List of mammoth specimens

List of notable individual fossil or subfossil mammoth remains

| Name | Image | Location of discovery | Date of discovery | Age of remains in radiocarbon years BP |

Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

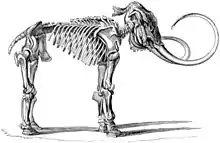

| Adams mammoth |  |

Mouth of the Lena River, Siberia[1] | 1799[1][2] | 35,800±1200[1][3] | It is the first complete mammoth skeleton ever to be reconstructed. Originally, it was an entire mummified mammoth carcass.[2] |

| Beresovka Mammoth |  |

Berezovka River, Siberia[4] | 1900[4] | 44,000±3,500[4] | Except for head, it is an almost wholly preserved, mummified mammoth carcass.[4] |

| Fairbanks Creek Mammoth (Effie)[5] | Fairbanks Creek near Fairbanks, Alaska[5] | 1948[5] | 21,300±1,300[5][6] | It consists of the mummified head, trunk, and left forelimb of a mammoth calf. It was recovered from muck near prehistoric scraper.[5] | |

| Fishhook Mammoth[7] | Shoreline banks of the estuary of the Upper Taimyra River, Taymyr Peninsula, Siberian Federal District.[7] | 1990-1992[7] | 20,620±70[7] | Partial woolly mammoth carcass[7] | |

| Jarkov Mammoth[8][9] | Taymyr Peninsula, Siberian Federal District[9][8] | July 1997[8] | 20,390±160[8] | Found by members of the Jarkov family, who are Dolgan reindeer herders.[8] | |

| Kirgilyakh (Magadan) Mammoth (Dima)[8][10] |  |

Northeast Siberia, near Kirgilyakh Creek in the Upper Kolyma basin[8][10] | June 23, 1977[10] | 41,000±900[10] | The discovery of the frozen carcass of the Kirgilyakh (Magadan) Mammoth or Dima provided the first opportunity for a detailed study of the anatomy of a mammoth calf.[10] |

| Lyuba Mammoth[11][12] |  |

Near the Yuribei River on the Yamal Peninsula in northwest Siberia.[11][12] | May 2007[11] | 41,700+700/-550[11] | Lyuba is regarded to be the most complete and best-preserved mammoth calf discovered. It is nicknamed Lyuba after the diminutive of the name of the wife of the reindeer herder who discovered it.[11][12] |

| Malolyakhovsky Mammoth[13] Buttercup[14] | Maly Lyakhovsky Island of the New Siberian Islands archipelago[13] | 2012[13] | 28,610±110[13] | While many mammoths found in permafrost are dried up and mummified, “this was really juicy,” said Herridge, who likened the appearance of the muscle to a “piece of steak — bright red when you cut into the flesh and then as it hit the air, it would go brown.”[15] | |

| Yuka Mammoth[16][17] |  |

Oyagossky Yar coast, 30 km west from the mouth of the Kondratieva River near Yukagir, Siberia.[17] | August 2010[17] | 34,300+260/−240[17] | The Yuka mammoth corpse consists of about 95% of its hide, and soft tissues around limbs were preserved in articulated position. This female mammoth calf was nicknamed ‘Yuka’ after the village of Yukagir, whose local people discovered it.[16][17] |

| Sopkarga Mammoth (Zhenya)[18][19] | Taymyr Peninsula, Siberian Federal District[18] | August 28, 2012[18][19] | 43,350±240[19] | The Sopkarga Mammoth (Zhenya) was found on the right bank of the Yenisei River about 3 km north of the Sopochnaya Karga Meteorological Station on Sopochnaya Karga Cape. Zhenya is the diminutive of the name of the 11-year-old boy who discovered it.[18][19] | |

| Khroma Mammoth[20] | Allaikhovskii District, Yakutia, Khroma River[20] | October 2008[20] | greater than 45,000[21] | Khroma is very well preserved excepting the absence of trunk.[20] | |

| Yukagir mammoth |  |

Northern Yakutia, Arctic Siberia, Russia | Autumn of 2002 | 22,500 cal. BP [22] | Notably well-preserved head, which revealed that woolly mammoths had temporal glands between the ear and the eye[22] |

List of significant fossil or subfossil mammoth bone accumulations

| Name | Image | Location of discovery | Date of discovery | Age of remains in years BP | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Achchagyi–Allaikha mass accumulation[23][24] | Achchagyi–Allaikha stream, Yana-Indighirka coastal lowlands, Siberia.[24][25] | 1987[24] | 12,490±80 to 12,400±60 BP., C14[24] | The concentration of bones in the Achchagyi–Allaikha mass accumulation was likely result from the simultaneous deaths of a large number of animals within herd-family groups in one or several seasons. The formation of this mass accumulation is argued to be a direct consequence of short but strong climatic warming (Bølling oscillation) and associated unfavorable environmental conditions.[24] | |

