Luxembourg

Luxembourg (/ˈlʌksəmbɜːrɡ/ (![]() listen) LUK-səm-burg;[8] Luxembourgish: Lëtzebuerg [ˈlətsəbuːə̯ɕ] (

listen) LUK-səm-burg;[8] Luxembourgish: Lëtzebuerg [ˈlətsəbuːə̯ɕ] (![]() listen); French: Luxembourg; German: Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg,[lower-alpha 3] is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France to the south. Its capital, Luxembourg City,[9] is one of the four official capitals of the European Union (together with Brussels, Frankfurt, and Strasbourg) and the seat of the Court of Justice of the European Union, the highest judicial authority in the EU.[10] Its culture, people, and languages are highly intertwined with its neighbours, making it a mixture of French and German cultures. It has three official languages: French, German, and the national language of Luxembourgish.[11]

listen); French: Luxembourg; German: Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg,[lower-alpha 3] is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France to the south. Its capital, Luxembourg City,[9] is one of the four official capitals of the European Union (together with Brussels, Frankfurt, and Strasbourg) and the seat of the Court of Justice of the European Union, the highest judicial authority in the EU.[10] Its culture, people, and languages are highly intertwined with its neighbours, making it a mixture of French and German cultures. It has three official languages: French, German, and the national language of Luxembourgish.[11]

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

| |

|---|---|

Motto: "Mir wëlle bleiwe wat mir sinn" (Luxembourgish) "Nous voulons rester ce que nous sommes" (French) "Wir wollen bleiben, was wir sind" (German) "We want to remain what we are" | |

Royal anthem: "De Wilhelmus"a | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Luxembourg City[1] 49°48′52″N 06°07′54″E |

| Official languages | |

| Nationality (2017) |

|

| Religion (2018[2]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Luxembourger |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

| Henri | |

• Prime Minister (list) | Xavier Bettel |

| Legislature | Chamber of Deputies |

| Independence | |

| 15 March 1815 | |

• Independence in personal Union with the Netherlands (Treaty of London) | 19 April 1839 |

• Reaffirmation of Independence Treaty of London | 11 May 1867 |

| 23 November 1890 | |

• from the Greater German Reich | 1944 / 1945 |

• Admitted to the United Nations | 24 October 1945 |

| 1 January 1958 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,586.4 km2 (998.6 sq mi) (167th) |

• Water (%) | 0.23 (as of 2015)[3] |

| Population | |

• January 2020 estimate | |

• 2011 census | 512,353 |

• Density | 242/km2 (626.8/sq mi) (58th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | medium · 19th |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 23rd |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Note: Although Luxembourg is located in Western European Time/UTC (Z) zone, since 1 June 1904, LMT (UTC+0:24:36) was abandoned and Central European Time/UTC+1 was adopted as standard time, with a +0:35:24 offset (+1:35:24 during DST) from Luxembourg City’s LMT. | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +352 |

| ISO 3166 code | LU |

| Internet TLD | .lub |

| |

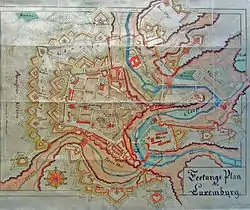

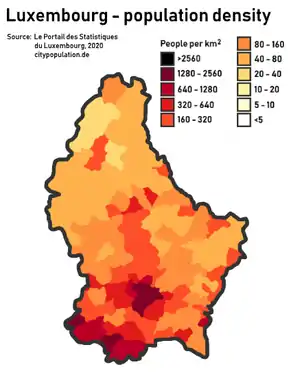

With an area of 2,586 square kilometres (998 sq mi), it is one of the smallest sovereign states in Europe.[12] In 2019, Luxembourg had a population of 626,108, which makes it one of the least-populous countries in Europe,[13] but by far the one with the highest population growth rate.[14] Foreigners account for nearly half of Luxembourg's population.[15] As a representative democracy with a constitutional monarch, it is headed by Grand Duke Henri and is the world's only remaining sovereign grand duchy. Luxembourg is a developed country, with an advanced economy and one of the world's highest GDP (PPP) per capita. The City of Luxembourg with its old quarters and fortifications was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994 due to the exceptional preservation of the vast fortifications and the old city.[16]

The history of Luxembourg is considered to begin in 963, when count Siegfried acquired a rocky promontory and its Roman-era fortifications known as Lucilinburhuc, "little castle", and the surrounding area from the Imperial Abbey of St. Maximin in nearby Trier.[17][18] Siegfried's descendants increased their territory through marriage, war and vassal relations. At the end of the 13th century, the counts of Luxembourg reigned over a considerable territory.[19] In 1308, Count of Luxembourg Henry VII became King of the Germans and later Holy Roman Emperor.[20] The House of Luxembourg produced four emperors during the High Middle Ages. In 1354, Charles IV elevated the county to the Duchy of Luxembourg.[21] The duchy eventually became part of the Burgundian Circle and then one of the Seventeen Provinces of the Habsburg Netherlands.[22] Over the centuries, the City and Fortress of Luxembourg, of great strategic importance situated between the Kingdom of France and the Habsburg territories, was gradually built up to be one of the most reputed fortifications in Europe. After belonging to both the France of Louis XIV and the Austria of Maria Theresa, Luxembourg became part of the First French Republic and Empire under Napoleon.[23]

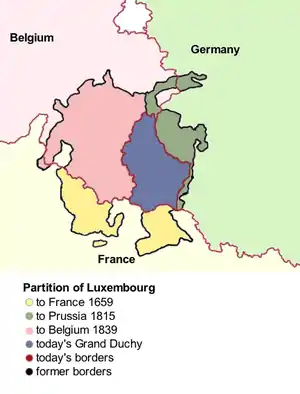

The present-day state of Luxembourg first emerged at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The Grand Duchy, with its powerful fortress, became an independent state under the personal possession of William I of the Netherlands with a Prussian garrison to guard the city against another invasion from France.[24][25] In 1839, following the turmoil of the Belgian Revolution, the purely French-speaking part of Luxembourg was ceded to Belgium and the Luxembourgish-speaking part (except the Arelerland, the area around Arlon) became what is the present state of Luxembourg.[26]

