Mountain Valley Pipeline

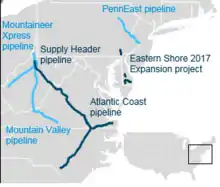

The Mountain Valley Pipeline is a joint venture project of Mountain Valley LLC partners and Equitrans LP,[1] which merged with a wholly owned subsidiary of Equitrans to form Equitrans Midstream Corporation in June 2020.[2] Their plan is to construct a pipeline that will transport natural gas. In total the project will consist of 304 miles of pipelines with an additional 8 miles as part of the Equitrans Expansion Project,[3] which will help to connect new and existing pipelines throughout the region.[1]

The evidence of a market demand and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Certificate policy requires at least 25 percent of the Mountain Valley Pipeline's capacity to deliver natural gas, be met by service contract agreements in order to justify the need for the project.[4] Mountain Valley was able to secure these service contracts allowing them to proceed with the proposed project. When the pipeline is completed it will have the ability to ship 2 million dekatherms (Dts) of natural gas per day for distribution, with a large quantity of that gas being produced from the Marcellus and Utica shale formations.[1]

Opposition was met during the initial request to obtain a certificate of convenience and necessity from the FERC.[4] Some of the issues raised by citizen groups include the right of eminent domain and the potential for negative impacts to the forests, waterways, and protected wildlife during construction.[5][6] The pipeline is also controversial due to the fact that it will cut across the Appalachian Trail.[7] A ruling by U.S. District Court Judge Elizabeth Dillon on January 31, 2018 granted the right of eminent domain to Mountain Valley in a disputed area but required current appraisals and bonds be set forth to compensate for any losses incurred by the land owners.[8] Currently the Mountain Valley Pipeline is in the preliminary phases of construction.

Local summaries from the Mountain Valley Pipeline Project website suggest it has the potential to bring in state and local tax revenue along with jobs and economic growth to Virginia and West Virginia,[9] a region where the impacts from a decline in the coal industry has caused a ripple effect that spans across the entire coal industry ecosystem.[10] The American Petroleum Institute claims that benefits from the pipeline could increased natural gas availability while providing a cleaner and cheaper alternative fuel source for American consumers.[11] There are concerns however from communities that will be impacted by the pipeline's construction and interest groups who want to preserve historical landmarks, forests, wildlife, waterways, and parks. Specific questions were raised regarding the need for the project and its purpose. Additional inquiries called in to question whether there were alternatives to avoid impacts to the forest among other things which were detailed in the Final Environmental Impact Statement, along with recommendations by the FERC to minimize the impacts on the environment.[3][4]

Project description

The MVP project is a natural gas pipeline from southern Virginia to northwestern West Virginia retrieving its supply from the Marcellus and Utica shale sites. It is expectedly to provide two billion cubic feet of firm capacity per day that can be used in commercial buildings in the Mid to the South Atlantic areas of the United States. The pipeline is regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission because it is an interstate obligation, and therefore must be overseen by the government, in accordance to the United States Natural Gas Act.[12]

The proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline natural gas pipeline will be owned and operated by Mountain Valley LLC, which is a joint venture between the energy provider Consolidated Edison, and various midstream partners, with EQT Midstream holding the most substantial stake.[1] This pipeline, as with all others, will be regulated by the United States Federal Energy Regulation Commission. The Natural Gas Act is the main piece of legislation that the FERC uses to govern natural gas pipelines. This act states that the FERC has the authority to regulate the transmission and sale of natural gas, approve or deny the construction or abandonment of natural gas facilities, and impose civil penalties if any of its specific provisions are not met.[13]

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) reviews applications for newly proposed interstate natural gas projects and regulates the energy markets of the nation. In October 2015, Mountain Valley filed for a formal FERC approval application for construction on the pipeline. In June, 2017 the Final Environmental Impact Statement issued by FERC.[14] After the pipeline is built, the authority of the pipeline gets turned over to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) where records of incidences are also kept.[15]

