Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort (1630–1715)

Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort (baptised 16 December 1630 – 7 January 1715)[1] also known by her other married name of Mary Seymour, Lady Beauchamp and her maiden name Mary Capell, was an English noblewoman, gardener and botanist.[2][3]

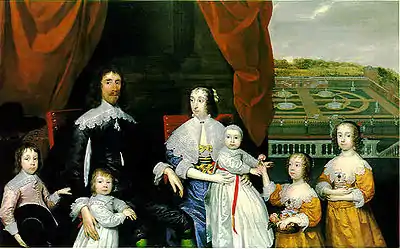

The Duchess of Beaufort | |

|---|---|

Engraving by Joseph Nutting after Robert Walker | |

| Born | baptised 16 December 1630 |

| Died | 7 January 1715 (aged 84) |

| Resting place | St Michael and All Angels Church, Badminton |

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | 12 volume herbarium and introduction of exotic species to English gardening |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 9, including Charles, Mary, Henrietta, and Anne |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Aristocrat and botanist |

| Influences | |

Early life

Mary was born in Hadham Parva, Hertfordshire, sometime before 16 December 1630, on which date she was baptised. She was the daughter of Sir Arthur Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Hadham and Elizabeth Morrison.[1]

Life

%252C_Later_Duchess_of_Beaufort%252C_and_Her_Sister_Elizabeth_(1633%E2%80%931678)%252C_Countess_of_Carnarvon.jpg.webp)

On 28 June 1648, Mary married her first husband Henry Seymour, Lord Beauchamp, and they had one son and one daughter. Her husband was a Royalist, imprisoned during the English Civil War. Her second husband, whom she married on 17 August 1657 was Henry Somerset, who became 1st Duke of Beaufort, by whom she had six children.[1]

During the Popish Plot, she was required in her husband's absence to call out the militia, to deal with a false alarm of a French invasion at the Isle of Purbeck, and did so "in a state of deadly fear". The supposed invasion, like much that happened (or failed to happen) during the Plot, was simply the result of public hysteria.[4] Despite this moment of panic, in general she maintained a detached and rational attitude to the Plot, expressing her amazement that the informer William Bedloe, whom she knew to be "a villain whose word would not have been taken at sixpence", should now have "power to ruin any man".[5] She attended the trial of the Catholic barrister Richard Langhorne, presumably in case Bedloe, a bitter enemy of her husband, made any charges against him, and took notes of the evidence. When Bedloe protested at her presence, the Lord Chief Justice, William Scroggs, pointed out that the trial was open to the public, and asked irritably what a woman's notes amounted to anyway: "no more than her tongue, truly".[6]

She was a notoriously exacting employer "striking terror in the hearts of her servants":[7] every day she would do a tour of the house and grounds, and any servant not found hard at work was instantly dismissed.[8] Even neighbouring landowners held her in awe, and were anxious not to cross her.[8]

Botanist and gardener

The Duchess of Beaufort was one of Britain's earliest distinguished lady gardeners, Alice Coats observes.[9] She began seriously to collect plants in the 1690s,[10] and her interest in gardening intensified in her widowhood.[11] She had the assistance of such well-known gardeners and botanists as George London and Leonard Plukenet; seeds came to her from the West Indies, South Africa, India, Sri Lanka, China and Japan.[12] In 1702, she engaged the services of William Sherard as tutor for her grandson, "hee loving my diversion so well. Sherard helped introduce more than 1500 plants, most of them greenhouse subjects, to her collection, at Badminton House or at Beaufort House, Chelsea. Sir Robert Southwell, Sir Hans Sloane and Jacob Bobart are all known to have sought her assistance in growing and identifying plants from unidentified seeds, some of which had come to them through the Royal Society of London.[13]

Her London house was next to that of Sir Hans Sloane, making her a neighbour of the Chelsea Physic Garden.[14] Her herbarium, in twelve volumes, 'gathered and dried by order of Mary Duchess of Beaufort',[15] she bequeathed to Sir Hans Sloane, by whose bequest it came to the Natural History Museum.[16] Her two-volume florilegium of drawings by Everard Kickius of her most choice exotics remains in the library at Badminton.[17] Among her introductions to British gardening, most of which were greenhouse plants, are Pelargonium zonale one of the parents of the zonal pelargoniums of gardens, ageratum and the Blue Passion Flower (Passiflora caerulea).[18]