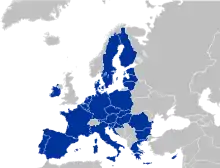

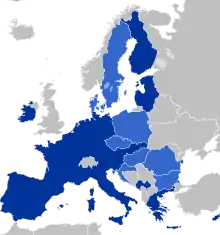

Luxembourg is a founding member of the European Union,[27] OECD, United Nations, NATO, and Benelux.[28][29] The city of Luxembourg, which is the country's capital and largest city, is the seat of several institutions and agencies of the EU.[30] Luxembourg served on the United Nations Security Council for the years 2013 and 2014, which was a first in the country's history.[31] As of 2020, Luxembourg citizens had visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to 187 countries and territories, ranking the Luxembourgish passport fifth in the world, tied with Denmark and Spain.[32]

History

County

The recorded history of Luxembourg begins with the acquisition of Lucilinburhuc[34] (today Luxembourg Castle) situated on the Bock rock by Siegfried, Count of Ardennes, in 963 through an exchange act with St. Maximin's Abbey, Trier.[35] Around this fort, a town gradually developed, which became the centre of a state of great strategic value.

Duchy

In the 14th and early 15th centuries, three members of the House of Luxembourg reigned as Holy Roman Emperors. In 1437, the House of Luxembourg suffered a succession crisis, precipitated by the lack of a male heir to assume the throne, which led to the territories being sold by Duchess Elisabeth to Philip the Good of Burgundy.[36]

In the following centuries, Luxembourg's fortress was steadily enlarged and strengthened by its successive occupants, the Bourbons, Habsburgs, Hohenzollerns and the French.

Nineteenth century

After the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, Luxembourg was disputed between Prussia and the Netherlands. The Congress of Vienna formed Luxembourg as a Grand Duchy within the German Confederation. The Dutch king became, in personal union, the grand duke. Although he was supposed to rule the grand duchy as an independent country with an administration of its own, in reality he treated it similarly to a Dutch province. The Fortress of Luxembourg was manned by Prussian troops for the German Confederation.[37] This arrangement was revised by the 1839 First Treaty of London, from which date Luxembourg's full independence is reckoned.[38][39][40][41]

At the time of the Belgian Revolution of 1830–1839, and by the 1839 Treaty establishing full independence, Luxembourg's territory was reduced by more than half, as the predominantly francophone western part of the country was transferred to Belgium. In 1842 Luxembourg joined the German Customs Union (Zollverein).[42][43] This resulted in the opening of the German market, the development of Luxembourg's steel industry, and expansion of Luxembourg's railway network from 1855 to 1875, particularly the construction of the Luxembourg-Thionville railway line, with connections from there to the European industrial regions.[44] While Prussian troops still manned the fortress, in 1861, the Passerelle was opened, the first road bridge spanning the Pétrusse river valley, connecting the Ville Haute and the main fortification on the Bock with Luxembourg railway station, opened in 1859, on the then fortified Bourbon plateau to the south.

After the Luxembourg Crisis of 1866 nearly led to war between Prussia and France, the Grand Duchy's independence and neutrality were again affirmed by the 1867 Second Treaty of London, Prussia's troops were withdrawn from the Fortress of Luxembourg, and its Bock and surrounding fortifications were dismantled.[45]

The King of the Netherlands remained Head of State as Grand Duke of Luxembourg, maintaining a personal union between the two countries until 1890. At the death of William III, the throne of the Netherlands passed to his daughter Wilhelmina, while Luxembourg (then restricted to male heirs by the Nassau Family Pact) passed to his third cousin, Adolph of Nassau-Weilburg.[46]

At the time of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870, despite allegations about French use of the Luxembourg railways for passing soldiers from Metz (then part of France) through the Duchy, and for forwarding provisions to Thionville, Luxembourg's neutrality was respected by Germany, and neither France nor Germany invaded the country.[47][48] But in 1871, as a result of Germany's victory over France, Luxembourg's boundary with Lorraine, containing Metz and Thionville, changed from being a frontier with a part of France to a frontier with territory annexed to the German Empire as Alsace-Lorraine under the Treaty of Frankfurt. This allowed Germany the military advantage of controlling and expanding the railways there.

Twentieth century and beyond

In August 1914, Imperial Germany violated Luxembourg's neutrality in the war by invading it in the war against France. This enabled Germany to use the railway lines, while at the same time denying them to France. Nevertheless, despite the German occupation, Luxembourg was allowed to maintain much of its independence and political mechanisms.

In 1940, after the outbreak of World War II, Luxembourg's neutrality was again violated when the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany entered the country, "entirely without justification".[49] In contrast to the First World War, under the German occupation of Luxembourg during World War II, the country was treated as German territory and informally annexed to the adjacent province of the Third Reich, Moselland. A government in exile based in London supported the Allies, sending a small group of volunteers who participated in the Normandy invasion. Luxembourg was liberated in September 1944, and became a founding member of the United Nations in 1945. Luxembourg's neutral status under the constitution formally ended in 1948, and in 1949 it became a founding member of NATO.

