Monitory democracy

Monitory democracy is a phase of democracy characterised by instruments of public monitoring and scrutinising of government power.[1] It began following the events of the Second World War. The theory was coined by Australian Professor John Keane.

Monitory institutions refer to 'watch-dog' and 'guide-dog' bodies which subject governments to a public mechanism of checks and balances.[2] Under the theory of monitory democracy these institutions extend the notions of representative democracy to "enfranchise many more citizens voices"[2] in the political process. The ability to publicly monitor government power enabled through these institutions has the effect of changing the political and geographic dynamics of existing representative democracies.[2]

According to Keane, monitory democracy adds to the democratic nature of political representation as it changes the notion from "'one person, one vote, one representative'"[2] and instead embodies the principles of "one person, many interests, many voices, multiple votes, multiple representatives"[2].[2]

Professor John Keane (political theorist)

John Keane | |

|---|---|

| Education | PhD, University of Toronto;

MA, University of Toronto BA, Hons (Adelaide) |

| Occupation | Professor of Politics and Director of the Sydney Democracy Network |

John Keane was born February 3, 1949 in South Australia.[3] He was educated at the University of Adelaide and then the University of Toronto where he completed a PhD.[4] His political writing was initially printed under the pseudonym, 'Erica Blair'.[3]

In 1989 he founded the Centre for the Study of Democracy (CSD) which is based in London at the University of Westminster.[5]

He currently writes a 'Democracy Field Notes' column for the website, The Conversation which is based in London, Melbourne and New York[3] and holds a seat in the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin, "Europe's biggest social science think tank".[6]

Keane theorised monitory democracy in his 2009 book 'The Life and Death of Democracy' and has expanded on the notion in his scholarly work since.

Development

Democracy is a system of government based on the "belief in freedom and equality between people... in which power is either held by elected representatives or directly by the people themselves"[7] Democracy is separated into distinct phases and has "no built-in historical guarantees".[1] Each phase of democracy coincides with a mode of communication; assembly democracy with spoken word, and representative democracy with print culture and mass broadcasting media.[8] Monitory democracy is defined by the emergence of extra-parliamentary 'watch dog' institutions which affect the dynamics of political representation within systems of representative democracy.[8]

Representative Democracy

Representative democracy is a system of democratic government where elected officials represent the citizen body in policy-making.[9] Thomas Hobbes developed the doctrine of representation describing it as a system government with the authorisation of the people to act in their behalf.[10] The notion of political representation emerged when the Athenian system of direct democracy began to limit the size of the citizenry.[10] When the citizenry became too large for people to physically meet and vote on issues, individuals began to select representatives to act on their behalf.[10] The first recognised representative assembly was the 17th century British Parliament.[10]

The creation of print culture and mass broadcasting media within representative democracy[8] enabled self organised pressure groups to emerge.[8] In response, political programs were designed specifically to "win the support of the people and to address voter concerns".[10]

There are currently two systems of representative democracy; parliamentary and presidential. The dynamics of representation operating within both these systems is impacted by monitory institutions which have "spread a culture of voting".[8]

Whilst Keane theorises monitory democracy as an expansion of representative democracy, stating, "just as modern representative democracies preserve the old custom of public assemblies of citizens, so monitory democracies keep alive and depend upon legislatures, political parties and elections...",[8] he indicates that monitory democracy "breaks the grip of the majority rule principle associated with representative democracy".[2]

Monitory Democracy

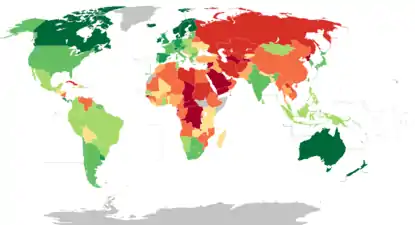

|

Most democratic (closest to 10) Least democratic (closest to 0) |

Monitory democracy relies on the assumption that democracies are "the most power sensitive polities ever known to humanity, democracies are capable of democratising themselves.".[1]

