Marsannay wine

Marsannay wine is produced in the communes of Marsannay-la-Côte, Couchey and Chenôve in the Côte de Nuits subregion of Burgundy. The Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) Marsannay may be used for red and rosé wine with Pinot noir, as well as white wine with Chardonnay as the main grape variety. Red wine accounts for the largest part of the production, around two-thirds. Marsannay is the only village-level appellation which may produce rosé wines, under the designation Marsannay rosé.[1] All other Burgundy rosés are restricted to the regional appellation Bourgogne. There are no Grand Cru or Premier Cru vineyards in Marsannay. The Marsannay AOC was created in 1987, and is the most recent addition to the Côte de Nuits.[2]

History

Ancient times

The edict issued by the Roman emperor Domitian in 92AD prevented the planting of new vines outside Italy. He had the vines in Burgundy partly uprooted to avoid competition. The remaining vineyards were enough to meet the locals' needs. But Probus revoked the edict in 280. In 312, a disciple of Eumène wrote the first description of the Côte d'Or vineyard.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

From the early 6th century, the introduction of Christianity had encouraged vineyard expansion with large areas attached to the abbeys dedicated to this. Thus the Cîteaux Abbey (founded in 1098) with plantations in Côte d'Or.[3] In the year 1395, Philip the Bold decided to improve the quality of wines and prohibited the cultivation of the Gamay grape on his land in favor of Pinot noir.[3] Finally in 1416, Charles VI issued a decree which fixed a limit on the production of Burgundy wine.[4] In 1422, according to the records, the harvest took place in August in Côte de Nuits.[5] Upon the death of Charles the Bold, the Burgundy vineyard was annexed back to France during the reign of Louis XI.

Modern period

Also in 1700, the intendant Ferrand wrote a "memo instructing the Duke of Burgundy", indicating to him that the best wines in this province came from the "vineyards [which] border on Côte de Nuits and Côte de Beaune"[.[6]

Contemporary period

19th century

In the 1830s and 1840s, the snout moth came and attacked the vine leaves. It was followed by a fungal disease called powdery mildew (Oidium).[7] The vintage year 1865 produced wines with very high natural levels of sugar and very early harvests.[5] At the end of the century two new vine scourges emerged. The first was mildew, another fungal disease, and the second was phylloxera. This burrowing insect, native of North America, severely damaged the vineyard.[7]

20th century

The mildew caused huge problems in 1910. Emergence of the high clearance tractors (enjambeur) in the 1960s and 1970s, replacing horses. Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) created in 1987.[8] The techniques in wine making and oenology have significantly evolved in the past 50 years (with green harvesting, sorting tables, stainless steel tanks, electric and pneumatic presses...).

21st century

With the heat wave of 2003, in some areas the harvests began in mid-August, a month in advance; these were very early harvests that, according to the records, had not been seen since 1422 and 1865.[5]

Climate

The climate is temperate with a slight continental tendency.

Vineyard

Presentation

The vineyard extends over the Marsannay-la-Côte, Chenôve and Couchey communes. It comprises 445 acres (180 ha) of red and rosé wines, and 69 acres (28 ha) of white wines.[8]

Assortment of grape varieties

The Pinot noir variety constitutes exclusively the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC) red wines. It consists of small dense pine-shaped bunches[9] composed of dark blue ovoid grapes.[9] It is a delicate variety that is susceptible to major diseases, particularly to mildew, the parasitic rougeot, gray mold (on bunches and leaves), and plant hopper.[10] This variety, which requires careful removing of unwanted buds, tends to produce a large number of grapillons.[10] It takes full advantage of the vegetative cycle and ripens at an early stage. There is a high potential of an accumulation of sugars is for an only average and sometimes insufficient acidity to reach maturity. The wines are quite powerful, rich, colorful and to be kept for maturing.[11] They are generally moderately tannic.