In 1951, Luxembourg became one of the six founding countries of the European Coal and Steel Community, which in 1957 would become the European Economic Community and in 1993 the European Union. In 1999 Luxembourg joined the Eurozone. In 2005, a referendum on the EU treaty establishing a constitution for Europe was held.[28][29]

The steel industry exploiting the Red Lands' rich iron-ore grounds in the beginning of the 20th century drove the country's industrialisation. After the decline of the steel industry in the 1970s, the country focused on establishing itself as a global financial centre and developed into the banking hub it is reputed for. Since the beginning of the 21st century, its governments have focused on developing the country into a knowledge economy, with the founding of the University of Luxembourg and a national space programme, projecting the first involvement in a robotic lunar expedition by 2020.[50]

Government and politics

Luxembourg is described as a "full democracy",[51] with a parliamentary democracy headed by a constitutional monarch. Executive power is exercised by the grand duke and the cabinet, which consists of several other ministers.[52] The Constitution of Luxembourg, the supreme law of Luxembourg, was adopted on 17 October 1868.[53] The grand duke has the power to dissolve the legislature, in which case new elections must be held within three months. However, since 1919, sovereignty has resided with the nation, exercised by the grand duke in accordance with the Constitution and the law.[54]

Legislative power is vested in the Chamber of Deputies, a unicameral legislature of sixty members, who are directly elected to five-year terms from four constituencies. A second body, the Council of State (Conseil d'État), composed of twenty-one ordinary citizens appointed by the grand duke, advises the Chamber of Deputies in the drafting of legislation.[55]

Luxembourg has three lower tribunals (justices de paix; in Esch-sur-Alzette, the city of Luxembourg, and Diekirch), two district tribunals (Luxembourg and Diekirch), and a Superior Court of Justice (Luxembourg), which includes the Court of Appeal and the Court of Cassation. There is also an Administrative Tribunal and an Administrative Court, as well as a Constitutional Court, all of which are located in the capital.

Administrative divisions

Luxembourg is divided into 12 cantons, which are further divided into 102 communes.[56] Twelve of the communes have city status; the city of Luxembourg is the largest.[57]

Capellen (1) - Clervaux(2) - Diekirch(3) - Echternach(4) - Esch-sur-Alzette(5) - Grevenmacher(6) - Luxembourg(7) - Mersch(8) - Redange(9) - Remich(10) - Vianden(11) - Wiltz(12)

Foreign relations

Luxembourg has long been a prominent supporter of European political and economic integration. In 1921, Luxembourg and Belgium formed the Belgium–Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU) to create a regime of inter-exchangeable currency and a common customs.[43] Luxembourg is a member of the Benelux Economic Union and was one of the founding members of the European Economic Community (now the European Union). It also participates in the Schengen Group (named after the Luxembourg village of Schengen where the agreements were signed).[29] At the same time, the majority of Luxembourgers have consistently believed that European unity makes sense only in the context of a dynamic transatlantic relationship, and thus have traditionally pursued a pro-NATO, pro-US foreign policy.

Luxembourg is the site of the Court of Justice of the European Union, the European Court of Auditors, the Statistical Office of the European Communities (Eurostat) and other vital EU organs. The Secretariat of the European Parliament is located in Luxembourg, but the Parliament usually meets in Brussels and sometimes in Strasbourg.[58]

Military

The Luxembourgish army is mostly based in its casern, the Centre militaire Caserne Grand-Duc Jean on the Härebierg in Diekirch.The general staff is based in the capital, the État-Major. [59] The army is under civilian control, with the grand duke as Commander-in-Chief. The Minister for Defence, François Bausch, oversees army operations. The professional head of the army is the Chief of Defence, who answers to the minister and holds the rank of general.

Being a landlocked country, Luxembourg has no navy. Seventeen NATO AWACS aeroplanes are registered as aircraft of Luxembourg.[60] In accordance with a joint agreement with Belgium, both countries have put forth funding for one A400M military cargo plane.[61]

Luxembourg has participated in the Eurocorps, has contributed troops to the UNPROFOR and IFOR missions in former Yugoslavia, and has participated with a small contingent in the NATO SFOR mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Luxembourg troops have also deployed to Afghanistan, to support ISAF. The army has also participated in humanitarian relief missions such as setting up refugee camps for Kurds and providing emergency supplies to Albania.[62]

Geography

Luxembourg is one of the smallest countries in Europe, and ranked 167th in size of all the 194 independent countries of the world; the country is about 2,586 square kilometres (998 sq mi) in size, and measures 82 km (51 mi) long and 57 km (35 mi) wide. It lies between latitudes 49° and 51° N, and longitudes 5° and 7° E.[63]

To the east, Luxembourg borders the German Bundesländer of Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland, and to the south, it borders the French région of Grand Est (Lorraine). The Grand Duchy borders the Belgian Walloon Region, in particular the latter's provinces of Luxembourg and Liège, part of which comprises the German-speaking Community of Belgium, to the west and to the north, respectively.

The northern third of the country is known as the Oesling, and forms part of the Ardennes. It is dominated by hills and low mountains, including the Kneiff near Wilwerdange,[64] which is the highest point, at 560 metres (1,837 ft). Other mountains are the Buurgplaatz at 559 metres near Huldange and the Napoléonsgaard at 554 metres near Rambrouch. The region is sparsely populated, with only one town (Wiltz) with a population of more than four thousand people.

The southern two-thirds of the country is called the Gutland, and is more densely populated than the Oesling. It is also more diverse and can be divided into five geographic sub-regions. The Luxembourg plateau, in south-central Luxembourg, is a large, flat, sandstone formation, and the site of the city of Luxembourg. Little Switzerland, in the east of Luxembourg, has craggy terrain and thick forests. The Moselle valley is the lowest-lying region, running along the southeastern border. The Red Lands, in the far south and southwest, are Luxembourg's industrial heartland and home to many of Luxembourg's largest towns.

The border between Luxembourg and Germany is formed by three rivers: the Moselle, the Sauer, and the Our. Other major rivers are the Alzette, the Attert, the Clerve, and the Wiltz. The valleys of the mid-Sauer and Attert form the border between the Gutland and the Oesling.