The MVP is overseen by the EQT Corporation, a utility company and drilling firm based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. EQT transports petroleum and natural gas and is one of the largest producers in the Appalachian Basin.[16]

The pipeline is projected to span approximately 303 miles,[12] and will cut across the Appalachian Trail near Peters Mountain Wilderness in Virginia.[7]

Opposition to the project

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy is the principal force opposing this pipeline. This organization has worked with Mountain Valley Pipeline officials in an effort to minimize mainly the environmental impacts along the Appalachian Trail, which is a major recreational area in not only Virginia and West Virginia, but many other Appalachian states as well. Though they have cooperated with the MVP officials, they have deemed many of the environmental effects unavoidable and extremely detrimental to the scenic beauty of the Appalachian Trail, and ultimately remain staunchly opposed to this pipeline.[17]

Additionally, many citizens of Virginia and West Virginia oppose this proposed pipeline. A group of concerned individuals have taken it upon themselves to "tree-sit" near Peters Mountain [18] in efforts to prevent logging crews from being able to effectively clear space for the construction of the pipeline,[19] while many others have voiced their opposition to this pipeline via news interviews, grassroots movements, and in one case, by a professor chaining herself to the pipeline.[20][21]

The head of the Jefferson National Forest was reassigned, allegedly due to heavy handed tactics involving the protest, which included running ATVs on a section of the Appalachian Trail,[22] and, according to Outside Magazine, blocking food and water supplies to protesters.[23]

Many landowners complain that they are kept up at night by construction, mainly because most of the land used to build the pipeline was taken from private landowners by eminent domain. In Virginia, bumper stickers are appearing on cars that read "No Pipeline". Many articles against the pipeline have been published in The Roanoke Times, and many protests have been organized.[24][25][26][27]

Mountain Valley Pipeline officials have repeatedly emphasized their dedication to the safe construction and operation of the pipeline.[28] According to the United States Department of Transportation, transport of natural gas through a pipeline is the safest delivery system for any form of energy.[28] The pipeline has determined to be providing 2 Bcf of natural gas daily to provide many markets and commercial building across the mid to south Atlantic areas.[29] Additionally, the pipeline would be regulated by the United States Natural Gas Act, federal and state level ordinances will dictate the construction and operation of the pipeline.

The Mountain Valley Pipeline has already been cited by government agencies for violations of Virginia's Stormwater Management Act, over problems with runoff from land clearance while installing the pipeline.[30]

Pipeline construction wound down for the season in October 2019, after "the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered the company to “cease immediately” all work on the interstate pipeline, at least until questions raised by the latest legal challenge are resolved."[31]

Controversies and impact

Landowners located along the pipeline project see the privately owned pipeline as a ‘government sanctioned land grab’, impacting not only the environment, but also the local economies of surrounding towns.[32] Recently, a Federal court put a hold on a required permit for construction of the pipeline in Monroe County, West Virginia.[33]

The environmental concerns of the pipeline include threats to the streams, rivers, and drinking water along the route. This can include the forests, endangered species, fish nurseries, and the public lands that surround the pipeline.[34] Water contamination has been one of the biggest concerns with the growth of this project, and there are concerns by some about the path of the pipeline, which cuts across sections of National Parks including the Jefferson National Forest in Virginia and West Virginia along with the Appalachian Trail.

