Matthew Brettingham

Matthew Brettingham (1699 – 19 August 1769), sometimes called Matthew Brettingham the Elder, was an 18th-century Englishman who rose from humble origins to supervise the construction of Holkham Hall, and become one of the country's best-known architects of his generation. Much of his principal work has since been demolished, particularly his work in London, where he revolutionised the design of the grand townhouse. As a result, he is often overlooked today, remembered principally for his Palladian remodelling of numerous country houses, many of them situated in the East Anglia area of Britain. As Brettingham neared the pinnacle of his career, Palladianism began to fall out of fashion and neoclassicism was introduced, championed by the young Robert Adam.

Early life

Brettingham was born in 1699, the second son of Launcelot Brettingham (1664–1727), a bricklayer or stonemason from Norwich, the county town of Norfolk, England. He married Martha Bunn (c. 1697–1783) at St. Augustine's Church, Norwich, on 17 May 1721 and they had nine children together.[1]

His early life is little documented, and one of the earliest recorded references to him is in 1719, when he and his elder brother Robert were admitted to the city of Norwich as freemen bricklayers. A critic of Brettingham's at this time claimed that his work was so poor that it was not worth the nine shillings a week (£73 in 2021) he was paid as a craftsman bricklayer.[2] Whatever the quality of his bricklaying, he soon advanced himself and became a building contractor.[2]

Local contractor

During the early eighteenth century, a building contractor had far more responsibilities than the title suggests today. A contractor often designed, built, and oversaw all details of construction to completion. Architects, often called surveyors, were employed only for the grandest and largest of buildings. By 1730, Brettingham is referred to as a surveyor, working on more important structures than cottages and agricultural buildings. In 1731, it is recorded that he was paid £112 (£18,600 in 2021) for his work on Norwich Gaol.[3] From then, he appears to have worked regularly as the surveyor to the Justices (the contemporary local authority) on public buildings and bridges throughout the 1740s. Projects of his dating from this time include the remodelling of the Shirehouse in Norwich,[3] the construction of Lenwade Bridge over the river Wensum, repairs to Norwich Castle and Norwich Cathedral, as well as the rebuilding of much of St. Margaret's Church, King's Lynn, which had been severely damaged by the collapse of its spire in 1742.[1] His work on the Shirehouse, which was in the gothic style and showed a versatility of design rare for Brettingham, was to result in a protracted court case that was to rumble on through a large part of his life, with allegations of financial discrepancies.[4] In 1755, the case was eventually closed, and Brettingham was left several hundred pounds out of pocket—several tens of thousands, in present-day terms—and with a stain—if only a local one—on his character. Transcripts of the case suggest that it was Brettingham's brother Robert, to whom he had subcontracted and who was responsible for the flint stonework of the Shirehouse, who may have been the cause of the allegations.[5] Brettingham's brief flirtation with the Gothic style, in the words of Robin Lucas, indicates "the approach of an engineer rather than an antiquary" and is "now seen as outlandish".[1] The Shirehouse was demolished in 1822.[6]

Architect

In 1734, Brettingham had his first great opportunity, when two of the foremost Palladian architects of the day, William Kent and Lord Burlington, were collaboratively designing a grandiose Palladian country palace at Holkham in Norfolk for Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester. Brettingham was appointed Clerk of Works (sometimes referred to as executive architect),[7] at an annual salary of £50 (£8,100 per year in 2021). He retained the position until the Earl's death in 1759. The illustrious architects were mostly absent; indeed Burlington was more of an idealist than an architect, thus Brettingham and the patron Lord Leicester were left to work on the project together, with the practical Brettingham interpreting the architects' plans to Leicester's requirements. It was at Holkham that Brettingham first worked with the fashionable Palladian style, which was to be his trademark. Holkham was to be Brettingham's springboard to fame, as it was through his association with it that he came to the attention of other local patrons, and further work at Heydon and Honingham Hall established Brettingham as a local country-house architect.[8]

Brettingham was commissioned in 1742 to redesign Langley Hall, a mansion standing in its own parkland in South Norfolk. His design was very much in the Palladian style of Holkham, though much smaller: a large principal central block linked to two flanking secondary wings by short corridors. The corner towers, while similar to those later designed by Brettingham at Euston Hall, were the work of a later owner and architect. The neoclassical entrance lodges were a later addition, by Sir John Soane. In 1743, Brettingham began work on the construction of Hanworth Hall, Norfolk, also in the Palladian style, with a five-bay facade of brick with the centre three bays projected with a pediment.

