Magicicada septendecim

Magicicada septendecim, sometimes called the Pharaoh cicada or the 17-year locust, is native to Canada and the United States and is the largest and most northern species of periodical cicada with a 17-year lifecycle.[2]

| Magicicada septendecim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. septendecim |

| Binomial name | |

| Magicicada septendecim | |

Description

Like other species included in Magicicada, the insect's eyes and wing veins are reddish and its dorsal thorax is black. It is distinguished by broad orange stripes on its abdomen and a unique, high-pitched song said to resemble someone calling "weeeee-whoa" or "Pharaoh",[3] features it shares with the newly discovered 13-year species Magicicada neotredecim.[4]

Because of similarities between M. septendecim and the two closely related 13-year species M. neotredecim and M. tredecim, the three species are often described together as "decim periodical cicadas."

Life Cycle

Their median life cycle from egg to natural adult death is around seventeen years. However, their life cycle can range between thirteen and twenty-one years.[5]

Historical Accounts of Periodicity

Historical accounts cite reports of 15- to 17-year recurrences of enormous numbers of noisy emergent cicadas ("locusts") written as early as 1733.[6][7] Pehr Kalm, a Swedish naturalist visiting Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1749 on behalf of his nation's government, observed in late May one such emergence.[6][8] When reporting the event in a paper that a Swedish academic journal published in 1756, Kalm wrote:

The general opinion is that these insects appear in these fantastic numbers in every seventeenth year. Meanwhile, except for an occasional one which may appear in the summer, they remain underground.

There is considerable evidence that these insects appear every seventeenth year in Pennsylvania.[8]

Kalm then described documents (including one that he had obtained from Benjamin Franklin) that had recorded in Pennsylvania the emergence from the ground of large numbers of cicadas during May 1715 and May 1732. He noted that the people who had prepared these documents had made no such reports in other years.[8] Kalm further noted that others had informed him that they had seen cicadas only occasionally before the insects appeared in large swarms during 1749.[8] He additionally stated that he had not heard any cicadas in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in 1750 in the same months and areas in which he had heard many in 1749.[8] The 1715 and 1732 reports, when coupled with his own 1749 and 1750 observations, supported the previous "general opinion" that he had cited.

Kalm summarized his findings in a paper translated into English in 1771,[9] stating:

There are a kind of Locusts which about every seventeen years come hither in incredible numbers .... In the interval between the years when they are so numerous, they are only seen or heard single in the woods.[6][10]

Based on Kalm's account and a specimen that Kalm had provided, Carl Linnaeus gave to the insect the Latin name of Cicada septendecim in the 10th edition of his Systema Naturae, which was published in Stockholm in 1758.[2][11]

In 1766, Moses Bartram described in his Observations on the cicada, or locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 years the next appearance of the brood that Kalm had observed in 1749. Bartram noted that upon hatching from eggs deposited in the twigs of trees, the young insects ran down to the earth and "entered the first opening that they could find". He reported that he had been able to discover them 10 feet (3 m) below the surface, but that others had reportedly found them 30 feet (9 m) deep.[12]

In 1775, Thomas Jefferson recorded in his "Garden Book" the insect's 17-year periodicity, writing that an acquaintance remembered "great locust years" in 1724 and 1741, that he and others recalled another such year in 1754 and that the insects had again emerged from the ground at Monticello in 1775. He noted that the females lay their eggs in the small twigs of trees while above ground.[13]

In April 1800, Benjamin Banneker, who lived near Ellicott's Mills, Maryland, wrote in his record book that he recalled a "great locust year" in 1749, a second in 1766 during which the insects appeared to be "full as numerous as the first", and a third in 1783. He predicted that the insects "may be expected again in the year 1800, which is seventeen years since their third appearance to me".[14]

References

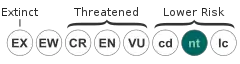

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Magicicada septendecim". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T12691A3373584. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T12691A3373584.en.

