channel. The obelisks are leading marks which, when aligned, indicate the safe channel over the bar. When Heugh Hill bears 310° (in line with the church belfry) the bar is cleared and there is a clear run into the harbour.[78] The beacons were established in 1826 by Newcastle-upon-Tyne Trinity House (in whose ownership they remain). Since the early 1990s, a sector light has been fixed about one-third of the way up Guile Point East.[75]

Not a lighthouse but simply a daymark for maritime navigation, a white brick pyramid, 35 feet high and built in 1810, stands at Emmanuel Head, the north-eastern point of Lindisfarne. It is said to be Britain's earliest purpose-built daymark.[79]

Emmanuel Head Beacon

Emmanuel Head Beacon Former coastguard station and remains of 'Lantern Chapel'

Former coastguard station and remains of 'Lantern Chapel'

Modern

A Dundee firm built lime kilns on Lindisfarne in the 1860s, and lime was burnt on the island until at least the end of the 19th century. The kilns are among the most complex in Northumberland. Horses carried limestone, along the Holy Island Waggonway, from a quarry on the north side of the island to the lime kilns, where it was burned with coal transported from Dundee on the east coast of Scotland. There are still some traces of the jetties by which the coal was imported and the lime exported close by at the foot of the crags. The remains of the waggonway between the quarries and the kilns makes for a pleasant and easy walk. At its peak over 100 men were employed. Crinoid columnals extracted from the quarried stone and threaded into necklaces or rosaries became known as St Cuthbert's beads. The large-scale quarrying in the 19th century had a devastating effect on the interesting limestone caves, but eight sea caves remain at Coves Haven.[80]

Workings on the lime kilns stopped by the start of the 20th century.[81] The lime kilns on Lindisfarne are among the few being actively preserved in Northumberland.[81]

Holy Island Golf Club was founded in 1907 but later closed in the 1960s.[82]

Present day

The island is within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty on the Northumberland Coast. The ruined monastery is in the care of English Heritage, which also runs a museum/visitor centre nearby. The neighbouring parish church (see below) is still in use.

Lindisfarne also has the small Lindisfarne Castle, based on a Tudor fort, which was refurbished in the Arts and Crafts style by Sir Edwin Lutyens for the editor of Country Life, Edward Hudson. Lutyens also designed the island's Celtic-cross war-memorial on the Heugh. Lutyens' upturned herring busses near the foreshore provided the inspiration for Spanish architect Enric Miralles' Scottish Parliament Building in Edinburgh.[83]

One of the most celebrated gardeners of modern times, Gertrude Jekyll (1843–1932), laid out a tiny garden just north of the castle in 1911.[17] The castle, garden and nearby lime kilns are in the care of the National Trust and open to visitors.[17]

Turner, Thomas Girtin and Charles Rennie Mackintosh all painted on Holy Island.

Holy Island was considered part of the Islandshire unit along with several mainland parishes. This came under the jurisdiction of the County Palatine of Durham until the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844.

Lindisfarne was mainly a fishing community for many years, with farming and the production of lime also of some importance.

The Holy Island of Lindisfarne is well known for mead. In the mediaeval days when monks inhabited the island, it was thought that if the soul was in God's keeping, the body must be fortified with Lindisfarne mead. The monks have long vanished, and the mead's recipe remains a secret of the family which still produces it; Lindisfarne Mead is produced at St Aidan's Winery, and sold throughout the UK and elsewhere.[84]

Today on the island it is possible to witness some old wooden boats turned upsite down on the land, looking like sheds. It is possible that this settlement was used by seafaring Vikings that exploited their ships as protection while away from home.[85]

The isle of Lindisfarne was featured on the television programme Seven Natural Wonders as one of the wonders of the North. The Lindisfarne Gospels have also featured on television among the top few Treasures of Britain. It also features in an ITV Tyne Tees programme Diary of an Island which started on 19 April 2007 and on a DVD of the same name.

