Linienwall

The Linienwall was an outer line of fortifications for the city of Vienna, Austria, which lay between the city's suburbs and outlying villages. Constructed in 1704, it was razed in 1894 to make way for the Vienna Beltway.

Building of the Linienwall

The construction of the Linienwall was begun by order of Emperor Leopold I in 1704 to protect against attacks by the Turks and the Kuruc (a group of anti-Habsburg rebels). It was part of a defensive line that followed the Austro-Hungarian border as delineated by the Danube, March, and Leitha rivers as well as by Lake Neusiedl.

All of the residents of Vienna and its suburbs between the age of 18 and 60 years old were required to work (or provide a replacement worker) on the fortifications, which consisted of a zigzagging, palisade-reinforced, earthen rampart, four metres high by four metres wide, and a three-metre-deep ditch. Construction was completed in only four months. In 1738, the earthworks were reinforced with a layer of bricks.

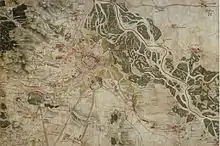

The fortifications encircled the suburbs from the Danube Canal at Sankt Marx (today Vienna’s 3rd District) to Lichtental (part of the 9th District), a distance of 13.5 km. It thus separated physically the Vorstädte or suburbs (today’s 3rd through 9th districts, incorporated into Vienna in 1850) from the Vororte or outlying places (today’s 10th through 19th districts, incorporated 1892). The most important arterial roads entered the city via drawbridges and gates; each of these locations additionally included a custom house where a toll, the Liniengeld was charged.

On June 11, 1704 the Linienwall helped a group of 2,600 Viennese residents along with 150 students repel an attack by the Kuruc.[1]

Linienwall Chapels

Between 1740 and 1760 a chapel dedicated to John of Nepomuk was built at each of the 18 city gates. These chapels were intended to provide a place for all travellers to and from the city to pray or hear mass at the city limit. The only remaining chapel still in its original position is the Hundsturmer Kapelle in the Margareten district. There is also an original chapel dedicated to Johannes Nepomuk am Tabor at the border between the 2nd and 20th districts, but it has been moved a few metres from its original position.

One of the chapels was removed during the construction of Otto Wagner's Vienna Metropolitan Railway in 1898. A replacement chapel was built at this time which now stands near the Vienna Volksoper between the viaduct for the railway (now part of the Vienna u-bahn) and the Vienna Beltway known as Gürtel.[2]

Toll zone limit

A foreign army never seriously tested the military utility of the Linienwall, but it did discourage raids by the aforementioned Kuruc. It did, however, help to protect the revolting citizens of Vienna during the Revolutions of 1848 from imperial forces.

From 1829 on, the walls (specifically the gates leading into the city) primarily served as a location to charge a road toll, the Liniengeld on modes of transport entering the city, therefore representing a fiscal and legal as well as physical limit to the city. The suburbs inside of the walls were thus taxed at a higher rate than those outside the walls even before their formal incorporation into the city in 1850. One consequence of this was the establishment of a great number of restaurants and hotels in the Neulerchenfeld (now part of the 16th District) right outside of the wall (dubbed the "Holy Roman Empire’s biggest pub") who took advantage of the lower taxes to sell food and drinks at a significantly cheaper rate.

Razing of the Linienwall

By the mid-19th century, long after the Linienwall had become militarily obsolete, Vienna was growing at a rapid rate. As railway and road construction kept pace with this growth, eventually the space occupied by the fortifications was replaced with transportation facilities. For example, in 1846 the terminus for the South Railway and East Railway was built right outside the Belvedere Gate at Südbahnhof (South Station). In 1858 another station, Wien Westbahnhof was built outside of Mariahilfer Gate. From 1862 to 1873, the first part of the ring roads (the Gürtel mentioned above) was built directly outside of the walls.

In 1874 the unincorporated parts of the 3rd, 4th, and 5th districts that lay outside of the wall were incorporated as a new 10th district, Favoriten. On 18 December 1890 the decision was made to incorporate the remaining outlying suburbs from 1 January 1892.[3] This decision rendered the fortifications as a duty control limit obsolete. The remainders of the Linienwall were removed in March 1894, leaving behind a very wide belt around the city. Starting in 1895 this area was filled with a second ring road as well as the viaduct for the Vienna Metropolitan Railway, which is how the area remains today.

Existing Relics

Besides the Hundsturmer Chapel, there are only a few sections of the Linienwall left which can be seen in the following locations:

- In the 3rd district along the tracks for the Vienna S-Bahn between Rennweg and Südbahnhof stations.

- In the area of a former cattle market in the Sankt Marx area of the 3rd District.

- In the yard of Weyringergasse 13 in the 4th District.

References

- Walter Blasi, Franz Sauer: Die Kuruzzenschanze zwischen Petronell und Neusiedl am See. In: Bundesdenkmalamt (publ.): Fundberichte aus Österreich - Materialhefte. Reihe A, Sonderheft 19 (FÖMat A/Sonderheft 19), Berger & Söhne, Vienna, 2012. ISSN 1993-1271 (false ISSN-number, correct ISSN 1993-1255). p. 27.

- Otto Antonia Graf: Otto Wagner. Band 1: Das Werk des Architekten 1860–1902. 2nd edn., Böhlau, Vienna etc., 1994, ISBN 3-205-98224-X, S. 253 (Schriften des Instituts für Kunstgeschichte. Akademie der Bildenden Künste Wien. 2, 1).

- Wien seit 60 Jahren. Zur Erinnerung an die Feier der 60jährigen Regierung Seiner Majestät des Kaisers Franz Josef I. der Jugend Wiens gewidmet von dem Gemeinderate ihrer Heimatstadt. Gerlach & Wiedling, Vienna, 1908, p. 27.

Literature

- Ingrid Mader, Der Wiener Linienwall aus historischer, topographischer und archäologischer Sicht, in: Fundort Wien 14, 2011 (2011) 144-163.

- Ingrid Mader, Ingeborg Gaisbauer, Werner Chmelar: Der Wiener Linienwall. Vom Schutzbau zur Steuergrenze. Wien Archäologisch 9. Stadtarchäologie Wien, Vienna, 2012, ISBN 978-3-85161-064-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Linienwall. |

- Wiener Zeitung – Der Vorläufer des Gürtels (version from the Internet Archive, as the original is no longer available)

- Wieden Provincial Museum – the Linienwall auf der Wieden

- Course of the Linienwall around Vienna, ca. 1850 (version from the Internet Archive, as the original is no longer available)