| Berelyokh mass accumulation[23][24][25] | Byoryolyokh River, Yana-Indighirka coastal lowlands, Siberia.[24][25] | 1947[25] | 12,720±100 to 11,900±50 BP., C14[24] | The concentration of bones in the Berelyokh mass accumulation was likely result from the simultaneous deaths of a large number of animals within herd-family groups in one or several seasons. The formation of this mass accumulation is argued to be a direct consequence of short but strong climatic warming (Bølling oscillation) and associated unfavorable environmental conditions.[24][25] | |

| Condover site[26] | Norton Farm Pit, Condover, south of Shrewsbury, United kingdom[26] | 1986[26] | circa 12,300 BP., C14, Greenland Interstadial 1[26] | Remains of several mammoths trapped in glacial kettle-hole[26] | |

| The Mammoth Site[27] |  |

Hot Springs, South Dakota[27][28][29] | 1974[27][28] | Greater than 26,000 B.P, C14[29] | As of 2016, the remains of 58 North American Columbian and 3 woolly mammoths have been found within pond sediments filling an ancient sinkhole.[28][29] |

| Waco Mammoth National Monument[30][31] |  |

Waco, Texas[30] | 1978[30] | 66,800±5,000 BP, calendar[32] | As of 2016, two bone beds have yielded 25 Columbian mammoths, a western camel, a saber-toothed cat, a coyote, a dwarf pronghorn, a bison, a horse, a peccary, an American alligator, a tortoise, various freshwater turtles, freshwater drum, and gar.[31] |

References

- Iacumin, P., Davanzo, S. and Nikolaev, V., 2006. Spatial and temporal variations in the 13 C/12 C and 15 N/14 N ratios of mammoth hairs: palaeodiet and palaeoclimatic implications. Chemical Geology, 231(1), pp.16-25.

- Cohen, C., 2002. The Fate of the Mammoth: Fossils, Myth, and History. University of Chicago Press. 336 pp. ISBN 978-0226112923

- Bishop, S., and Burns, P., 1998-2016, Mammoths: Evidence of Catastrophe? TalkOrigins Archive. Access Date October 2, 2017

- Ukraintseva, V.V., Agenbroad, L.D., Mead, J.I. and Hevly, R.H., 1993. Vegetation cover and environment of the "Mammoth Epoch," Siberia. The Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, Rapid City, South Dakota.

- Dixon, J.E., 1999. Bones, Boats, & Bison: Archaeology and the First Colonization of Western North America. University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. 322 pp.

- Farrand, W.R., 1961. Frozen mammoths and modern geology. Science, pp. 729-735.

- Mol, D., Tikhonov, A.N., MacPhee, R.D.E., Flemming, C., Buigues, B., De Marliave, C., Coppens, Y. and Agenbroad, L.D., 2001. The Fishhook Mammoth: rediscovery of a woolly mammoth carcass by the CERPOLEX/Mammuthus Team, Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia. In Proceedings of the 1st International Congress La Terra degli Elefanti/The World of Elephants, Rome (pp. 310-313).

- Ukraintseva, V.V., 2013. Mammoths and the Environment. Cambridge University Press. 354 pp. ISBN 978-1-10702-716-9

- Mol, D., Coppens, Y., Tikhonov, A.N., Agenbroad, L.D., MacPhee, R.D.E., Flemming, C., Greenwood, A., Buigues, B., De Marliave, C., Van Geel, B. and Van Reenen, G.B.A., 2001. The Jarkov Mammoth: 20,000-year-old carcass of a Siberian woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius (Blumenbach, 1799). In Proceedings of the 1st International Congress’ The World of Elephants ‘(Roma) pp. 305-309.

- Lozhkin, A.V. and Anderson, P.M., 2016. About the age and habitat of the Kirgilyakh mammoth (Dima), Western Beringia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 145, pp.104-116.

- Fisher, D.C., Tikhonov, A.N., Kosintsev, P.A., Rountrey, A.N., Buigues, B. and van der Plicht, J., 2012. Anatomy, death, and preservation of a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) calf, Yamal Peninsula, northwest Siberia. Quaternary International, 255, pp.94-105.

- Papageorgopoulou, C., Link, K. and Rühli, F.J., 2015. Histology of a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) preserved in permafrost, Yamal Peninsula, northwest Siberia. The Anatomical Record, 298(6), pp.1059-1071.

- Grigoriev, S.E., Fisher, D.C., Obadă, T., Shirley, E.A., Rountrey, A.N., Savvinov, G.N., Garmaeva, D.K., Novgorodov, G.P., Cheprasov, M.Y., Vasilev, S.E. and Goncharov, A.E., 2017. A woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) carcass from Maly Lyakhovsky Island (New Siberian Islands, Russian Federation). Quaternary International. 445, pp.98-103.

- Ghose, T., 2014. Fresh Mammoth Carcass from Siberia Holds Many Secrets. Scientific American. Access Date October 2, 2017

- Emily Chung (November 26, 2014). "Woolly mammoth 'autopsy' provides flesh and blood samples". CBC News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

The well-preserved mammoth, nicknamed Buttercup, was discovered buried in the ice on Maily Lyakhovsky Island in May 2013.