Environment

According to the 2012 Environmental Performance Index, Luxembourg is one of the world's best performers in environmental protection, ranking 4th out of 132 assessed countries.[65] In 2020 the country was ranked second out of 180 countries[66] Luxembourg also ranks 6th among the top ten most livable cities in the world by Mercer's.[67] The country wants to cut GHG emissions by 55% in 10 years and reach zero emissions by 2050. Luxemburg wants to increase fivefold its organic farming.[68] Luxembourg had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 1.12/10, ranking it 164th globally out of 172 countries.[69]

Luxembourg has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), marked by high precipitation, particularly in late summer. The summers are warm and winters cool.[70]

Economy

Luxembourg's stable and high-income market economy features moderate growth, low inflation, and a high level of innovation.[71] Unemployment is traditionally low, although it had risen to 6.1% by May 2012, due largely to the effect of the 2008 global financial crisis.[72] In 2011, according to the IMF, Luxembourg was the second richest country in the world, with a per capita GDP on a purchasing-power parity (PPP) basis of $80,119.[73] Its GDP per capita in purchasing power standards was 261% of the EU average (100%) in 2019.[74] Luxembourg is ranked 13th in The Heritage Foundation's Index of Economic Freedom,[75] 26th in the United Nations Human Development Index, and 4th in the Economist Intelligence Unit's quality of life index.[76]

The industrial sector, which was dominated by steel until the 1960s, has since diversified to include chemicals, rubber, and other products. During the past decades, growth in the financial sector has more than compensated for the decline in steel production. Services, especially banking and finance, account for the majority of the economic output. Luxembourg is the world's second largest investment fund centre (after the United States), the most important private banking centre in the Eurozone and Europe's leading centre for reinsurance companies. Moreover, the Luxembourg government has aimed to attract Internet start-ups, with Skype and Amazon being two of the many Internet companies that have shifted their regional headquarters to Luxembourg. Other high-tech companies have established themselves in Luxembourg, including 3D scanner developer/manufacturer Artec 3D.

In April 2009, concern about Luxembourg's banking secrecy laws, as well as its reputation as a tax haven, led to its being added to a "grey list" of nations with questionable banking arrangements by the G20. In response, the country soon after adopted OECD standards on exchange of information and was subsequently added into the category of "jurisdictions that have substantially implemented the internationally agreed tax standard".[77][78] In March 2010, the Sunday Telegraph reported that most of Kim Jong-Il's $4 billion in secret accounts is in Luxembourg banks.[79] Amazon.co.uk also benefits from Luxembourg tax loopholes by channeling substantial UK revenues as reported by The Guardian in April 2012.[80] Luxembourg ranked third on the Tax Justice Network's 2011 Financial Secrecy Index of the world's major tax havens, scoring only slightly behind the Cayman Islands.[81] In 2013, Luxembourg is ranked as the 2nd safest tax haven in the world, behind Switzerland.

In early November 2014, just days after becoming head of the European Commission, the Luxembourg's former Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker was hit by media disclosures—derived from a document leak known as Luxembourg Leaks—that Luxembourg under his premiership had turned into a major European centre of corporate tax avoidance.[82]

Agriculture employed about 2.1% percent of Luxembourg's active population in 2010, when there were 2200 agricultural holdings with an average area per holding of 60 hectares.[83]

Luxembourg has especially close trade and financial ties to Belgium and the Netherlands (see Benelux), and as a member of the EU it enjoys the advantages of the open European market.

With $171 billion in May 2015, the country ranks eleventh in the world in holdings of U.S. Treasury securities.[84] However, securities owned by non-Luxembourg residents, but held in custodial accounts in Luxembourg, are also included in this figure.[85]

As of 2019, public debt of Luxembourg was at $15,687,000,000, or a per capita debt of $25,554. The debt to GDP was 22.10%.[86]

Transport

Luxembourg has road, rail and air transport facilities and services. The road network has been significantly modernised in recent years with 147 km (91 mi) of motorways connecting the capital to adjacent countries. The advent of the high-speed TGV link to Paris has led to renovation of the city's railway station and a new passenger terminal at Luxembourg Airport was opened in 2008. Luxembourg city reintroduced trams in December 2017 and there are plans to open light-rail lines in adjacent areas within the next few years.

The number of cars per 1000 persons amount to 680.1 in Luxembourg — higher than all but two states, namely the Principality of Monaco and the British overseas territory of Gibraltar.[87]

On 29 February 2020 Luxembourg became the first country to introduce no-charge public transportation which will be almost completely funded through tax revenue.[88]

Communications

The telecommunications industry in Luxembourg is liberalised and the electronic communications networks are significantly developed. Competition between the different operators is guaranteed by the legislative framework Paquet Telecom[89] of the Government of 2011 which transposes the European Telecom Directives into Luxembourgish law. This encourages the investment in networks and services. The regulator ILR – Institut Luxembourgeois de Régulation[90] ensures the compliance to these legal rules.

Luxembourg has modern and widely deployed optical fiber and cable networks throughout the country. In 2010, the Luxembourg Government launched its National strategy for very high-speed networks with the aim to become a global leader in terms of very high-speed broadband by achieving full 1 Gbit/s coverage of the country by 2020.[91] In 2011, Luxembourg had an NGA coverage of 75%.[92] In April 2013 Luxembourg featured the 6th highest download speed worldwide and the 2nd highest in Europe: 32,46 Mbit/s.[93] The country's location in Central Europe, stable economy and low taxes favour the telecommunication industry.[94][95][96]

It ranks 2nd in the world in the development of the Information and Communication Technologies in the ITU ICT Development Index and 8th in the Global Broadband Quality Study 2009 by the University of Oxford and the University of Oviedo.[97][98][99][100]

Luxembourg is connected to all major European Internet Exchanges (AMS-IX Amsterdam,[101] DE-CIX Frankfurt,[102] LINX London),[103] datacenters and POPs through redundant optical networks.[104][105][106][107][108] In addition, the country is connected to the virtual meetme room services (vmmr)[109] of the international data hub operator Ancotel.[110] This enables Luxembourg to interconnect with all major telecommunication operators[111] and data carriers worldwide. The interconnection points are in Frankfurt, London, New York and Hong Kong.[112] Luxembourg has established itself as one of the leading financial technology (FinTech) hubs in Europe, with the Luxembourg government supporting initiatives like the Luxembourg House of Financial Technology.[113]

