Malaysia

Malaysia (/məˈleɪziə, -ʒə/ (![]() listen) mə-LAY-zee-ə, -zhə; Malay: [məlejsiə]) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions, Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Malaysia. Peninsular Malaysia shares a land and maritime border with Thailand and maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia. East Malaysia shares land and maritime borders with Brunei and Indonesia and a maritime border with the Philippines and Vietnam. Kuala Lumpur is the national capital and largest city while Putrajaya is the seat of the federal government. With a population of over 32 million, Malaysia is the world's 43rd-most populous country. The southernmost point of continental Eurasia is in Tanjung Piai. In the tropics, Malaysia is one of 17 megadiverse countries, home to a number of endemic species.

listen) mə-LAY-zee-ə, -zhə; Malay: [məlejsiə]) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federal constitutional monarchy consists of thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two regions, Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo's East Malaysia. Peninsular Malaysia shares a land and maritime border with Thailand and maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia. East Malaysia shares land and maritime borders with Brunei and Indonesia and a maritime border with the Philippines and Vietnam. Kuala Lumpur is the national capital and largest city while Putrajaya is the seat of the federal government. With a population of over 32 million, Malaysia is the world's 43rd-most populous country. The southernmost point of continental Eurasia is in Tanjung Piai. In the tropics, Malaysia is one of 17 megadiverse countries, home to a number of endemic species.

Malaysia | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp)  | |

| Capital | Kuala Lumpur 3°8′N 101°41′E Putrajaya (administrative) 2.9430952°N 101.699373°E |

| Largest city | Kuala Lumpur |

Official language and national language | Malay[n 1][n 2][n 3] |

| Recognised language | English[n 3] |

| Ethnic groups (2018)[2] |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Malaysian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary constitutional elective monarchy |

| Abdullah al-Haj[5] | |

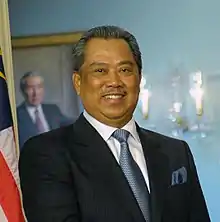

| Muhyiddin Yassin | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Dewan Negara (Senate) | |

| Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 31 August 1957[6] | |

| 22 July 1963 | |

| 31 August 1963 | |

| 16 September 1963 | |

| 9 August 1965 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 330,803 km2 (127,724 sq mi) (66th) |

• Water (%) | 0.3 |

| Population | |

• Q1 2020 estimate | |

• 2010 census | 28,334,135[8] |

• Density | 92/km2 (238.3/sq mi) (116th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2015) | medium |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 62nd |

| Currency | Ringgit (RM) (MYR) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (MST) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +60 |

| ISO 3166 code | MY |

| Internet TLD | .my |

Malaysia has its origins in the Malay kingdoms which, from the 18th century, became subject to the British Empire, along with the British Straits Settlements protectorate. Peninsular Malaysia was unified as the Malayan Union in 1946. Malaya was restructured as the Federation of Malaya in 1948 and achieved independence on 31 August 1957. Malaya united with North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore on 16 September 1963 to become Malaysia. In 1965, Singapore was expelled from the federation.[12]

The country is multi-ethnic and multi-cultural, which has a significant effect on its politics. About half the population is ethnically Malay, with minorities of Chinese, Indians, and indigenous peoples. The country's official language is Malaysian, a standard form of the Malay language. English remains an active second language. While recognising Islam as the country's established religion, the constitution grants freedom of religion to non-Muslims. The government is modelled on the Westminster parliamentary system and the legal system is based on common law. The head of state is an elected monarch, chosen from among the nine state sultans every five years. The head of government is the Prime Minister.

After independence, the Malaysian GDP grew at an average of 6.5% per annum for almost 50 years. The economy has traditionally been fuelled by its natural resources but is expanding in the sectors of science, tourism, commerce and medical tourism. Malaysia has a newly industrialised market economy, ranked third-largest in Southeast Asia and 33rd-largest in the world.[13] It is a founding member of ASEAN, EAS, OIC and a member of APEC, the Commonwealth and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Etymology

The name "Malaysia" is a combination of the word "Malays" and the Latin-Greek suffix "-ia"/"-ία"[14] which can be translated as "land of the Malays".[15] The origin of the word 'Melayu' is subject to various theories. It may derive from the Sanskrit "Himalaya", referring to areas high in the mountains, or "Malaiyur-pura", meaning mountain town.[16] Another similar theory claims its origin lies in the Tamil words "malai" and "ur" meaning "mountain" and "city, land", respectively.[17][18][19] Another suggestion is that it derives from the Pamalayu campaign. A final suggestion is that it comes from a Javanese word meaning "to run", from which a river, the Sungai Melayu ('Melayu river'), was named due to its strong current.[16] Similar-sounding variants have also appeared in accounts older than the 11th century, as toponyms for areas in Sumatra or referring to a larger region around the Strait of Malacca.[20] The Sanskrit text Vayu Purana, thought to have been in existence since the first millennium CE, mentioned a land named 'Malayadvipa' which was identified by certain scholars as the modern Malay peninsula.[21][22][23][24][25] Other notable accounts are by the 2nd century Ptolemy's Geographia that used the name Malayu Kulon for the west coast of Golden Chersonese, and the 7th century Yijing's account of Malayu.[20]

At some point, the Melayu Kingdom took its name from the Sungai Melayu.[16][26] 'Melayu' then became associated with Srivijaya,[20] and remained associated with various parts of Sumatra, especially Palembang, where the founder of the Malacca Sultanate is thought to have come from.[27] It is only thought to have developed into an ethnonym as Malacca became a regional power in the 15th century. Islamisation established an ethnoreligious identity in Malacca, with the term 'Melayu' beginning to appear as interchangeable with 'Melakans'. It may have specifically referred to local Malays speakers thought loyal to the Malaccan Sultan. The initial Portuguese use of Malayos reflected this, referring only to the ruling people of Malacca. The prominence of traders from Malacca led 'Melayu' to be associated with Muslim traders, and from there became associated with the wider cultural and linguistic group.[20] Malacca and later Johor claimed they were the centre of Malay culture, a position supported by the British which led to the term 'Malay' becoming more usually linked to the Malay peninsula rather than Sumatra.[27]

Before the onset of European colonisation, the Malay Peninsula was known natively as "Tanah Melayu" ("Malay Land").[28][29] Under a racial classification created by a German scholar Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, the natives of maritime Southeast Asia were grouped into a single category, the Malay race.[30][31] Following the expedition of French navigator Jules Dumont d'Urville to Oceania in 1826, he later proposed the terms of "Malaysia", "Micronesia" and "Melanesia" to the Société de Géographie in 1831, distinguishing these Pacific cultures and island groups from the existing term "Polynesia". Dumont d'Urville described Malaysia as "an area commonly known as the East Indies".[32] In 1850, the English ethnologist George Samuel Windsor Earl, writing in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, proposed naming the islands of Southeast Asia as "Melayunesia" or "Indunesia", favouring the former.[33] The name Malaysia gained some use to label what is now the Malay Archipelago.[34] In modern terminology, "Malay" remains the name of an ethnoreligious group of Austronesian people predominantly inhabiting the Malay Peninsula and portions of the adjacent islands of Southeast Asia, including the east coast of Sumatra, the coast of Borneo, and smaller islands that lie between these areas.[35]

The state that gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1957 took the name the "Federation of Malaya", chosen in preference to other potential names such as "Langkasuka", after the historic kingdom located at the upper section of the Malay Peninsula in the first millennium CE.[36][37] The name "Malaysia" was adopted in 1963 when the existing states of the Federation of Malaya, plus Singapore, North Borneo and Sarawak formed a new federation.[38] One theory posits the name was chosen so that "si" represented the inclusion of Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak to Malaya in 1963.[38] Politicians in the Philippines contemplated renaming their state "Malaysia" before the modern country took the name.[39]

History

Evidence of modern human habitation in Malaysia dates back 40,000 years.[40] In the Malay Peninsula, the first inhabitants are thought to be Negritos.[41] Traders and settlers from India and China arrived as early as the first century AD, establishing trading ports and coastal towns in the second and third centuries. Their presence resulted in strong Indian and Chinese influences on the local cultures, and the people of the Malay Peninsula adopted the religions of Hinduism and Buddhism. Sanskrit inscriptions appear as early as the fourth or fifth century.[42] The Kingdom of Langkasuka arose around the second century in the northern area of the Malay Peninsula, lasting until about the 15th century.[36] Between the 7th and 13th centuries, much of the southern Malay Peninsula was part of the maritime Srivijayan empire. By the 13th and the 14th century, the Majapahit empire had successfully wrested control over most of the peninsula and the Malay Archipelago from Srivijaya.[43] Islam began to spread among Malays in the 14th century.[44] In the early 15th century, Parameswara, a runaway king of the former Kingdom of Singapura linked to the old Srivijayan court, founded the Malacca Sultanate. Malacca was an important commercial centre during this time, attracting trade from around the region.

