Mesenchytraeus solifugus

Mesenchytraeus solifugus is a species of Oligochaete worms commonly called ice worms that inhabits coastal glaciers in the North Western portion of North America. M. solifugus is dark brown and grows to about 15 mm long and 0.5 mm wide. They have a high population density and are relatively common in their area. The ice worms are also very sensitive to temperature and can only survive from approximately -7 °C to 5 °C.

| Mesenchytraeus solifugus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Clitellata |

| Order: | Haplotaxida |

| Family: | Enchytraeidae |

| Genus: | Mesenchytraeus |

| Species: | M. solifugus |

| Binomial name | |

| Mesenchytraeus solifugus (Emery, 1898) | |

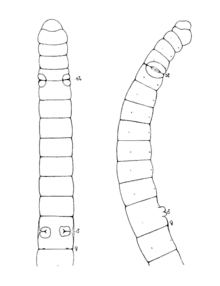

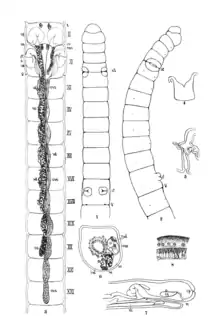

Description

Adult ice worms measure around 15 mm in length and about 0.5 mm in diameter. Their fluid and flexible body are able to squeeze through air holes and tiny crevasses in ice.

It is believed that the ice worm has a lifespan of five to ten years.

Ice worms have heavy pigment, absorbing all colours or reflecting dark brown; however, they burrow into glaciers to avoid strong sunlight. Carlo Emery named the species solifugus in 1898, meaning "fleeing from the sun".

Distribution and habitat

Ice worms populate coastal glaciers in North America from Alaska to northern Washington state.

The worms appear on the surface in high density; researchers have counted between 30 and 300 ice worms per square metre. On Byron glacier alone, researchers estimate the worms numbered around 30 million. The total number in all the coastal glaciers easily surpasses the entire human population.

Ecology

Mesenchytraeus solifugus have a very narrow acceptable temperature range. Ice worms freeze at around −6.8 °C (19.8 °F), and their bodies decompose after continuous exposure to temperatures above 5 °C (41 °F). This decomposition process, known as autolysis, occurs when the cells produce digestive enzymes and self-destruct. The body, figuratively, melts.

They are the only known worm to spend their entire life in temperatures near 0 C (32 °F). Even if other places are equally cold, ice worms never venture onto any other terrain. They eat the abundant snow algae and pollen carried by the wind.

In the summer, ice worms follow a diurnal cycle—at the first light in the morning, they sink into the glacier. A few hours before sunset, they poke out from the snow.

Ice worms can still be found in broad daylight. Many of them gather in glacial ponds or small streams. Scientists believe the water blocks out the sun's longer wavelengths which the worms avoid, and the freezing water provides the worms with a comfortable temperature.

In fast-flowing glacial streams, ice worms cling onto the icy surface. Researchers have observed the worms gyrate their head in the stream, possibly catching algae and pollen carried by the water. In still ponds, ice worms gather in bundles. Researchers speculate this has something to do with their reproduction. Ice worms do not graze in groups on the surface. The bonding in the still pond provides the rare opportunity for breeding.

Since in the winter the surface temperature on a glacier could reach −40 C (−40 °F), scientists doubt the worms follow the diurnal pattern. The worms most likely remain below the surface. The snowfall provides insulation and the temperatures below maintain a stable 0 C (32 °F). Ice worms can still find plenty of algae in the firn layer, the layer of packed snow in transition to ice. Scientists know little about the ice worm during the winter as the inaccessibility of glaciers prevents further study.

Medical uses

Researchers are now investigating what prevents the worm from freezing at 0 C (32 °F) and are looking at the evolutionary steps by which the ice worm diverged from other species. Understanding the ice worm's secret could help preserve vital organs for transplant, and could aid in the understanding of potential extraterrestrial life on cold planets, as well as species on Earth which survive in climates colder than previously thought possible.[1]

References

- Mauri, Pelto. "North Cascade Glacier Climate Project". Nichols College. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

Sources

- Hartzell, P. (2003). Glacial Ecology: North Cascades Glacier Macroinvertebrates. Retrieved on Oct. 21, 2005, from: https://web.archive.org/web/20051212000121/http://nichols.edu/departments/Glacier/bio/index.htm

- Pelto, M. S. (2003). Ice Worms (Mesenchytraeus solifugus) and Their Habitats on North Cascade Glaciers. A study by North Cascade Glacier Climate Project. Retrieved on Sept. 28, 2005, from https://web.archive.org/web/20090209012557/http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/iceworm.htm

- Shain, D. H., Carter M. R., Murray, K. P., Maleski, K. A., Smith, N. R., McBride, T. R., et al. (2000). Morphologic Characterization of the Ice Worm Mesenchytraeus solifugus. Journal of Morphology, 246, 192-197.

- Shain, D. H., Mason, T. A., Farrell, A. H., & Michalewicz, L. A. (2001). Distribution and behavior of ice worms (Mesenchytraeus solifugus) in south-central Alaska. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 79, 10, 1813-1821.