Some 20 data centres[114][115][116] are operating in Luxembourg. Six data centers are Tier IV Design certified: three of ebrc,[117] two of LuxConnect[118][119] and one of European Data Hub.[120] In a survey on nine international data centers carried out in December 2012 and January 2013 and measuring availability (up-time) and performance (delay by which the data from the requested website was received), the top three positions were held by Luxembourg data centers.[121][122]

Demographics

Largest towns

Ethnicity

|

The people of Luxembourg are called Luxembourgers.[124] The immigrant population increased in the 20th century due to the arrival of immigrants from Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, and Portugal, with the majority coming from the latter: in 2013 there were about 88,000 inhabitants with Portuguese nationality.[125] In 2013, there were 537,039 permanent residents, 44.5% of which were of foreign background or foreign nationals; the largest foreign ethnic groups were the Portuguese, comprising 16.4% of the total population, followed by the French (6.6%), Italians (3.4%), Belgians (3.3%) and Germans (2.3%). Another 6.4% were of other EU background, while the remaining 6.1% were of other non-EU, but largely other European, background.[126]

Since the beginning of the Yugoslav wars, Luxembourg has seen many immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Serbia. Annually, over 10,000 new immigrants arrive in Luxembourg, mostly from the EU states, as well as Eastern Europe. In 2000 there were 162,000 immigrants in Luxembourg, accounting for 37% of the total population. There were an estimated 5,000 illegal immigrants in Luxembourg in 1999.[127]

Language

The three official languages of Luxembourg are French, German and Luxembourgish: a Franconian language specific to the local population which is partially mutually intelligible with the neighboring High German, but which also includes more than 5,000 words of French origin.[128][129] Every citizen or resident has the right to address the administration in the language of their choice among the three official languages and to be answered in that language.

Luxembourg is largely multilingual; while a 2009 survey revealed that French was the language spoken by most inhabitants (99%), Luxembourgish (82%), German (81%) and English (72%) were also spoken by large sections of the population.[130]

Each of the three official languages is used as the primary language in certain spheres of everyday life, without being exclusive. Luxembourgish is the national language of the Grand Duchy and is considered the mother tongue or "language of the heart" for the local population,[131] being the language that Luxembourgers generally use to speak to each other. However, despite a recent increase in the production of novels in the language, it is seldom used as written language, and the numerous expatriate workers (approximately 60% of the population) also generally do not use it to speak to each other.

Most official business and written communication is carried out in French, which is also the language mostly used for public communication, with written official statements, advertising displays and road signs generally being in French. Due to the historical influence of the Napoleonic Code on the legal system of the Grand Duchy, French is also the sole language of the legislation and generally the preferred language of the government, administration and justice. The parliamentary debates are however mostly conducted in Luxembourgish, whereas the written government communications and the official documents (e.g. administrative or judicial decisions, passports etc.) are drafted only in French.

Although professional life is largely multilingual, French is described by private sector business leaders as the main working language of their companies (56%), followed by Luxembourgish (20%), English (18%), and German (6%).[132]

German is very often used in much of the media along with French.[133]

Due to the large community of Portuguese origin, the Portuguese language is de facto fairly present in Luxembourg though it remains limited to the relationships inside this community; although Portuguese does not have any official status, the administration sometimes holds certain informative documents available in Portuguese.

Religion

Luxembourg is a secular state, but the state recognises certain religions as officially mandated religions. This gives the state a hand in religious administration and appointment of clergy, in exchange for which the state pays certain running costs and wages. Religions covered by such arrangements are Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Greek Orthodoxy, Anglicanism, Russian Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, Calvinism, Mennonitism, and Islam.[134]

Since 1980 it has been illegal for the government to collect statistics on religious beliefs or practices.[135] An estimation by the CIA Factbook for the year 2000 is that 87% of Luxembourgers are Catholic, including the grand ducal family, the remaining 13% being made up of Protestants, Orthodox Christians, Jews, Muslims, and those of other or no religion.[136] According to a 2010 Pew Research Center study, 70.4% are Christian, 2.3% Muslim, 26.8% unaffiliated, and 0.5% other religions.[137]

According to a 2005 Eurobarometer poll,[138] 44% of Luxembourg citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", whereas 28% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", and 22% that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, god, or life force".

Education

Luxembourg's education system is trilingual: the first years of primary school are in Luxembourgish, before changing to German; while in secondary school, the language of instruction changes to French.[139] Proficiency in all three languages is required for graduation from secondary school, but half the students leave school without a certified qualification, with the children of immigrants being particularly disadvantaged.[140] In addition to the three national languages, English is taught in compulsory schooling and much of the population of Luxembourg can speak English. The past two decades have highlighted the growing importance of English in several sectors, in particular the financial sector. Portuguese, the language of the largest immigrant community, is also spoken by large segments of the population, but by relatively few from outside the Portuguese-speaking community.[141]

The University of Luxembourg is the only university based in Luxembourg. In 2014, Luxembourg School of Business, a graduate business school, has been created through private initiative and has received the accreditation from the Ministry of Higher Education and Research of Luxembourg in 2017.[142][143] Two American universities maintain satellite campuses in the country, Miami University (Dolibois European Center) and Sacred Heart University (Luxembourg Campus).[144]

Health

According to data from the World Health Organization, healthcare spending on behalf of the government of Luxembourg topped $4.1 Billion, amounting to about $8,182 for each citizen in the nation.[145][146] The nation of Luxembourg collectively spent nearly 7% of its Gross Domestic Product on health, placing it among the highest spending countries on health services and related programs in 2010 among other well-off nations in Europe with high average income among its population.[147]

Culture

Luxembourg has been overshadowed by the culture of its neighbours. It retains a number of folk traditions, having been for much of its history a profoundly rural country. There are several notable museums, located mostly in the capital. These include the National Museum of History and Art (NMHA), the Luxembourg City History Museum, and the new Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art (Mudam). The National Museum of Military History (MNHM) in Diekirch is especially known for its representations of the Battle of the Bulge. The city of Luxembourg itself is on the UNESCO World Heritage List, on account of the historical importance of its fortifications.[148]

The country has produced some internationally known artists, including the painters Théo Kerg, Joseph Kutter and Michel Majerus, and photographer Edward Steichen, whose The Family of Man exhibition has been placed on UNESCO's Memory of the World register, and is now permanently housed in Clervaux. Movie star Loretta Young was of Luxembourgish descent.