In 1511, Malacca was conquered by Portugal,[44] after which it was taken by the Dutch in 1641. In 1786, the British Empire established a presence in Malaya, when the Sultan of Kedah leased Penang Island to the British East India Company. The British obtained the town of Singapore in 1819,[45] and in 1824 took control of Malacca following the Anglo-Dutch Treaty. By 1826, the British directly controlled Penang, Malacca, Singapore, and the island of Labuan, which they established as the crown colony of the Straits Settlements. By the 20th century, the states of Pahang, Selangor, Perak, and Negeri Sembilan, known together as the Federated Malay States, had British residents appointed to advise the Malay rulers, to whom the rulers were bound to defer by treaty.[46] The remaining five states in the peninsula, known as the Unfederated Malay States, while not directly under British rule, also accepted British advisers around the turn of the 20th century. Development on the peninsula and Borneo were generally separate until the 19th century. Under British rule the immigration of Chinese and Indians to serve as labourers was encouraged.[47] The area that is now Sabah came under British control as North Borneo when both the Sultan of Brunei and the Sultan of Sulu transferred their respective territorial rights of ownership, between 1877 and 1878.[48] In 1842, Sarawak was ceded by the Sultan of Brunei to James Brooke, whose successors ruled as the White Rajahs over an independent kingdom until 1946, when it became a crown colony.[49]

.jpg.webp)

In the Second World War, the Japanese Army invaded and occupied Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore for over three years. During this time, ethnic tensions were raised and nationalism grew.[50] Popular support for independence increased after Malaya was reconquered by Allied forces.[51] Post-war British plans to unite the administration of Malaya under a single crown colony called the "Malayan Union" met with strong opposition from the Malays, who opposed the weakening of the Malay rulers and the granting of citizenship to the ethnic Chinese. The Malayan Union, established in 1946, and consisting of all the British possessions in the Malay Peninsula with the exception of Singapore, was quickly dissolved and replaced on 1 February 1948 by the Federation of Malaya, which restored the autonomy of the rulers of the Malay states under British protection.[52] During this time, mostly Chinese rebels under the leadership of the Malayan Communist Party launched guerrilla operations designed to force the British out of Malaya. The Malayan Emergency lasted from 1948 to 1960, and involved a long anti-insurgency campaign by Commonwealth troops in Malaya.[53] On 31 August 1957, Malaya became an independent member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[54] After this a plan was put in place to federate Malaya with the crown colonies of North Borneo (which joined as Sabah), Sarawak, and Singapore. The date of federation was planned to be 31 August 1963 so as to coincide with the anniversary of Malayan independence; however, federation was delayed until 16 September 1963 in order for a United Nations survey of support for federation in Sabah and Sarawak, called for by parties opposed to federation including Indonesia's Sukarno and the Sarawak United Peoples' Party, to be completed.[55][56]

Federation brought heightened tensions including a conflict with Indonesia as well continuous conflicts against the Communists in Borneo and the Malayan Peninsula which escalates to the Sarawak Communist Insurgency and Second Malayan Emergency together with several other issues such as the cross border attacks into North Borneo by Moro pirates from the southern islands of the Philippines, Singapore being expelled from the Federation in 1965,[57][58] and racial strife. This strife culminated in the 13 May race riots in 1969.[59] After the riots, the controversial New Economic Policy was launched by Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak, trying to increase the share of the economy held by the bumiputera.[60] Under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad there was a period of rapid economic growth and urbanisation beginning in the 1980s. The economy shifted from being agriculturally based to one based on manufacturing and industry. Numerous mega-projects were completed, such as the Petronas Towers, the North–South Expressway, the Multimedia Super Corridor, and the new federal administrative capital of Putrajaya.[38] However, in the late 1990s the Asian financial crisis almost caused the collapse of the currency and the stock and property markets.[61]

Government and politics

_2.jpg.webp)

Malaysia is a federal constitutional elective monarchy; the only federal country in Southeast Asia.[62] The system of government is closely modelled on the Westminster parliamentary system, a legacy of British rule.[63] The head of state is the King, whose official title is the Yang di-Pertuan Agong. The King is elected to a five-year term by and from among the nine hereditary rulers of the Malay states. The other four states, which have titular Governors, do not participate in the selection. By informal agreement the position is rotated among the nine,[63] and has been held by Abdullah of Pahang since 31 January 2019.[64] The King's role has been largely ceremonial since changes to the constitution in 1994, picking ministers and members of the upper house.[65]

Legislative power is divided between federal and state legislatures. The bicameral federal parliament consists of the lower house, the House of Representatives and the upper house, the Senate.[66] The 222-member House of Representatives is elected for a maximum term of five years from single-member constituencies. All 70 senators sit for three-year terms; 26 are elected by the 13 state assemblies, and the remaining 44 are appointed by the King upon the Prime Minister's recommendation.[44] The parliament follows a multi-party system and the government is elected through a first-past-the-post system.[44][67] Parliamentary elections are held at least once every five years,[44] the most recent of which took place in May 2018.[68] Before 2018, registered voters aged 21 and above could vote for the members of the House of Representatives and, in most of the states, for the state legislative chamber. Voting is not mandatory.[69] In July 2019, a bill to lower the voting age to 18 years old was officially passed.[70] Malaysia's ranking increased by 9 places in the 2019 Democracy Index to 43th compared to the previous year, and is classified as a 'flawed democracy'.[71]

Executive power is vested in the Cabinet, led by the Prime Minister. The prime minister must be a member of the House of Representatives, who in the opinion of His Majesty the King, commands the support of a majority of members. The Cabinet is chosen from members of both houses of Parliament.[44] The Prime Minister is both the head of cabinet and the head of government.[65] As a result of the 2018 general election Malaysia was governed by the Pakatan Harapan political alliance,[68] however on 24 February 2020 Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad resigned. On 1 March 2020, a new coalition governed Malaysia led by a new 8th Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin.[72]

Malaysia's legal system is based on English Common Law.[44] Although the judiciary is theoretically independent, its independence has been called into question and the appointment of judges lacks accountability and transparency.[73] The highest court in the judicial system is the Federal Court, followed by the Court of Appeal and two high courts, one for Peninsular Malaysia and one for East Malaysia. Malaysia also has a special court to hear cases brought by or against royalty.[74] The death penalty is in use for serious crimes such as murder, terrorism, drug trafficking, and kidnapping.[75][76] Separate from and running parallel to the civil courts[77] are the Syariah Courts, which apply Shariah law to Muslims[78] in the areas of family law and religious observances. Homosexuality is illegal in Malaysia,[79][80] and the authorities can impose punishment such as caning.[81] Human trafficking and sex trafficking in Malaysia are significant problems.[82][83]

Race is a significant force in politics.[44] Affirmative actions such as the New Economic Policy[60] and the National Development Policy which superseded it, were implemented to advance the standing of the bumiputera, consisting of Malays and the indigenous tribes who are considered the original inhabitants of Malaysia, over non-bumiputera such as Malaysian Chinese and Malaysian Indians.[84] These policies provide preferential treatment to bumiputera in employment, education, scholarships, business, and access to cheaper housing and assisted savings. However, it has generated greater interethnic resentment.[85] There is ongoing debate over whether the laws and society of Malaysia should reflect secular or Islamic principles.[86] Islamic criminal laws passed by the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party with the support of United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) state assemblymen in the state legislative assembly of Kelantan have been blocked by the federal government on the basis that criminal laws are the responsibility of the federal government.[87][88][89]