- Alexander, Richard D.; Moore, Thomas E. (1962). "The Evolutionary Relationships of 17-Year and 13-Year Cicadas, and Three New Species (Homoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada)" (PDF). University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- Stranahan, Nancy. "Nature Notes from the Eastern Forest". Arc of Appalachia. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- "Periodical Cicada Page". University of Michigan. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- Campbell, Matthew (18 August 2015). "Genome expansion via lineage splitting and genome reduction in the cicada endosymbiont Hodgkinia - Supporting Information" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (33): 3. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421386112. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Marlatt, C.L (1898). The Periodical Cicada in Literature. The Periodical Cicada: An Account of Cicada Septendecim, Its Natural Enemies and the Means of Preventing its Injury, Together With A Summary of the Distribution of the Different Broods (Bulletin No. 14 - New Series, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Division of Entomology). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 112–118. OCLC 10684275. Retrieved 2017-05-21 – via Google Books.

- Dudley, Paul (1733). Periodical Revolutions. Additional Manuscripts 4433, Folios 4-11, Division of Manuscripts of the British Library, London. ISBN 9780871692498. Cited on page 49 of Kritsky, Gene (2004). Hoffmann, Nancy E.; Van Horne, John C (eds.). John Bartram and the Periodical Cicadas: A Case Study. America's Curious Botanist: A Tercentennial Reappraisal of John Bartram 1699-1777. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The American Philosophical Society. pp. 43–51. ISBN 9780871692498. Retrieved 2017-05-21 – via Google Books.

Moreover, the first time the Society had heard about periodical cicadas was from Paul Dudley, who sent a manuscript to the Society in 1733. .... Dudley correctly noted the seventeen-year life cycle and provided evidence. However, Collinson's paper shows that he used Bartram's claim of a fifteen-year cycle in his paper.

- Davis, J.J. (May 1953). "Pehr Kalm's Description of the Periodical Cicada, Magicicada septendecim L., from Kongl. Svenska Vetenskap Academiens Handlinger, 17:101-116, 1756, translated by Larson, Esther Louise (Mrs. K.E. Doak)". The Ohio Journal of Science. 53: 139–140. hdl:1811/4028. Republished by Knowledge Bank: The Ohio State University Libraries and Office of the Chief Information Officer. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- Kalm, Peter (1771). Travels into North America: Translated into English, By John Reinhold Foster. 2. London: T. Lowndess. pp. 212–213. Retrieved 2017-05-21 – via Google Books.

- Kalm, Peter (1771). Travels into North America: Translated into English, By John Reinhold Foster. 2. London: T. Lowndess. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2017-05-21 – via Google Books.

- Linnaei, Caroli (1758). Insecta. Hemiptera. Cicada. Mannifera. septendecim. Systema Naturae Per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. 1 (10th ed.). Stockholm, Sweden: Laurentii Salvii. pp. 436–437. Retrieved 2017-05-24 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL).

- Bartram, Moses (1766). Observations on the cicada, or locust of America, which appears periodically once in 16 or 17 years. Communicated by the ingenious Peter Collinson, Esq. The Annual Register, or a View of the History, Politicks, and Literature, for the Year 1767. London: Printed for J. Dodsley (1768). pp. 103–106. OCLC 642534652. Retrieved 2017-05-21 – via Google Books.

- Jefferson, Thomas (1775). Betts, Edward Morris (ed.). "Thomas Jefferson's garden book, 1766-1824, with relevant extracts from his other writings". Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society (1944). 22: 68. LCCN 45001776. OCLC 602659598. Retrieved 2017-05-20 – via Google Books.

Dr. Walker sais he remembers that the years 1724 and 1741 were great locust years. we all remember that 1758 was and now they are come again this year of 1775. it appears that they come periodically from the ground once in 17 years. they come out of the ground from a prodigious depth. it is thought they eat nothing while in this state, laying their eggs in the small twigs of trees seems to be their only business. The females make a noise well known. The males are silent.

- (1) Latrobe, John H. B., Esq. (1845). Memoir of Benjamin Banneker: Read before the Maryland Historical Society at the Monthly Meeting, May 1, 1845. Baltimore, Maryland: Printed by John D. Toy. pp. 11–12. OCLC 568468091. Retrieved 2015-10-07 – via Google Books.

(2) Barber, Janet E.; Nkwanta, Asamoah (2014). "Benjamin Banneker's Original Handwritten Document: Observations and Study of the Cicada". Journal of Humanistic Mathematics. 4 (1): 112–114. doi:10.5642/jhummath.201401.07. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

External links

Media related to Magicicada septemdecim at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magicicada septemdecim at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Magicicada septemdecim at Wikispecies

Data related to Magicicada septemdecim at Wikispecies