Lindisfarne Abbey and St Marys

Lindisfarne Abbey and St Marys Lindisfarne lobster pots

Lindisfarne lobster pots Lindisfarne Castle from the harbour

Lindisfarne Castle from the harbour A Lindisfarne fisherman in 1942

A Lindisfarne fisherman in 1942 Upturned boats in the harbour of Lindisfarne used as sheds

Upturned boats in the harbour of Lindisfarne used as sheds

Community Trust Fund/Holy Island Partnership

In response to the perceived lack of affordable housing on the isle of Lindisfarne, in 1996 a group of islanders established a charitable foundation known as the Holy Island of Lindisfarne Community Development Trust. They built a visitor centre on the island using the profits from sales. In addition, eleven community houses were built and are rented out to community members who want to continue to live on the island. The trust is also responsible for management of the inner harbour. The Holy Island Partnership was formed in 2009 by members of the community as well as organisations and groups operating on the island.

Tourism

Tourism grew steadily throughout the 20th century, and the isle of Lindisfarne is now a popular destination for visitors. Those tourists staying on the island while it is cut off by the tide experience the island in a much quieter state, as most day trippers leave before the tide rises. At low tide it is possible to walk across the sands following an ancient route known as the Pilgrims' Way (see the note about safety, above). This route is marked with posts and has refuge boxes for stranded walkers, just as the road has a refuge box for those who have left their crossing too late. The isle of Lindisfarne is surrounded by the 8,750-acre (3,540-hectare) Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve which attracts bird-watchers to the tidal island. The island's prominent position and varied habitat make it particularly attractive to tired avian migrants, and as of 2016 330 bird species had been recorded on the island.[86]

Notes

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- urbs regia: "royal city", a royal settlement

- That is disinterred, moved and reburied

- Lindisfarne, or Holy Island, is a small tidal island off the coast of Northumbria where a monastery had been established in 634. Its shelving beaches provided a supposedly perfect landing for the shallow-draft ships of the Viking raiders who fell upon its unsuspecting and virtually unprotected monks in the summer of 793. This bloody assault on a "place more venerable than all in Britain" was one of the first positively recorded Viking raids on the west. Lindisfarne was supposedly a good place to attack because people in the dark ages would send their valuables to Lindisfarne, similar to a bank, for safekeeping.[45] Viking longships, with their shallow drafts and good manoeuvrability under both sail and oar, allowed their crews to strike deep inland up Europe's major rivers.[46] The world of the Vikings consisted of a loose grouping of the Scandinavian homelands and new overseas colonies, linked by sea routes that reached across the Baltic and the North Sea, spanning even the Atlantic.[47]

- This may be confusing to modern readers. The 6 refers to the number of days BEFORE the Ides, not after. The day itself was included, and so vi id was 6 days before the ides, counting the ides as 1. In June the ides falls on the 13th of the month, so vi id Jun was actually 8 June. See Roman calendar for full details.

Citations

- "Holy Island Ward population 2011". Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Lindisfarne". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Holy Island webmaster 2013.

- Ordnance Survey 2019.

- Britannia Staff Article.

- Northumberland County Council 2013.

- Freeborn, p. 39.

- Nennius 1848, section 65.

- Breeze 2008, pp. 187–8.

- Green 2020, p. 236.

- Simpson 2009.

- "Town and Parish Councils List". Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Ordnance_Survey 2015.

- "Welcome Visitor". The Holy Island of Lindisfarne. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Stanford, Peter (2010). The Extra Mile: A 21st Century Pilgrimage. London: Continuum. pp. 155-160.

- "Lindisfarne Priory". English Heritage. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- The National Trust 2020.

- "The Holy Island of Lindisfarne". Visit Northumberland. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Take a modern day pilgrimage to the Holy Island of Lindisfarne". Visit England. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- James 2019.

- Mills 1997, p. 221.

- Myers 1985, p. 175.

- Ekwall 1960, pp. 298–9.