In 1745, Brettingham designed Gunton Hall in Norfolk for Sir William Harbord, three years after the former house on the site was gutted by fire. The new house of brick had a principal facade like that of Hanworth Hall, however, this larger house was seven bays deep, and had a large service wing on its western side. His commissions began to come from further afield: Goodwood in Sussex and Marble Hill, Twickenham.[1][9]

In 1750, now well-known, the architect received an important commission to remodel Euston Hall in East Anglia, the Suffolk country seat of the influential 2nd Duke of Grafton.[9] The original house, built circa 1666 in the French style, was built around a central court with large pavilions at each corner. While keeping the original layout, Brettingham formalised the fenestration and imposed a more classically severe order whereby the pavilions were transformed to towers in the Palladian fashion (similar to those of Inigo Jones's at Wilton House). The pavilions' domes were replaced by low pyramid roofs similar to those at Holkham. Brettingham also created the large service courtyard at Euston that now acts as the entrance court to the mansion, which today is only a fraction of its former size.[10]

The Euston commission seems to have brought Brettingham firmly to the notice of other wealthy patrons. In 1751, he began work for the Earl of Egremont at Petworth House, Sussex. He continued work intermittently at Petworth for the next twelve years, including designing a new picture gallery from 1754. Over the same period his country-house work included alterations at Moor Park, Hertfordshire; Wortley Hall, Yorkshire; Wakefield Lodge, Northamptonshire; and Benacre House, Suffolk.[1][9]

London townhouses

From 1747, Brettingham operated from London as well as Norwich. This period marks a turning point in his career, as he was now no longer designing country houses and farm buildings just for the local aristocrats and the Norfolk gentry, but for the greater aristocracy based in London.[11]

One of Brettingham's greatest solo commissions came when he was asked to design a town house for the 9th Duke of Norfolk in St. James's Square, London.[12] Completed in 1756, the exterior of this mansion was similar to those of many of the great palazzi in Italian cities: bland and featureless, the piano nobile distinguishable only by its tall pedimented windows. This arrangement, devoid of pilasters and a pediment giving prominence to the central bays at roof height, was initially too severe for the English taste, even by the fashionable Palladian standards of the day. Early critics declared the design "insipid".[13]

_House_Pall_Mall.jpg.webp)

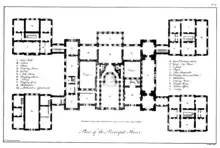

However, the interior design of Norfolk House was to define the London town house for the next century.[13] The floor plan was based on an adaptation of one of the secondary wings he had built at Holkham Hall.[14] A circuit of reception rooms centred on a grand staircase, with the staircase hall replacing the Italian traditional inner courtyard or two-storey hall. This arrangement of salons allowed guests at large parties to circulate, having been received at the head of the staircase, without doubling back on arriving guests. The second advantage was that while each room had access to the next, it also had access to the central stairs, thus allowing only one or two rooms to be used at a time for smaller functions. Previously, guests in London houses had had to reach the principal salon through a long enfilade of minor reception rooms. In this square and compact way, Brettingham came close to recreating the layout of an original Palladian Villa. He transformed what Andrea Palladio had conceived as a country retreat into a London mansion appropriate for the lifestyle of the British aristocracy, with its reversal of the usual Italian domestic pattern of a large palazzo in town, and a smaller villa in the country. As happened so often in Brettingham's career, Robert Adam later developed this design concept further, and was credited with its success. However, Brettingham's plan for Norfolk House was to serve as the prototype for many London mansions over the next few decades.

