Melittobia australica

Melittobia australica is a species of chalcid wasp from the family Eulophidae which is a gregarious ecto-parasitoid of acuealate Hymenoptera.

| Melittobia australica | |

|---|---|

| |

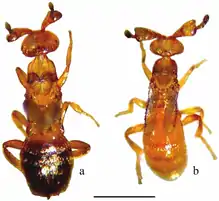

| male Melittobia acasta (right) male Melittobia australica (left) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Eulophidae |

| Subfamily: | Tetrastichinae |

| Genus: | Melittobia |

| Species: | M. australica |

| Binomial name | |

| Melittobia australica Girault, 1912 | |

Description

Melittobia australica is a small wasp between 1.1 and 1.4 mm in length but has the typical wasp body plan of a head, thorax, abdomen body structure with the "wasp waist". It is sexually dimorphic with males is normally being larger than females, males are 1.2 to 1.4 mm in length while females are 1.1 to 1.3 mm. Males also have a with a wider head and smaller wings are smaller and their antennal scape is significantly broader. The colour difference is that the males are also a honey brown whereas the females are coloured dark brown.[1]

There are at least two morphs of females in M. australica which differ in the sixe of the abdomen, the size of the eyes and the extent of wing development. The "crawler" morph have a normal abdomen, small eyes and underdeveloped wings. The "flier" and possibly the "jumper" morphs have larger eyes and wings and a smaller abdomen. The "crawlers" remain within the host nest for the whole of their life cycle while the other morphs disperse as adults.[1]

Distribution

Melittobia australica was first described by the American entomologist Alexandre Arsène Girault in 1912 from Australia but it has since been recorded from North America, Central America, northern South America, the Caribbean, Africa, eastern Asia, Europe (Sicily) and New Zealand.[2][3] Some authorities believe that it is indigenous to Australia but that human commercial activity has allowed it to spread and become cosmopolitan.[1]

Habitat

In Australia Melittobia australica was original reared from the nest of the sphecid wasp Pison spinolae by Girault[3] and rainforest was the original habitat.[1]

Biology

Melittobia australica is a parasitoid and its primary hosts are solitary bees and wasps. Its life cycle starts with the female finding the nest of a suitable host where the progeny are in the prepupal stage. The female feeds on the prepupa, she punctures it with the ovipositor and feeds on the exuded body fluids, using the proteins in the ingested fluid for ovogenesis.[4] She lays 10–50 eggs per day under the pupal covering of the host. Fertilised eggs develop into female wasps and unfertilised eggs into males, a behaviour known as arrhenotoky. The eggs are normally laid on a single host within the nest and many females may lay eggs on the same host which can be completely covered in larval M. australica of different ages which emerge from the eggs a few days after oviposition. The larvae feed on the tissue of the host and their development of the fames into the differing morphs is determined by the density of larvae feeding on the host. Where there is a low density of larvae the females will mainly be "crawlers" whereas intermediate densities will result in "jumpers" or and high densities of larvae will cause mostly "fliers" to develop.[1] Where the host larvae are small the female may lay her eggs on more than one host.[4]

Male M. australica produce a very powerful pheromone to attract females. As they have been laid on the same host at the same time the males mature at the same time as their sisters and often mate with them. If males encounter other males they will fight, often resulting in the death of the losing male.[1] It has also been observed that the first male to emerge will often decapitate any other males either before the merge or immediately after emergence and I another observation the first male to emerge stopped the development of the other males by touching them with his antennae.[4] There are up to 50 females per male and it is not known why the males fight when there are so many females. Once the male finds a receptive female they start a courtship ritual which involves tactile, chemical and auditory signals including the release of pheromone from the abdomen, the raising and lowering of the male's legs and the male rubbing the female with his antennae which also have a large gland which may produce pheromones too. The males hold the female's head in their mandibles, just below the ocelli and maintain antennal contact throughout the ritual which usually lasts 15 minutes.[4] The ritual is followed by mating which fertilises the females eggs. The female then finds a new host, in the same nest if she is a "crawler" or in a new nest if she is a "jumper" or a "flier" and begins to lay eggs on the new host. Each female lays a mean of 10.9 eggs on a host and these take 2–3 days to hatch, the larvae take 20–30 days to develop into adults, depending on conditions, and begin the life cycle again. Under laboratory conditions females live up to 9 days as adults and the total livespan is between 31 and 37 days.[1] The female will normally mate only once while the males are polygynous. If no males are present or an inseminated female has used up all of the sperm from mating she may lay a few unfertilised eggs to produce males, often mating with her own son.[4]