At the start of 1945 there were only 12 representative democracies in the world.[8] After the end of World War 2 the number of democracies began to rise again, increasing to 30 democratic regimes by 1959.[12] In 1991 when the Iron Curtain fell, there were 63 democracies in the world.[12] By 2017, 57% of countries, with populations of at least 500,000 people, were democracies.[13]

However, Keane states that the shift from representative to monitory democracy was the global awareness of the "dysfunctions and despotic potential of majority-rule democracy in representative form"[2] in tandem with the development of human rights recognition. This historical shift was facilitated by individual actors, collective groups, NGO's and the media.[2]

A monitor is a "device used for observing, checking, or keeping a continuous record of something."[14] to ensure it is carried out fairly.[14] Monitory institutions developed to democratise and scrutinise power.[2] Technological and communicatory shifts such as the creation of the Internet and the commercialisation of the media, led to an increased demand for factual and objective based power monitoring.[2]

Within monitory democracy public political participation is not exclusively achieved through representation.[8] Through means of unelected representatives "all fields of social and political life come to be publicly scrutinised"[8] where citizens can participate in all political areas such as health care and social welfare.[8] This impact of monitoring on representative democracy causes both national governments and international bodies (such as the United Nations) which represent the citizenry, to have increased accountability to them.[1]

Keane describes the political dynamics of monitory democracy as a system where, "elected and unelected representatives routinely strive to define and to determine who gets what, when and how; but the represented, taking advantage of various power-scrutinising devices, keep tabs on their representatives..."[2]

Monitory democracy is entrenched by the notion of communicative abundance.[2]

Communicative Abundance

Keane describes the concept of communicative abundance as the political idea of replacing the "scarcity"[15] of free press and public opinion with their abundance.

Technical restraints have been placed by governments on public access to information and expressions of opinion.[15] Keane states that within a democracy "power should be subject to ongoing public scrutiny"[15] with "more and better targeted media coverage to ensure that controversies about secret power are frequent and ongoing".[15] This "implied the creation of a common, accessible space in which matters of public importance could be considered freely and openly.".[15]

Communicative abundance involves the integration of media information within an affordable and accessible global network.[15] It is within this global network that monitory institutions operate under the "ethos of communicative abundance".[8] In doing so, communicative abundance represents the democratic intersection of the public and private sphere.[15]

Characteristics

Monitory democracy is characterised by institutions which have democratic power-checking effects.[2] These institutions are facilitated by communicative abundance.[15]

Monitory institutions "supplement the power-monitoring role of elected government representatives and judges".[8] These bodies operate based on different spatial scales[8] to enforce public standards and rules surrounding elected and unelected political representatives behaviour.[2] Monitory bodies will operate at the level of citizen's inputs to government or others can directly monitor government policy.[8] Some institutions provide the public with extra viewpoints and more information or lead to improved decision making within political institutions.[8] Others "specialise in providing public assessments of the quality of existing power-scrutinising mechanisms and the degree to which they fairly represent citizens' interests"[2] such as the Democratic Audit Network and Transparency International.[2]

A brief list of some monitory bodies include: advisory boards; focus groups; think tanks; democratic audits; consumer councils; online petitions; summits; websites; unofficial ballots; international criminal courts; global social forums; NGO's and watch-dog and guide-dog organisations.

Monitory institutions defy "descriptions of democracy as essentially a matter of elite-led party competition".[2] Keane states that monitory mechanisms confirm "James Madison's law of free government: no government can be considered free unless it is capable of governing a society that is itself capable of controlling the government.".[2]

Watch-dog Institutions

A watchdog institution is "a person or organisation responsible for making certain that companies obey particular standards and do not act illegally".[16]

Keane states that watch-dog institutions build upon the instruments of representative democracy such as "ombudsmen, royal commissions, public enquiries and independent auditors check".[2]

As a monitory mechanism, watchdog's demonstrate government's restricting their own arbitrary power through semi-independent organisations staffed by unelected representatives.[2] They act as a "group that watches the activities of a particular part of government in order to report illegal acts or problems" which violate public interest.[17]

In Australia in 1970–1980, media coverage of government corruption led to two royal commissions which resulted in the establishment of watch-dog institutions.[2] These were the Police Complaints Authority in 1985, the Queensland Criminal Justice Commission in 1990 and then the statutory Office of Integrity Commissioner.[2]