- Green 2020, pp. 239–240.

- Office for National Statistics 2013.

- Express, Britain. "Lindisfarne Castle | Historic Northumberland". Britain Express.

- Holy Island webmaster 2019.

- Costello 2009.

- BBC 2011.

- Myers 1985, p. 198.

- Breeze 2008, p. 187-8.

- Myers 1985, p. 199.

- Stenton 1987, p. 118.

- Stenton 1987, p. 119.

- Loyn 1962, p. 275 quoting Bede 1896, II, 16; III, 25

- Bede c. 730 in Colgrave 1940, pp. 207–9 cited by Blair 1977, pp. 133–4

- Colgrave 1940, p. 104 cited by Stenton 1987, p. 88

- Campbell 1982, pp. 80–81.

- Stenton 1987, p. 120.

- Stenton 1987, p. 109.

- Blair 1977, p. 145 (map).

- Britannia_Staff_Article 1999.

- BBC 2008.

- Graham-Campbell & Wilson 2001, Salt-water bandits.

- Graham-Campbell & Wilson 2001, p. 21.

- Graham-Campbell & Wilson 2001, p. 22.

- Graham-Campbell & Wilson 2001, p. 10.

- "THE VIKING RAID ON LINDISFARNE". English Heritage. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

heathen men came and miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter.

- Jebson 2007, entry for 793.

- Swanton 2000, p. 57.

- Killeen 2012, p. 30.

- Marsden, John (1993). The Fury of the Northmen: Saints, Shrines and Sea-raiders in the Viking Age. London: Kyle Cathie. p. 41.

- Blair 1977, p. 63.

- Stenton 1987, p. 239.

- Stenton 1987, p. 243.

- Stenton 1987, p. 95.

- Stenton 1987, pp. 247–251.

- Stenton 1987, p. 332.

- Richards, Julian (2001). Blood of the Vikings. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 24.

- Richards 1991, pp. 30–31.

- Finlayson & Hardie 2009.

- Porteous 2018a.

- Porteous 2018b, p. 55.

- Jacob 1988, p. 533.

- Bates (2017), pp. 314-316.

- Clarke (1834), pp. 111-114.

- Historic England & 1042304.

- Historic England & 1011650.

- "Rare Viking Era Board Game Piece Discovered On Lindisfarne". Forbes. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- "Summer of finds on Lindisfarne". Current Publishing. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

a new glimpse at life on the island before, during, and after the 8th-century Viking raid that struck its monastic community.

- Brother Damian SSF 2009.

- Starkey 1998, p. 134.

- Hutson 2006.

- Müller & Barton 2009.

- Corporation of Trinity House 2016, Guile Point East.

- Corporation of Trinity House 2016, Heugh Hill.

- James Imray and Son 2010.

- Fowler 1990, p. 22:137.

- Jones 2014.

- Scaife 2019.

- The National Trust.

- Llewellyn & Llewellyn 2012, Holy Island Golf Club.

- BBC 2000.

- van Tuijl 2020.

- Richards, Julian (2001). Blood of the Vikings. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 24.

- Kerr 2016.

References

- Bates, Ian M (1 September 2017), Champion of the Quarterdeck: Admiral Sir Erasmus Gower 1742-1814, Pomona, Queensland: Sage Old Books, ISBN 978-0-9587021-2-6

- BBC (19 June 2011), "Holy Island tourists 'driving into North Sea'", BBC News, retrieved 11 August 2013

- BBC (20 March 2008), "Viz creator urges gospels return", BBC News, retrieved 4 August 2016

- BBC (3 July 2000), "Scots Parliament architect dies", BBC News, retrieved 22 February 2014

- Bede (1896) [written c.731], Plummer, C. (ed.), "Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum", Venerabilis Baedae Opera Historica, Oxford

- Bede (c. 730), The life of Cuthbert

- Blair, Peter Hunter (1977) [first edition 1959], An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.), OUP, ISBN 978-0-521-29219-1

- Breeze, Andrew (2008). "Medcaut, the Brittonic name of Lindisfarne". Northern History. 42: 187–8. doi:10.1179/174587005x38507. S2CID 161540990.

