Madame Berthe's mouse lemur

Madame Berthe's mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae) or Berthe's mouse lemur is the smallest of the mouse lemurs and the smallest primate in the world; the average body length is 9.2 cm (3.6 in) and seasonal weight is around 30 g (1.1 oz).[4] Microcebus berthae is one of many species of Malagasy lemurs that came about through extensive speciation, caused by unknown environmental mechanisms and conditions.[5]

| Madame Berthe's mouse lemur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Strepsirrhini |

| Family: | Cheirogaleidae |

| Genus: | Microcebus |

| Species: | M. berthae |

| Binomial name | |

| Microcebus berthae Rasoloarison et al., 2000[3] | |

| |

| Distribution of M. berthae[1] | |

This primate is found chiefly in the Kirindy Forest in western Madagascar.[6] After its discovery in 1992 in the dry deciduous forest of western Madagascar, it was initially thought to represent a rediscovery of M. myoxinus, but comparative morphometric and genetic studies revealed its status as a new species, M. berthae.[7]

This lemur is named after the conservationist and primatologist Berthe Rakotosamimanana of Madagascar, who was the Secretary General of the Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche des Primates (GERP) from its founding until her death in 2005.[8]

Physical description

Microcebus berthae has short, dense dorsal pelage that is bicolored cinnamon and yellow ochre. The middorsal stripe is tawny in color. The midventral area of this species is chamois in color while the flanks are a mixture of pale chamois and light pale neutral gray. The dorsal and ventral underfur is neutral blackish neutral gray in color. The tail has short hair that is tawny. The crown and ears are also tawny in color. The orbits are surrounded by a narrow dark band. The area between the eyes is cinnamon in color. The hands and feet are dull beige.

Distribution and habitat

Madame Berthe's mouse lemur is known to live in Kirindy Forest in Madagascar. It is now likely extirpated from the Andranomena Special Reserve and the Analabe private reserve.[9] Madame Berthe's mouse lemurs use the tangles of tree vines to sleep in. Because of its limited spread, it is thought that they are specialist creatures that will only live in that one specific environment. Another idea suggests that they most likely compete with the gray mouse lemur (M. murinus), chiefly for resources.

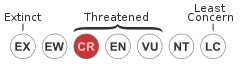

Because of the high rate of deforestation in the surrounding Menabe forests (52%) between 1985 and 2000, less than 22,000 hectares (54,000 acres) of inhabitable forests remained between Kirindy Park, the Tsiribihina River, and the Reserve. Given that this lemur occurs at 0.36 lemurs per ha, it is estimated that about 7,920 mouse lemurs were left in the area in the year 2000. With deforestation continuing to occur on the island nation, the species is listed as critically endangered, at best.

Behavior

Microcebus berthae are typically solitary foragers, but are not without social interaction with other members of their species. About half the time, they sleep alone. Otherwise, they can be found sleeping next to one or more lemurs, with no preference or prejudice to close relatives or members of the opposite sex. Be it alone or in a group, Microcebus berthae tend to sleep in leaf nests in trees, or without a nest, in hole-like structures. On occasion, the paths of two members of the species may cross, leading to different kinds of social encounters. Some encounters involve bouts of mutual grooming, sex, or huddling (an activity which can last up to 23 minutes). Other meet-ups between lemurs might include chasing, biting and grabbing. Overall, male-male and female-female interactions do not differ qualitatively. Unlike other species of lemur, Microcebus berthae do not hibernate during the cold-dry season, instead compensating for food scarcity with a larger than average home range.[10]

In a population of Microcebus berthae, males significantly outnumber females. Despite there being no sexual dimorphism in skull length, canine height, or tail length, the average female is larger than the average male in head-body length and head width. Average body mass, while relatively equal during mating season, becomes smaller for males in the duration of time excluding mating season. Males have a home range of about 4.92 hectares (12.2 acres), while females have a home range of about 2.50 hectares (6.2 acres). Females tend to remain in a home range that is close to, or includes their place of birth. This is the opposite of males, who tend to disperse from their place of birth. The home ranges of individual lemurs tend to overlap with each other, with female home ranges overlapping with that of one or two other females, and male home ranges overlapping with that of up to nine other males.[10]

Social systems of M. berthae are more similar to the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) than the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius), i.e. Madame Berthe's mouse lemur is sexually promiscuous rather than monogamous. The range in distance of males is larger than that of the females in both Microcebus species, both before and after mating seasons. Research has also been conducted on the distribution of sleeping sites, as well as on testes size and the presence of vaginal plugs. Study of capture rates and physiological proof reveals no evidence that M. berthae has a hibernation season, which increases the chances of sexual activity within the species.[11]

Ecology

Mouse lemurs are considered to be a cryptic species complex. The species-rich mouse lemur genus Microcebus is distributed over nearly all remaining forest areas of Madagascar with a high variability in species distribution patterns and are very similar morphologically. They are so similar, that the gray mouse lemur was considered the only mouse lemur until recent studies proved it to be otherwise. Along with other morphological similarities, the Madame Berthe's mouse lemur and the gray mouse lemur share a similar diet (both containing the same food groups but in different proportions) and live in the same region of western Madagascar. Both of these Microcebus species have an omnivorous diet, and used the same food sources, including sugary homopteran secretions, fruit, flowers, gum, arthropods and small vertebrates (e.g. geckos, chameleons). Because of their recent common ancestry, closely related species ought to exhibit high similarities in their use of biotic and abiotic resources, susceptibility to predators and responses to disturbances and stress. However, despite the overlapping niches, studies have shown that the territories of the two mouse lemur species have very little to no overlap. The Madame Berthe's mouse lemur population is sparse and spread out over a more widespread area; while the gray mouse lemurs had a much denser population in a smaller area.[7]

