Lionel Groulx

Lionel Groulx (French pronunciation: [ɡʁu]; 13 January 1878 – 23 May 1967) was a Canadian Roman Catholic priest, historian, and Quebec nationalist.[1]

The Reverend Lionel Groulx | |

|---|---|

Lionel-Adolphe Groulx photo from ca. 1925–1935 | |

| Church | Latin Church |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 13, 1878 Vaudreuil, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | May 23, 1967 (aged 89) Vaudreuil, Quebec, Canada |

| Nationality | Canadian |

Biography

Early life and ordination

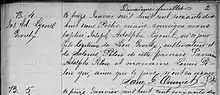

Lionel Groulx, né Joseph Adolphe Lyonel Groulx, the son of a farmer and lumberjack, and direct descendant[2] of New France pioneer Jean Grou, was born and died at Vaudreuil, Quebec. After his seminary training and studies in Europe, he taught at Valleyfield College in Salaberry-de-Valleyfield, and then the Université de Montréal. In 1917 he co-founded a monthly journal called Action Française, becoming its editor in 1920.

Study of Confederation

Groulx was one of the first Quebec historians to study Confederation: he insisted on its recognition of Quebec rights and minority rights, although he believed a combination of corrupt political parties and French Canadian minority status in the Dominion had failed to deliver on those promises, as the Manitoba conflict exposed. Groulx believed that only through national education and the Quebec government could the economic and social inferiority of French Canadians be repaired. Groulx was quite successful promoting his brand of ultramontanism.

His main focus was to restore Quebeckers' pride in their identity by knowledge of history, both the heroic acts of New France and the French Canadian and self-government rights obtained through a succession of important political victories: 1774, the Quebec Act recognized the rights of the Quebec province and its people with respect to French law, Catholic religion and the French language; in 1848, responsible government was finally obtained after decades of struggle, along with the rights of the French language; in 1867, the autonomy of the province of Quebec was restored as Lower Canada was an essential partner in the creation of a new Dominion through Confederation [La Confédération canadienne, Montréal, Quebec 10/10, 1978 (1918)].

Lionel Groulx called the Canadian Confederation of 1867 a failure and espoused the theory that French Canada's only hope for survival was to bolster a French State and a Roman Catholic Quebec as the means to emancipate the nation and a bulwark against English power. He believed the powers of the provincial government of Quebec could and should be used, within Confederation, to better the lot of the French Canadian nation, economically, socially, culturally and linguistically.

His curriculum and writings de-emphasized or ignored conflicts between the clergy and those who were struggling for democratic rights, and de-emphasized any conflicts between the "habitants" or peasant class and the French-Canadian elites. He preferred the settled habitants to the more adventurous and, in his view, licentious coureurs des bois. His work, under the pseudonym Lionel Montal, was part of the literature event in the art competition at the 1924 Summer Olympics.[3]

In 1928, the Université de Montréal insisted that Groulx sign a paper saying that he would respect Confederation and English-Canadian sensibilities as a condition of receiving a respectable salary for his teaching work. He would not sign, but finally agreed to a condition that he would limit himself to historical studies; he resigned from the editorship of L'action canadienne-française soon after, and the magazine ceased publication at the end of the year.[4]

Lionel Groulx's major writings include L'Appel de la race (1922), Histoire de la Confédération, Notre grande aventure, Histoire du Canada français (1951), and Notre maître le passé.

Writings on New France

In order to inculcate such pride in a nation he considered degraded by Conquest, he engaged in national myth-making, celebrating the days of New France as a golden age and elevating Dollard des Ormeaux into a legendary hero. He has been described as the first French Canadian historian to consider the period of the French regime superior to that of the English rule that followed it, evaluating the Conquest as a disaster rather than the common nineteenth century view of it as a blessing that saved Quebec from the atheist terror of the French Revolution.[5]

He also developed a Quebec history curriculum that emphasized the heroism of New France, the challenge British Conquest posed to the survival of the "Canadiens", and how this challenge was met by lengthy political struggles for democratic rights. He particularly insisted, as had many before him, on the Quebec Act of 1774 as the official recognition of his nation's rights. He bore particular affection for the undertaking of Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, that in 1849 successfully restored the rights of the French language along with the obtention of responsible government, thus thwarting the assimilation plans of Lord Durham's policy of forced Union between Upper and Lower Canada. (See Lord Elgin)

Ligue d'action française

At the Ligue d'Action française, Groulx and his colleagues hoped to inspire revival of the French language and French Canadian culture, but also to create a think tank and public space of reflection, so that the French Canadian nation's elites would find ways to remedy French Canada's underdevelopment and exclusion from big business.