- Britannia Staff Article (1999), "St. Ceolwulf, King of Northumbria (c.AD 695-764)", britannia.com, archived from the original on 19 October 2017, retrieved 4 March 2018

- Britannia Staff Article, "Holy Island", britannia.com, retrieved 12 November 2019

- Brother Damian SSF (2009), St Mary's Parish Church – A brief tour, archived from the original on 23 July 2013, retrieved 14 August 2013

- Campbell, James (1982), The Anglo-Saxons, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9

- Clarke, Henry, MD (1834), "Holy Island Priory", History of the Berwickshire Naturalists' Club, Edinburgh, 1

- Colgrave, B, ed. (1940), The two lives of St Cuthbert, Cambridge

- Colvin, H M, ed. (1982) [1485–1600], The History of the King's Works, IV, London

- Corporation of Trinity House (2016), Lighthouses, retrieved 24 June 2019

- Costello, Paul (23 July 2009), Tidal tourists mystify islanders, BBC News, Newcastle, retrieved 11 August 2013

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960), Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (4th ed.), OUP

- Finlayson, Rhona; Hardie, Caroline (2009), Williams, Alan (revisor), Derham, Karen (Strategic Summary), "Holy Island (Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey)" (PDF), Northumberland County Council, Northumberland CC and English Heritage, retrieved 16 June 2020

- Fowler, Jean, ed. (1990), Reed's Nautical Almanac 1990, New Malden, Surrey: Thomas Reed Publications Limited, ISBN 978-0-947637-36-1

- Freeborn, Dennis, From Old English to Standard English: A Course Book in Language Variation across Time (2nd ed.)

- Graham, Peter Anderson, Lindisfarne Castle

- Graham-Campbell, James; Wilson, David M. (2001), The Viking World (Google Books) (3rd ed.), London: Frances Lincoln Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7112-1800-0, retrieved 1 December 2008

- Green, Caitlin (2020), Britons and Anglo-Saxons: Lincolnshire 400-650 AD (second ed.)

- Historic England, "Lindisfarne Priory pre-Conquest monastery and post-Conquest Benedictine cell (1011650)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 August 2013

- Historic England, "Lindisfarne Priory (1042304)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 14 August 2013

- Holy Island webmaster (2013), The Holy Island of Lindisfarne, retrieved 11 August 2013

- Holy Island webmaster (2019), Causeway Crossing Times 2019, retrieved 15 October 2017

- Hutson, Jeremy (20 September 2006), The History of Tudhoe Village: Dissent and Rebellion in County Durham, Durham University, retrieved 2 December 2014

- James Imray and Son (10 September 2010) [facsimile, original 1854], Sailing Directions for the East Coasts of England and Scotland: From Flamborough Head to Cape Wrath, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1-169-01175-5

- Jacob, E. F. (1988) [first published 1961], The Fifteenth Century, 1399–1485, The Oxford History of England, VI, OUP, ISBN 978-0-19-821714-5

- James, Alan G. (2019), "A Guide to the Place-Name Evidence - Guide to the Elements" (PDF), Scottish Place Name Society - The common Brittonic Language in the Old North

- Jebson, Tony (6 August 2007), Manuscript D: Cotton Tiberius B.iv: The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: An Electronic Edition, retrieved 12 August 2013

- Jones, Robin (2014), Lighthouses of the North East Coast, Wellington, Somerset: Halsgrove

- Kerr, Ian (2016), The Birds of Holy Island & Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve (3rd ed.), London: NatureGuides, ISBN 978-0-9544882-4-6

- Killeen, Richard (2012), A Brief History of Ireland, Running Press

- Llewellyn, John; Llewellyn, Marie (2012), Golf's missing links, retrieved 24 June 2019

