Malaise era

Malaise Era is a term describing U.S. market cars from roughly 1973 to 1983[2][3] during which they suffered from very poor performance.[4] The U.S. Federal Government was mandating technologies that increased fuel usage, while also mandating that fuel usage decrease.[5][6][7][8]

Pre-Malaise

Until this time the automotive industry in the United States had relied on powerful but inefficient engines to drive the typically large and heavy vehicles. For example, in 1971 the popular base model Chevrolet Caprice’s standard engine was a powerful 190 kW (255 hp) 400-cubic-inch (6.6 L) V8, with which it attained a fuel efficiency rating of 11.2 miles per US gallon (21.0 l/100 km) and a top speed of 176 km/h (109 mph).[9]

Mandates and Crisis

The period began with the 1973 oil crisis, by the end of which, in March 1974, the price of oil had nearly quadrupled, from US$3 per barrel to nearly $12 globally; US prices were significantly higher.[11] The result was a sudden switch in consumer taste from traditional US gas-guzzlers to more efficient compact cars. Since the US manufacturers had few of these products, European and Japanese models increased their market share.[12]

Also, car manufacturers used primitive technologies to address emissions control in the US. By the 1974 model year, the emission standards had tightened such that the de-tuning techniques used to meet them were seriously reducing engine efficiency and thus increasing fuel usage. The new emission standards for the 1975 model year and the increase in fuel usage forced the invention of the catalytic converter.

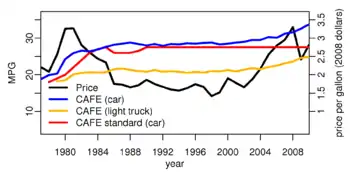

The United States Environmental Protection Agency then regulated for fuel efficiency through the vehicle emissions control, and in 1978 the Energy Tax Act legislated to discourage the sale of new inefficient vehicles, via the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standard.[7]

The United States did not sign the United Nations 1958 World Forum for Harmonization of Vehicle Regulations, the relevant agency charged with implementing CAFE standard so the NHTSA followed the precautionary principle, also used by the Food and Drug Administration, where innovations are prohibited until their developers can spend vast amounts of money to prove them safe to the regulators.[13] Issues that concern automotive engineers, like weight and aerodynamics, were not top priority for the regulators.[13]

An illustrative example was Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 108 which effectively banned headlights that did not conform to DOT-approved sealed beam design parameters that had been established in 1940,[14] so composite headlamps with aerodynamic designs that could not accommodate sealed beam-specific adjusting apparatus were illegal.[15][16] Based on legislation that dated from 1940, all automobiles sold in the U.S. were required to have round, sealed-beam headlamps that produced 75,000 candlepower.[17][18] These laws are often described by automotive journalists as "stupid" and "archaic" due to their detrimental effect on automotive function.[15][16][19][20] This resulted in such oddities as the banning of the Citroën DS's quartz iodine halogen swiveling headlamps designed for the 1968 model.[21] Even aerodynamic headlight covers, featured on other cars such as the Jaguar E-Type were illegal and had to be removed. Due to the conflicting pressure of fuel efficient aerodynamics, the regulators were forced to relent somewhat in 1983.[16]

From 1973 to 1982, NHTSA also imposed a weight increasing 5 mph (8.0 km/h) bumper regulation on American motorists, to alleviate minor damage from low speed impacts.[5][6][22] Extra weight causes an increase in gasoline usage.[23]

In 2002, a committee of the National Academy of Sciences explored the tradeoffs of CAFE, finding that motor vehicle fuel consumption would have been approximately 14 percent higher than it was in 2002 without CAFE. Fatalities would be lower, estimated between 1,300 to 2,600 in 1993.[24]

In 1979, oil and gas prices again increased significantly, doubling over 12 months, and there was a further shift in customer preference to smaller, more efficient vehicles. American automakers began introducing smaller, less powerful models to compete against, particularly the Japanese offerings.[25]

End

The "Malaise era" ended between 1983, with the advent of computer controlled vehicles, electronic fuel injection, the oxygen sensor, and three-way catalyst, and 1996, when OBD II computer controls were mandated federally.[26] The fuel crisis receded further into history during the 1980's and performance was no longer a dirty word, according to Hagerty (Insurance).[27] In 1985, Mustang horsepower climbed above 200 for the first time since the early 1970s.[27] The Malaise Era might have finally ended when the national speed limit was raised to 65 mph in 1987.[27]

Views on Era

.jpg.webp)

The phrase, coined by journalist Murilee Martin,[2] refers to US President Jimmy Carter's malaise speech in which he discussed America's failure to deal with the 1979 oil crisis.