M. australica is a gregarious ectoparasitoid and when the female oviposits on a host she releases a pheromone which attracts other females to that site. All of the progeny resulting form a mating are laid on the same host and they develop together, consuming the host's tissues and eventually killing it. The newly mature females move to the original oviposition site and release a pheromone which induces nearby females to co-operate in forming a group, called a "chewing circle", which chews through the cuticle of the host allowing the adult wasps to escape. The adults, however are solitary and after mating the males die and the females move to a new host.[1]

Females seem to detect the cells of the hosts by chemical means and once a nest is detected the female remains in its vicinity but they do not appear to be attracted to the cells, rather they are "chemically arrested".[1] Female M. australica have been observed excavating access holes through the mud walls of the nests of Pison sp. with their mandibles, just one hole per cell was excavated and several females were observed working on each hole. Only a single female at a time worked on the digging, each taking turns.[4] Adult females are responsive to light, phototaxis, with the crawlers being negatively phototaxic and the fliers positively phototaxic, i.e. attracted to light, so that they leave the host nest after mating.[1] The females can delay feeding and egg laying for several weeks until the host reaches an appropriate developmental stage, they will even wait in empty cells until the host uses them.[4]

M. australica is totally dependent on the host wasps for food, the females feed on the host before oviposition and the larvae consume the host. Adult males probably do not feed.[4] The primary hosts are solitary wasps and bees but it will also parasitise inquilines of other insect orders where these are present in the host's nest. Bumblebees have also been found to be hosts of this wasp. Where populations of M. australica are high it can have a noticeable effect on the populations of host species and many of the host species have evolved defences against M. australica including nest location, chemical defences, physical barriers and defensive behaviours. Where M. autralica is common there can be a high mortality of its host species, which are often pollinators, and so M. australica parasitism can lead to an inhibition in the reproductive and dispersal capabilities of many plants. There is very little information about predators and parasites of M. australica, although an egg hyperparasitoid, Anagrus putnamii, has been recorded it has not been confirmed that it was using M. australica as its host.[1] In addition, there have been observations of parasitic mites which feed on larvae of the sphecid wasp Sceliphron spp. competing with M. australica larvae and even feeding upon them.[4]

Hosts

The first recorded host of Melittoboa australica was Pison spinolae;[3] however, the primary hosts are leaf cutting bees Megachile spp, mason wasps and mud dauber wasps but it is wide-ranging in its choice of hosts. There are no indigenous social wasps in Australia but in New Zealand and North America it has been recorded in the nests of Vespula species, as well as nests of Polistes, Bombus and honeybees Apis mellifera.[5][4] The bombyliid fly Anthrax angularis and the ichneumonid Stenarella victoriae are parasites in the nests of Sceliphron spp. and have been recorded as being viable hosts for M. australica. In addition, M. australica were found on dipteran puparia found in the nests of Sceliphron which are thought to be parasites on the spiders stocked in empty cells by the wasps.[4]

References

- Andrew Wood (2012). Heidi Liere; Barry O'Connor; Rachelle Sterling (eds.). "Melittobia australica". Animal Diversity Web. Regents of the University of Michigan. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Jorge M González; Julio A. Genaro; Robert W. Matthews (2004). "Species of Melittobia (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) established in Bahamas, Costa Rica, Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and Trinidad". Florida Entomologist. 87 (4): 619–620. doi:10.1653/0015-4040(2004)087[0619:somhee]2.0.co;2.

- Antonino Cusumano; Jorge M. González; Stefano Colazza; S. Bradleigh Vinson (2012). "First report of Melittobia australica Girault in Europe and new record of M. acasta (Walker) for Italy". ZooKeys (181): 45–51. doi:10.3897/zookeys.181.2752. PMC 3332020. PMID 22539910.

- Edward C. Dahms (1984). "A review of the biology of species within the the [sic] genus Melittobia (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) with interpretations and additions using observations on Melittobia australica" (PDF). Memoirs of the Queensland Museum. 21 (2): 337–360.

- R. P. Macfarlane; R. L. Palma (1987). "The first record for Melittobia australica Girault in New Zealand and new host records for Melittobia (Eulophidae)". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 14 (3): 423–425. doi:10.1080/03014223.1987.10423014.