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy has advocated against the creation of the pipeline,[17] arguing points including:

- The permanent damage of the scenic landscape of the Appalachian trail

- Concerns for nearby towns due to the lands being picked for the building of the pipeline are most susceptible to soil erosion, landslides, and natural gas leaks

- In order to push for the building of the MVP, the Forest Service lowered their standard for water quality, visual impacts, and destruction of the forest within the Jefferson National Forest Management Plan. There is a concern that due to this change, there could be an increase in private companies taking advantage of National Parks or forests

Proposed economic impacts are both positive and negative, including:

- Private landowners near the pipeline will lose property to the pipeline company. If the landowners are able to keep their land, the property value will decrease due to the pipeline's presence. Due to the process of eminent domain, the ability for the government to attain private land and make it public land, landowners could have their land taken and given to pipeline companies.[34]

- Consumers of the pipeline will have to pay additional taxes in their electrical bills to pay for the building of the Mountain Valley Pipeline

- Loss of ecosystem service value due to the destruction of the water purification and recreational benefits of the land[35]

Note that the statements above are from Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group.

Many economic gains have been argued by the Mountain Valley Pipeline project including:

- Increase in employment within the region, expected to gain 4,400 jobs within Virginia and 4,500 in West Virginia[36]

- Increase in direct spending on the areas impacted: $407 million directly in Virginia and $811 million directly in West Virginia[36]

- Potential of generating $35 million in tax revenues for the State of Virginia

- Positive tax revenues within Virginia, as the project has generate $35 million since 2015[37]

Timeline

October 2014

- Project first proposed. LLC began the voluntary pre-filing process with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)[38]

October 23, 2015

- LLC filed formal application within FERC[38]

October 13, 2017

- FERC issues LLC a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)[39]

December 2017

- Virginia State Water Control Board issues Water Quality Certification for the Mountain Valley Pipeline[40]

December 20, 2017

- The Bureau of Land Management issued a Rule of Decision granting LLC an operational right of way through the Jefferson National Forrest, and adopted the EIS[39]

December 22, 2017

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers verified that the Mountain Valley Pipeline project meets the criteria of the Nationwide Permit 12.[39]

January 31, 2018

- U.S. District Court Judge Elizabeth Dillon granted the right of eminent domain to Mountain Valley in a disputed area but required current appraisals and bonds be set forth to compensate for any losses incurred by the land owners.[8]

2018 (first quarter)

- Construction began, projected in-service date of the fourth quarter of 2019[38]

July 3, 2018

- The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reinstated their December 22 verification that the pipeline project complies with the Nationwide Permit 12, with several “special conditions”. One notable condition states that river crossings were to be constructed using dry open-cut construction in order to minimize environmental damage.[39]

July 27, 2018

- 4th Circuit Court annulled LLC’s right of way through federal land, which was originally granted by the Bureau of Land Management. It was annulled on the basis of failing to comply with the National Environmental Policy Act, the National Forest Management Act and the Mineral Leasing Act.[39]

October 2, 2018

- 4th Circuit court struck down Nationwide Permit 12, which was issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Huntington District. The court found that the permit overlooked a requirement by West Virginia regulators that pipeline stream crossings must be completed within 72 hours to limit environmental harm.[41]

November 27, 2018

- 4th Circuit Court of Appeals elaborated on their October 2 decision regarding the Nationwide Permit 12, concluding that West Virginia did not follow the federally mandated notice-and-comment procedures for waving special conditions part of the permit.[39]

December, 2018

- Virginia files suit against MVP for “violations of the commonwealth’s environmental laws and regulations at sites in Craig, Franklin, Giles, Montgomery, and Roanoke Counties.”[42]

March 1, 2019

- Virginia State Water Control Board decided they do not have the authority to revoke the water quality certification[40]

October 11, 2019

- 4th Circuit Appeals Court rescinds the Biological Opinion and Incidental Take Statement issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service[43]

- Virginia issued a statement forcing LLC to submit to court-ordered and court-supervised compliance with environmental protections, imposing additional layers of independent, third-party monitoring on the project, and requiring the payment of a significant $2.15 million civil penalty. This agreement between Virginia and LLC resolved the lawsuit Virginia filed against LLC in December 2018.[44]

October 15, 2019

- FERC ordered all work on MVP stop except stabilization and restoration activities[43]

June 2020

- MVP project is approximately 92% complete, in-service date revised to early 2021[45]