Malaysia's ranking in the 2020 Press Freedom Index increased by 22 places to 101th compared to the previous year, making it one of two countries in Southeast Asia without a 'Difficult situation' or 'Very Serious situation' with regards to press freedom.[90] Malaysia is marked in the 50–59 range according to the 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index, indicating a moderate level of corruption. Freedom House noted Malaysia as "partly free" in its 2018 survey.[91] A lawsuit filed by Department of Justice (DOJ), alleged that at least $3.5 billion has been stolen from Malaysia's 1MDB state-owned fund.[92][93][94] On 28 July 2020, former Prime Minister Najib Razak was found guilty on seven charges in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad scandal.[95] He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.[96]

Administrative divisions

.png.webp)

(Red) Federal Territories

|

Malaysia is a federation of 13 states and three federal territories.[97] These are divided between two regions, with 11 states and two federal territories on Peninsular Malaysia and the other two states and one federal territory in East Malaysia. Each state is divided into districts, which are then divided into mukim. In Sabah and Sarawak districts are grouped into divisions.[98]

Governance of the states is divided between the federal and the state governments, with different powers reserved for each, and the Federal government has direct administration of the federal territories.[99] Each state has a unicameral State Legislative Assembly whose members are elected from single-member constituencies. State governments are led by Chief Ministers,[44] who are state assembly members from the majority party in the assembly. In each of the states with a hereditary ruler, the Chief Minister is normally required to be a Malay, appointed by the ruler upon the recommendation of the Prime Minister.[100] Except for state elections in Sarawak, by convention state elections are held concurrently with the federal election.[65]

Lower-level administration is carried out by local authorities, which include city councils, district councils, and municipal councils, although autonomous statutory bodies can be created by the federal and state governments to deal with certain tasks.[101] The federal constitution puts local authorities outside of the federal territories under the exclusive jurisdictions of the state government,[102] although in practice the federal government has intervened in the affairs of state local governments.[103] There are 154 local authorities, consisting of 14 city councils, 38 municipal councils, and 97 district councils.

The 13 states are based on historical Malay kingdoms, and 9 of the 11 Peninsular states, known as the Malay states, retain their royal families. The King is elected by and from the nine rulers to serve a five-year term.[44] This King appoints governors serving a four-year term for the states without monarchies, after consultations with the chief minister of that state. Each state has its own written constitution.[104] Sabah and Sarawak have considerably more autonomy than the other states, most notably having separate immigration policies and controls, and a unique residency status.[105][106][107] Federal intervention in state affairs, lack of development, and disputes over oil royalties have occasionally led to statements about secession from leaders in several states such as Penang, Johor, Kelantan, Sabah and Sarawak, although these have not been followed up and no serious independence movements exist.[108][109][110][111]

- States

A list of thirteen states and each state capital (in brackets):

- Federal Territories

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

A founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)[112] and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC),[113] the country participates in many international organisations such as the United Nations,[114] the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation,[115] the Developing 8 Countries,[116] and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).[117] It has chaired ASEAN, the OIC, and the NAM in the past.[44] A former British colony, it is also a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[118] Kuala Lumpur was the site of the first East Asia Summit in 2005.[119]

Malaysia's foreign policy is officially based on the principle of neutrality and maintaining peaceful relations with all countries, regardless of their political system.[120] The government attaches a high priority to the security and stability of Southeast Asia,[119] and seeks to further develop relations with other countries in the region. Historically the government has tried to portray Malaysia as a progressive Islamic nation[120] while strengthening relations with other Islamic states.[119] A strong tenet of Malaysia's policy is national sovereignty and the right of a country to control its domestic affairs.[65] Malaysia signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[121][122]

The Spratly Islands are disputed by many states in the area, and a large portion of the South China Sea is claimed by China. Unlike its neighbours of Vietnam and the Philippines, Malaysia historically avoided conflicts with China.[123] However, after the encroachment of Chinese ships in Malaysian territorial waters,[124] Malaysia has become active in condemning China.[125][126] Brunei and Malaysia in 2009 announced an end to claims of each other's land, and committed to resolve issues related to their maritime borders.[127] The Philippines has a dormant claim to the eastern part of Sabah.[128] Singapore's land reclamation has caused tensions,[129] and minor maritime and land border disputes exist with Indonesia.[128][130]

Malaysia has never recognised Israel and has no diplomatic ties with it,[131] and has called for the International Criminal Court to take action against Israel over its Gaza flotilla raid.[132] Malaysia has stated it will establish official relations with Israel only when a peace agreement with the State of Palestine has been reached, and called for both parties to find a quick resolution to realise the two-state solution.[131][133][134][135]

Military

The Malaysian Armed Forces have three branches: the Royal Malaysian Navy, the Malaysian Army, and the Royal Malaysian Air Force. There is no conscription, and the required age for voluntary military service is 18. The military uses 1.5% of the country's GDP, and employs 1.23% of Malaysia's manpower.[136]

The Five Power Defence Arrangements is a regional security initiative which has been in place for almost 40 years. It involves joint military exercises held among Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.[137] Joint exercises and war games have also been held with Brunei,[138] China,[139] India,[140] Indonesia[141] Japan[142] and the United States.[143] Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam have agreed to host joint security force exercises to secure their maritime border and tackle issues such as illegal immigration, piracy and smuggling.[144][145][146] Previously there were fears that extremist militants activities in the Muslim areas of the southern Philippines[147] and southern Thailand[148] would spill over into Malaysia. Because of this, Malaysia began to increase its border security.[147]

Malaysian peacekeeping forces have contributed to many UN peacekeeping missions, such as in Congo, Iran–Iraq, Namibia, Cambodia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somalia, Kosovo, East Timor and Lebanon.[44][149]

Geography

.PNG.webp)

Malaysia is the 66th largest country by total land area, with a land area of 329,613 km2 (127,264 sq mi). It has land borders with Thailand in West Malaysia, and Indonesia and Brunei in East Malaysia.[150] It is linked to Singapore by a narrow causeway and a bridge. The country also has maritime boundaries with Vietnam[151] and the Philippines.[152] The land borders are defined in large part by geological features such as the Perlis River, the Golok River and the Pagalayan Canal, whilst some of the maritime boundaries are the subject of ongoing contention.[150] Brunei forms what is almost an enclave in Malaysia,[153] with the state of Sarawak dividing it into two parts. Malaysia is the only country with territory on both the Asian mainland and the Malay archipelago.[154] Tanjung Piai, located in the southern state of Johor, is the southernmost tip of continental Asia.[155] The Strait of Malacca, lying between Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia, is one of the most important thoroughfares in global commerce, carrying 40 per cent of the world's trade.[156]

The two parts of Malaysia, separated from each other by the South China Sea, share a largely similar landscape in that both Peninsular and East Malaysia feature coastal plains rising to hills and mountains.[150] Peninsular Malaysia, containing 40 per cent of Malaysia's land area,[154] extends 740 km (460 mi) from north to south, and its maximum width is 322 km (200 mi).[157] It is divided between its east and west coasts by the Titiwangsa Mountains,[158] rising to a peak elevation of 2,183 metres (7,162 ft) at Mount Korbu,[159] part of a series of mountain ranges running down the centre of the peninsula.[154] These mountains are heavily forested,[160] and mainly composed of granite and other igneous rocks. Much of it has been eroded, creating a karst landscape.[154] The range is the origin of some of Peninsular Malaysia's river systems.[160] The coastal plains surrounding the peninsula reach a maximum width of 50 kilometres (31 mi), and the peninsula's coastline is nearly 1,931 km (1,200 mi) long, although harbours are only available on the western side.[157]

