Mary Mildred Williams

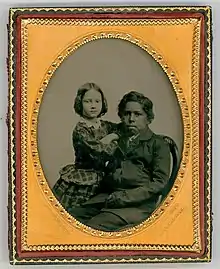

Mary Mildred Williams (born Botts, c. 1847 - 1921) was an enslaved American born in Virginia, later freed through the efforts of her father. Based on the public perception of her as a white child after photographs of her were published in the press, she was compared to the fictional character of Ida May and used by abolitionists before the Civil War to advance the cause of ending slavery in the United States.

Early life

Mary Mildred Williams, born Botts in 1847, was the second child of Seth Botts and his wife Elizabeth (née Nelson).[1] Seth and Elizabeth were married in the early 1840s.[2] Williams had an older brother, Oscar, and a younger sister, Adelaide (also known by her middle name of Rebecca).[3]

At the time of Williams’ birth, her mother, brother, grandmother, and aunts were enslaved in Prince William County, Virginia, near Washington, while her father was enslaved in neighboring Stafford County.[3]

The maternal side of Williams' family were the subjects of protracted legal battles centering around the descendants of Jesse and Constance Cornwell.[4][5] Through her father, Humphrey Calvert, Constance purchased Williams' maternal great-grandmother, Lettice (or "Letty"), and grandmother, Prudence Bell (also known as "Prucy" or "Pru"), between 1809-1812.[6][7] According to court and census records, Williams' mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Prudence and a white man named Thomas Nelson, who was Cornwell's executor.[1][8]

Upon becoming free at the age of seven in 1855, Williams and her family joined her father, who had escaped Virginia and changed his name to Henry Williams, in Boston.[1]

Between the 1855 Massachusetts state census and 1860 federal census, the Botts family changed their name to Williams.[1]

In the summer of 1860, Williams’ older brother Oscar died from tuberculosis.[1]

Legal proceedings

When Constance Cornwell died in 1825, she willed Williams' maternal grandmother, Prudence, her two children Elizabeth (Williams' mother) and Albert, and "the increase of the females forever" to her daughter Kitty Cornwell's eldest son John Cornwell.[7] She specified in her will that the inherited slaves (or their children) could not be sold, and if he were to try they would be freed.[9] Because John was not of age at the time of Constance's death, her slaves were to be retained by the executor of her will, Thomas Nelson, until John turned 21 in 1830.[9]

However, Constance’s will was disputed by her children, and a legal battle began in 1835.[9] The legal disputes continued for years, and Prudence and her children remained in Nelson’s possession. When Nelson passed away in 1845, J.C. Weedon, his qualified administrator, took possession of Prudence along with her children and grandchildren.[10] John Cornwell instituted proceedings to recover the family from Weedon in 1847, as they had been willed to him by Constance.[10] The case of Nelson’s Adm’r v. Cornwell was decided by the Virginia Supreme Court in October 1854.[11] It awarded all of the property to John, aided by Prudence’s husband and Mary’s father, Seth Botts, then known as Henry Williams.[12]

Freedom

In 1855, at age seven, Williams became free through the efforts of her father, Seth Botts, an escaped slave. Botts had escaped bondage in 1850, renamed himself to Henry Williams, and spent the subsequent four years seeking out the help of prominent abolitionists in Boston in his quest to secure his family’s freedom.[13] Williams, with the help of his wealthy backers, bought the property from Cornwell and ended his family’s bondage. This is how Henry’s daughter, Mary Mildred Williams, came to the attention of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner.[13]

Relationship to the abolitionist movement

On March 1, 1855 a letter from Charles Sumner dated February 19 addressed ‘Dear Doctor’ was published in the New-York Daily Times (originally published in the Boston Telegraph on February 27) that had accompanied a daguerreotype of Williams. In the letter, Sumner declares: “The daguerreotype mentioned in the following letter is a portrait of one of the family referred to, a most beautiful white girl, with high forehead, straight hair, intellectual appearance, and decidedly attractive features.”[14] In a subsequent article March 9, 1855, reporters of the New-York Daily Times expressed “astonishment” that she was “ever held a slave.”[15]

In early 1855, articles were published about her in the Boston Telegraph and the New York Times, and copies of her photograph were widely publicized.[16][17] After her photograph was published, she accompanied Senator Charles Sumner, a leading abolitionist, on a publicity tour.[18]