Brettingham's additional work in London included two more houses in St. James's Square: No. 5 for the 2nd Earl of Strafford and No. 13 for the 1st Lord Ravensworth.[15] Lord Egremont, for whom Brettingham was working in the country at Petworth, gave Brettingham another opportunity to design a grandiose London mansion—the Egremont family's town house. Begun in 1759, this Palladian palace, known at the time as Egremont House, or more modestly as 94 Piccadilly, is one of the few great London town houses still standing. It later came to be known as Cambridge House and was the home of Lord Palmerston, and then of the Naval & Military Club; as of October 2007, it is in the process of conversion into a luxury hotel.[16]

Kedleston Hall

Sir Nathaniel Curzon, later 1st Baron Scarsdale, commissioned Brettingham in 1759 to design a great country house. Thirty years before a prospective design for a new Kedleston Hall had been drawn up by James Gibbs, one of the leading architects of the day,[18] but Curzon wanted his new house to match the style and taste of Holkham. Lord Leicester, Holkham's owner and Brettingham's employer, was a particular hero of Curzon's.[19] Curzon was a Tory from a very old Derbyshire family, and he wished to create a showpiece to rival the nearby Chatsworth House owned by the Whig Duke of Devonshire, whose family were relative newcomers in the county, having arrived little more than two hundred years earlier.[20] However, the Duke of Devonshire's influence, wealth, and title were far superior to Curzon's, and Curzon was unable to complete his house or to match the Devonshires' influence (William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, had been Prime Minister in the 1750s). This commission might have been the ultimate accolade Brettingham was seeking, to recreate Holkham but this time with full credit. Kedleston Hall was designed by Brettingham on a plan by Palladio for the unbuilt Villa Mocenigo.[19] The design by Brettingham, similar to that of Holkham Hall, was for a massive principal central block flanked by four secondary wings, each a miniature country house, themselves linked by quadrant corridors.[21] From the outset of the project, Curzon seems to have presented Brettingham with rivals. In 1759, while Brettingham was still supervising the construction of the initial phase, the northeast family block, Curzon employed architect James Paine, the most notable architect of the day, to supervise the kitchen block and quadrants.[22] Paine also went on to supervise the construction of Brettingham's great north front. However, this was a critical moment for architecture in England. Palladianism was being challenged by a new taste for neoclassical designs, one exponent of which was Robert Adam.[22] Curzon had met Adam as early as 1758, and had been impressed by the young architect newly returned from Rome. He employed Adam to design some garden pavilions for the new Kedleston.[23] So impressed was Curzon by Adam's work that by April 1760 he had put Adam in sole charge of the design of the new mansion, replacing both Brettingham and Paine.[23] Adam completed the north facade of the mansion much as Brettingham had designed it, only altering Brettingham's intended portico.[17] The basic layout of the house remained loyal to Brettingham's original plan, although only two of the proposed four secondary wings were executed.

Brettingham moved on to other projects. In the 1760s, he was approached by his most illustrious patron, the Duke of York (brother of King George III), to design one of the greatest mansions in Pall Mall, namely York House. The rectangular mansion that Brettingham designed was built in the Palladian style on two principal floors, with the state rooms as at Norfolk House, arranged in a circuit around the central staircase hall. The house was a mere pastiche of Norfolk House, but for Brettingham it had the kudos of a royal occupant.

Legacy

Its royal occupant may very well have made York House the pinnacle of Brettingham's career. Built during the 1760s, it was one of his last grand houses. His last country-house commission was at Packington Hall, Warwickshire. In 1761, he published his plans of Holkham Hall, calling himself the architect, which led critics, including Horace Walpole, to decry him as a purloiner of Kent's designs.[1][24] Brettingham died in 1769 at his house outside St. Augustine's Gate, Norwich, and was buried in the aisle of the parish church. Throughout his long career, Brettingham did much to popularise the Palladian movement.[25] His clients included a Royal Duke and at least twenty-one assorted peers and peeresses. He is not a household name today largely because his provincial work was heavily influenced by Kent and Burlington, and unlike his contemporary Giacomo Leoni he did not develop, or was not given the opportunity to develop, a strong personal stamp to his work on country houses. Ultimately, he and many of his contemporary architects were eclipsed by the designs of Robert Adam. Adam remodelled Brettingham's York House in 1780 and, in addition to Kedleston Hall, went on to replace James Paine as architect at Nostell Priory, Alnwick Castle, and Syon House. In spite of this, Adam and Paine remained great friends; Brettingham's relationships with his fellow architects are unrecorded.