East Malaysia, on the island of Borneo, has a coastline of 2,607 km (1,620 mi).[150] It is divided between coastal regions, hills and valleys, and a mountainous interior.[154] The Crocker Range extends northwards from Sarawak,[154] dividing the state of Sabah. It is the location of the 4,095 m (13,435 ft) high Mount Kinabalu,[161][162] the tallest mountain in Malaysia. Mount Kinabalu is located in the Kinabalu National Park, which is protected as one of the four UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Malaysia.[163] The highest mountain ranges form the border between Malaysia and Indonesia. Sarawak contains the Mulu Caves, the largest cave system in the world, in the Gunung Mulu National Park which is also a World Heritage Site.[154]

Around these two halves of Malaysia are numerous islands, the largest of which is Banggi.[164] The local climate is equatorial and characterised by the annual southwest (April to October) and northeast (October to February) monsoons.[157] The temperature is moderated by the presence of the surrounding oceans.[154] Humidity is usually high, and the average annual rainfall is 250 cm (98 in).[157] The climates of the Peninsula and the East differ, as the climate on the peninsula is directly affected by wind from the mainland, as opposed to the more maritime weather of the East. Local climates can be divided into three regions, highland, lowland, and coastal. Climate change is likely to affect sea levels and rainfall, increasing flood risks and leading to droughts.[154]

Biodiversity

Malaysia signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 12 June 1993, and became a party to the convention on 24 June 1994.[165] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 16 April 1998.[166] The country is megadiverse with a high number of species and high levels of endemism.[167] It is estimated to contain 20 per cent of the world's animal species.[168] High levels of endemism are found on the diverse forests of Borneo's mountains, as species are isolated from each other by lowland forest.[154] There are about 210 mammal species in the country.[161] Over 620 species of birds have been recorded in Peninsular Malaysia,[168] with many endemic to the mountains there. A high number of endemic bird species are also found in Malaysian Borneo.[154] 250 reptile species have been recorded in the country, with about 150 species of snakes[169] and 80 species of lizards.[161] There are about 150 species of frogs,[161] and thousands of insect species.[161] The Exclusive economic zone of Malaysia is 334,671 km2 (129,217 sq mi) and 1.5 times larger than its land area. It is mainly in the South China Sea.[170][171] Some of its waters are in the Coral Triangle, a biodiversity hotspot.[172] The waters around Sipadan island are the most biodiverse in the world.[168] Bordering East Malaysia, the Sulu Sea is a biodiversity hotspot, with around 600 coral species and 1200 fish species.[173] The unique biodiversity of Malaysian Caves always attracts lovers of ecotourism from all over the world.[174]

Nearly 4,000 species of fungi, including lichen-forming species have been recorded from Malaysia. Of the two fungal groups with the largest number of species in Malaysia, the Ascomycota and their asexual states have been surveyed in some habitats (decaying wood, marine and freshwater ecosystems, as parasites of some plants, and as agents of biodegradation), but have not been or have been only poorly surveyed in other habitats (as endobionts, in soils, on dung, as human and animal pathogens); the Basidiomycota are only partly surveyed: bracket fungi, and mushrooms and toadstools have been studied, but Malaysian rust and smut fungi remain very poorly known. Without doubt, many more fungal species in Malaysia have not yet been recorded, and it is likely that many of those, when found, will be new to science.[175]

About two thirds of Malaysia was covered in forest as of 2007,[157] with some forests believed to be 130 million years old.[161] The forests are dominated by dipterocarps.[176] Lowland forest covers areas below 760 m (2,490 ft),[157] and formerly East Malaysia was covered in such rainforest,[176] which is supported by its hot wet climate.[154] There are around 14,500 species of flowering plants and trees.[161] Besides rainforests, there are over 1,425 km2 (550 sq mi) of mangroves in Malaysia,[157] and a large amount of peat forest. At higher altitudes, oaks, chestnuts, and rhododendrons replace dipterocarps.[154] There are an estimated 8,500 species of vascular plants in Peninsular Malaysia, with another 15,000 in the East.[177] The forests of East Malaysia are estimated to be the habitat of around 2,000 tree species, and are one of the most biodiverse areas in the world, with 240 different species of trees every hectare.[154] These forests host many members of the Rafflesia genus, the largest flowers in the world,[176] with a maximum diameter of 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[178]

Conservation issues

Logging, along with cultivation practices has devastated tree cover, causing severe environmental degradation in the country. Over 80 per cent of Sarawak's rainforest has been logged.[154] Floods in East Malaysia have been worsened by the loss of trees, and over 60 per cent of the Peninsula's forest have been cleared.[178] With current rates of deforestation, mainly for the palm oil industry, the forests are predicted to be extinct by 2020.[154][179] Deforestation is a major problem for animals, fungi and plants, having caused species such as Begonia eiromischa to go extinct.[180] Most remaining forest is found inside reserves and national parks.[178] Habitat destruction has proved a threat for marine life.[173] Illegal fishing is another major threat,[173] with fishing methods such as dynamite fishing and poisoning depleting marine ecosystems.[181] Leatherback turtle numbers have dropped 98 per cent since the 1950s.[169] Hunting has also been an issue for some animals,[178] with overconsumption and the use of animal parts for profit endangering many animals, from marine life[173] to tigers.[180] Marine life is also detrimentally affected by uncontrolled tourism.[182]

The Malaysian government aims to balance economic growth with environmental protection, but has been accused of favouring big business over the environment.[178] Some state governments are now trying to counter the environmental impact and pollution created by deforestation;[176] and the federal government is trying to cut logging by 10 per cent each year. 28 national parks have been established; 23 in East Malaysia and five in the Peninsular.[178] Tourism has been limited in biodiverse areas such as Sipadan island.[182] Animal trafficking is a large issue, and the Malaysian government is holding talks with the governments of Brunei and Indonesia to standardise anti-trafficking laws.[183]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Malaysia is a relatively open state-oriented and newly industrialised market economy.[184][185] The state plays a significant but declining role in guiding economic activity through macroeconomic plans. Malaysia has had one of the best economic records in Asia, with GDP growing an average 6.5 per cent annually from 1957 to 2005.[44] Malaysia's economy in 2014–2015 was one of the most competitive in Asia, ranking 6th in Asia and 20th in the world, higher than countries like Australia, France and South Korea.[186] In 2014, Malaysia's economy grew 6%, the second highest growth in ASEAN behind the Philippines' growth of 6.1%.[187] The economy of Malaysia in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) in April 2019 was estimated to be $999.397 billion, the third largest in ASEAN and the 25th largest in the world.[188]

In 1991, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (during his first period as Prime Minister) outlined his ideal in Vision 2020, in which Malaysia would become a self-sufficient industrialised nation by 2020.[189] Najib Razak has said Malaysia could attain developed country status much earlier from the actual target in 2020, adding the country has two program concept such as Government Transformation Programme and the Economic Transformation Programme.[190] According to a HSBC report, Malaysia will become the world's 21st largest economy by 2050, with a GDP of $1.2 trillion (Year 2000 dollars) and a GDP per capita of $29,247 (Year 2000 dollars). The report also says "The electronic equipment, petroleum, and liquefied natural gas producer will see a substantial increase in income per capita. Malaysian life expectancy, relatively high level of schooling, and above average fertility rate will help in its rapid expansion".[191] Viktor Shvets, the managing director of Credit Suisse, has said "Malaysia has all the right ingredients to become a developed nation".[192]

In the 1970s, the predominantly mining and agricultural-based economy began a transition towards a more multi-sector economy. Since the 1980s, the industrial sector, with a high level of investment, has led the country's growth.[44][193] The economy recovered from the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis earlier than neighbouring countries did, and has since recovered to the levels of the pre-crisis era with a GDP per capita of $14,800.[194][195] Economic inequalities exist between different ethnic groups. The Chinese make up about one-quarter of the population, but accounts for 70 per cent of the country's market capitalisation.[196] Chinese businesses in Malaysia are part of the larger bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses in the Southeast Asian market sharing common family and cultural ties.[197]

International trade, facilitated by the shipping route in adjacent Strait of Malacca, and manufacturing are the key sectors.[198][199][200] Malaysia is an exporter of natural and agricultural resources, and petroleum is a major export.[44] Malaysia has once been the largest producer of tin,[201] rubber and palm oil in the world. Manufacturing has a large influence in the country's economy,[202] although Malaysia's economic structure has been moving away from it.[203] Malaysia remains one of the world's largest producers of palm oil.[204]