- Boeskorov, G.G., Potapova, O.R., Mashchenko, E.N., Protopopov, A.V., Kuznetsova, T.V., Agenbroad, L. and Tikhonov, A.N., 2014. Preliminary analyses of the frozen mummies of mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), bison (Bison priscus) and horse (Equus sp.) from the Yana‐Indigirka Lowland, Yakutia, Russia. Integrative zoology, 9(4), pp.471-480.

- Rudaya, N., Protopopov, A., Trofimova, S., Plotnikov, V. and Zhilich, S., 2015. Landscapes of the ‘Yuka’mammoth habitat: A palaeobotanical approach. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 214, pp.1-8.

- Maschenko, E.N., Tikhonov, A.N., Serdyuk, N.V., Tarasenko, K.K. and Lopatin, A.V., 2015. A finding of the male mammoth carcass in the Karginsky suit of the Upper Pleistocene of the Taimyr Peninsula. In Doklady Biological Sciences, 460, no. 1, p.32-35.

- Maschenko, E.N., Potapova, O.R., Vershinina, A., Shapiro, B., Streletskaya, I.D., Vasiliev, A.A., Oblogov, G.E., Kharlamova, A.S., Potapov, E., van der Plicht, J. and Tikhonov, A.N., 2017. The Zhenya Mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius (Blum.)): Taphonomy, geology, age, morphology and ancient DNA of a 48,000 year old frozen mummy from western Taimyr, Russia. Quaternary International, 445, pp.104-134.

- Lacombat, F., Tikhonov, A.N., Cortella, L., Fisher, D.C., Buigues, B. and Lazarev, P., 2016. Khroma: autopsy of a story. Bull. Mus. Préhist. Monacco, suppl, (6), pp.149-154.

- Fisher, D.C., Shirley, E.A., Whalen, C.D., Calamari, Z.T., Rountrey, A.N., Tikhonov, A.N., Buigues, B., Lacombat, F., Grigoriev, S. and Lazarev, P.A., 2014. X-ray computed tomography of two mammoth calf mummies X-Ray CT of Mammoth Calves. Journal of Paleontology, 88(4), pp.664-675

- Mol, Dick; Shoshani, Jeheskel (Hezy); Tikhonov, Aleksei; GEEL, Bas van; Lazarev, Peter; Boeskorov, Gennady; Agenbroad, Larry (2006). "The Yukagir Mammoth: Brief History, 14c dates, individual age, gender, size, physical and environmental conditions and storage" (PDF). Scientific Annals, School of Geology Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (AUTH). 98: 299–314. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- In the former Soviet Union and Russia, bone beds and other accumulations of fossil and subfossil bones are known in the scientific literature as mass accumulations.

- Nikolskiy, P.A., Basilyan, A.E., Sulerzhitsky, L.D. and Pitulko, V.V., 2010. Prelude to the extinction: revision of the Achchagyi–Allaikha and Berelyokh mass accumulations of mammoth. Quaternary International, 219(1), pp. 16-25.

- Leshchinskiy, S.V., 2017. Strong evidence for dietary mineral imbalance as the cause of osteodystrophy in Late Glacial woolly mammoths at the Berelyokh site (Northern Yakutia, Russia). Quaternary International, 30, p.1e25.

- Scourse, J.D., Coope, G.R., Allen, J.R.M., Lister, A.M., Housley, R.A., Hedges, R.E.M., Jones, A.S.G. and Watkins, R., 2009. Late‐glacial remains of woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) from Shropshire, UK: stratigraphy, sedimentology and geochronology of the Condover site. Geological Journal, 44(4), pp. 392-413.

- Agenbroad, L.D., 1994. Geology, hydrology, and excavation of the site. In Agenbroad, L.D. and Mead, J.I., eds., pp. 15-27. “The Hot Springs Mammoth Site: A Decade of Field and Laboratory Research in the Paleontology, Geology, and Paleoecology.” The Mammoth Site of South Dakota. Inc. Hot Springs, South Dakota.

- Laury, R.L., 1980. Paleoenvironment of a late Quaternary mammoth-bearing sinkhole deposit, Hot Springs, South Dakota. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 91(8), pp.465-475.

- Mahan, S.A., Hanson, P.R., Mead, J., Holen, S., and Wilkins, J., 2016. Dating the Hot Springs, South Dakota Mammoth Sinkhole Site. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 48:7. doi: 10.1130/abs/2016AM-281798

- Bongino, J.D., 2007. Late quaternary history of the Waco Mammoth site: environmental reconstruction and interpreting the cause of death (Doctoral dissertation).

- Wiest, L.A., Esker, D. and Driese, S.G., 2016. The Waco Mammoth National Monument May Represent a Diminished Watering-Hole Scenario Based on Preliminary Evidence of Post-Mortem Scavenging. Palaios, 31(12), pp.592-606.

- Nordt, L., Bongino, J., Forman, S., Esker, D. and Benedict, A., 2015. Late Quaternary environments of the Waco Mammoth site, Texas USA. Quaternary Research, 84(3), pp. 423-438.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.