Matilda of Swabia

Matilda of Swabia (German: Mathilde von Schwaben; c. 988/989 – 29 July 1032), a member of the Conradine dynasty, was Duchess of Carinthia by her first marriage with Duke Conrad I and Duchess of Upper Lorraine by her second marriage to Duke Frederick II. She played an active role in promoting her son, Duke Conrad the Younger, as a candidate for the German throne in 1024 and to this end corresponded with King Mieszko II of Poland.

Family

Matilda was the daughter of Duke Herman II of Swabia (d. 1003) and his wife Gerberga (c.965/966–1019), a daughter of King Conrad I of Burgundy.[1] She had many illustrious relatives. Through her father, Matilda was descended from the Ottonian king Henry the Fowler; through her mother from King Louis IV of France and Charlemagne.

After the death of Emperor Otto III in 1002, Matilda's father, Duke Herman, opposed the election of her cousin Duke Henry IV of Bavaria as German king, and promoted himself as a rival candidate for the throne. Herman and Henry both claimed descent from Henry the Fowler, progenitor of the Ottonian dynasty.[2]

Life

About 1001/02 Matilda married Conrad of Carinthia, son of Duke Otto I, a member of the Salian dynasty. Conrad supported her father's bid for the German throne in 1002.[3] Their marriage was possibly consanguineous[4] and therefore was condemned by Henry II (her father's rival who was now crowned German king) at the Synod of Thionville in January 1003.[5] A heated debate broke out; nevertheless, the couple remained together until Conrad's death in 1011.

After Duke Conrad died, his minor son with Matilda, Conrad the Younger, was passed over in the succession for the Carinthian duchy. Instead King Henry II ceded the duchy to Count Adalbero of Eppenstein, who was married to Matilda's sister, Beatrice.[6] Matilda had Conrad the Younger placed in the care of one of his Salian relative Conrad the Elder (the future king Conrad II Germany). A few years later (c.1016/7), Matilda's sister Gisela of Swabia married Conrad the Elder. Matilda maintained good relations with the couple. In 1019, her brother-in-law supported her son, Conrad the Younger, when he tried to reclaim Carinthia from Duke Adalbero. However, the attempt was unsuccessful and possibly caused Conrad the Elder to go into exile.[7]

About 1012/13, Matilda herself had married her second husband, Count Frederick of Bar, the son of Duke Theodoric I of Upper Lorraine.[8] This marriage was also consanguineous. Frederick succeeded his father in 1019; he is usually said to have died c. 1026, although it is possible that he lived until 1033.[9]

The Salian unity came to an end, when in 1024 Emperor Henry II died without heirs: both Matilda's brother-in-law Conrad the Elder and her son Conrad the Younger promoted themselves as candidates for the throne as descendants of Henry the Fowler. Conrad the Elder was elected King of the Romans (as Conrad II) at an assembly at Kamba (near Oppenheim) in Rhenish Franconia on 4 September 1024. Conrad the Younger refused to accept the new king and his mother Matilda, with her second husband Frederick and his Lorraine entourage, left the site in protest. Duke Frederick continued to support Conrad the Younger, as did Conrad's cousin, Duke Ernest II of Swabia.[10]

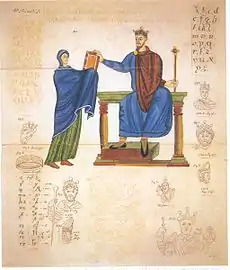

Matilda herself remained active on her son's behalf. Between 1025 and 1027 she opened negotiations with the new Polish king Mieszko II Lambert, who was also at odds with Conrad the Elder (King Conrad II), as he refused to recognise Mieszko as king and even demanded the Polish regalia from him. While Mieszko's rule was not only questioned by Conrad but also by his own Piast relatives, Matilda presented him with a valuable liturgical manuscript (the Liber de Officiis divinis). The dedicatory page of the book contained a letter from Matilda to Mieszko (Epistola ad Mathildis Suevae Misegonem II Poloniae Regem) in which she named him a distinguished king, praised him for his building of new churches, and knowledge of Latin, and wished him strength against his enemies.[11] The dedicatory page also contained a miniature depicting Matilda giving the book to Mieszko, who is shown wearing a crown and seated on a throne.[12]

Matilda's gift had the desired effect, and Mieszko promised to take military action. Several clashes of arms followed; by 1028, however, Emperor Conrad II had defeated all his opponents. By 1030 Matilda seems to have been on good terms with Conrad II again. She joined him and her sister, Empress Gisela, at the imperial court at Ingelheim in Easter 1030.[13] In 1035, Emperor Conrad II finally deprived Adalbero of Carinthia, for rebelling against him, and restored Conrad the Younger to the duchy.