.jpg.webp)

In an effort to diversify the economy and make it less dependent on export goods, the government has pushed to increase tourism to Malaysia. As a result, tourism has become Malaysia's third largest source of foreign exchange, although it is threatened by the negative effects of the growing industrial economy, with large amounts of air and water pollution along with deforestation affecting tourism.[205] The tourism sector came under some pressure in 2014 when the national carrier Malaysia Airlines had one of its planes disappear in March, while another was brought down by a missile over Ukraine in July, resulting in the loss of a total 537 passengers and crew. The state of the airline, which had been unprofitable for 3 years, prompted the government in August 2014 to nationalise the airline by buying up the 30 per cent it did not already own.[206] Between 2013 and 2014, Malaysia has been listed as one of the best places to retire to in the world, with the country in third position on the Global Retirement Index.[207][208] This in part was the result of the Malaysia My Second Home programme to allow foreigners to live in the country on a long-stay visa for up to 10 years.[209] In 2016, Malaysia ranked the fifth position on The World's Best Retirement Havens while getting in the first place as the best place in Asia to retire. A warm climate combined with a British colonial background makes it easy for foreigners to interact with locals.[210]

The country has developed into a centre of Islamic banking, and is the country with the highest numbers of female workers in that industry.[211] Knowledge-based services are also expanding.[203] To create a self-reliant defensive ability and support national development, Malaysia privatised some of its military facilities in the 1970s. The privatisation has created defence industry, which in 1999 was brought under the Malaysia Defence Industry Council. The government continues to promote this sector and its competitiveness, actively marketing the defence industry.[212] Science policies in Malaysia are regulated by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation. The country is one of the world's largest exporters of semiconductor devices, electrical devices, and IT and communication products.[44] Malaysia began developing its own space programme in 2002,[213][214] and in 2006, Russia agreed to transport one Malaysian to the International Space Station as part of a multibillion-dollar purchase of 18 Russian Sukhoi Su-30MKM fighter jets by the Royal Malaysian Air Force.[215] The government has invested in building satellites through the RazakSAT programme.[216]

Infrastructure

Malaysia's persistent drive to develop and upgrade its infrastructure has resulted in one of the most well-developed infrastructure among the newly industrializing countries of Asia. In 2014, Malaysia ranked 8th in Asia and 25th in the world in term of overall infrastructure development.[217] The country's telecommunications network is second only to Singapore's in Southeast Asia, with 4.7 million fixed-line subscribers and more than 30 million cellular subscribers.[218][219] The country has seven international ports, the major one being the Port Klang. There are 200 industrial parks along with specialised parks such as Technology Park Malaysia and Kulim Hi-Tech Park.[220] Fresh water is available to over 95 per cent of the population with ground water accounts for 90 percent of the freshwater resources.[221][222] During the colonial period, development was mainly concentrated in economically powerful cities and in areas forming security concerns. Although rural areas have been the focus of great development, they still lag behind areas such as the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia.[223] The telecommunication network, although strong in urban areas, is less available to the rural population.[218]

Malaysia's energy infrastructure sector is largely dominated by Tenaga Nasional, the largest electric utility company in Southeast Asia, with over RM99.03 billion of assets. Customers are connected to electricity through the National Grid, with more than 420 transmission substations in the Peninsular linked together by approximately 11,000 km of transmission lines operating at 66, 132, 275, and 500 kilovolts.[224] The other two electric utility companies in the country are Sarawak Energy and Sabah Electricity.[225] In 2013, Malaysia's total power generation capacity was over 29,728 megawatts. Total electricity generation was 140,985.01 GWh and total electricity consumption was 116,087.51 GWh.[226] Energy production in Malaysia is largely based on oil and natural gas, owing to Malaysia's oil reserves and natural gas reserves, which is the fourth largest in Asia-Pacific region.[227]

Malaysia's road network is one of the most comprehensive in Asia and covers a total of 144,403 kilometres (89,728 mi). The main national road network is the Malaysian Federal Roads System, which span over 49,935 km (31,028 mi). Most of the federal roads in Malaysia are 2-lane roads. In town areas, federal roads may become 4-lane roads to increase traffic capacity. Nearly all federal roads are paved with tarmac except for parts of the Skudai–Pontian Highway which are paved with concrete, while parts of the Federal Highway linking Klang to Kuala Lumpur are paved with asphalt. Malaysia has over 1,798 kilometres (1,117 mi) of highways and the longest highway, the North–South Expressway, extends over 800 kilometres (497 mi) on the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia, connecting major urban centres like Kuala Lumpur, Penang and Johor Bahru. In 2015, the government announced a RM27 billion (US$8.23 billion) Pan-Borneo Highway project to upgrade all trunk roads to dual-carriageway expressways, bringing the standard of East Malaysian highways to the same level of quality as Peninsular highways.[228][229]

There are currently 1,833 kilometres (1,139 mi) of railways in Malaysia, of which 767 km (477 mi) are double tracked and electrified. Rail transport in Malaysia comprises heavy rail (KTM), light rapid transit and monorail (Rapid Rail), and a funicular railway line (Penang Hill Railway). Heavy rail is mostly used for intercity passenger and freight transport as well as some urban public transport, while LRTs are used for intra-city urban public transport. There are two commuter rail services linking Kuala Lumpur with the Kuala Lumpur International Airport. The sole monorail line in the country is used for public transport in Kuala Lumpur, while the only funicular railway line is in Penang. A rapid transit project, the KVMRT, is currently under construction to improve Kuala Lumpur's public transport system. The railway network covers most of the 11 states in Peninsular Malaysia. In East Malaysia, only the state of Sabah has railways. The network is also connected to the Thai railway 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) network in the north. If the Burma Railway is rebuilt, services to Myanmar, India, and China could be initiated. Malaysia also operated the KTM ETS, (commercially known as "ETS", short for 'Electric Train Service') an inter-city rail passenger service operated by Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad using electric multiple-unit trains. The KTM ETS is the second electric train service to be operated by the Malaysian railway company, after the KTM Komuter service. The line length is 755 km (Padang Besar – Gemas) and additional 197 km from Gemas to Johor Bahru Sentral which is under construction.

Malaysia has 118 airports, of which 38 are paved. The national airline is Malaysia Airlines, providing international and domestic air services. Major international routes and domestic routes crossing between Peninsula Malaysia and East Malaysia are served by Malaysia Airlines, AirAsia and Malindo Air while smaller domestic routes are supplemented by smaller airlines like MASwings, Firefly and Berjaya Air. Major cargo airlines include MASkargo and Transmile Air Services. Kuala Lumpur International Airport is the main and busiest airport of Malaysia. In 2014, it was the world's 13th busiest airport by international passenger traffic, recording over 25.4 million international passenger traffic. It was also the world's 20th busiest airport by passenger traffic, recording over 48.9 million passengers. Other major airports include Kota Kinabalu International Airport, which is also Malaysia's second busiest airport and busiest airport in East Malaysia with over 6.9 million passengers in 2013, and Penang International Airport, which serves Malaysia's second largest urban area, with over 5.4 million passengers in 2013.

Coronavirus pandemic

On January 12, 2021 King Al-Sultan Abdullah declared the country in a state of emergency at the request of Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin in order to slow the spread of COVID-19. Muhyiddin announced on television that parliament was suspended and elections will not be held during the emergency. The state of emergency could last until August 1, 2021. The prime minister said that a newly appointed independent committee will be able to end the state of emergency when they decide that the pandemic is over and its safe to have an election. Under the emergency rules Muhyiddin can introduce new laws without the approval of the parliament. The day before the declaration of the state of emergency Muhyddin announced a nationwide ban on travel and a 14-day lockdown in Kuala Lumpur and five states.[230]

Demographics

| Population[231][232] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 6.1 | ||

| 2000 | 23.2 | ||

| 2018 | 31.5 | ||

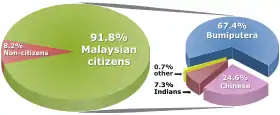

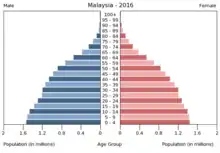

According to the Malaysian Department of Statistics, the country's population was 28,334,135 in 2010,[8] making it the 42nd most populated country. According to a 2012 estimate, the population is increasing by 1.54 percent per year. Malaysia has an average population density of 96 people per km2, ranking it 116th in the world for population density. People within the 15–64 age group constitute 69.5 percent of the total population; the 0–14 age group corresponds to 24.5 percent; while senior citizens aged 65 years or older make up 6.0 percent. In 1960, when the first official census was recorded in Malaysia, the population was 8.11 million. 91.8 per cent of the population are Malaysian citizens.[233]

Malaysian citizens are divided along local ethnic lines, with 67.4 per cent considered bumiputera.[233] The largest group of bumiputera are Malays, who are defined in the constitution as Muslims who practice Malay customs and culture. They play a dominant role politically.[234] Bumiputera status is also accorded to the non-Malay indigenous groups of Sabah and Sarawak: which includes Dayaks (Iban, Bidayuh, Orang Ulu), Kadazan-Dusun, Melanau, Bajau and others. Non-Malay bumiputeras make up more than half of Sarawak's population and over two thirds of Sabah's population.[235][236] There are also indigenous or aboriginal groups in much smaller numbers on the peninsular, where they are collectively known as the Orang Asli.[237] Laws over who gets bumiputera status vary between states.[238]

There are also two other non-Bumiputera local ethnic groups. 24.6 per cent of the population are Malaysian Chinese, while 7.3 per cent are Malaysian Indian.[233] The local Chinese have historically been more dominant in the business community. Local Indian are majority of Tamil descent.[239][240] Malaysian citizenship is not automatically granted to those born in Malaysia, but is granted to a child born of two Malaysian parents outside Malaysia. Dual citizenship is not permitted.[241] Citizenship in the states of Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysian Borneo are distinct from citizenship in Peninsular Malaysia for immigration purposes. Every citizen is issued a biometric smart chip identity card known as MyKad at the age of 12, and must carry the card at all times.[242]

The education system features a non-compulsory kindergarten education followed by six years of compulsory primary education, and five years of optional secondary education.[243] Schools in the primary education system are divided into two categories: national primary schools, which teach in Malay, and vernacular schools, which teach in Chinese or Tamil.[244] Secondary education is conducted for five years. In the final year of secondary education, students sit for the Malaysian Certificate of Education examination.[245] Since the introduction of the matriculation programme in 1999, students who completed the 12-month programme in matriculation colleges can enroll in local universities. However, in the matriculation system, only 10 per cent of places are open to non-bumiputera students.[246]

The infant mortality rate in 2009 was 6 deaths per 1000 births, and life expectancy at birth in 2009 was 75 years.[247] With the aim of developing Malaysia into a medical tourism destination, 5 per cent of the government social sector development budget is spent on health care.[248] The number of live births in Malaysia stood at 508,203 babies in the year 2016. This is a decline compared to 521,136 the previous year. There was also a decline in crude birth rate from 16.7 (2015) to 16.1 (2016) per 1,000 population. Male babies account for 51.7% of all babies born in the year 2016. The highest crude birth rate was reported at Putrajaya (30.4) and the lowest was reported at Penang (12.7). The Julau district has the highest crude birth rate nationwide at 26.9 per 1000 population, meanwhile, the lowest crude birth rate was recorded in the Selangau district. The total fertility rate in Malaysia remains below the replacement level at 1.9 babies in 2017. This is a decline of 0.1 compared to the previous year. The highest crude death rate was reported in Perlis at 7.5 per 1000 population and the lowest crude death rate was reported in Putrajaya (1.9) in 2016. Kuala Penyu was the district with the highest crude death rate while Kinabatangan recorded the lowest crude death rate in the country.[249]

The population is concentrated on Peninsular Malaysia,[250] where 20 million out of approximately 28 million Malaysians live.[44] 70 per cent of the population is urban.[150] Kuala Lumpur is the capital[150] and the largest city in Malaysia,[251] as well as its main commercial and financial centre.[252] Putrajaya, a purpose-built city constructed from 1999, is the seat of government,[253] as many executive and judicial branches of the federal government were moved there to ease growing congestion within Kuala Lumpur.[254] Due to the rise in labour-intensive industries,[255] the country is estimated to have over 3 million migrant workers; about 10 per cent of the population.[256] Sabah-based NGOs estimate that out of the 3 million that make up the population of Sabah, 2 million are illegal immigrants.[257] Malaysia hosts a population of refugees and asylum seekers numbering approximately 171,500. Of this population, approximately 79,000 are from Burma, 72,400 from the Philippines, and 17,700 from Indonesia. Malaysian officials are reported to have turned deportees directly over to human smugglers in 2007, and Malaysia employs RELA, a volunteer militia with a history of controversies, to enforce its immigration law.[258]

Religion

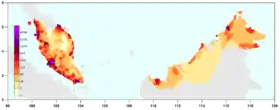

The constitution grants freedom of religion and makes Malaysia an officially secular state, while establishing Islam as the "religion of the Federation".[259] According to the Population and Housing Census 2010 figures, ethnicity and religious beliefs correlate highly. Approximately 61.3% of the population practice Islam, 19.8% practice Buddhism, 9.2% Christianity, 6.3% Hinduism and 1.3% practice Confucianism, Taoism and other traditional Chinese religions. 0.7% declared no religion and the remaining 1.4% practised other religions or did not provide any information.[8] Sunni Islam of Shafi'i school of jurisprudence is the dominant branch of Islam in Malaysia,[260][261] while 18% are nondenominational Muslims.[262]

The Malaysian constitution strictly defines what makes a "Malay", considering Malays those who are Muslim, speak Malay regularly, practise Malay customs, and lived in or have ancestors from Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore.[154] Statistics from the 2010 Census indicate that 83.6% of the Chinese population identify as Buddhist, with significant numbers of adherents following Taoism (3.4%) and Christianity (11.1%), along with small Muslim populations in areas like Penang. The majority of the Indian population follow Hinduism (86.2%), with a significant minority identifying as Christians (6.0%) or Muslims (4.1%). Christianity is the predominant religion of the non-Malay bumiputera community (46.5%) with an additional 40.4% identifying as Muslims.[8]

Muslims are obliged to follow the decisions of Syariah Courts (i.e. Shariah courts) in matters concerning their religion. The Islamic judges are expected to follow the Shafi'i legal school of Islam, which is the main madh'hab of Malaysia.[260] The jurisdiction of Syariah courts is limited to Muslims in matters such as marriage, inheritance, divorce, apostasy, religious conversion, and custody among others. No other criminal or civil offences are under the jurisdiction of the Syariah courts, which have a similar hierarchy to the Civil Courts. Despite being the supreme courts of the land, the Civil Courts do not hear matters related to Islamic practices.[263]

Languages

(click image to enlarge)

The official and national language of Malaysia is Malaysian,[150] a standardised form of the Malay language.[264] The terminology as per government policy is Bahasa Malaysia (literally "Malaysian language")[265] but legislation continues to refer to the official language as Bahasa Melayu (literally "Malay language").[266] The National Language Act 1967 specifies the Latin (Rumi) script as the official script of the national language, but does not prohibit the use of the traditional Jawi script.[267]

English remains an active second language, with its use allowed for some official purposes under the National Language Act of 1967.[267] In Sarawak, English is an official state language alongside Malaysian.[268][269][270] Historically, English was the de facto administrative language; Malay became predominant after the 1969 race riots (13 May incident).[271] Malaysian English, also known as Malaysian Standard English, is a form of English derived from British English. Malaysian English is widely used in business, along with Manglish, which is a colloquial form of English with heavy Malay, Chinese, and Tamil influences. The government discourages the use of non-standard Malay but has no power to issue compounds or fines to those who use improper Malay on their advertisements.[272][273]

Many other languages are used in Malaysia, which contains speakers of 137 living languages.[274] Peninsular Malaysia contains speakers of 41 of these languages.[275] The native tribes of East Malaysia have their own languages which are related to, but easily distinguishable from, Malay. Iban is the main tribal language in Sarawak while Dusunic and Kadazan languages are spoken by the natives in Sabah.[276] Chinese Malaysians predominantly speak Chinese dialects from the southern provinces of China. The more common Chinese varieties in the country are Cantonese, Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka, Hainanese, and Fuzhou. The Tamil language is used predominantly by a majority of Malaysian Indians along with Telugu, Malayalam. Other South Asian languages are also widely spoken in Malaysia, as well as Thai.[150] A small number of Malaysians have Caucasian ancestry and speak creole languages, such as the Portuguese-based Malaccan Creoles,[277] and the Spanish-based Chavacano language.[278]

Culture

Malaysia has a multi-ethnic, multicultural, and multilingual society. The original culture of the area stemmed from indigenous tribes that inhabited it, along with the Malays who later moved there. Substantial influence exists from Chinese and Indian culture, dating back to when foreign trade began. Other cultural influences include the Persian, Arabic, and British cultures. Due to the structure of the government, coupled with the social contract theory, there has been minimal cultural assimilation of ethnic minorities.[279]

In 1971, the government created a "National Cultural Policy", defining Malaysian culture. It stated that Malaysian culture must be based on the culture of the indigenous peoples of Malaysia, that it may incorporate suitable elements from other cultures, and that Islam must play a part in it.[280] It also promoted the Malay language above others.[281] This government intervention into culture has caused resentment among non-Malays who feel their cultural freedom was lessened. Both Chinese and Indian associations have submitted memorandums to the government, accusing it of formulating an undemocratic culture policy.[280]

Some cultural disputes exist between Malaysia and neighbouring countries, notably Indonesia. The two countries have a similar cultural heritage, sharing many traditions and items. However, disputes have arisen over things ranging from culinary dishes to Malaysia's national anthem. Strong feelings exist in Indonesia about protecting their national heritage.[282] The Malaysian government and the Indonesian government have met to defuse some of the tensions resulting from the overlaps in culture.[283] Feelings are not as strong in Malaysia, where most recognise that many cultural values are shared.[282]

Fine arts

Traditional Malaysian art was mainly centred on the areas of carving, weaving, and silversmithing.[285] Traditional art ranges from handwoven baskets from rural areas to the silverwork of the Malay courts. Common artworks included ornamental kris, beetle nut sets, and woven batik and songket fabrics. Indigenous East Malaysians are known for their wooden masks.[154] Each ethnic group have distinct performing arts, with little overlap between them. However, Malay art does show some North Indian influence due to the historical influence of India.[286]

Traditional Malay music and performing arts appear to have originated in the Kelantan-Pattani region with influences from India, China, Thailand, and Indonesia. The music is based around percussion instruments,[286] the most important of which is the gendang (drum). There are at least 14 types of traditional drums.[287] Drums and other traditional percussion instruments and are often made from natural materials.[287] Music is traditionally used for storytelling, celebrating life-cycle events, and occasions such as a harvest.[286] It was once used as a form of long-distance communication.[287] In East Malaysia, gong-based musical ensembles such as agung and kulintang are commonly used in ceremonies such as funerals and weddings.[288] These ensembles are also common in neighbouring regions such as in Mindanao in the Philippines, Kalimantan in Indonesia, and Brunei.[288]

Malaysia has a strong oral tradition that has existed since before the arrival of writing, and continues today. Each of the Malay Sultanates created their own literary tradition, influenced by pre-existing oral stories and by the stories that came with Islam.[289] The first Malay literature was in the Arabic script. The earliest known Malay writing is on the Terengganu stone, made in 1303.[154] Chinese and Indian literature became common as the numbers of speakers increased in Malaysia, and locally produced works based in languages from those areas began to be produced in the 19th century.[289] English has also become a common literary language.[154] In 1971, the government took the step of defining the literature of different languages. Literature written in Malay was called "the national literature of Malaysia", literature in other bumiputera languages was called "regional literature", while literature in other languages was called "sectional literature".[281] Malay poetry is highly developed, and uses many forms. The Hikayat form is popular, and the pantun has spread from Malay to other languages.[289]

Cuisine

Malaysia's cuisine reflects the multi-ethnic makeup of its population.[292] Many cultures from within the country and from surrounding regions have greatly influenced the cuisine. Much of the influence comes from the Malay, Chinese, Indian, Thai, Javanese, and Sumatran cultures,[154] largely due to the country being part of the ancient spice route.[293] The cuisine is very similar to that of Singapore and Brunei,[178] and also bears resemblance to Filipino cuisine.[154] The different states have varied dishes,[178] and often the food in Malaysia is different from the original dishes.[240]

Sometimes food not found in its original culture is assimilated into another; for example, Chinese restaurants in Malaysia often serve Malay dishes.[294] Food from one culture is sometimes also cooked using styles taken from another culture,[178] For example, sambal belacan (shrimp paste) are commonly used as ingredients by Chinese restaurants to create the stir fried water spinach (kangkung belacan).[295] This means that although much of Malaysian food can be traced back to a certain culture, they have their own identity.[293] Rice is popular in many dishes. Chili is commonly found in local cuisine, although this does not necessarily make them spicy.[292]

Media

Malaysia's main newspapers are owned by the government and political parties in the ruling coalition,[296][297] although some major opposition parties also have their own, which are openly sold alongside regular newspapers. A divide exists between the media in the two halves of the country. Peninsular-based media gives low priority to news from the East, and often treats the eastern states as colonies of the Peninsula.[298] As a result of this, East Malaysia region of Sarawak launched TV Sarawak as internet streaming beginning in 2014, and as TV station on 10 October 2020 to overcome the low priority and coverage of Peninsular-based media and to solidify the representation of East Malaysia. The media have been blamed for increasing tension between Indonesia and Malaysia, and giving Malaysians a bad image of Indonesians.[299] The country has Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil dailies.[298]

Freedom of the press is limited, with numerous restrictions on publishing rights and information dissemination.[300] The government has previously tried to crack down on opposition papers before elections.[297] In 2007, a government agency issued a directive to all private television and radio stations to refrain from broadcasting speeches made by opposition leaders,[301] a move condemned by politicians from the opposition Democratic Action Party.[302] Sabah, where all tabloids but one are independent of government control, has the freest press in Malaysia.[298] Laws such as the Printing Presses and Publications Act have also been cited as curtailing freedom of expression.[303]

Holidays and festivals

Malaysians observe a number of holidays and festivities throughout the year. Some are federally gazetted public holidays and some are observed by individual states. Other festivals are observed by particular ethnic or religion groups, and the main holiday of each major group has been declared a public holiday. The most observed national holiday is Hari Merdeka (Independence Day) on 31 August, commemorating the independence of the Federation of Malaya in 1957.[154] Malaysia Day on 16 September commemorates federation in 1963.[304] Other notable national holidays are Labour Day (1 May) and the King's birthday (first week of June).[154]

Muslim holidays are prominent as Islam is the state religion; Hari Raya Puasa (also called Hari Raya Aidilfitri, Malay for Eid al-Fitr), Hari Raya Haji (also called Hari Raya Aidiladha, Malay for Eid ul-Adha), Maulidur Rasul (birthday of the Prophet), and others being observed.[154] Malaysian Chinese celebrate festivals such as Chinese New Year and others relating to traditional Chinese beliefs. Wesak Day is observed and celebrated by Buddhists. Hindus in Malaysia celebrate Deepavali, the festival of lights,[305] while Thaipusam is a religious rite which sees pilgrims from all over the country converge at the Batu Caves.[306] Malaysia's Christian community celebrates most of the holidays observed by Christians elsewhere, most notably Christmas and Easter. In addition to this, the Dayak community in Sarawak celebrate a harvest festival known as Gawai,[307] and the Kadazandusun community celebrate Kaamatan.[308] Despite most festivals being identified with a particular ethnic or religious group, celebrations are universal. In a custom known as "open house" Malaysians participate in the celebrations of others, often visiting the houses of those who identify with the festival.[220]