The photo and tour made her famous, and she was compared to fictional character Ida May, the child hero of the then popular novel about a white girl kidnapped into slavery, Ida May: a Story of Things Actual and Possible by Mary Hayden Pike (1854). She was described in the words of a columnist in Frederick Douglass’ Paper as ‘perfectly white, and on that account produces intense excitement. We see daily white fugitives and the cupidity of a slaveholder would suffer him to keep anyone, even his mother, in slavery. When white men learn this, and that their own liberties are in danger, then they will see the reasonable-ness of an unconditional emancipation.’ [19] Abolitionists emphasized her perceived whiteness to enlist sympathy, as well as to frighten Northerners that any child, regardless of appearance, might be snatched away and made a slave.

On May 19 and 20, 1856, Sumner spoke in the Senate comparing Southern political positions to the sexual exploitation of slaves then taking place in the South. Two days later Sumner was beaten almost to death on the floor of the Senate in the Capitol by Representative Preston Brooks from South Carolina, known as a hothead.[17]

Adulthood and death

By 1865, Williams had moved to Lexington, Massachusetts, along with her parents and sister.[20] Five years later, she was living with her mother and sister in Hyde Park, a suburb of Boston.[21] It is unclear why her father did not join them there.

Williams as well as her mother and sister were listed as white in the 1870 census.[21] Both she and her mother identified as white women for the remainder of their lives.[22] When her mother died in 1892, the death certificate listed her maiden name as that of her white father: “Elizabeth A. (Nelson) Williams.”[22]

Williams never married nor had children.[23] She became a clerk at Boston’s Registry of Deeds, where she worked until at least 1900.[22]

She rented an apartment in the Eleventh Ward of Boston, and according to the 1900 census, she lived there with her “partner,” Mary Maynard. Maynard worked as a bookkeeper and probation officer and was listed as the child of Irish and English immigrants.[22]

Williams died in 1921 and was buried in Boston.[23]

See also

References

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 64. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Morgan-Owens, Jessie (2019). "The Enslaved Girl Who Became America's First Poster Child". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 55. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. ISSN 1526-3894. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 63–67. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. ISSN 1526-3894. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Appeals, Virginia Supreme Court of (1892). Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. D. Bottom, Superintendent of Public Print. p. 725.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Morgan-Owens, Jessie (2019). "Constance Cornwell". Girl in Black and White: The Story of Mary Mildred Williams and the Abolition Movement. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-393-60925-7.

- "Nelson's Adm'r vs. Cornwell". Virginia Reports, Annotated (PDF). 1854. p. 392.

- "Nelson's Adm'r vs. Cornwell". Virginia Reports, Annotated (PDF). 1854. p. 395.

- Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (1892). Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. D. Bottom, Superintendent of Public Print. p. 726.

- Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (1892). Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. D. Bottom, Superintendent of Public Print. p. 733.

- "Nelson's Adm'r v. Cornwell, 52 Va. 724, 11 Gratt. 724 (1854)". Caselaw Access Project. 1854. Retrieved 2020-08-15.

- Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals (1892). Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia. D. Bottom, Superintendent of Public Print. p. 751.

- Cohen, Joanna (2020). "Seeing Worth and Worth Seeing: Capitalism, Race, and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century America". Reviews in American History. 48: 27–35. doi:10.1353/rah.2020.0004 – via Project MUSE.

- "Letter from Hon. Charles Sumner - Another Ida May". New-York Daily Times. March 1, 1855. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "A White Slave from Virginia". New-York Daily Times. March 9, 1855. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Gage, Joan. "A White Slave Girl "Mulatto Raised by Charles Sumner"". Mirror of Race. Retrieved July 5, 2016.

- Morgan-Owens, Jessie (February 19, 2015). "Poster Child: There's Something About Mary". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved July 6, 2016.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 77. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- "Frederick Douglass' Paper". Rochester, N.Y. March 16, 1855. p. 3. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 77. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. ISSN 1526-3894. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 78. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. ISSN 1526-3894. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Mitchell, Mary Niall (2013). "The Real Ida May: A Fugitive Tale in the Archives". Massachusetts Historical Review. 15: 79. doi:10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054. ISSN 1526-3894. JSTOR 10.5224/masshistrevi.15.1.0054.

- Morgan-Owens, Jessie (March 2019). "The Enslaved Girl Who Became America's First Poster Child". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

External links

- Ida May: A Story of Things Actual and Possible Published 1854