The chardonnay variety constitutes the white wines of the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AOC). Its bunches are relatively small, cylindrical, less dense than those of the Pinot noir,[12] and consist of irregular, rather small, golden yellow grapes.[12] Like the Pinot noir, from maturation of the first stage like the Pinot noir, it adapts better to the humidity of the end of the season with a better resistance against rotting unless undergoing vigorous growth. It is susceptible to mildew and the flavescence dorée bacterial disease. It buds just before the Pinot noir, which also makes it sensitive to spring frosts. The sugar contents of the berries can achieve high levels while retaining a significant acidity, which allows for wines to be particularly well balanced, powerful, detailed, and ropy, with much volume.[10]

Mechanical work

This work begins with pruning using the Guyot simple system, with a cane of five to eight buds and a spur of one to three buds[13]], followed by the drawing of the vine shoots.The vine shoots are removed and then are either burned or placed in the middle of the row to be crushed. Next is the repairs process, then the bending of the canes.Eventually, after the bending of the canes, grafting is performed. Pruning may begin once the vines have begun growing. This method offers the possibility of somewhat regulating production.[13] The vines are tied up once they have already grown significantly; this is generally carried out two or three times. Green harvesting is practised more and more in this appellation. This process is carried out in order to regulate production and especially to increase the quality of remaining grapes.[13] The manual labour method in the vineyard is finished upon completion of the all-important harvesting stage.

Travail mécanique

The high clearance tractors (enjambeur) are a great help. The different steps consist of crushing the vine shoots after they have been taken and placed in the middle of the row; a hole being made in the auger, where the vines stocks are missing, in order to plant grafts in the spring; ploughing or scraping, done in order to aerate the soil and eliminate any weeds; chemical weeding to kill weeds; several treatments of the vines, done in order to protect against fungal diseases (mildew, powdery mildew, grey rot, etc.) and some insects (Eudemis and Cochylis); regular trimming consisting in snipping or cutting excess vine branches (shoots) using the trellising system; mechanical harvesting carried out with a harvesting machine or a grape picking head mounted on a high clearance tractor (enjambeur).[13]

Yield

The yield is around 1,620 litres per acre for red wine and 1,820 litres per acre for white wine.

Minimum and maximum alcoholic strength by volume

| AOC | Red | Red | White | white | Rosé | Rosé |

| Alcoholic strength by volume | minimal | maximal | minimal | maximal | minimal | maximal |

| Village | 10,5% | 13,5% | 11% | 14% | 10,5% | 13% |

Wine making and aging

Here are the general methods of wine making in this appellation. There are however small differences in approach amongst the different growers and traders.

Red wine making

The grape harvest is done when the grapes are ripe and is done manually or mechanically. The manual harvest is for the most part sorted, either at the vineyard or at the cellar with a sorting table, thereby removing the rotten grapes or insufficiently mature ones.[13] The manual harvest is usually broken and then placed in vats. Cold pre-fermentation maceration is sometimes carried out. The fermentation can now begin, usually after the application of yeast. Then begins the work of extracting the polyphenols (tannins, anthocyanins) and other qualitative aspects of the grape (polysaccharides etc.).[13] The extraction is done by pigeage, an operation which consists in punching the cap into the fermenting juice using a wooden tool or nowadays a hydraulic system. More commonly, the extraction is conducted by reassemblies, an operation which involves pumping the juice from the bottom of the tank to water the cap and thus wash away the qualitative components of the grapes. The fermentation temperature may be higher or lower depending on the practices of each winemaker with an average of 28° to 35° at fermentation peak.[13] Chaptalization is carried out if the natural alcohol content is not enough: this process is regulated.[13] The alcoholic fermentation is followed by racking which produces free-run wine and press wine. The malolactic fermentation takes place after, but it is temperature-dependent. The wine is racked and placed in barrels or tanks for maturing. The maturing continues for several months (12 to 24 months)[13] and the wine is refined, filtered and bottled.

White wine making

Like for red wine, the harvest is done manually or mechanically and can be sorted. The grapes are then transferred to a press for pressing. Once the grape must is in the tank, the settling is usually carried out after enzymes are added. At this stage, a pre-fermentary cold stabulation (about 10° to 12° for several days) may be sought to facilitate the extraction of flavors.[13] But usually after 12 to 48 hours, the clear juice is racked and fermented.[13] Fermentation takes place with special monitoring of the temperature, which should remain more or less stable (18° to 24°).[13] Chaptalization is also practiced to increase the alcoholic strength if necessary. Malolactic fermentation is carried out in barrels or vats. The wines are aged "on lees", in barrels, in which the winemaker regularly conducts a stirring (bâtonnage), or a re-suspension of the lees.[13] This process lasts for several months during the maturing of the white wine. In the end, the wine is filtered to make it less cloudy[13] The process ends with bottling.

Rosé wine making

Manual or mechanical harvesting with either Pinot noir or Gamay. The grapes are sometimes sorted. Two methods are used: either pressing (Rosé pressing), or placing the harvest in a tank for an early maceration: bleeding off (bleeding rosé), made with the juice drawn from the tank. Fermentation is done in the tank, like the white wine, and then followed by monitoring of the temperature, chaptalization, etc. Malolactic fermentation is then carried out. Maturing takes place in vats, (sometimes in barrels). Finally, the wine is filtered and bottled.

Marketing

Production yields 550,000 liters of red wine, 250,000 litres of rosé wine and 130,000 litres of white wine.[8] The marketing of this appellation is done through various sales channels: in the vaults of the wine-grower, in wine fairs (independent winemakers, etc.), in food fairs, for export in the Cafés-Hôtels-Restaurants (CHR) in large and medium-sized stores (GMS).

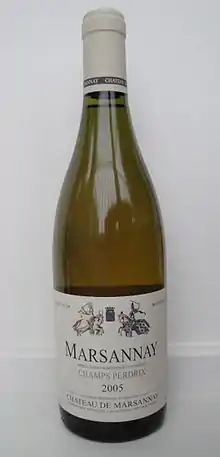

Photos

Chateau de Marsannay surrounded by vines

Chateau de Marsannay surrounded by vines

Production

In 2008, 227 hectares (560 acres) of vineyard surface was in production for Marsannay wine, of which 32.01 hectares (79.1 acres) were used for Marsannay rosé. In the same year, 9,650 hectoliter of wine was produced, of which 6,455 hectoliter red wine, 1,481 hectoliter rosé wine, and 1,714 hectoliter white wine.[14] The total amount produced corresponds to just under 1.3 million bottles of wine, of which just over 850,000 bottles of red wine, just under 200,000 bottles of rosé, and a little over 200,000 bottles of white wine.

AOC regulations

The AOC regulations allow up to 15 per cent total of Chardonnay, Pinot blanc and Pinot gris as accessory grapes in the red wines, and Pinot gris may be used in the rosé wines,[2] but this not very often practiced. For white wines, both Chardonnay and Pinot blanc are allowed, but most wines are likely to be 100% Chardonnay. The allowed base yield is 40 hectoliter per hectare of red wine and 45 for rosé and white wine. The grapes must reach a maturity of at least 10.5 per cent potential alcohol for red and rosé wine and 11.0 per cent for white wine.

See also

References

- BIVB: Marsannay, accessed on 17 November 2009

- AOC regulations, last updated 1989

- Le Figaro et La Revue du vin de France (2008) : Vins de France et du monde (Bourgogne : Chablis), L'histoire, p.26.

- Site du BIVB : Historique Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, consulted on 24 November 2008.

- La Revue du vin de France n°482S : Le Millésime 2003 en Bourgogne, p.109

- Marcel Lachiver, opcit, p.370.

- Le Figaro and La Revue du vin de France (2008) : Vins de France et du monde (Bourgogne : Côte de Beaune), L'histoire, p.26.

- Site du BIVB

- Christian Pessey, Vins de Bourgogne, La vigne et le vin « Pinot noir », p.12

- Catalogue des variétés et clones de vigne cultivés en France ENTAV, Éditeur

- Christian Pessey, Vins de Bourgogne, La vigne et le vin « Pinot noir », p.13

- Christian Pessey, Vins de Bourgogne, La vigne et le vin « Chardonnay », p.13

- Conduite et gestion de l'exploitation agricole, cours de viticulture du lycée viticole de Beaune (1999-2001). Baccalauréat professionnel option viticulture-oenologie.

- BIVB: Les Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée de Bourgogne, accessed on 17 November 2009

Bibliography

- Christian Pessey : Vins de Bourgogne (Histoire et dégustations), édition : Flammarion, Paris, 2002, Histoire (91 pages) et Dégustations (93 pages) ISBN 2080110179

- Le Figaro et La Revue du Vin de France : Les vins de France et du monde (20 volumes), n°6 (Chablis), 96 pages, Édité par La société du Figaro, Paris, 2008, ISBN 978-2-8105-0060-4

- Le Figaro et La Revue du Vin de France : Les vins de France et du monde (20 volumes), n°11 (Côtes de Beaune), 96 pages, Édité par La société du Figaro, Paris, 2008, ISBN 978-2-8105-0065-9

- Marcel Lachiver, Vins, vignes et vignerons. Histoire du vignoble français, Éd. Fayard, Paris, 1988, pp. 289, 367, 368, 372, 374. ISBN 2-213-02202-X