Sports

Popular sports in Malaysia include association football, badminton, field hockey, bowls, tennis, squash, martial arts, horse riding, sailing, and skate boarding.[220] Football is the most popular sport in Malaysia and the country is currently studying the possibility of bidding as a joint host for 2034 FIFA World Cup.[309][310] Badminton matches also attract thousands of spectators, and since 1948 Malaysia has been one of four countries to hold the Thomas Cup, the world team championship trophy of men's badminton.[311] The Malaysian Lawn Bowls Federation was registered in 1997.[312] Squash was brought to the country by members of the British army, with the first competition being held in 1939.[313] The Squash Racquets Association Of Malaysia was created on 25 June 1972.[314] Malaysia has proposed a Southeast Asian football league.[315] The men's national field hockey team ranked 13th in the world as of December 2015.[316] The 3rd Hockey World Cup was hosted at Merdeka Stadium in Kuala Lumpur, as well as the 10th cup.[317] The country also has its own Formula One track–the Sepang International Circuit. It runs for 310.408 kilometres (192.88 mi), and held its first Grand Prix in 1999.[318] Traditional sports include Silat Melayu, the most common style of martial arts practised by ethnic Malays in Malaysia, Brunei, and Singapore.[319]

The Federation of Malaya Olympic Council was formed in 1953, and received recognition by the IOC in 1954. It first participated in the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games. The council was renamed the Olympic Council of Malaysia in 1964, and has participated in all but one Olympic games since its inception. The largest number of athletes ever sent to the Olympics was 57 to the 1972 Munich Olympic Games.[320] Malaysian athletes have won a total of eleven Olympic medals: eight in badminton, two in platform diving, and one in cycling.[321] The country has competed at the Commonwealth Games since 1950 as Malaya, and 1966 as Malaysia, and the games were hosted in Kuala Lumpur in 1998.[322][323]

Notes

- Section 9 of the National Language Act 1963/67 states that "The script of the national language shall be the Rumi script: provided that this shall not prohibit the use of the Malay script, more commonly known as the Jawi script, of the national language".

- Section 2 of the National Language Act 1963/67 states that "Save as provided in this Act and subject to the safeguards contained in Article 152(1) of the Constitution relating to any other language and the language of any other community in Malaysia the national language shall be used for official purposes".

- See Article 152 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia and National Language Act 1963/67.

References

- "Malaysian Flag and Coat of Arms". Malaysian Government. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "Current Population Estimates Malaysia 2016–2017". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "The States, Religion and Law of the Federation" (PDF). Constitution of Malaysia. Judicial Appointments Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

Islam is the religion of the Federation; but other religions may be practised in peace and harmony in any part of the Federation.

- "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristic Report 2010 (Updated: 05/08/2011)". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- Hariz Mohd. "Sources: Sultan of Pahang elected as new Agong". Malaysiakini. Malaysiakini. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Mackay, Derek (2005). Eastern Customs: The Customs Service in British Malaya and the Opium Trade. The Radcliffe Press. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-1-85043-844-1.

- "Demographic Statistics First Quarter 2020, Malaysia". Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. p. 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-107-50718-0.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Room, Adrian (2004). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for Over 5000 Natural Features, Countries, Capitals, Territories, Cities and Historic Sites. McFarland & Company. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7864-1814-5.

- "The World Factbook – Malaysia". Central Intelligence Agency. 2020.

- Abdul Rashid Melebek; Amat Juhari Moain (2006), Sejarah Bahasa Melayu ("History of the Malay Language"), Utusan Publications & Distributors, pp. 9–10, ISBN 978-967-61-1809-7

- Weightman, Barbara A. (2011). Dragons and Tigers: A Geography of South, East, and Southeast Asia. John Wiley and Sons. p. 449. ISBN 978-1-118-13998-1.

- Tiwary, Shanker Shiv (2009). Encyclopaedia Of Southeast Asia And Its Tribes (Set Of 3 Vols.). Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 978-81-261-3837-1.

- Singh, Kumar Suresh (2003). People of India. 26. Anthropological Survey of India. p. 981. ISBN 978-81-85938-98-1.

- Barnard, Timothy P. (2004), Contesting Malayness: Malay identity across boundaries, Singapore: Singapore University press, pp. 3–10, ISBN 978-9971-69-279-7

- Pande, Govind Chandra (2005). India's Interaction with Southeast Asia: History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 1, Part 3. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 266. ISBN 978-81-87586-24-1.

- Gopal, Lallanji (2000). The economic life of northern India: c. A.D. 700–1200. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 139. ISBN 978-81-208-0302-2.

- Ahir, D. C. (1995). A Panorama of Indian Buddhism: Selections from the Maha Bodhi journal, 1892–1992. Sri Satguru Publications. p. 612. ISBN 978-81-7030-462-3.

- Mukerjee, Radhakamal (1984). The culture and art of India. Coronet Books Inc. p. 212. ISBN 978-81-215-0114-9.

- Sarkar, Himansu Bhusan (1970). Some contributions of India to the ancient civilisation of Indonesia and Malaysia. Punthi Pustak. p. 8.

- Milner, Anthony (2010), The Malays (The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific), Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 18–19, ISBN 978-1-4443-3903-1

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (October 2001). "The Search for the 'Origins' of Melayu". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 32 (3): 315–316, 324, 327–328, 330. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000169. JSTOR 20072349.

- Mohamed Anwar Omar Din (2012). "Legitimacy of the Malays as the Sons of the Soil". Asian Social Science. Canadian Center of Science and Education: 80–81. ISSN 1911-2025.

- Reid, Anthony (2010). Imperial alchemy : nationalism and political identity in Southeast Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-87237-9.

- Bernasconi, Robert; Lott, Tommy Lee (2000). The Idea of Race. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-458-4.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (7–8 November 2003). "Collective Degradation: Slavery and the Construction of Race" (PDF). Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- d'Urville, J. S. B. C. S. D.; Ollivier, I.; De Biran, A.; Clark, G. (2003). "On the Islands of the Great Ocean". The Journal of Pacific History. 38 (2): 163. doi:10.1080/0022334032000120512. S2CID 162374626.

- Earl, George S. W. (1850). "On The Leading Characteristics of the Papuan, Australian and Malay-Polynesian Nations". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA). IV: 119.

- Barrows, David P. (1905). A History of the Philippines. American Book Company. p. 25-26.

- "Malay". Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2013.

- Suarez, Thomas (1999). Early Mapping of Southeast Asia. Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-962-593-470-9.

- "Federation of Malaya Independence Act 1957 (c. 60)e". The UK Statute Law Database. 31 July 1957. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- Spaeth, Anthony (9 December 1996). "Bound for Glory". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 17 March 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- Sakai, Minako (2009). "Reviving Malay Connections in Southeast Asia" (PDF). In Cao, Elizabeth; Morrell (eds.). Regional Minorities and Development in Asia. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-415-55130-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2014.

- Holme, Stephanie (13 February 2012). "Getaway to romance in Malaysia". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Fix, Alan G. (June 1995). "Malayan Paleosociology: Implications for Patterns of Genetic Variation among the Orang Asli". American Anthropologist. New Series. 97 (2): 313–323. doi:10.1525/aa.1995.97.2.02a00090. JSTOR 681964.

- Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T; Wurm, Stephen A (1996). Atlas of languages of intercultural communication in the Pacific, Asia and the Americas. Walter de Gruyer & Co. p. 695. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Suporno, S. (1979). "The Image of Majapahit in late Javanese and Indonesian Writing". In A. Reid; D. Marr (eds.). Perceptions of the Past. Southeast Asia publications. 4. Singapore: Heinemann Books for the Asian Studies Association of Australia. p. 180.

- "Malaysia". United States State Department. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Luscombe, Stephen. "The Map Room: South East Asia: Malaya". Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "The Encyclopædia Britannica : a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Kuar, Amarjit. "International Migration and Governance in Malaysia: Policy and Performance" (PDF). University of New England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2011.