She is also notable for being one of the earliest women known to have her own collection of the Philosophical Transactions, the journal of the Royal Society of London.[19]

Personal life

%252C_1st_Duke_of_Beaufort%252C_KG%252C_PC.jpg.webp)

With her first husband, Henry Seymour, Lord Beauchamp (c. 1626–1654), she had two children:

- William Seymour, 3rd Duke of Somerset (d. 1671)

- Lady Elizabeth Seymour (c. 1655–1697) married Thomas Bruce, 2nd Earl of Ailesbury

With her second husband, Henry Somerset, 1st Duke of Beaufort (1629–1700), she had:

- Henry Somerset, Lord Herbert (bef. 1660), who died as infant

- Charles Somerset, Marquess of Worcester (1660-1698), who had a military and political career.

- unknown daughter Somerset (b. bef. 1663)

- Lady Mary Somerset (1664-1733), who married James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormonde

- Lady Henrietta Somerset (c.1670-1715), who married firstly, Lord Ilbracken, son of Henry O'Brien, 7th Earl of Thomond, and secondly, Henry Howard, 6th Earl of Suffolk

- Lord Arthur Somerset (1671-1743), who married Mary Russell in 1695, daughter of William Russell, 1st and last Bt., and Hesther Rouse, daughter of Sir Thomas Rouse, 1st Bt. (1608-1676). Their daughter, Mary Somerset, was the grandmother of Sir Charles William Rouse Boughton, 1st and 9th Bt..

- Lady Anne Somerset (1673–1763), who married Thomas Coventry, 2nd Earl of Coventry

Mary was widowed in 1700 and later died on 7 January 1715 in Chelsea, London, England at the age of 84. She was buried at St Michael and All Angels Church in Badminton, Gloucestershire.

Legacy and descendants

The genus Beaufortia, erected in the 19th century by Robert Brown to describe some Myrtaceous plants of Southwest Australia, commemorates her.

Her portrait was painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller in 1708. Sir Peter Lely's portrait of the Duchess with the Countess of Carnarvon is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[20]

References

- "Mary Capell". ThePeerage.com. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- Kell, P. E. "Somerset, Mary, duchess of Beaufort". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40544. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Molly McClain, Beaufort: The Duke and His Duchess (Yale University Press, 2001)

- Kenyon, J.P. The Popish Plot Phoenix Press reissue 2000 p.123

- Kenyon pp.109–110

- Kenyon p.189

- Fraser, Antonia King Charles II Mandarin edition 1993 p.331

- Fraser p.331

- Coats, Garden Shrubs and Their Histories (1964) 1992:212 (brief notice of her gardening abilities).

- Douglas Chambers, "'Storys of Plants': The assembling of Mary Capel Somerset's botanical collection at Badminton" Journal of the History of Collections, 1997

- Alice Coats remarks that "she would probably have been greatly annoyed had she known that Aiton was to date the year of her introductions from the date of her husband's death, not of her own." (Coats (1964) 1992:212); Aiton's work was Hortus Kewensis.

- Chambers 1997.

- Julie Davies, "Botanizing at Badminton House: The Botanical Pursuits of Mary Somerset, First Duchess of Beaufort" in Domesticity in the Makingof Modern Science, ed. Donald L. Opitz, Staffan Bergwik, Brigitte Van Tiggelen (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) p.33.

- Noted by R Stungo, "Recording the Aloes at Chelsea. A Singular Solution to a Difficult Problem" Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 1996.

- Paul A. Fryxell, "The typification and application of the Linnaean binomials in Gossypium", Brittonia 20.4 (October–December 1968).

- "Duchess of Beaufort's Hortus Siccus". Natural History Museum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015.

- G. Cottesloe and D. Hunt The Duchess of Beauforts Flowers (Exeter, Webb and Bower), 1983.

- Coats (1964) 1992:212.

- Davies, "Botanizing at Badminton House" p.30.

- "Sir Peter Lely (Pieter van der Faes) | Mary Capel (1630–1715), Later Duchess of Beaufort, and Her Sister Elizabeth (1633–1678), Countess of Carnarvon | The Met". metmuseum.org. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

| Preceded by New title |

Duchess of Beaufort 2 December 1682 – 21 January 1700 |

Succeeded by Vacant until 7 July 1702 Mary Sackville Somerset |

| Preceded by New title |

Dowager Duchess of Beaufort 21 January 1700 – 7 January 1715 |

Succeeded by Mary Osborne Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort |