Malta

Malta (/ˈmɒltə/,[12] /ˈmɔːltə/ (![]() listen); in Maltese: [ˈmɐltɐ]; Italian: [ˈmalta]), officially known as the Republic of Malta (Maltese: Repubblika ta' Malta) and formerly Melita, is a Southern European island country consisting of an archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea.[13] It lies 80 km (50 mi) south of Italy, 284 km (176 mi) east of Tunisia,[14] and 333 km (207 mi) north of Libya.[15] With a population of about 515,000[6] over an area of 316 km2 (122 sq mi),[5] Malta is the world's tenth smallest country in area[16][17] and fourth most densely populated sovereign country. Its capital is Valletta, which is the smallest national capital in the European Union by area at 0.8 km2 (0.31 sq mi). The official and national language is Maltese, which is descended from Sicilian Arabic that developed during the Emirate of Sicily, while English serves as the second official language. Italian and Sicilian also previously served as official and cultural languages on the island for centuries, with Italian being an official language in Malta until 1934 and a majority of the current Maltese population being at least conversational in the Italian language.

listen); in Maltese: [ˈmɐltɐ]; Italian: [ˈmalta]), officially known as the Republic of Malta (Maltese: Repubblika ta' Malta) and formerly Melita, is a Southern European island country consisting of an archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea.[13] It lies 80 km (50 mi) south of Italy, 284 km (176 mi) east of Tunisia,[14] and 333 km (207 mi) north of Libya.[15] With a population of about 515,000[6] over an area of 316 km2 (122 sq mi),[5] Malta is the world's tenth smallest country in area[16][17] and fourth most densely populated sovereign country. Its capital is Valletta, which is the smallest national capital in the European Union by area at 0.8 km2 (0.31 sq mi). The official and national language is Maltese, which is descended from Sicilian Arabic that developed during the Emirate of Sicily, while English serves as the second official language. Italian and Sicilian also previously served as official and cultural languages on the island for centuries, with Italian being an official language in Malta until 1934 and a majority of the current Maltese population being at least conversational in the Italian language.

Republic of Malta | |

|---|---|

Motto: Virtute et constantia "With strength and consistency" | |

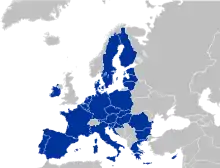

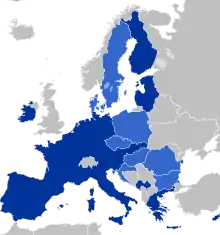

Location of Malta (green circle) – in Europe (light green & dark grey) | |

| Capital | Valletta 35°54′N 14°31′E |

| Largest town | St. Paul's Bay |

| Official languages | Maltese,[d] English |

| Other language | Italian (66% conversational)[1] |

| Ethnic groups (2019[2]) | |

| Religion (2019)[3] | 90% Christianity —83% Roman Catholic (official[4]) —7% Other Christian 5% No religion 2% Islam 3% Other religions |

| Demonym(s) | Maltese |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic |

| George Vella | |

| Robert Abela | |

| Legislature | Parliament of Malta |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 21 September 1964 | |

• Republic | 13 December 1974 |

| Area | |

• Total | 316[5] km2 (122 sq mi) (185th) |

• Water (%) | 0.001 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 514,564[6] (173rd) |

• 2011 census | 417,432[7] |

• Density | 1,633/km2 (4,229.5/sq mi) (4th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $22.802 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $48,246[8] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $15.134 billion[8] |

• Per capita | $32,021[8] |

| Gini (2019) | low · 15th |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 28th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (Central European Time) |

| UTC+2 (Central European Summer Time) | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +356 |

| ISO 3166 code | MT |

| Internet TLD | .mt[c] |

Website gov | |

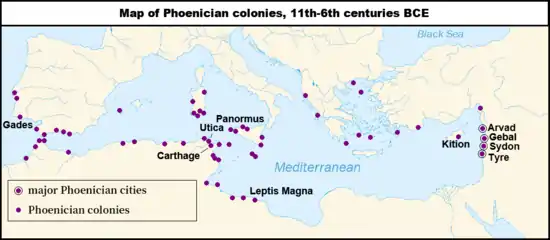

Malta has been inhabited since approximately 5900 BC.[18] Its location in the centre of the Mediterranean[19] has historically given it great strategic importance as a naval base, with a succession of powers having contested and ruled the islands, including the Phoenicians and Carthaginians, Romans, Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Aragonese, Knights of St. John, French, and British.[20] Most of these foreign influences have left some sort of mark on the country's ancient culture.

Malta became a British colony in 1813, serving as a way station for ships and the headquarters for the British Mediterranean Fleet. It was besieged by the Axis powers during World War II and was an important Allied base for operations in North Africa and the Mediterranean.[21][22] The British parliament passed the Malta Independence Act in 1964, giving Malta independence from the United Kingdom as the State of Malta, with Queen Elizabeth II as its head of state and queen.[23] The country became a republic in 1974. It has been a member state of the Commonwealth of Nations and the United Nations since independence, and joined the European Union in 2004; it became part of the eurozone monetary union in 2008.

Malta has had Christians since the time of Early Christianity, though was predominantly Muslim while under Arab rule, at which time Christians were tolerated. Muslim rule ended with the Norman invasion of Malta by Roger I in 1091. Today, Catholicism is the state religion, but the Constitution of Malta guarantees freedom of conscience and religious worship.[24][25]

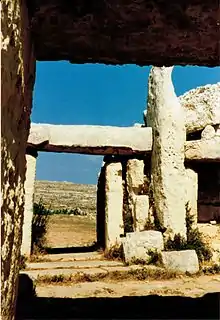

Malta is a tourist destination with its warm climate, numerous recreational areas, and architectural and historical monuments, including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Hypogeum of Ħal Saflieni,[26] Valletta,[27] and seven megalithic temples which are some of the oldest free-standing structures in the world.[28][29][30]

Etymology

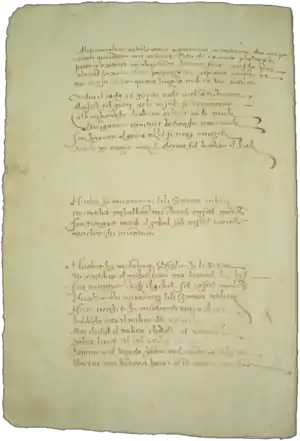

The origin of the name Malta is uncertain, and the modern-day variation is derived from the Maltese language. The most common etymology is that the word Malta is derived from the Greek word μέλι, meli, "honey".[31] The ancient Greeks called the island Μελίτη (Melitē) meaning "honey-sweet", possibly for Malta's unique production of honey; an endemic subspecies of bees live on the island.[32] The Romans called the island Melita,[33] which can be considered either a Latinisation of the Greek Μελίτη or the adaptation of the Doric Greek pronunciation of the same word Μελίτα.[34] In 1525 William Tyndale used the transliteration "Melite" in Acts 28:1 for Καὶ διασωθέντες τότε ἐπέγνωμεν ὅτι Μελίτη ἡ νῆσος καλεῖται ("And when they were escaped, then they knew that the island was called Melita")[35] as found in his translation of The New Testament that relied on Greek texts instead of Latin. "Melita" is the spelling used in the Authorized (King James) Version of 1611 and in the American Standard Version of 1901. "Malta" is widely used in more recent versions, such as The Revised Standard Version of 1946 and The New International Version of 1973.

Another conjecture suggests that the word Malta comes from the Phoenician word Maleth, "a haven",[36] or 'port'[37] in reference to Malta's many bays and coves. Few other etymological mentions appear in classical literature, with the term Malta appearing in its present form in the Antonine Itinerary (Itin. Marit. p. 518; Sil. Ital. xiv. 251).[38]

History

Malta has been inhabited from around 5900 BC,[39] since the arrival of settlers from the island of Sicily.[40] A significant prehistoric Neolithic culture marked by Megalithic structures, which date back to c. 3600 BC, existed on the islands, as evidenced by the temples of Bugibba, Mnajdra, Ggantija and others. The Phoenicians colonised Malta between 800–700 BC, bringing their Semitic language and culture.[41] They used the islands as an outpost from which they expanded sea explorations and trade in the Mediterranean until their successors, the Carthaginians, were ousted by the Romans in 216 BC with the help of the Maltese inhabitants, under whom Malta became a municipium.[42]

After a probable sack by the Vandals,[43] Malta fell under Byzantine rule (4th to 9th century) and the islands were then invaded by the Aghlabids in AD 870. The fate of the population after the Arab invasion is unclear but it seems the islands may have been repopulated at the beginning of the second millennium by settlers from Arab-ruled Sicily who spoke Siculo-Arabic.[44]

The Muslim rule was ended by the Normans who conquered the island in 1091. The islands were completely re-Christianised by 1249.[45] The islands were part of the Kingdom of Sicily until 1530 and were briefly controlled by the Capetian House of Anjou. In 1530 Charles V of Spain gave the Maltese islands to the Order of Knights of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem in perpetual lease.

The French under Napoleon took hold of the Maltese islands in 1798, although with the aid of the British the Maltese were able to oust French control two years later. The inhabitants subsequently asked Britain to assume sovereignty over the islands under the conditions laid out in a Declaration of Rights,[46] stating that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control." As part of the Treaty of Paris in 1814, Malta became a British colony. It ultimately rejected an attempted integration with the United Kingdom in 1956 after the British proved reluctant to integrate.

Malta became independent on 21 September 1964 (Independence Day). Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta, with a Governor-General exercising authority on her behalf. On 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) it became a republic within the Commonwealth, with the President as head of state. On 31 March 1979, Malta saw the withdrawal of the last British troops and the Royal Navy from Malta. This day is known as Freedom Day and Malta declared itself as a neutral and non-aligned state. Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004 and joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2008.[47]

Prehistory

Pottery found by archaeologists at the Skorba Temples resembles that found in Italy, and suggests that the Maltese islands were first settled in 5200 BC mainly by Stone Age hunters or farmers who had arrived from the Italian island of Sicily, possibly the Sicani. The extinction of the dwarf hippos , giant swans and dwarf elephants has been linked to the earliest arrival of humans on Malta.[48] Prehistoric farming settlements dating to the Early Neolithic period were discovered in open areas and also in caves, such as Għar Dalam.[49]

The Sicani were the only tribe known to have inhabited the island at this time[40][50] and are generally regarded as being closely related to the Iberians.[51] The population on Malta grew cereals, raised livestock and, in common with other ancient Mediterranean cultures, worshiped a fertility figure represented in Maltese prehistoric artifacts exhibiting the proportions seen in similar statuettes, including the Venus of Willendorf.

Pottery from the Għar Dalam phase is similar to pottery found in Agrigento, Sicily. A culture of megalithic temple builders then either supplanted or arose from this early period. Around the time of 3500 BC, these people built some of the oldest existing free-standing structures in the world in the form of the megalithic Ġgantija temples on Gozo;[52] other early temples include those at Ħaġar Qim and Mnajdra.[30][53][54]

The temples have distinctive architecture, typically a complex trefoil design, and were used from 4000 to 2500 BC. Animal bones and a knife found behind a removable altar stone suggest that temple rituals included animal sacrifice. Tentative information suggests that the sacrifices were made to the goddess of fertility, whose statue is now in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta.[55] The culture apparently disappeared from the Maltese Islands around 2500 BC. Archaeologists speculate that the temple builders fell victim to famine or disease, but this is not certain.

Another archaeological feature of the Maltese Islands often attributed to these ancient builders is equidistant uniform grooves dubbed "cart tracks" or "cart ruts" which can be found in several locations throughout the islands, with the most prominent being those found in Misraħ Għar il-Kbir, which is informally known as "Clapham Junction". These may have been caused by wooden-wheeled carts eroding soft limestone.[56][57]

After 2500 BC, the Maltese Islands were depopulated for several decades until the arrival of a new influx of Bronze Age immigrants, a culture that cremated its dead and introduced smaller megalithic structures called dolmens to Malta.[58] In most cases, there are small chambers here, with the cover made of a large slab placed on upright stones. They are claimed to belong to a population certainly different from that which built the previous megalithic temples. It is presumed the population arrived from Sicily because of the similarity of Maltese dolmens to some small constructions found on the largest island of the Mediterranean sea.[59]

Greeks, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Romans

Phoenician traders[60] colonised the islands sometime after 1000 BC[14] as a stop on their trade routes from the eastern Mediterranean to Cornwall, joining the natives on the island.[61] The Phoenicians inhabited the area now known as Mdina, and its surrounding town of Rabat, which they called Maleth.[62][63] The Romans, who also much later inhabited Mdina, referred to it (and the island) as Melita.[32]

After the fall of Phoenicia in 332 BC, the area came under the control of Carthage, a former Phoenician colony.[14][64] During this time the people on Malta mainly cultivated olives and carob and produced textiles.[64]

During the First Punic War, the island was conquered after harsh fighting by Marcus Atilius Regulus.[65] After the failure of his expedition, the island fell back in the hands of Carthage, only to be conquered again in 218 BC, during the Second Punic War, by Roman Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus.[65] After that, Malta became Foederata Civitas, a designation that meant it was exempt from paying tribute or the rule of Roman law, and fell within the jurisdiction of the province of Sicily.[32] Punic influence, however, remained vibrant on the islands with the famous Cippi of Melqart, pivotal in deciphering the Punic language, dedicated in the 2nd century BC.[66][67] Also the local Roman coinage, which ceased in the 1st century BC,[68] indicates the slow pace of the island's Romanization, since the last locally minted coins still bear inscriptions in Ancient Greek on the obverse (like "ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΩ", meaning "of the Maltese") and Punic motifs, showing the resistance of the Greek and Punic cultures.[69]

The Greeks settled in the Maltese islands beginning circa 700 BC, as testified by several architectural remains, and remained throughout the Roman dominium.[70] They called the island Melite (Ancient Greek: Μελίτη).[71][72] At around 160 BC coins struck in Malta bore the Greek ‘ΜΕΛΙΤΑΙΩΝ’ (Melitaion) meaning ‘of the Maltese’. By 50 BC Maltese coins had a Greek legend on one side and a Latin one on the other. Later coins were issued with just the Latin legend ‘MELITAS’. The depiction of aspects of the Punic religion, together with the use of the Greek alphabet, testifies to the resilience of Punic and Greek culture in Malta long after the arrival of the Romans.[73]

In the 1st century BC, Roman Senator and orator Cicero commented on the importance of the Temple of Juno, and on the extravagant behaviour of the Roman governor of Sicily, Verres.[74] During the 1st century BC the island was mentioned by Pliny the Elder and Diodorus Siculus: the latter praised its harbours, the wealth of its inhabitants, its lavishly decorated houses and the quality of its textile products. In the 2nd century, Emperor Hadrian (r. 117–38) upgraded the status of Malta to municipium or free town: the island local affairs were administered by four quattuorviri iuri dicundo and a municipal senate, while a Roman procurator, living in Mdina, represented the proconsul of Sicily.[65] In 58 AD, Paul the Apostle was washed up on the islands together with Luke the Evangelist after their ship was wrecked on the islands.[65] Paul the Apostle remained on the islands three months, preaching the Christian faith.[65] The island is mentioned at the Acts of the Apostles as Melitene (Greek: Μελιτήνη).[75]

In 395, when the Roman Empire was divided for the last time at the death of Theodosius I, Malta, following Sicily, fell under the control of the Western Roman Empire.[76] During the Migration Period as the Western Roman Empire declined, Malta came under attack and was conquered or occupied a number of times.[68] From 454 to 464 the islands were subdued by the Vandals, and after 464 by the Ostrogoths.[65] In 533 Belisarius, on his way to conquer the Vandal Kingdom in North Africa, reunited the islands under Imperial (Eastern) rule.[65] Little is known about the Byzantine rule in Malta: the island depended on the theme of Sicily and had Greek Governors and a small Greek garrison.[65] While the bulk of population continued to be constituted by the old, Latinized dwellers, during this period its religious allegiance oscillated between the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople.[65] The Byzantine rule introduced Greek families to the Maltese collective.[77] Malta remained under the Byzantine Empire until 870, when it fell to the Arabs.[65][78]

Arab period and the Middle Ages

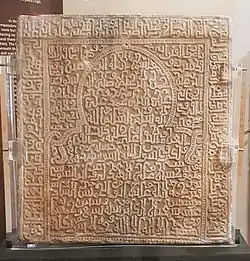

Malta became involved in the Arab–Byzantine wars, and the conquest of Malta is closely linked with that of Sicily that began in 827 after Admiral Euphemius' betrayal of his fellow Byzantines, requesting that the Aghlabids invade the island.[79] The Muslim chronicler and geographer al-Himyari recounts that in 870, following a violent struggle against the defending Byzantines, the Arab invaders, first led by Halaf al-Hadim, and later by Sawada ibn Muhammad,[80] looted and pillaged the island, destroying the most important buildings, and leaving it practically uninhabited until it was recolonised by the Arabs from Sicily in 1048–1049.[80] It is uncertain whether this new settlement took place as a consequence of demographic expansion in Sicily, as a result of a higher standard of living in Sicily (in which case the recolonisation may have taken place a few decades earlier), or as a result of civil war which broke out among the Arab rulers of Sicily in 1038.[81] The Arab Agricultural Revolution introduced new irrigation, some fruits and cotton, and the Siculo-Arabic language was adopted on the island from Sicily; it would eventually evolve into the Maltese language.[82]

The Christians on the island were allowed to practice their religion if they paid jizya, a tax for non-Muslims for exemption from military service, but non-Muslims were exempt from the tax that Muslims had to pay (zakat).[83]

Norman conquest

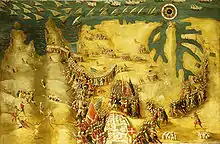

.jpg.webp)

The Normans attacked Malta in 1091, as part of their conquest of Sicily.[84] The Norman leader, Roger I of Sicily, was welcomed by Christian captives.[32] The notion that Count Roger I reportedly tore off a portion of his checkered red-and-white banner and presented it to the Maltese in gratitude for having fought on his behalf, forming the basis of the modern flag of Malta, is founded in myth.[32][85]

Malta became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Sicily, which also covered the island of Sicily and the southern half of the Italian Peninsula.[32] The Catholic Church was reinstated as the state religion, with Malta under the See of Palermo, and some Norman architecture sprang up around Malta, especially in its ancient capital Mdina.[32] Tancred, King of Sicily, the second to last Norman monarch, made Malta a fief of the kingdom and installed a Count of Malta in 1192. As the islands were much desired due to their strategic importance, it was during this time that the men of Malta were militarised to fend off attempted conquest; early Counts were skilled Genoese privateers.[32]

The kingdom passed on to the dynasty of Hohenstaufen from 1194 until 1266. During this period, when Frederick II of Hohenstaufen began to reorganise his Sicilian kingdom, Western culture and religion began to exert their influence more intensely.[86] Malta was declared a county and a marquisate, but its trade was totally ruined. For a long time it remained solely a fortified garrison.[87]

A mass expulsion of Arabs occurred in 1224, and the entire Christian male population of Celano in Abruzzo was deported to Malta in the same year.[32] In 1249 Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, decreed that all remaining Muslims be expelled from Malta[88] or compelled to convert.[89][90]

For a brief period, the kingdom passed to the Capetian House of Anjou,[91] but high taxes made the dynasty unpopular in Malta, due in part to Charles of Anjou's war against the Republic of Genoa, and the island of Gozo was sacked in 1275.[32]

Crown of Aragon rule and the Knights of Malta

Malta was ruled by the House of Barcelona, the ruling dynasty of the Crown of Aragon, from 1282 to 1409,[92] with the Aragonese aiding the Maltese insurgents in the Sicilian Vespers in a naval battle in Grand Harbour in 1283.[93]

Relatives of the Kings of Aragon ruled the island until 1409 when it formally passed to the Crown of Aragon. Early on in the Aragonese ascendancy, the sons of the monarchs received the title Count of Malta. During this time much of the local nobility was created. By 1397, however, the bearing of the comital title reverted to a feudal basis, with two families fighting over the distinction, which caused some conflict. This led King Martin I of Sicily to abolish the title. The dispute over the title returned when the title was reinstated a few years later and the Maltese, led by the local nobility, rose up against Count Gonsalvo Monroy.[32] Although they opposed the Count, the Maltese voiced their loyalty to the Sicilian Crown, which so impressed King Alfonso that he did not punish the people for their rebellion. Instead, he promised never to grant the title to a third party and incorporated it back into the crown. The city of Mdina was given the title of Città Notabile as a result of this sequence of events.[32]

On 23 March 1530,[94] Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, gave the islands to the Knights Hospitaller under the leadership of Frenchman Philippe Villiers de L'Isle-Adam, Grand Master of the Order,[95][96] in perpetual lease for which they had to pay an annual tribute of one single Maltese Falcon.[97][98][99][100][101][102][103] These knights, a military religious order also known as the Order of St John and later as the Knights of Malta, had been driven out of Rhodes by the Ottoman Empire in 1522.[104]

The Knights Hospitaller were the rulers of Malta and Gozo between 1530 and 1798.[105] During this period, the strategic and military importance of the island grew greatly as the small yet efficient fleet of the Order of Saint John launched their attacks from this new base targeting the shipping lanes of the Ottoman territories around the Mediterranean Sea.[105][106]

In 1551, the population of the island of Gozo (around 5,000 people) were enslaved by Barbary pirates and taken to the Barbary Coast in North Africa.[107]

The knights, led by Frenchman Jean Parisot de Valette, Grand Master of the Order, withstood the Great Siege of Malta by the Ottomans in 1565.[96] The knights, with the help of Spanish and Maltese forces, were victorious and repelled the attack. Speaking of the battle Voltaire said, "Nothing is better known than the siege of Malta."[108][109] After the siege they decided to increase Malta's fortifications, particularly in the inner-harbour area, where the new city of Valletta, named in honour of Valette, was built. They also established watchtowers along the coasts – the Wignacourt, Lascaris and De Redin towers – named after the Grand Masters who ordered the work. The Knights' presence on the island saw the completion of many architectural and cultural projects, including the embellishment of Città Vittoriosa (modern Birgu), the construction of new cities including Città Rohan (modern Ħaż-Żebbuġ) . Ħaż-Żebbuġ is one of the oldest cities of Malta, it also has one of the largest squares of Malta.

French period and British conquest

The Knights' reign ended when Napoleon captured Malta on his way to Egypt during the French Revolutionary Wars in 1798. Over the years preceding Napoleon's capture of the islands, the power of the Knights had declined and the Order had become unpopular. Napoleon's fleet arrived in 1798, en route to his expedition of Egypt. As a ruse towards the Knights, Napoleon asked for a safe harbour to resupply his ships, and then turned his guns against his hosts once safely inside Valletta. Grand Master Hompesch capitulated, and Napoleon entered Malta.[110]

During 12–18 June 1798, Napoleon resided at the Palazzo Parisio in Valletta.[111][112][113] He reformed national administration with the creation of a Government Commission, twelve municipalities, a public finance administration, the abolition of all feudal rights and privileges, the abolition of slavery and the granting of freedom to all Turkish and Jewish slaves.[114][115] On the judicial level, a family code was framed and twelve judges were nominated. Public education was organised along principles laid down by Bonaparte himself, providing for primary and secondary education.[115][116] He then sailed for Egypt leaving a substantial garrison in Malta.[117]

The French forces left behind became unpopular with the Maltese, due particularly to the French forces' hostility towards Catholicism and pillaging of local churches to fund Napoleon's war efforts. French financial and religious policies so angered the Maltese that they rebelled, forcing the French to depart. Great Britain, along with the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily, sent ammunition and aid to the Maltese and Britain also sent her navy, which blockaded the islands.[115]

On 28 October 1798, Captain Sir Alexander Ball successfully completed negotiations with the French garrison on Gozo, the 217 French soldiers there agreeing to surrender without a fight and transferring the island to the British. The British transferred the island to the locals that day, and it was administered by Archpriest Saverio Cassar on behalf of Ferdinand III of Sicily. Gozo remained independent until Cassar was removed from power by the British in 1801.[118]

General Claude-Henri Belgrand de Vaubois surrendered his French forces in 1800.[115] Maltese leaders presented the main island to Sir Alexander Ball, asking that the island become a British Dominion. The Maltese people created a Declaration of Rights in which they agreed to come "under the protection and sovereignty of the King of the free people, His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland". The Declaration also stated that "his Majesty has no right to cede these Islands to any power...if he chooses to withdraw his protection, and abandon his sovereignty, the right of electing another sovereign, or of the governing of these Islands, belongs to us, the inhabitants and aborigines alone, and without control."[115][46]

British Empire and the Second World War

In 1814, as part of the Treaty of Paris,[115][119] Malta officially became a part of the British Empire and was used as a shipping way-station and fleet headquarters. After the Suez Canal opened in 1869, Malta's position halfway between the Strait of Gibraltar and Egypt proved to be its main asset, and it was considered an important stop on the way to India, a central trade route for the British.

A Turkish Military Cemetery was commissioned by Sultan Abdul Aziz and built between 1873-1874 for the fallen Ottoman soldiers of the Great Siege of Malta.

Between 1915 and 1918, during the First World War, Malta became known as the Nurse of the Mediterranean due to the large number of wounded soldiers who were accommodated in Malta.[120] In 1919 British troops fired into a crowd protesting against new taxes, killing four. The event, known as Sette Giugno (Italian for 7 June), is commemorated every year and is one of five National Days.[121][122]

Before the Second World War, Valletta was the location of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean Fleet's headquarters; however, despite Winston Churchill's objections,[123] the command was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, in April 1937 out of fear that it was too susceptible to air attacks from Europe.[123][124][125]

During the Second World War, Malta played an important role for the Allies; being a British colony, situated close to Sicily and the Axis shipping lanes, Malta was bombarded by the Italian and German air forces. Malta was used by the British to launch attacks on the Italian navy and had a submarine base. It was also used as a listening post, intercepting German radio messages including Enigma traffic.[126] The bravery of the Maltese people during the second Siege of Malta moved King George VI to award the George Cross to Malta on a collective basis on 15 April 1942 "to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history". Some historians argue that the award caused Britain to incur disproportionate losses in defending Malta, as British credibility would have suffered if Malta had surrendered, as British forces in Singapore had done.[127] A depiction of the George Cross now appears in the upper hoist corner of the Flag of Malta and on the country's arms. The collective award remained unique until April 1999, when the Royal Ulster Constabulary became the second – and, to date, the only other – recipient of a collective George Cross.[128]

Independence and Republic

.jpg.webp)

Malta achieved its independence as the State of Malta on 21 September 1964 (Independence Day) after intense negotiations with the United Kingdom, led by Maltese Prime Minister George Borġ Olivier. Under its 1964 constitution, Malta initially retained Queen Elizabeth II as Queen of Malta and thus head of state, with a governor-general exercising executive authority on her behalf. In 1971, the Malta Labour Party led by Dom Mintoff won the general elections, resulting in Malta declaring itself a republic on 13 December 1974 (Republic Day) within the Commonwealth, with the President as head of state. A defence agreement was signed soon after independence, and after being re-negotiated in 1972, expired on 31 March 1979.[129] Upon its expiry, the British base closed down and all lands formerly controlled by the British on the island were given up to the Maltese government.[130]

Malta adopted a policy of neutrality in 1980.[131] In 1989, Malta was the venue of a summit between US President George H.W. Bush and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, their first face-to-face encounter, which signalled the end of the Cold War.[132]

On 16 July 1990, Malta, through its foreign minister, Guido de Marco, applied to join the European Union.[133] After tough negotiations, a referendum was held on 8 March 2003, which resulted in a favourable vote.[134] General Elections held on 12 April 2003, gave a clear mandate to the Prime Minister, Eddie Fenech Adami, to sign the treaty of accession to the European Union on 16 April 2003 in Athens, Greece.[135]

Malta joined the European Union on 1 May 2004.[136] Following the European Council of 21–22 June 2007, Malta joined the eurozone on 1 January 2008.[137]

Politics

Malta is a republic[24] whose parliamentary system and public administration are closely modelled on the Westminster system. Malta had the second-highest voter turnout in the world (and the highest for nations without mandatory voting), based on election turnout in national lower house elections from 1960 to 1995.[138] The unicameral Parliament is made up of the President of Malta and the House of Representatives (Maltese: Kamra tad-Deputati). The President of Malta, a largely ceremonial position, is appointed for a five-year term by a resolution of the House of Representatives carried by a simple majority. Members of the House of Representatives are elected by direct universal suffrage through single transferable vote every five years, unless the House is dissolved earlier by the president either on the advice of the prime minister or through the adoption of a motion of no confidence carried within the House of Representatives and not overturned within three days. In either of these cases, the president may alternatively choose to invite another Member of Parliament who invariably should command the majority of the House of Representatives to form an alternative government for the remainder of the legislature.

The House of Representatives is nominally made up of 65 members of parliament whereby 5 members of parliament are elected from each of the thirteen electoral districts. However, where a party wins an absolute majority of votes but does not have a majority of seats, that party is given additional seats to ensure a parliamentary majority. The 80th article of the Constitution of Malta provides that the president appoint as prime minister "... the member of the House of Representatives who, in his judgment, is best able to command the support of a majority of the members of that House".[24]

Maltese politics is a two-party system dominated by the Labour Party (Maltese: Partit Laburista), a centre-left social democratic party, and the Nationalist Party (Maltese: Partit Nazzjonalista), a centre-right Christian democratic party. The Labour Party has been the governing party since 2013 and is currently led by Prime Minister Robert Abela, who has been in office since 13 January 2020. The Nationalist Party, with Bernard Grech as its leader, is currently in opposition. Two parliamentary seats are held by independent politicians who were formerly with the Democratic Party (Maltese: Partit Demokratiku), a centre-left social liberal party which had contested under the Nationalist-led Forza Nazzjonali electoral alliance in 2017. There are a number of small political parties in Malta which have no parliamentary representation.

Until the Second World War, Maltese politics was dominated by the Language Question fought out by Italophone and Anglophone parties.[139] Post-war politics dealt with constitutional questions on the relations with Britain (first with integration then independence) and, eventually, relations with the European Union.

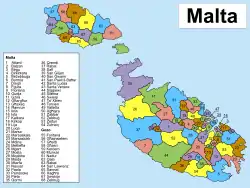

Administrative divisions

Malta has had a system of local government since 1993,[140] based on the European Charter of Local Self-Government. The country is divided into five regions (one of them being Gozo), with each region having its own Regional Committee, serving as the intermediate level between local government and national government.[141] The regions are divided into local councils, of which there are currently 68 (54 in Malta and 14 in Gozo). The six districts (five on Malta and the sixth being Gozo) serve primarily statistical purposes.[142]

Each council is made up of a number of councillors (from 5 to 13, depending on and relative to the population they represent). A mayor and a deputy mayor are elected by and from the councillors. The executive secretary, who is appointed by the council, is the executive, administrative and financial head of the council. Councillors are elected every four years through the single transferable vote. People who are eligible to vote in the election of the Maltese House of Representatives as well as a resident citizens of the EU are eligible to vote. Due to system reforms, no elections were held before 2012. Since then, elections have been held every two years for an alternating half of the councils.

Local councils are responsible for the general upkeep and embellishment of the locality (including repairs to non-arterial roads), allocation of local wardens, and refuse collection; they also carry out general administrative duties for the central government such as the collection of government rents and funds and answer government-related public inquiries. Additionally, a number of individual towns and villages in the Republic of Malta have sister cities.

Military

The objectives of the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM) are to maintain a military organisation with the primary aim of defending the islands' integrity according to the defence roles as set by the government in an efficient and cost-effective manner. This is achieved by emphasising the maintenance of Malta's territorial waters and airspace integrity.[143]

The AFM also engages in combating terrorism, fighting against illicit drug trafficking, conducting anti-illegal immigrant operations and patrols, and anti-illegal fishing operations, operating search and rescue (SAR) services, and physical or electronic security and surveillance of sensitive locations. Malta's search-and-rescue area extends from east of Tunisia to west of Crete, covering an area of around 250,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi).[144]

As a military organisation, the AFM provides backup support to the Malta Police Force (MPF) and other government departments/agencies in situations as required in an organised, disciplined manner in the event of national emergencies (such as natural disasters) or internal security and bomb disposal.[145]

In 2020, Malta signed and ratified the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[146][147]

Geography

Malta is an archipelago in the central Mediterranean (in its eastern basin), some 80 km (50 mi) from southern Italy across the Malta Channel. Only the three largest islands – Malta (Malta), Gozo (Għawdex) and Comino (Kemmuna) – are inhabited. The islands of the archipelago lie on the Malta plateau, a shallow shelf formed from the high points of a land bridge between Sicily and North Africa that became isolated as sea levels rose after the last Ice Age.[148] The archipelago is located on the African tectonic plate.[149][150] Malta was considered an island of North Africa for centuries.[151]

Numerous bays along the indented coastline of the islands provide good harbours. The landscape consists of low hills with terraced fields. The highest point in Malta is Ta' Dmejrek, at 253 m (830 ft), near Dingli. Although there are some small rivers at times of high rainfall, there are no permanent rivers or lakes on Malta. However, some watercourses have fresh water running all year round at Baħrija near Ras ir-Raħeb, at l-Imtaħleb and San Martin, and at Lunzjata Valley in Gozo.

Phytogeographically, Malta belongs to the Liguro-Tyrrhenian province of the Mediterranean Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Malta belongs to the terrestrial ecoregion of Tyrrhenian-Adriatic sclerophyllous and mixed forests[152]

_01_ies.jpg.webp)

The minor islands that form part of the archipelago are uninhabited and include:

- Barbaġanni Rock (Gozo)

- Cominotto, (Kemmunett)

- Dellimara Island (Marsaxlokk)

- Filfla (Żurrieq)/(Siġġiewi)

- Fessej Rock

- Fungus Rock, (Il-Ġebla tal-Ġeneral) (Gozo)

- Għallis Rock (Naxxar)

- Ħalfa Rock (Gozo)

- Large Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- Islands of St. Paul/Selmunett Island (Mellieħa)

- Manoel Island, which connects to the town of Gżira, on the mainland, via a bridge

- Mistra Rocks (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Taċ-Ċawl Rock (Gozo)

- Qawra Point/Ta' Fraben Island (San Pawl il-Baħar)

- Small Blue Lagoon Rocks (Comino)

- Sala Rock (Żabbar)

- Xrobb l-Għaġin Rock (Marsaxlokk)

- Ta' taħt il-Mazz Rock

Climate

Malta has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa),[25][153] with mild winters and hot summers, hotter in the inland areas. Rain occurs mainly in autumn and winter, with summer being generally dry.

The average yearly temperature is around 23 °C (73 °F) during the day and 15.5 °C (59.9 °F) at night. In the coldest month – January – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 12 to 18 °C (54 to 64 °F) during the day and minimum 6 to 12 °C (43 to 54 °F) at night. In the warmest month – August – the typical maximum temperature ranges from 28 to 34 °C (82 to 93 °F) during the day and minimum 20 to 24 °C (68 to 75 °F) at night. Amongst all capitals in the continent of Europe, Valletta – the capital of Malta has the warmest winters, with average temperatures of around 15 to 16 °C (59 to 61 °F) during the day and 9 to 10 °C (48 to 50 °F) at night in the period January–February. In March and December average temperatures are around 17 °C (63 °F) during the day and 11 °C (52 °F) at night.[154] Large fluctuations in temperature are rare. Snow is very rare on the island, although various snowfalls have been recorded in the last century, the last one reported in various locations across Malta in 2014.[155]

The average annual sea temperature is 20 °C (68 °F), from 15–16 °C (59–61 °F) in February to 26 °C (79 °F) in August. In the 6 months – from June to November – the average sea temperature exceeds 20 °C (68 °F).[156][157][158]

The annual average relative humidity is high, averaging 75%, ranging from 65% in July (morning: 78% evening: 53%) to 80% in December (morning: 83% evening: 73%).[159]

Sunshine duration hours total around 3,000 per year, from an average 5.2 hours of sunshine duration per day in December to an average above 12 hours in July.[157][160] This is about double that of cities in the northern half of Europe, for comparison: London – 1,461;[161] however, in winter it has up to four times more sunshine; for comparison: in December, London has 37 hours of sunshine[161] whereas Malta has above 160.

| Climate data for Malta (Luqa in the south-east part of main island, 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.5 (83.3) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.8 (55.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 98.5 (3.88) |

60.1 (2.37) |

44.2 (1.74) |

20.7 (0.81) |

16.0 (0.63) |

4.6 (0.18) |

0.3 (0.01) |

12.8 (0.50) |

58.6 (2.31) |

82.9 (3.26) |

92.3 (3.63) |

109.2 (4.30) |

595.8 (23.46) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 58 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.3 | 178.1 | 227.2 | 253.8 | 309.7 | 336.9 | 376.7 | 352.2 | 270.0 | 223.8 | 195.0 | 161.2 | 3,054 |

| Source: Meteo Climate (1981–2010 Data),[162] MaltaWeather.com (Sun data)[163] | |||||||||||||

Urbanisation

According to Eurostat, Malta is composed of two larger urban zones nominally referred to as "Valletta" (the main island of Malta) and "Gozo". The main urban area covers the entire main island, with a population of around 400,000.[164][165] The core of the urban area, the greater city of Valletta, has a population of 205,768.[166] According to Demographia, the Valletta urban area has a population of 300,000.[167] According to European Spatial Planning Observation Network, Malta is identified as functional urban area (FUA) with the population of 355,000.[168] According to the United Nations, about 95 per cent of the area of Malta is urban and the number grows every year.[169] Also, according to the results of ESPON and EU Commission studies, "the whole territory of Malta constitutes a single urban region".[170]

Occasionally in books,[171] government publications and documents,[172][173][174] and in some international institutions,[175] Malta is referred to as a city-state. Sometimes Malta is listed in rankings concerning cities[176] or metropolitan areas.[177] Also, the Maltese coat-of-arms bears a mural crown described as "representing the fortifications of Malta and denoting a City State".[178] Malta, with area of 316 km2 (122 sq mi) and population of 0.4 million, is one of the most densely populated countries worldwide.

Flora

The Maltese islands are home to a wide diversity of indigenous, sub-endemic and endemic plants.[179] They feature many traits typical of a Mediterranean climate, such as drought resistance. The most common indigenous trees on the islands are olive (Olea europaea), carob (Ceratonia siliqua), fig (ficus carica), holm oak (Quericus ilex) and Aleppo pine (Pinus halpensis), while the most common non-native trees are eucalyptus, acacia and opuntia. Endemic plants include the national flower widnet il-baħar (Cheirolophus crassifolius), sempreviva ta' Malta (Helichrysum melitense), żigland t' Għawdex (Hyoseris frutescens) and ġiżi ta' Malta (Matthiola incana subsp. melitensis) while sub-endemics include kromb il-baħar (Jacobaea maritima subsp. sicula) and xkattapietra (Micromeria microphylla).[180] The flora and biodiversity of Malta is severely endangered by habitat loss, invasive species and human intervention.[181]

Economy

General

Malta is classified as an advanced economy together with 32 other countries according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[182] Until 1800, Malta depended on cotton, tobacco and its shipyards for exports. Once under British control, they came to depend on Malta Dockyard for support of the Royal Navy, especially during the Crimean War of 1854. The military base benefited craftsmen and all those who served the military.[183]

In 1869, the opening of the Suez Canal gave Malta's economy a great boost, as there was a massive increase in the shipping which entered the port. Ships stopping at Malta's docks for refuelling helped the Entrepôt trade, which brought additional benefits to the island. However, towards the end of the 19th century, the economy began declining, and by the 1940s Malta's economy was in serious crisis. One factor was the longer range of newer merchant ships that required fewer refuelling stops.[184]

Currently, Malta's major resources are limestone, a favourable geographic location and a productive labour force. Malta produces only about 20 percent of its food needs, has limited fresh water supplies because of the drought in the summer, and has no domestic energy sources, aside from the potential for solar energy from its plentiful sunlight. The economy is dependent on foreign trade (serving as a freight trans-shipment point), manufacturing (especially electronics and textiles), and tourism.[185]

Access to biocapacity in Malta is below the world average. In 2016, Malta had 0.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person within its territory, contrasted with a global average of 1.6 hectares per person.[186][187] Additionally, residents of Malta exhibited an ecological footprint of consumption of 5.8 global hectares of biocapacity per person, resulting in a sizable biocapacity deficit.[186]

Film production has contributed to the Maltese economy.[188] The film Sons of the Sea was the first shot in Malta, in 1925;[189] by 2016, over 100 feature films had been entirely or partially filmed in the country since. Malta has served as a "double" for a wide variety of locations and historic periods including Ancient Greece, Ancient and modern Rome, Iraq, the Middle East and many more.[190] The Maltese government introduced financial incentives for filmmakers in 2005.[191] The current financial incentives to foreign productions as of 2015 stand at 25 per cent with an additional 2 per cent if Malta stands in as Malta; meaning a production can get up to 27 per cent back on their eligible spending incurred in Malta.[192]