- Loyn, H.R. (1962), Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-48232-6

- Mills, A. D. (1997), Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (2nd ed.), OUP

- Müller, Andrew J.; Barton, Roy (2009), Lindisfarne Castle, retrieved 2 December 2014

- Myers, J. N. L. (1985), The English Settlements, The Oxford History of England, 1B, OUP, ISBN 978-0-19-821719-0

- The National Trust, Holy Island Lime Kilns (Plaque outside Lime Kilns), Lindisfarne

- The National Trust (June 2020), Lindisfarne Castle, retrieved 16 September 2020

- Nennius (1848) [written c.829], Giles, J. A. (ed.), Historia Brittonum, London: Henry G. Bohn, retrieved 11 August 2013, published in "Six Old English Chronicles"

- Northumberland County Council (2013), Parish and town councils, retrieved 11 August 2013

- Office for National Statistics (30 January 2013), "Usual Resident Population, 2011 (KS101EW)", Neighbourhood Statistics, retrieved 21 February 2014

- Ordnance Survey (16 September 2015). Map of Holy Island & Bamburgh (Map). 1:25,000. Explorer. map 340. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Ordnance Survey (2019), Holy Island, Ordnance Survey, retrieved 12 November 2019

- Porteous, Katrina (13 May 2018), "Holy Island's Fishing Heritage", Islandshire Archives: A community history of Holy Island and the adjacent mainland, Peregrini Project, retrieved 16 June 2020CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Porteous, Katrina (4 December 2018), "Holy Island's Fishing Heritage" (PDF), Peregrini Lindisfarne - An Anthology, retrieved 16 June 2020CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Richards, Julian D. (1991), Viking Age England, English Heritage Book of ..., BCA, ISBN 978-0-7134-6519-8

- Scaife, Chris (2019), The Caves of Northumberland, Sigma Leisure, ISBN 978-1-910758-43-4

- Simpson, David (2009), "Place-Name Meanings K to O", Roots of the Region, retrieved 11 August 2013

- Starkey, David, ed. (1998), The Inventory of Henry VIII, 1, Society of Antiquaries

- Stenton, Sir Frank M. (1987) [first published 1943], Anglo-Saxon England, The Oxford History of England, II (3rd ed.), OUP, ISBN 978-0-19-821716-9

- Swanton, Michael (6 April 2000) [c.1000], The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (New ed.), Phoenix Press, ISBN 978-1-84212-003-3

- van Tuijl, Michael Vrieling (22 June 2020), "Lindisfarne Mead, Fruit Wines and Liqueurs", Holy Island of Lindisfarne, retrieved 23 June 2020

Further reading

- Aslet, Clive (1982), The Last Country Houses, London

- Baker, David (1975), Lutyena at Lindisfarne, Newscastle: unpublished B Arch thesis

- Brereton, Sir William (1844) [1635], Notes on a Journey through Durham and Northumberland in the Year 1635, Newcastle

- Brown, Jane (1996), Lutyens and the Edwardians, London

- Cornforth, John (1985), The Inspiration of the Past, Harmondsworth

- Festing, Sally (1991), Gertrude Jekyll, London

- Magnusson, Magnus (1984), Lindisfarne, The Cradle Island, Oriel Press, ISBN 978-0-85362-223-9

- Simpson, Ray (2013), A Holy Island Prayer Book: Prayers and Readings from Lindisfarne, UK: Canterbury Press, ISBN 978-1-85311-474-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lindisfarne. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lindisfarne. |

- Holy Island Safe Crossing Times

- Lindisfarne Priory Opening Times

- Lindisfarne Priory – English Heritage

- Video: Holy Island Causeway information

- Images of Lindisfarne Castle

- Holy Island Webcam Live

- Lindisfarne Castle

- Historic England. "Lindisfarne Priory (7835)". PastScape.

- Teachers' resource pack: English Heritage

- Lindisfarne Visitor Information Official Visitor Information for Holy Island of Lindisfarne