Some collaborators of the review thus actively participated in the development of the HEC business school. Others were actively involved in the promotion of the Church's Social doctrine, an official Catholic answer to socio-economic distress that was meant to prevent the appeal of socialism and improve capitalism.

Groulx's conservative Catholicism was not very appreciative of other religions, although he also acknowledged that racism was not Christian, and he maintained that Quebec should aspire to be a model society by Christian standards, including intense missionary action. [Le Canada français missionnaire, Montreal, Fides, 1962].

Catholic social teaching

This Catholic social doctrine later became part of the 1930s Action liberale nationale (ALN) party, a new party that intellectuals close to Groulx and the defunct Action française appreciated. When Maurice Duplessis's victory became apparent, some instead accepted to cooperate with his government and its reforms. But Groulx, and with him a large number of intellectuals, chose to oppose him.

During the Second World War Groulx, like many Canadien nationalists, spoke in favour of the Vichy regime of Philippe Pétain, although public statements to this effect remained rare.[6]

Groulx and other intellectuals settled into a partial alliance with Liberal Party of Quebec leader Adelard Godbout, who served as Premier from 1939 to 1944. They soon broke with him on account of his submission to the federal Liberals. Yet in 1944 they opposed Duplessis again, this time placing their hopes in another new party, the Bloc populaire Canadien, led by André Laurendeau. Future Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau was part of this young party, which soon suffered the same fate as the previous third party, the ALN. After the 1948 election, the Bloc populaire Canadien disappeared.

Economic protectionism

Groulx was later remembered both for his strong case in favour of economic reconquest of Quebec by French Canadians, defense of the French language, and pioneer work as the first chair of Canadian history in Quebec (Universite de Montreal; see Ronald Rudin, Making History in Twentieth Century Quebec, Toronto University Press, 1997). Rudin underscores Groulx's founding role in scholarly History with the development of the Montréal History Department. Groulx founded the Institut d'histoire d'Amérique française in 1946, an institute located in Montreal devoted to the historical study of Quebec and of the French presence in the Americas and the publication of La revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, still today arguably the main publication for professional historians in Quebec. His main intellectual contribution was to create a rapprochement between nationalism and the Catholic religion, blunting the hostility between them that had existed in the nineteenth century.

Later influence

Through his writings and teaching at the university and his association with the intellectual elite of Quebec, he had a profound influence on many people (such as Michel Chartrand and Camille Laurin). However, many of the young intellectuals he influenced often did not share his conservative ideology (such as his successor at the University of Montreal). Groulx's traditionalist, religious form of Québécois nationalism, known as clerico-nationalism, influenced Quebec society into the 1950s.

Collège Lionel-Groulx, Lionel Groulx Avenue and the Lionel Groulx metro station are named in his honour.

In June 2020, in the wake of global anti-racism and anti-police brutality protests, a petition is being circulated by Montréalers asking the city government to rename the Lionel-Groulx métro station after the African-Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson.[7][8] A counter petition is also circulating, asking Montreal to retain the name.