Guide-dog Institutions

Guide-dog institutions, such as electoral commissions and anti-corruption bodies, are neutral bodies who uphold and protect the level of democracy by 'guiding' policy and government behaviour.[2]

Non-Governmental Organisations

A non-governmental organisation (NGO) is a "voluntary group of individuals or organisations, usually not affiliated with any government that is formed to provide services or to advocate a public policy".[18] These organisations have humanitarian and cooperative objectives rather than commercial ones.[19] NGO's advocate for public interest through researched and publicised campaigns.[8]

Under monitory democracy NGO's provide the public with more information and actively lobby governments to alter policy.[8]

Organisations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International operate to routinely deal with human rights violations.[8] Keane states that these bodies answer the question of "who decides who 'the people' are",[8] advocating that "every human being is entitled to exercise their right to have rights, including the right to take advantage of communicative abundance by communicating freely with others as equals".[8]

Some accredited Australian NGO's include Action on Poverty, Oxfam Australia, Transform Aid International, World Vision Australia, WWF Australia, UNICEF Australia.[20]

Criticism

Keane's theory of monitory democracy outlined in 'The Life and Death of Democracy' (2009) has been critiqued by Christopher Hobson in a review of the book.[21] Hobson states that it is unclear "whether all the changes Keane identifies collectively constitute something coherent enough to be considered a new kind of democracy".[21] However, he states that monitory democracy provides a "valuable opening to begin discussing these issues, as part of considering the current shape and likely future of democracy".[21]

In another review of 'The Life and Death of Democracy' (2009), the Guardian referred to monitory democracy as an "ugly phrase".[22] They critique the theory as being "at best a partial description of what democracy is and what it needs to be.".[22] The article states that "monitory democracy can function only if it learns to co-exist with some of those democratic ideas that Keane is too quick to dismiss...".[22] Similarly, the Telegraph stated "What Keane himself fails to see is that the 'monitory democracy' he celebrates, while it may cut through some hierarchies of power, is busily constructing new hierarchies of its own: an activist elite; human rights judges who act beyond the reach of democratic politics; and so on.".[23]

References

- Keane, John (2009). "Bad Moons Little Dreams". The Life and Death of Democracy. London: Simon & Schuster. pp. ix–xxxiii. ISBN 9784622077435.

- Keane, John (2011), ‘Monitory democracy?’, in The Future of Representative Democracy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–235.

- "John Keane Biography". John Keane. 2010-12-06. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "John Keane". Sydney Democracy Network. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Centre for the Study of Democracy | University of Westminster, London". www.westminster.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "John Keane". Q&A. 2018-12-20. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "DEMOCRACY | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Keane John (2018), "Monitory Democracy", Power and Humility, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 103–132, doi:10.1017/9781108348997.004, ISBN 9781108348997

- Rank, Scott M. "What is a Representative Democracy?". www.historyonthenet.com. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Dehsen, Eleanora von (2013). The concise encyclopedia of democracy. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315063270. OCLC 1086516907.

- "Democracy Index 2018: Me too?". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- Roser, Max (2013-03-15). "Democracy". Our World in Data.

- "Despite global concerns about democracy, more than half of countries are democratic". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "monitor | Definition of monitor in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Keane, John (1999). "Public Life in the Era of Communicative Abundance". Canadian Journal of Communication. 24 (2). doi:10.22230/cjc.1999v24n2a1094. ISSN 1499-6642.

- "WATCHDOG | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- "GOVERNMENT WATCHDOG | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- "Nongovernmental organization". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Clarke, Paul Barry (2001). Encyclopedia of Democratic Thought. United States: Routledge. pp. 465–466. ISBN 9781138830028.

- "List of Australian accredited non-government organisations (NGOs)". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Hobson, Christopher (March 2010). "Governance, civil society and cultural politics". International Affairs. 86: 557–558 – via JSTOR.

- Runciman, David (2009-06-06). "Review: The Life and Death of Democracy by John Keane". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Malcolm, Noel (2009-05-31). "The Life and Death of Democracy by John Keane: review". ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2019-05-31.