Following an entry in the Annalista Saxo, Matilda is sometimes said to have married a third time, c.1026, to Count Esico of Ballenstedt.[14] She thereby would be the progenitor of the Saxon House of Ascania; nevertheless, this is not possible if her first husband Frederick lived until 1033.

Death

Matilda died sometime after Easter 1030 (when she was at the imperial court) and before January 1034, when Emperor Conrad II issued a diploma at the intervention of his wife Gisela, commemorating her death.[15] She is often said to have died on 29 July 1032. She was buried in Worms Cathedral. After Matilda's death, her young daughters (Beatrice and Sophie) from her second marriage to Frederick were adopted by her sister, Empress Gisela.[16]

Issue

With her first husband, Conrad, Matilda had three children:

- Conrad II, Duke of Carinthia

- Bishop Bruno of Würzburg

- Gisela (?), who married Count Gerhard of Metz, whose brother was Bruno of Toul (later Pope Gregory V).

With her second husband, Frederick, Matilda had three children:[17]

If she was married to Esico of Ballenstedt, Matilda had two further children:

- Adalbert II, Count of Ballenstedt

- Adelaide of Ballenstadt, wife of Thiemo of Schraplau.

Notes

- Goez, Beatrix, p. 11.

- Keller, ‘Schwäbische Herzöge als Thronbewerber,’ esp. pp. 135ff.

- Boshoff, Die Salier, pp. 23f.

- There is some debate about how closely Matilda and Conrad were related to one another. For contrasting views, see Wolfram, Konrad II, pp. 42, 54; and Wolf, 'Königskandidatur,' pp. 83-86

- Corbet, Autour de Burchard de Worms, pp. 120ff.

- Boshoff, Die Salier, pp. 25f.

- Boshoff, Die Salier, p. 29

- Goez, Beatrix, p. 11

- Mohr, Geschichte, pp. 77-80.

- Erkens, Konrad II, p. 37.

- An English translation of this letter is accessible at: Epistolae: Medieval Women's Latin Letters Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- The manuscript is now in Düsseldorf University Library, but the miniature has been lost and only copies remain. See Kürbis, "Die Epistola Mathildis Suevae an Mieszko II"

- Goez, Beatrix, p. 11.

- Annalista Saxo, a.1026, p. 363.

- Die Urkunden Konrads II, no. 204, p. 277

- Goez, Beatrix, p. 12

- Goez, Beatrix, p. 11

References

- E. Freise, Mathilde von Schwaben in Neue Deutsche Biographie 16 (1990), pp. 375f. (in German)

- H. Wolfram, Kaiser Konrad II, 990-1039. Kaiser dreier Reiche (Munich, 2000).

- F-R. Erkens, Konrad II. (um 990-1039). Herrschaft und Reich des ersten Salierkaisers (1998).

- H. Keller, ‘Schwäbische Herzöge als Thronbewerber: Hermann II. (1002), Rudolf von Rheinfelden (1077), Friedrich von Staufen (1125), Zur Entwicklung von Reichsidee und Fürstenverantwortung, Wahlverständnis und Wahlverfahren im 11. und 12. Jahrhundert,’ Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins 131 (1983), 123–162

- P. Corbet, Autour de Burchard de Worms. L'église allemande et les interdits de parenté (IXème-XIIème siècle) (Frankfurt am Main, 2001).

- E. Boshoff, Die Salier (Stuttgart, 2008).

- Annalista Saxo, in Die Reichschronik des Annalista Saxo, ed. K. Nass, MGH SS 37 (Munich, 2006), accessible online at: Monumenta Germaniae Historica.

- Die Urkunden Konrads II, ed. H. Bresslau, MGH Diplomata 4 (Hannover and Leipzig, 1909), accessible online at: Monumenta Germaniae Historica

- B. Kürbis, "Die Epistola Mathildis Suevae an Mieszko II, in neuer Sicht, Ein Forschungsbericht," Frühmittelalterliche Studien, 23 (1989), 318-343.

- E. Goez, Beatrix von Canossa und Tuszien. Eine Untersuchung zur Geschichte des 11. Jahrhunderts (Sigmaringen, 1995).

- W. Mohr, Geschichte des Herzogtums Lothringen, vol. 1 (1974).

- A. Wolf, 'Königskandidatur und Königsverwandtschaft. Hermann von Schwaben als Prüfstein für das "Prinzip der freien Wahl", Deutsches Archiv 47 (1991), 45-118.

External links

- Epistolae: Medieval Women’s Latin Letters: Matilda of Swabia (Brief biography of Matilda, and an English translation of a letter written by her to Mieszko II of Poland)

- Medieval Lands Project

- Mathilde von Schwaben (in German)