Luxembourg was a founding participant of the Eurovision Song Contest, and participated every year between 1956 and 1993, with the exception of 1959. It won the competition a total of five times, 1961, 1965, 1972, 1973 and 1983 and hosted the contest in 1962, 1966, 1973, and 1984, but only eight of its 38 entries were performed by Luxembourgish artists.

Luxembourg was the first city to be named European Capital of Culture twice. The first time was in 1995. In 2007, the European Capital of Culture[149] was to be a cross-border area consisting of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Rheinland-Pfalz and Saarland in Germany, the Walloon Region and the German-speaking part of Belgium, and the Lorraine area in France. The event was an attempt to promote mobility and the exchange of ideas, crossing borders physically, psychologically, artistically and emotionally.

Luxembourg was represented at the World Expo 2010 in Shanghai, China, from 1 May to 31 October 2010 with its own pavilion.[150][151] The pavilion was based on the transliteration of the word Luxembourg into Chinese, "Lu Sen Bao", which means "Forest and Fortress". It represented Luxembourg as the "Green Heart in Europe".[152]

Sports

.jpg.webp)

Unlike most countries in Europe, sport in Luxembourg is not concentrated upon a particular national sport, but encompasses a number of sports, both team and individual. Despite the lack of a central sporting focus, over 100,000 people in Luxembourg, out of a total population of near 500,000–600,000, are licensed members of one sports federation or another.[153] The largest sports venue in the country is d'Coque, an indoor arena and Olympic swimming pool in Kirchberg, north-eastern Luxembourg City, which has a capacity of 8,300. The arena is used for basketball, handball, gymnastics, and volleyball, including the final of the 2007 Women's European Volleyball Championship. The national stadium (also the country's largest) is the Stade Josy Barthel, in western Luxembourg City; named after the country's only official Olympic gold medallist, the stadium has a capacity of 8,054.

Cuisine

Luxembourg cuisine reflects its position on the border between the Latin and Germanic worlds, being heavily influenced by the cuisines of neighboring France and Germany. More recently, it has been enriched by its many Italian and Portuguese immigrants.

Most native Luxembourg dishes, consumed as the traditional daily fare, share roots in the country's folk dishes the same as in neighboring Germany.

Luxembourg sells the most alcohol in Europe per capita.[154] However, the large proportion of alcohol purchased by customers from neighboring countries contributes to the statistically high level of alcohol sales per capita; this level of alcohol sales is thus not representative of the actual alcohol consumption of the Luxembourg population.[155]

Media

The main languages of media in Luxembourg are French and German. The newspaper with the largest circulation is the German-language daily Luxemburger Wort.[156] Because of the strong multilingualism in Luxembourg, newspapers often alternate articles in French and articles in German, without translation. In addition there are both English and Portuguese radio and national print publications, but accurate audience figures are difficult to gauge since the national media survey by ILRES[157] is conducted in French.

Luxembourg is known in Europe for its radio and television stations (Radio Luxembourg and RTL Group). It is also the uplink home of SES, carrier of major European satellite services for Germany and Britain.

Due to a 1988 law that established a special tax scheme for audiovisual investment, the film and co-production in Luxembourg has grown steadily.[158] There are some 30 registered production companies in Luxembourg.[159][160]

Luxembourg won an Oscar in 2014 in the Animated Short Films category with Mr Hublot.

Notable Luxembourgers

Footnotes

- Strictly speaking, there is no official language in Luxembourg. No language is mentioned in the Constitution; other laws only speak about Luxembourgish as the "national language" and French and German as "administrative languages".

- European Union since 1993.

- Luxembourgish: Groussherzogtum Lëtzebuerg [ˈɡʀəʊ̯s.hɛχtsoːχtum ˈlətsəbuːə̯ɕ]; French: Grand-Duché de Luxembourg [ɡʁɑ̃ dyʃe də lyksɑ̃buʁ]; German: Großherzogtum Luxemburg [ˈɡʁoːs.hɛɐ̯tsoːktuːm ˈlʊksm̩bʊɐ̯k]

Further reading

- Kreins, Jean-Marie (2003). Histoire du Luxembourg (in French) (3rd ed.). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-053852-3.

- Thewes, Guy (July 2003). Les gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF) (in French) (Édition limitée ed.). Luxembourg City: Service Information et Presse. ISBN 2-87999-118-8. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Plan d'action national luxembourgeois en matière de TIC et de haut-débit

- CEE- Europe's Digital Competitiveness Report –Volume 2: i2010 –ICT Country Profiles- page 40-41

- Inauguration of LU-CIX

- Art and Culture in Luxembourg

References

- "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Eurobarometer 90.4: Attitudes of Europeans towards Biodiversity, Awareness and Perceptions of EU customs, and Perceptions of Antisemitism. European Commission. Retrieved 15 July 2019 – via GESIS.

- "Surface water and surface water change". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Statistiques // Luxembourg". statistiques.public.lu. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- "Luxembourg". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "Europe :: Luxembourg — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Decision of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States on the location of the seats of the institutions (12 December 1992)". Centre virtuel de la connaissance sur l'Europe. 2014. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "What languages do people speak in Luxembourg?". luxembourg.public.lu. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "Population et emploi". Le Portail des Statistiques. Statec and State of Luxembourg. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Country comparison :: POPULATION growth rate". The World Factbook. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Krouse, Sarah (1 January 2018). "Piping Hot Gromperekichelcher, Only if You Pass the Sproochentest". The Wall Street Journal. p. 1.

- "City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications". World Heritage List. UNESCO, World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. p. 1. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- Kreins, Jean-Marie (2010). Histoire du Luxembourg (5 ed.). Paris, France: Presses Universitaires de France.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. p. 2. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- "Henry VII | Holy Roman emperor". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Luxembourg - History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- "Luxembourg - History". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- A propos... Histoire du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Luxembourg: Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, Département édition. 2008. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-2-87999-093-4.

- "European Union | Definition, Purpose, History, & Members". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Timeline: Luxembourg – A chronology of key events BBC News Online, 9 September 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- "Luxembourg - Independent Luxembourg". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Luxembourg | national capital, Luxembourg". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Asselborn's final Security Council meeting". Luxemburger Wort. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Global Ranking – Visa Restriction Index 2020" (PDF). Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "Emperor Charles IV elected Greatest Czech of all time". Radio Prague. 13 June 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- Kreins (2003), p. 20

- "History of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2012.

- Kreins (2003), p. 39

- Johan Christiaan Boogman: Nederland en de Duitse Bond 1815–1851. Diss. Utrecht, J. B. Wolters, Groningen / Djakarta 1955, pp. 5–8.

- Thewes, Guy (2006) (PDF). Les gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (2006), p. 208

- "LUXEMBURG Geschiedenis". Landenweb.net. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia 1997

- Kreins (2003), p. 76

- Harmsen, Robert; Högenauer, Anna-Lena (28 February 2020), "Luxembourg and the European Union", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1041, ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7

- Jean-Marie Kreins, Histoire du Luxembourg, 5th edition, Presses Universitaires de France, 2010

- Kreins (2003), pp. 80–81

- Kreins (2003), p. 84

- The Great European treaties of the nineteenth century. Oakes and Mowat. The Clarendon Press. 1918. p. 259.

- Maartje Abbenhuis, An Age of Neutrals: Great Power Politics, 1815–1914. Cambridge University Press (2014) ISBN 978-1107037601

- "The invasion of Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg". Judgment of the International Military Tribunal For The Trial of German Major War Criminals. London HMSO 1951.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Le Luxembourg décroche la lune", 'Official Portal of the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg', Government of Luxembourg. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- solutions, EIU digital. "Democracy Index 2016 - The Economist Intelligence Unit". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "The Luxembourgish government since 1848 (in French)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011.

- (in French and German) "Mémorial A, 1868, No. 25" (PDF). Service central de législation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- "Constitution of Luxembourg" (PDF). Service central de législation. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- "Structure of the Conseil d'Etat". Conseil d'Etat. Archived from the original on 19 June 2006. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- "Carte des communes – Luxembourg.lu – Cartes du Luxembourg". Luxembourg.public.lu. 21 September 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "Luxembourg - Communications". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "The European institutions in Luxembourg". luxembourg.public.lu. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- SA, Interact. "Accueil". www.armee.lu (in French). Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- "Luxembourg". Aeroflight.co.uk. 8 September 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- "A400M Loadmaster, Future Large Aircraft – FLA, Avion de Transport Futur – ATF", GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- "Luxembourg Army History". 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "Where is Luxembourg?". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- "Mountains in Luxembourg" (PDF). Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2010.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), recueil de statistiques par commune. statistiques.public.lu (2003) p. 20

- "2012 EPI :: Rankings – Environmental Performance Index". yale.edu. 5 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- "WHAT IS THE GREENEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD?". ATLAS & BOOTS. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- "MAE – Luxembourg City in the top 10 of the most "livable" cities / News / New York CG / Mini-Sites". Newyork-cg.mae.lu. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- SCHNUER, CORDULA. "LUX MUST "REDOUBLE ITS EFFORTS" TO MEET CLIMATE TARGETS: OECD". Delano. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507. S2CID 228082162.

- "Luxembourg". Stadtklima (Urban Climate). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- "The Global Innovation Index 2012" (PDF). INSEAD. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Statistics Portal // Luxembourg – Home". Statistiques.public.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Data refer mostly to the year 2011. World Economic Outlook Database-April 2012, International Monetary Fund. Accessed on 18 April 2012.

- "GDP per capita in PPS". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "2011 Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- "World Life Quality Index 2005" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- "Luxembourg makes progress in OECD standards on tax information exchange". OECD. 8 July 2009.

- "A progress report on the jurisdictions surveyed by the OECD Global Forum" (PDF). OECD. July 2009.

- "Kim Jong-il $4bn emergency fund in European banks". Telegraph. March 2010.

- Griffiths, Ian (4 April 2012). "How one word change lets Amazon pays less tax on its UK activities". London: TheGuardian.

- "Embargo 4 October 0.01 AM Central European Times" (PDF). Financialsecrecyindex.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Luxembourg tax files: how tiny state rubber-stamped tax avoidance on an industrial scale". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Agricultural census in Luxembourg". Eurostat. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- "Major foreign holders of treasury securities". U.S. Department of the Treasury.

- "What are the problems of geographic attribution for securities holdings and transactions in the TIC system?". U.S. Treasury International Capital (TIC) reporting system.

- "Luxembourg National Debt 2019". countryeconomy.com. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- "Top Ten: Die Länder mit der höchsten Pkw-Dichte – manager magazin – Unternehmen". Manager-magazin.de. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Calder, Simon (29 February 2020). "Luxembourg makes history as first country with free public transport". The Independent.

- "Legilux – Réseaux et services de communications électroniques". Legilux.public.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Institut Luxembourgeois de Régulation – Communications électroniques". Ilr.public.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Service des médias et des communications (SMC) – gouvernement.lu // L'actualité du gouvernement du Luxembourg". Mediacom.public.lu. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Study on broadband coverage 2011. Retrieved on 25 January 2013". Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "Household Download Index. Retrieved on 9 April 2013". Netindex.com. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "Eurohub Luxembourg – putting Europe at your fingertips" (PDF). Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2010.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade of Luxembourg. August 2008

- "Why Luxembourg? – AMCHAM". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "Financial express special issue on Luxembourg" (PDF). 23 June 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- pressinfo (23 February 2010). "Press Release: New ITU report shows global uptake of ICTs increasing, prices falling". Itu.int. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Luxembourg ranks on the top in the ITU ICT survey".

- "Global Broadband Quality Study". Socsci.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Global Broadband Quality Study Shows Progress, Highlights Broadband Quality Gap" (PDF). Said Business School, University of Oxford. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "ams-ix.net". ams-ix.net. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "de-cix.net". de-cix.net. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "linx.net". linx.net. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "ICT Business Environment in Luxembourg". Luxembourgforict.lu. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- Tom Kettels (15 May 2009). "ICT And E-Business – Be Global from Luxembourg" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "PricewaterhouseCoopers Invest in Luxembourg". Pwc.com. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Why Luxembourg? A highly strategic position in the heart of Europe". teralink.lu. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "ITU-T ICT Statistics : Luxembourg". Itu.int. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Telx Partners with German Hub Provider ancotel to Provide Virtual Connections between U.S. and Europe" (PDF). Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Globale Rechenzentren | Colocation mit niedrigen Latenzen für Finanzunternehmen, CDNs, Enterprises & Cloud-Netzwerke bei Equinix" (in German). Ancotel.de. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Ancotel – Telecommunication Operator References". Ancotel.de. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Networks Accessible in Frankfurt via the VMMR Solution offered by Telx/ancotel" (PDF). Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- "Luxembourg's politicians pin economic hopes on fintech drive". Financial Times. 23 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "European Datacentres: Luxembourg". Ict.luxembourg.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Luxembourg as a Centre for Online and ICT Business (pdf)" (PDF). SMediacom.public.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Invest, Innovate, Export | Luxembourg as a smart location for business". Trade and Invest. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "ebrc Datacenter Facilities". Ebrc.lu. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "LuxConnect ICT campus Bettembourg DC 1.1". Luxconnect.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "LuxConnect ICT campus Bissen/Roost DC 2". Luxconnect.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Uptime Tier Certification". Uptimeinstitute.com. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "New data center study: Luxembourg in pole position". Ict.luxembourg.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Soluxions magazine: Luxembourg en pole position". Soluxions-magazine.com. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "International migrant stock: The 2017 revision". United Nations.

- "Luxembourg Presidency – Being a Luxembourger". Eu2005.lu. 29 December 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Population par sexe et par nationalité (x 1 000) 1981, 1991, 2001–2013". Le portail des Statistiques. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "La progression de la population du Grand-Duché continue: 537 039 résidants au 1er janvier 2013." Statnews 16/2013, op statec.lu, 18 April 2013. (in French).

- Amanda Levinson. "The Regularisation of Unauthorised Migrants: Literature Survey and Country Case Studies – Regularisation programmes in Luxembourg" (PDF). Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, University of Oxford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2005. Retrieved 2 September 2006.

- "Origins of Luxembourgish (in French)". Migration Information Source.

- "Parlement européen – Lëtzebuergesch léieren (FR)". Europarl.europa.eu. 14 December 2000. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Fernand Fehlen, BaleineBis : une enquête sur un marché linguistique multilingue en profonde mutation. LuxemburgsSprachenmarkt in Wandel, Luxembourg, SESOPI, 2009

- "Europeans and Their Languages" (PDF). European Commission. 2006. p. 7. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Les langues dans les offres d'emploi au Luxembourg (1984-2014), Université du Luxembourg, IPSE Identités, Politiques, Sociétés, Espaces, Working Paper, Juin 2015

- "À propos des langues" (PDF) (in French). Service Information et Presse. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- "D'Wort article (German)" (in French). www.wort.lu. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- "Mémorial A, 1979, No. 29" (PDF) (in French). Service central de législation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 1 August 2006.

- "World Factbook – Luxembourg". Central Intelligence Agency. 19 December 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- "Table: Religious Composition by Country, in Percentages | Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project". Features.pewforum.org. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Eurobarometer on Social Values, Science and technology 2005 Archived 24 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine – page 11

- "The Trilingual Education system in Luxembourg". Tel2l – Teacher Education by Learning through two languages, University of Navarra. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Immigration in Luxembourg: New Challenges for an Old Country". Migration Information Source. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Parlement européen – Lëtzebuergesch léieren (FR)". Europarl.europa.eu. 14 December 2000. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- "Arrêté ministériel du 29 août 2017 portant accréditation de " Luxembourg School of Business " (LSB) en tant qu'établissement d'enseignement supérieur spécialisé et du programme d'études à temps partiel " Master of Business Administration " (MBA) offert par l'établissement précité. - Legilux". legilux.public.lu. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Les universités". www.luxembourg.public.lu (in French). Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Home | John E. Dolibois European Center | Miami University". www.units.miamioh.edu. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe". www.euro.who.int. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Health Expenditure and Financing". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- "Overview of the Healthcare System in Luxembourg". Health Management EuroStat. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Culture". Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, Luxembourg. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- "Luxembourg and Greater Region, European Capital of Culture 2007" (PDF). June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2011.

- "Environmental Report for Expo 2010 Shanghai China" (PDF). June 2009. p. 85. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011.

- "Luxembourg pavilion at the World Expo 2010 Shanghai" (PDF).

- "Luxembourg pavilion displays green heart of Europe" (PDF). Shanghai Daily. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- "Luxembourg". Council of Europe. 2003. Archived from the original on 23 June 2004. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- "World/Global Alcohol/Drink Consumption 2009". Finfacts.ie. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Consommation annuelle moyenne d'alcool par habitant, Catholic Ministry of Health" (PDF). sante.gouv.fr. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2012.

- "Luxemburger Wort". Wort.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "TNS ILRES – Home". Tns-ilres.com. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Luxembourg, a film country". Eu2005.lu. 29 December 2004. Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- "Film Fund Luxembourg". En.filmfund.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Luxembourgish Film Production Companies". Cna.public.lu. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

External links

- The Official Portal of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

- Luxembourg from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Luxembourg at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Luxembourg. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Luxembourg at Curlie

- Luxembourg profile from the BBC News

- Luxembourg's Constitution of 1868 with Amendments through 2009, English Translation 2012

Wikimedia Atlas of Luxembourg

Wikimedia Atlas of Luxembourg

.svg.png.webp)