Other journalists noted the slow and ugly vehicles offered to Americans in this era.[28][29]

Ford Motor Company explained that this was a period that had to be endured. For example, the Ford Pinto-based Mustang II was a necessary step for the survival of the Mustang nameplate.[30]

Some see a bright side, noting innovations in factory tape application kits, such as the second generation Pontiac Trans Am, with its massive Screaming Chicken hood sticker, the 1978 Mustang King Cobra hood sticker, and AMC Gremlin GT's matte stripe fender flares that dwarfed the 14-inch rally wheels.[3]

See also

References

- https://www.automobile-catalog.com/make/chrysler/full-size_chrysler_8gen/full-size_8gen_newport_sedan/1979.html

- Rood, Eric (20 March 2017). "Tonnage: 10 Gigantic Malaise-Era Land Yachts". Roadkill. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Daniel Strohl (14 March 2013). "Ten reasons to love the Malaise Era". Hemmings Motor News.

- Stewart, Ben (10 September 2012). "Performance Pretenders: 10 Malaise-Era Muscle Cars". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "A short history of the Pontiac Firebird". Haynes.

- Solomon, Jack (March 1978). "Billion Dollar Bumpers". Reason.

- Baruch Feigenbaum; Julian Morris. "CAFE Standards in Plain English" (PDF). Reason.

- "A Brief History of US Fuel Efficiency Standards Where we are—and where are we going?". The Union of Concerned Scientists is a national nonprofit organization founded more than 50 years ago by scientists and students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 25 July 2006.

- "1971 Chevrolet (USA) Caprice Hardtop Sedan on Automobile Catalog". Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- https://www.automobile-catalog.com/make/ford_usa/mustang_2gen_ii/mustang_2gen_ii_ghia/1977.html

- "OPEC Oil Embargo 1973–1974". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- Sawyers, Arlena (13 October 2013). "1979 oil shock meant recession for U.S., depression for autos". Automotive News. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- L. Gordon Crovitz (21 August 2016). "Humans: Unsafe at Any Speed". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- Josh Weinstein (27 May 2020). "Sealed Beam Headlights and Why They Changed".

- REED HITCHCOCK (27 March 2012). "Fleet Report: 1983 Mercedes-Benz 300DT – Let There Be Bright!".

- "Light Up My Journey". 9 July 2016.

- Whitely, Peyton (24 April 1992). "How Bright Really Right in Today's Headlight?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- Greiling Keane, Angela (28 March 2013). "Audi Wants to Change a 45-Year-Old U.S. Headlight Rule". BloombergBusinessweek. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- cite web|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070104231250/http://vintagecars.about.com/od/historygreatmoments/a/citroen_ds.htm%7Ctitle%3D20 Years Later it Was Still Ahead. When Would the Others Catch Up?|date=2007|publisher=About, Inc., A part of The New York Times Company}}

- "Audi Challenging US Headlight Rule". 24 April 2013.

- Ronan Glon (4 April 2014). "Classic: The History of the Citroën DS - The DS in North America". Winding Road Media, LLC-NextScreen, LLC.

- Corey Lewis (28 February 2018). "QOTD: Can We Inventory the Worst Bumpers of the 1970s?". The Truth About Cars.

- JEAN FOLGER (25 June 2019). "9 Easy Ways To Increase Your Gas Mileage".

- "Effectiveness and Impact of Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) Standards". Books.nap.edu. 2001-07-01. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- "1979 oil shock meant recession for U.S., depression for autos / 100 Events That Made the Industry". Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- "These Two Ads Show Why The Malaise Era Was Never Necessary". Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- Rob Sass (1 August 2013). "Heavier. Slower. Safer". The Hagerty Group, LLC.

- Aaron Gold (10 April 2020). "The Ugliest Cars of the 1970s In a decade of dreadful design, some cars were worse than others". Automobile Magazine.

- Tyler Hoover (9 February 2017). "A Tale of Two Mercedes: When the Grey Market Made U.S.-Spec Cars Compete With Euro Models". Autotrader.

- "Mustang II Forty Years Later". Ford Media Center, a division of Ford Motor Company. 17 September 2013.