Brettingham's principal contribution to architecture is perhaps the design of the grand town house, unremarkable for its exterior but with a circulating plan for reception rooms suitable for entertaining within on a forgotten scale of lavishness. Many of these anachronistic palaces are now long demolished[26] or have been transformed for other uses and are inaccessible for public viewing. Hence, what little remains in London of his work is unknown to the general public. Of Brettingham's work, only the buildings he remodelled have survived, and for this reason Brettingham now tends to be thought of as an "improver" rather than an architect of country houses.

There is no evidence that Brettingham ever formally studied architecture or travelled abroad. Reports of him making two trips to Continental Europe,[27] are the result of confusion with his son, Matthew Brettingham the Younger.[2] That he enjoyed success in his own lifetime is beyond doubt—Robert Adam calculated that when Brettingham sent his son, Matthew, on the Grand Tour (1747), he went with a sum of money in his pocket of around £15,000 (£2.43 million in 2021), an enormous amount at the time.[11] However, part of this sum was probably used to acquire the statuary in Italy (documented as supplied by Matthew Brettingham the Younger) for the nearly completed Holkham Hall. Matthew Brettingham the Younger wrote that his father "considered the building of Holkham as the great work of his life".[28] While the design of that great monumental house, which still stands, cannot truly be accredited to him, it is the building for which Brettingham is best remembered.

Notes

- Lucas

- Howell James, p.345

- Howell James, p.346

- Howell James, p.348 onwards

- Howell James, p.349 and Colvin, p.155

- Colvin, p.157

- Nicolson, p.247

- Colvin, pp.154 and 156

- Colvin, p.156

- Euston Hall The History of Euston Hall Archived 2012-02-02 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 7 March 2008.

- Howell James, p.350

- Girouard, p.196

- Girouard, p.197

- Girouard, p.195

- Sheppard, pp.99–103 and 136–139

- City of Westminster (25 October 2007) Minutes of Planning Applications Sub-Committee 3 Archived 2008-04-10 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 10 March 2008.

- The National Trust, p.10

- The National Trust, p.7

- Jackson-Stops, p.94

- Jackson-Stops, p.92

- Harling, p.126

- Jackson-Stops, p.95

- The National Trust, p.9

- Wilson, pp.175–176

- Centre for Urban History, School of Historical Studies, University of Leicester (25 June 2007) Architecture: The Classical Style Archived 2007-10-10 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 7 March 2008.

- York House was demolished between 1908 and 1912; Norfolk House was demolished in 1938. Source: Colvin, pp.156–157

- Burnett

- Colvin, p.154

References

- Burnet, G. W. (1886). "Brettingham, Matthew". In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 6. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 287–288.

- Colvin, Howard (1995). A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840. Third edition. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06091-2

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English Country House. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02273-5.

- Harling, Robert (1969). Historic Houses. Conde Nast Publications.

- Howell James, D. E. (1964). "Matthew Brettingham and the County of Norfolk", Norfolk Archaeology 33, Part III.

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase (1990). The Country House in Perspective. Pavilion Books. ISBN 1-85145-383-0.

- Lucas, Robin (September 2004; online edition January 2008). "Brettingham, Matthew, the elder (1699–1769)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved on 6 March 2008. (Subscription required)

- Nicolson, Nigel (1965). Great Houses of Britain. George Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. ISBN 0-600-01651-X.

- The National Trust (1988; repr. 1997). Kedleston Hall.

- Sheppard, F. H. W. (ed.) (1960). Survey of London. Volume 29: St. James Westminster, Part 1. English Heritage.

- Wilson, Michael I. (1984) William Kent. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-9983-5.