In preparation for Malta's membership in the European Union, which it joined on 1 May 2004, it privatised some state-controlled firms and liberalised markets. For example, the government announced on 8 January 2007 that it was selling its 40 per cent stake in MaltaPost, to complete a privatisation process which had been ongoing for the previous five years.[193] From 2000 to 2010, Malta privatised telecommunications,[194] postal services, shipyards[195] and Malta International Airport.[196]

Malta has a financial regulator, the Malta Financial Services Authority (MFSA), with a strong business development mindset, and the country has been successful in attracting gaming businesses, aircraft and ship registration, credit-card issuing banking licences and also fund administration. Service providers to these industries, including fiduciary and trustee business, are a core part of the growth strategy of the island. Malta has made strong headway in implementing EU Financial Services Directives including UCITs IV and soon AIFMD. As a base for alternative asset managers who must comply with new directives, Malta has attracted a number of key players including IDS, Iconic Funds, Apex Fund Services and TMF/Customs House.[197]

Malta and Tunisia in 2006 discussed the commercial exploitation of the continental shelf between their countries, particularly for petroleum exploration.[198] These discussions are also undergoing between Malta and Libya for similar arrangements.[199]

As of 2015, Malta did not have a property tax. Its property market, especially around the harbour area, was booming, with the prices of apartments in some towns like St Julian's, Sliema and Gzira skyrocketing.[200]

According to Eurostat data, Maltese GDP per capita stood at 88 per cent of the EU average in 2015 with €21,000.[201]

The National Development and Social Fund from the Individual Investor Programme, a citizenship by investment programme also known as the "citizenship scheme", has become a significant income sources for the government of Malta, adding 432,000,000 euro to the budget in 2018. This 'scheme' has a very low due-diligence and many doubtful Russian, Middle-eastern and Chinese have obtained a Maltese passport, which is also a European Union passport. In July 2020, the Labour government admitted this and has opted to stop it as from September 2020.[202]

Banking and finance

)_03_ies.jpg.webp)

The two largest commercial banks are Bank of Valletta and HSBC Bank Malta, both of which can trace their origins back to the 19th century. As of recently, digital banks such as Revolut have also increased in popularity.[203]

The Central Bank of Malta (Bank Ċentrali ta' Malta) has two key areas of responsibility: the formulation and implementation of monetary policy and the promotion of a sound and efficient financial system. It was established by the Central Bank of Malta Act on 17 April 1968. The Maltese government entered ERM II on 4 May 2005, and adopted the euro as the country's currency on 1 January 2008.[204]

FinanceMalta is the quasi-governmental organisation tasked with marketing and educating business leaders in coming to Malta and runs seminars and events around the world highlighting the emerging strength of Malta as a jurisdiction for banking and finance and insurance.[205]

Transport

Traffic in Malta drives on the left. Car ownership in Malta is exceedingly high, considering the very small size of the islands; it is the fourth-highest in the European Union. The number of registered cars in 1990 amounted to 182,254, giving an automobile density of 577/km2 (1,494/sq mi).[206]

Malta has 2,254 kilometres (1,401 miles) of road, 1,972 km (1,225 mi) (87.5 per cent) of which are paved and 282 km (175 mi) were unpaved (as of December 2003).[207] The main roads of Malta from the southernmost point to the northernmost point are these: Triq Birżebbuġa in Birżebbuġa, Għar Dalam Road and Tal-Barrani Road in Żejtun, Santa Luċija Avenue in Paola, Aldo Moro Street (Trunk Road), 13 December Street and Ħamrun-Marsa Bypass in Marsa, Regional Road in Santa Venera/Msida/Gżira/San Ġwann, St Andrew's Road in Swieqi/Pembroke, Malta, Coast Road in Baħar iċ-Ċagħaq, Salina Road, Kennedy Drive, St. Paul's Bypass and Xemxija Hill in San Pawl il-Baħar, Mistra Hill, Wettinger Street (Mellieħa Bypass) and Marfa Road in Mellieħa.

Buses (xarabank or karozza tal-linja) are the primary method of public transport, established in 1905. Malta's vintage buses operated in the Maltese islands up to 2011 and became popular tourist attractions in their own right.[208] To this day they are depicted on many Maltese advertisements to promote tourism as well as on gifts and merchandise for tourists.

The bus service underwent an extensive reform in July 2011. The management structure changed from having self-employed drivers driving their own vehicles to a service being offered by a single company through a public tender (in Gozo, being considered as a small network, the service was given through direct order).[209] The public tender was won by Arriva Malta, a member of the Arriva group, which introduced a fleet of brand new buses, built by King Long especially for service by Arriva Malta and including a smaller fleet of articulated buses brought in from Arriva London. It also operated two smaller buses for an intra-Valletta route only and 61 nine-metre buses, which were used to ease congestion on high-density routes. Overall Arriva Malta operated 264 buses. On 1 January 2014 Arriva ceased operations in Malta due to financial difficulties, having been nationalised as Malta Public Transport by the Maltese government, with a new bus operator planned to take over their operations in the near future.[210][211] The government chose Autobuses Urbanos de León as its preferred bus operator for the country in October 2014.[212] The company took over the bus service on 8 January 2015, while retaining the name Malta Public Transport.[213] It introduced the pre-pay 'tallinja card'. With lower fares than the walk-on rate, it can be topped up online. The card was initially not well received, as reported by several local news sites.[214] During the first week of August 2015, another 40 buses of the Turkish make Otokar arrived and were put into service.[215]

From 1883 to 1931 Malta had a railway line that connected Valletta to the army barracks at Mtarfa via Mdina and a number of towns and villages. The railway fell into disuse and eventually closed altogether, following the introduction of electric trams and buses.[216] At the height of the bombing of Malta during the Second World War, Mussolini announced that his forces had destroyed the railway system, but by the time war broke out, the railway had been mothballed for more than nine years.

Malta has three large natural harbours on its main island:

- The Grand Harbour (or Port il-Kbir), located at the eastern side of the capital city of Valletta, has been a harbour since Roman times. It has several extensive docks and wharves, as well as a cruise liner terminal. A terminal at the Grand Harbour serves ferries that connect Malta to Pozzallo & Catania in Sicily.

- Marsamxett Harbour, located on the western side of Valletta, accommodates a number of yacht marinas.

- Marsaxlokk Harbour (Malta Freeport), at Birżebbuġa on the south-eastern side of Malta, is the islands' main cargo terminal. Malta Freeport is the 11th busiest container ports in continent of Europe and 46th in the World with a trade volume of 2.3 million TEU's in 2008.[217]

There are also two man-made harbours that serve a passenger and car ferry service that connects Ċirkewwa Harbour on Malta and Mġarr Harbour on Gozo. The ferry makes numerous runs each day.

Malta International Airport (Ajruport Internazzjonali ta' Malta) is the only airport serving the Maltese islands. It is built on the land formerly occupied by the RAF Luqa air base. A heliport is also located there, but the scheduled service to Gozo ceased in 2006. The heliport in Gozo is at Xewkija.

Two further airfields at Ta' Qali and Ħal Far operated during the Second World War and into the 1960s but are now closed. Today, Ta' Qali houses a national park, stadium, the Crafts Village visitor attraction and the Malta Aviation Museum. This museum preserves several aircraft, including Hurricane and Spitfire fighters that defended the island in the Second World War.

.jpg.webp)

The national airline is Air Malta, which is based at Malta International Airport and operates services to 36 destinations in Europe and North Africa. The owners of Air Malta are the Government of Malta (98 percent) and private investors (2 percent). Air Malta employs 1,547 staff. It has a 25 percent shareholding in Medavia.

Air Malta has concluded over 191 interline ticketing agreements with other IATA airlines. It also has a codeshare agreement with Qantas covering three routes. In September 2007, Air Malta made two agreements with Abu Dhabi-based Etihad Airways by which Air Malta wet-leased two Airbus aircraft to Etihad Airways for the winter period starting 1 September 2007, and provided operational support on another Airbus A320 aircraft which it leased to Etihad Airways.

Communications

The mobile penetration rate in Malta exceeded 100% by the end of 2009.[218] Malta uses the GSM900, UMTS(3G) and LTE(4G) mobile phone systems, which are compatible with the rest of the European countries, Australia and New Zealand.