Accusations of anti-Semitism

Accusations of anti-Semitism were made by Canadian author Mordecai Richler and French-Canadian historian Esther Delisle in the 1990s against several pre-World War II Quebec intellectuals, including Groulx.[9]

In 1933, writing under the pseudonym Jacques Brassier in the article "So That We May Live..." [Pour qu'on vive..."], published in the journal L'Action nationale [National Action], Groulx states his opposition to anti-Semitism. In the section "The Jewish Problem" [Le problème juif], he states, "Antisemitism is not only not a Christian solution [to the Jewish problem], it is a solution that is negative and ridiculous." ["L'antisémitisme, non seulement n'est pas une solution chrétienne; c'est une solution négative et niaise"] (trans. Robinson 101).[10] Apologists for Groulx have cited that quotation.[11] However, the following sentence of the article has Groulx go on to give his unequivocal support to the boycott of Jewish businesses in Quebec: "To resolve the Jewish problem, it would suffice if French Canadians regained their common sense. There is no need of extraordinary legislation; no need for violence of any sort. We will only give our people the order, 'Do not buy from the Jews'.... And if by some miracle our order were understood and complied with, then in six months the Jewish problem would be solved, not merely in Montréal but from one end of the province to the other" (trans. Robinson 101-102). Thus, put into context, although he stops short of advocating the legislation of outright anti-Semitic policies and supporting violence against Jews, Groulx supported systemic anti-Semitism by giving French Canadians the "order" to boycott Jewish businesses to solve the "Jewish problem" in Quebec.

Citing Groulx's assertion that anti-Semitism is "negative and ridiculous," some scholars have downplayed allegations of anti-Semitism against Groulx. In a speech given in 1999, the historian Xavier Gélinas argues that Groulx did not support "racial anti-Semitism," which "confronts Jews for being Jews." While acknowledging the problematic and anti-Semitic nature of Groulx's rhetoric, Gélinas claims that it represents "cultural anti-Semitism" that singles out Jews because of the "principles and customs that they are deemed, rightly or wrongly, to believe in and to practice" and are "opposed to the traditional nationalist vision of Quebec."[12]

References

- "Canadian Encyclopedia".

- "L. Groulx, Notre maître, le passé, 1924, pp. 71-76". Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Lionel Groulx". Olympedia. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Mason Wade, The French-Canadians 1760–1967, vol. 2, p. 894.

- Olivar Asselin, ..L'Oeuvre de l'abbé Groulx.., 1929.

- Lionel Groulx, Constantes de vie (Montréal: Fides, 1967), p. 111 and Éric Amyot, Le Québec entre Pétain et de Gaulle: Vichy, la France libre et les Canadiens Français, p. 173 (Editions Fides, 1999)

- Mignacca, Franca (20 June 2020). "Montrealers call for Lionel-Groulx Metro station to be renamed after Oscar Peterson". CBC News. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "This is why Montreal wants to rename a subway station after Oscar Peterson". www.freshdaily.ca. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- Robinson, Ira (2013). "Reflections on Antisemitism in French Canada". Canadian Jewish Studies. 21. ISSN 1916-0925.

- Brassier, Jacques (April 1933). "Pour qu'on vive..." L'Action Nationale: 238–247 – via BANQ.

- Caldwell, Gary. "The Sins of the Abbé Groulx". Literary Review of Canada. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Gélinas, Xavier (1998). "Notes on Anti-Semitism Among Quebec Nationalists, 1920-1970: Methodological Failings, Distorted Conclusions".

Further reading

- Beaudreau, Sylvie. "Déconstruire le rêve de nation: Lionel Groulx et la Révolution tranquille." Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française 56#1 (2002): 29-61.

- Frégault, Guy. Lionel Groulx tel qu’en lui-même (Leméac, 1978)

- Gagnon, Serge. Quebec and Its Historians: 1840 To 1920 (1981)

- Senese, Phyllis M. "Catholique d'abord: Catholicism and Nationalism in the Thought of Lionel Groulx." Canadian Historical Review 60#2 (1979): 154-177.

Primary sources

- Trofimenkoff, Susan Mann, ed. Abbé Groulx: Variations on a Nationalist Theme (1973), 256pp; 15pp introduction followed by long extracts in English translation

External links

- Bibliography on Lionel Groulx

- Groulx ancestral-historical memoirs, family Grou

- Several texts on or about Groulx including a substantial text on the historiographical debate on the charges of Anti-Semitism made against Lionel Groulx

- Notes on Anti-Semitism Among Quebec Nationalists, 1920-1970. Methodological Failings. Distorted Conclusions