The reason for the mouse lemur species' mutual avoidance is not yet clearly known. The gray mouse lemur has several competitive advantages over Madame Berthe's mouse lemur. It is about twice as large as Madame Berthe's mouse lemur. It also has the advantages of being a generalist, and having fewer deaths by predation, with 70% predation mortality for Madame Berthe's mouse lemur, vs. 50% predation mortality for the gray mouse lemur. The areas used exclusively by each species share structural characteristics and food sources. Gray mouse lemurs are able to live in more types of vegetation than Madame Berthe's mouse lemur yet have smaller, denser territories. This suggests that their avoidance does not stem from environmental differences, but rather by competitive coexistence.[7]

Diet

Madame Berthe's mouse lemur shares its niche with the sympatric gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus). Both lemurs feeding ecology suggests that there is a coexistence behavior between the two lemur species. Both species are found in western Madagascar's highly seasonal dry deciduous forest. Madame Berthe's mouse lemur has a very narrow feeding niche unlike the sympatric gray mouse lemur which has a much broader niche. The feeding ecology and the types of food available depend on the type of season in the niche of Microcebus berthae and Microcebus murinus. During the wet, rainy season, more unripe fruit is available which decreases its abundance in the dry season. However, ripe fruit are available all year round with maximum abundance in the dry season. As a food source, flying insects are available in both seasons, but are abundant in the wet season.[12]

Madame Berthe's mouse lemur is an omnivore and mainly feeds on fruits and flowers of different tree and shrub species, insect secretions, gum, arthropods and small vertebrates like geckos and chameleons. Compared to the dry and the wet season of Madame Berthe's mouse lemur's niche, it spends more time feeding in the dry season while the wet season is used for mating. Compared to the sympatric gray mouse lemur, Madame Berthe's mouse lemur eats mainly insects, and fruit only occasionally. Similar to the sympatric gray mouse lemur, Madame Berthe's mouse lemur is able to adapt to the fluctuation of resources. There is a high overlap in the feeding niche of both lemurs suggesting that they avoid competition by mutually excluding each other on a small scale.[12]

Status

As of December 2019, Madame Berthe's mouse lemur is rated critically endangered by the IUCN Red List. The main threat to this species is deforestation and habitat degradation from Slash-and-burn agriculture, illegal logging and charcoal production. The Menabe-Antimena Protected Area has been established to protect the Kirindy Forest and the surrounding areas. However, this has been poorly enforced and deforestation proceeds unhindered. If the deforestation continues at the current rate, it is estimated that Madame Berthe's mouse lemur will become extinct within 10 years. As of 2019, there are no Madame Berthe's mouse lemurs being kept in captivity.[9]

References

- Markolf, M., Schäffler, L. & Kappeler, P. (2020). "Microcebus berthae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T41573A115579496. Retrieved 12 July 2020.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Gron KJ. (11 February 2009). Primate Factsheets: Mouse lemur (Microcebus) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology . Accessed 2009 August

- Rakotondranary, S. J.; Hapke, A.; Ganzhorn, J. R. U. (2011). "Distribution and Morphological Variation of Microcebus spp. Along an Environmental Gradient in Southeastern Madagascar". International Journal of Primatology. 32 (5): 1037. doi:10.1007/s10764-011-9521-z.

- Mittermeier, R.A.; et al. (2006). Lemurs of Madagascar (2nd ed.). Conservation International. pp. 104–107. ISBN 978-1-881173-88-5.

- Dammhahn, M; Kappeler, P. M. (2008). "Small-scale coexistence of two mouse lemur species (Microcebus berthae and M. Murinus) within a homogeneous competitive environment". Oecologia. 157 (3): 473–83. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1079-x. PMC 2515545. PMID 18574599.

- Gould, Lisa; Michelle Sauther (2006). Lemurs: Ecology and Adaptation (1st ed.). University of Chicago. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-387-34586-4.

- Markolf, M., Schäffler, L. & Kappeler, P. 2020. Microcebus berthae. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T41573A115579496. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T41573A115579496.en. Downloaded on 18 November 2020.

- Dammhahn, M.; Kappeler, P. M. (2005). "Social System of Microcebus berthae, the World's Smallest Primate". International Journal of Primatology. 26 (2): 407. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-2931-z.

- Schwab, D.; Ganzhorn, J. R. U. (2004). "Distribution, Population Structure and Habitat Use of Microcebus berthae Compared to Those of Other Sympatric Cheirogalids". International Journal of Primatology. 25 (2): 307. doi:10.1023/B:IJOP.0000019154.17401.90.

- Dammhahn, M.; Kappeler, P. M. (2008). "Comparative Feeding Ecology of Sympatric Microcebus berthae and M. Murinus". International Journal of Primatology. 29 (6): 1567. doi:10.1007/s10764-008-9312-3.

External links

- Madame Berthe's mouse lemur media from ARKive