Telephone and cellular subscriber numbers have eight digits. There are no area codes in Malta, but after inception, the original first two numbers, and currently the 3rd and 4th digit, were assigned according to the locality. Fixed line telephone numbers have the prefix 21 and 27, although businesses may have numbers starting 22 or 23. An example would be 2*80**** if from Żabbar, and 2*23**** if from Marsa. Gozitan landline numbers generally are assigned 2*56****. Mobile telephone numbers have the prefix 77, 79, 98 or 99. Malta's international calling code is +356.[219]

The number of pay-TV subscribers fell as customers switched to Internet Protocol television (IPTV): the number of IPTV subscribers doubled in the six months to June 2012.

In early 2012, the government called for a national Fibre to the Home (FttH) network to be built, with a minimum broadband service being upgraded from 4Mbit/s to 100Mbit/s.[220]

Currency

Maltese euro coins feature the Maltese cross on €2 and €1 coins, the coat of arms of Malta on the €0.50, €0.20 and €0.10 coins, and the Mnajdra Temples on the €0.05, €0.02 and €0.01 coins.[221]

Malta has produced collectors' coins with face value ranging from 10 to 50 euros. These coins continue an existing national practice of minting of silver and gold commemorative coins. Unlike normal issues, these coins are not accepted in all the eurozone. For instance, a €10 Maltese commemorative coin cannot be used in any other country.

From its introduction in 1972 until the introduction of the Euro in 2008, the currency was the Maltese lira, which had replaced the Maltese pound. The pound replaced the Maltese scudo in 1825.

Tourism

Malta is a popular tourist destination, with 1.6 million tourists per year.[222] Three times more tourists visit than there are residents. Tourism infrastructure has increased dramatically over the years and a number of hotels are present on the island, although overdevelopment and the destruction of traditional housing is of growing concern. An increasing number of Maltese now travel abroad on holiday.[223]

In recent years, Malta has advertised itself as a medical tourism destination,[224] and a number of health tourism providers are developing the industry. However, no Maltese hospital has undergone independent international healthcare accreditation. Malta is popular with British medical tourists,[225] pointing Maltese hospitals towards seeking UK-sourced accreditation, such as with the Trent Accreditation Scheme.

Science and technology

Malta signed a co-operation agreement with the European Space Agency (ESA) for more-intensive co-operation in ESA projects.[226] The Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) is the civil body responsible for the development of science and technology on an educational and social level. Most science students in Malta graduate from the University of Malta and are represented by S-Cubed (Science Student's Society), UESA (University Engineering Students Association) and ICTSA (University of Malta ICT Students' Association).[227][228]

Demographics

Malta conducts a census of population and housing every ten years. The census held in November 2005 counted an estimated 96 percent of the population.[229] A preliminary report was issued in April 2006 and the results were weighted to estimate for 100 percent of the population.

Native Maltese people make up the majority of the island. However, there are minorities, the largest of which are Britons, many of whom are retirees. The population of Malta as of July 2011 was estimated at 408,000.[25] As of 2005, 17 percent were aged 14 and under, 68 percent were within the 15–64 age bracket whilst the remaining 13 percent were 65 years and over. Malta's population density of 1,282 per square km (3,322/sq mi) is by far the highest in the EU and one of the highest in the world. By comparison, the average population density for the "World (land only, excluding Antarctica)" was 54/km2 (140/sq mi) as of July 2014.

The only census year showing a fall in population was that of 1967, with a 1.7 per cent total decrease, attributable to a substantial number of Maltese residents who emigrated.[230] The Maltese-resident population for 2004 was estimated to make up 97.0 per cent of the total resident population.[231]

All censuses since 1842 have shown a slight excess of females over males. The 1901 and 1911 censuses came closest to recording a balance. The highest female-to-male ratio was reached in 1957 (1088:1000) but since then the ratio has dropped continuously. The 2005 census showed a 1013:1000 female-to-male ratio. Population growth has slowed down, from +9.5 per cent between the 1985 and 1995 censuses, to +6.9 per cent between the 1995 and 2005 censuses (a yearly average of +0.7 per cent). The birth rate stood at 3860 (a decrease of 21.8 per cent from the 1995 census) and the death rate stood at 3025. Thus, there was a natural population increase of 835 (compared to +888 for 2004, of which over a hundred were foreign residents).[232]

The population's age composition is similar to the age structure prevalent in the EU. Since 1967 there was observed a trend indicating an ageing population, and is expected to continue in the foreseeable future. Malta's old-age-dependency-ratio rose from 17.2 percent in 1995 to 19.8 percent in 2005, reasonably lower than the EU's 24.9 percent average; 31.5 percent of the Maltese population is aged under 25 (compared to the EU's 29.1 percent); but the 50–64 age group constitutes 20.3 percent of the population, significantly higher than the EU's 17.9 percent. Malta's old-age-dependency-ratio is expected to continue rising steadily in the coming years.

Maltese legislation recognises both civil and canonical (ecclesiastical) marriages. Annulments by the ecclesiastical and civil courts are unrelated and are not necessarily mutually endorsed. Malta voted in favour of divorce legislation in a referendum held on 28 May 2011.[233] Abortion in Malta is illegal. A person must be 16 to marry.[234] The number of brides aged under 25 decreased from 1471 in 1997 to 766 in 2005; while the number of grooms under 25 decreased from 823 to 311. There is a constant trend that females are more likely than males to marry young. In 2005 there were 51 brides aged between 16 and 19, compared to 8 grooms.[232]

In 2018, the population of the Maltese Islands stood at 475,701. Males make up 50.5% of the population.[235]

The total fertility rate (TFR) as of 2016 was estimated at 1.45 children born/woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1.[236] In 2012, 25.8 per cent of births were to unmarried women.[237] The life expectancy in 2018 was estimated at 83.[238]

Languages

The Maltese language (Maltese: Malti) is one of the two constitutional languages of Malta, having become official, however, only in 1934, and being considered as the national language. Previously, Sicilian was the official and cultural language of Malta from the 12th century, and the Tuscan dialect of Italian from the 16th century. Alongside Maltese, English is also an official language of the country and hence the laws of the land are enacted both in Maltese and English. However, article 74 of the Constitution states that "... if there is any conflict between the Maltese and the English texts of any law, the Maltese text shall prevail."[24]

Maltese is a Semitic language descended from the now extinct Sicilian-Arabic (Siculo-Arabic) dialect (from southern Italy) that developed during the Emirate of Sicily.[239] The Maltese alphabet consists of 30 letters based on the Latin alphabet, including the diacritically altered letters ż, ċ and ġ, as well as the letters għ, ħ, and ie.

Maltese is the only Semitic language with official status in the European Union. Maltese has a Semitic base with substantial borrowing from Sicilian, Italian, a little French, and more recently and increasingly, English.[240] The hybrid character of Maltese was established by a long period of Maltese-Sicilian urban bilingualism gradually transforming rural speech and which ended in the early 19th century with Maltese emerging as the vernacular of the entire native population. The language includes different dialects that can vary greatly from one town to another or from one island to another.

The Eurobarometer states that 97% percent of the Maltese population consider Maltese as mother tongue. Also, 88 percent of the population speak English, 66 percent speak Italian, and 17 percent speak French.[1] This widespread knowledge of second languages makes Malta one of the most multilingual countries in the European Union. A study collecting public opinion on what language was "preferred" discovered that 86 percent of the population express a preference for Maltese, 12 percent for English, and 2 percent for Italian.[241] Still, Italian television channels from Italy-based broadcasters, such as Mediaset and RAI, reach Malta and remain popular.[241][242][243]

Maltese Sign Language is used by signers in Malta.[244]

Religion

The predominant religion in Malta is Catholicism. The second article of the Constitution of Malta establishes Catholicism as the state religion and it is also reflected in various elements of Maltese culture, although entrenched provisions for the freedom of religion are made.[24]

There are more than 360 churches in Malta, Gozo, and Comino, or one church for every 1,000 residents. The parish church (Maltese: "il-parroċċa", or "il-knisja parrokkjali") is the architectural and geographic focal point of every Maltese town and village, and its main source of civic pride. This civic pride manifests itself in spectacular fashion during the local village festas, which mark the day of the patron saint of each parish with marching bands, religious processions, special Masses, fireworks (especially petards) and other festivities.

Malta is an Apostolic See; the Acts of the Apostles tells of how St. Paul, on his way from Jerusalem to Rome to face trial, was shipwrecked on the island of "Melite", which many Bible scholars identify with Malta, an episode dated around AD 60.[247] As recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, St. Paul spent three months on the island on his way to Rome, curing the sick including the father of Publius, the "chief man of the island". Various traditions are associated with this account. The shipwreck is said to have occurred in the place today known as St Paul's Bay. The Maltese saint, Saint Publius is said to have been made Malta's first bishop and a grotto in Rabat, now known as "St Paul's Grotto" (and in the vicinity of which evidence of Christian burials and rituals from the 3rd century AD has been found), is among the earliest known places of Christian worship on the island.

| (1) The religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic apostolic religion. (2) The authorities of the Roman Catholic apostolic church have the duty and the right to teach which principles are right and which are wrong. (3) Religious teaching of the Roman Catholic apostolic faith shall be provided in all state schools as part of compulsory education. |

| Chapter 1, Article 2 of the Constitution of Malta[24] |

Further evidence of Christian practices and beliefs during the period of Roman persecution appears in catacombs that lie beneath various sites around Malta, including St. Paul's Catacombs and St. Agatha's Catacombs in Rabat, just outside the walls of Mdina. The latter, in particular, were frescoed between 1200 and 1480, although invading Turks defaced many of them in the 1550s. There are also a number of cave churches, including the grotto at Mellieħa, which is a Shrine of the Nativity of Our Lady where, according to legend, St. Luke painted a picture of the Madonna. It has been a place of pilgrimage since the medieval period.

The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon record that in 451 AD a certain Acacius was Bishop of Malta (Melitenus Episcopus). It is also known that in 501 AD, a certain Constantinus, Episcopus Melitenensis, was present at the Fifth Ecumenical Council. In 588 AD, Pope Gregory I deposed Tucillus, Miletinae civitatis episcopus and the clergy and people of Malta elected his successor Trajan in 599 AD. The last recorded Bishop of Malta before the invasion of the islands was a Greek named Manas, who was subsequently incarcerated at Palermo.[248]

Maltese historian Giovanni Francesco Abela states that following their conversion to Christianity at the hand of St. Paul, the Maltese retained their Christian religion, despite the Fatimid invasion.[249] Abela's writings describe Malta as a divinely ordained "bulwark of Christian, European civilization against the spread of Mediterranean Islam".[250] The native Christian community that welcomed Roger I of Sicily[32] was further bolstered by immigration to Malta from Italy, in the 12th and 13th centuries.

For centuries, the Church in Malta was subordinate to the Diocese of Palermo, except when it was under Charles of Anjou, who appointed bishops for Malta, as did – on rare occasions – the Spanish and later, the Knights. Since 1808 all bishops of Malta have been Maltese. As a result of the Norman and Spanish periods, and the rule of the Knights, Malta became the devout Catholic nation that it is today. It is worth noting that the Office of the Inquisitor of Malta had a very long tenure on the island following its establishment in 1530: the last Inquisitor departed from the Islands in 1798 after the Knights capitulated to the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the period of the Republic of Venice, several Maltese families emigrated to Corfu. Their descendants account for about two-thirds of the community of some 4,000 Catholics that now live on that island.

The patron saints of Malta are Saint Paul, Saint Publius, and Saint Agatha. Although not a patron saint, St George Preca (San Ġorġ Preca) is greatly revered as the second canonised Maltese saint after St. Publius. Pope Benedict XVI canonised Preca on 3 June 2007. A number of Maltese individuals are recognised as Blessed, including Maria Adeodata Pisani and Nazju Falzon, with Pope John Paul II having beatified them in 2001.

Various Catholic religious orders are present in Malta, including the Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites and Little Sisters of the Poor.

Most congregants of the local Protestant churches are not Maltese; their congregations draw on the many British retirees living in the country and vacationers from many other nations. There include St. Andrew's Scots Church in Valletta (a joint Presbyterian and Methodist congregation) and St Paul's Anglican Cathedral. There are several Charismatic, Pentecostal, and Baptist churches, including the Bible Baptist Church, Knisja Evanġelika Battista, and Trinity Evangelical Church - a Reformed Baptist Church. The members of these churches are mainly Maltese.

There are also a Seventh-day Adventist church in Birkirkara, and a New Apostolic Church congregation founded in 1983 in Gwardamangia.[251]There are approximately 600 Jehovah's Witnesses.[252] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is also represented.

The Jewish population of Malta reached its peak in the Middle Ages under Norman rule. In 1479, Malta and Sicily came under Aragonese rule and the Alhambra Decree of 1492 forced all Jews to leave the country, permitting them to take with them only a few of their belongings. Several dozen Maltese Jews may have converted to Christianity at the time to remain in the country. Today, there is one Jewish congregation.[251]

There is one Muslim mosque, the Mariam Al-Batool Mosque. A Muslim primary school recently opened. Of the estimated 3,000 Muslims in Malta, approximately 2,250 are foreigners, approximately 600 are naturalised citizens, and approximately 150 are native-born Maltese.[253] Zen Buddhism and the Baháʼí Faith claim some 40 members.[251]

In a survey held by the Malta Today, the overwhelming majority of the Maltese population adheres to Christianity (95.2%) with Catholicism as the main denomination (93.9%). According to the same report, 4.5% of the population declared themselves as either atheist or agnostic, one of the lowest figures in Europe.[254] According to a Eurobarometer survey conducted in 2019, 83% of the population identified as Catholic.[3] The number of atheists has doubled from 2014 to 2018. Non-religious people have a higher risk of suffering from discrimination, such as lack of trust by society and unequal treatment by institutions. In the 2015 edition of the annual Freedom of Thought Report from the International Humanist and Ethical Union, Malta was in the category of "severe discrimination". In 2016, following the abolishment of blasphemy law, Malta was shifted to the category of "systematic discrimination" (which is the same category as most EU countries).[255]

Inbound migration

| Foreign population in Malta | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % total | |||||||||||||||||

| 2005 | 12,112 | 3.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 20,289 | 4.9% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 98,918 | 21.0% | |||||||||||||||||

| 2020 | 119,261 | 23.17% | |||||||||||||||||

Most of the foreign community in Malta, predominantly active or retired British nationals and their dependents, is centred on Sliema and surrounding modern suburbs. Other smaller foreign groups include Italians, Libyans, and Serbians, many of whom have assimilated into the Maltese nation over the decades.[256]

Malta is also home to a large number of foreign workers who migrated to the island to try and earn a better living. This migration was driven pre-dominantly at a time where the Maltese economy was steadily booming yet the cost and quality of living on the island remained relatively stable.

In recent years however the local Maltese housing index has doubled[257] pushing property and rental prices to very high and almost unaffordable levels in the Maltese islands with the slight exception of Gozo. Salaries in Malta have risen very slowly and very marginally over the years making life on the island much harder than it was a few years ago.

As a direct result, a significant level of uncertainty exists among expats in Malta as to whether their financial situation on the island will remain affordable in the years going forth, with many already barely living paycheck to paycheck and others re-locating to other European countries altogether.

Since the late 20th century, Malta has become a transit country for migration routes from Africa towards Europe.[258]

As a member of the European Union and of the Schengen Agreement, Malta is bound by the Dublin Regulation to process all claims for asylum by those asylum seekers that enter EU territory for the first time in Malta.[259]

Irregular migrants who land in Malta are subject to a compulsory detention policy, being held in several camps organised by the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM), including those near Ħal Far and Ħal Safi. The compulsory detention policy has been denounced by several NGOs, and in July 2010, the European Court of Human Rights found that Malta's detention of migrants was arbitrary, lacking in adequate procedures to challenge detention, and in breach of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights.[260][261]

In January 2014, Malta started granting citizenship for a €650,000 contribution plus investments, contingent on residence and criminal background checks.[262]

This 'golden passport' citizenship scheme has been criticized on multiple occasions as a fraudulent act by the Maltese Government since it has come under scrutiny for selling citizenship to a number of dubious and/or criminal individuals from non-European nation countries.[263]

Concerns as to whether the Maltese citizenship scheme is allowing an influx of such individuals into the greater European Union have been raised by both the public as well as the European Council on multiple occasions.[264]

On 8 September 2020, Amnesty International criticized Malta for "illegal tactics" in the Mediterranean, against immigrants who were attempting to cross from North Africa. The reports claimed that the government's approach might have led to avoidable deaths.[265]

Outbound migration

In the 19th century, most emigration from Malta was to North Africa and the Middle East, although rates of return migration to Malta were high.[266] Nonetheless, Maltese communities formed in these regions. By 1900, for example, British consular estimates suggest that there were 15,326 Maltese in Tunisia, and in 1903 it was claimed that 15,000 people of Maltese origin were living in Algeria.[267]