July 31, 2020

- Trinity Energy Services, a contractor of LLC, filed two lawsuits (one in PA, one in WV) claiming that LLC owes Trinity $104 million and demanding that LLC sell the pipeline at auction.[46]

August 11, 2020

- The North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resources denied LLC’s request for a 401 Water Quality Certification and Jordan Lake Riparian Buffer Authorization for the Southgate extension of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. The Division determined that the extension could lead to “unnecessary water quality impacts and disturbance of the environment in North Carolina.”[47]

- Secretary Michael S. Regan issued statement on the Department of Environmental Quality's decision, saying of the MVP, "This has always been an unnecessary project that poses unnecessary risks to our environment and given the uncertain future of the MVP Mainline, North Carolinians should not be exposed to the risk of another incomplete pipeline project."[48]

August 25, 2020

- Mountain Valley applied to FERC for a 2 year extension of Certificate for Public Convenience and Necessity (had expiration date in mid October). Certificate is required for interstate pipeline construction[49][50]

September 4, 2020

- Federal regulators ruled that the pipeline wouldn’t jeopardize any of the five endangered or threatened species known to live in its path,[49] reinstating the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Opinion and Incidental Take Statement.[50]

September 11, 2020

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reissued three permits (2 years after being invalidated by federal appeals court), approving a path across almost 1000 streams and wetlands[51]

September 22, 2020

- LLC requested that FERC lift the stop work order (issued October 11) by September 25.[52]

October 9, 2020

- FERC extended the Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity for the Mountain Valley Pipeline[53]

References

- "Overview". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "Company Profile - Equitrans Corporate Sustainability Report". csr.equitransmidstream.com. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ""Final Environmental Impact Statement". FERC Staff Issues Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Mountain Valley Project and Equitrans Expansion Project (CP16-10-000 and CP16-13-000)". ferc.gov. June 23, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "Order Issuing Certificates and Granting Abandonment Authority" (PDF). ferc.gov. October 13, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Schmalz, Arthur E. (February 6, 2018). "Virginia District Court Requires Pipeline Company to Obtain Appraisals Before Granting Preliminary Injunctions For Prejudgment Possession of Land". lexology.com. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Mall, Amy (February 26, 2018). "Northam Must Act to Protect Clean Water from Pipelines". nrdc.org. National Resource Defense Council.

- Gayter, Liam (February 21, 2017). "Thru-Hikers in the Blast Zone: Pipelines Will Intersect the Appalachian Trail". Blue Ridge Outdoors. Retrieved February 26, 2020.

- Hammack, Laurence (March 14, 2018). "Judge allows Mountain Valley Pipeline work to proceed on private property". roanoke.com. The Roanoke Times. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- "Local Summaries". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Mountain Valley Pipeline.

- "An Economic Analysis of the Appalachian Coal Industry Ecosystem" (PDF). arc.gov. Appalachian Regional Commission. January 2018.

- Tadeo, Michael (December 22, 2016). "VIRGINIA'S CONSUMERS AND ECONOMY WILL BENEFIT FROM THE MOUNTAIN VALLEY PIPELINE". api.org. American Petroleum Institute.

- "Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- "FERC Strategic Plan" (PDF).

- "Overview - Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". www.mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- Feridun, Karen (May 30, 2017). "What FERC Is And Why It Matters". Huffington Post.

- Waples, David A. (April 24, 2012). The Natural Gas Industry in Appalachia: A History from the First Discovery to the Tapping of the Marcellus Shale, 2d ed. McFarland. ISBN 9780786491544.

- "About Mountain Valley Pipeline". Appalachian Trail Conservancy. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Sturgeon, Jeff. "Mountain Valley Pipeline protesters continue tree-top vigil in W.Va". Roanoke Times. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- Schneider, Gregory S. (May 5, 2018). "Women sitting in trees to protest pipeline come down after judge threatens fines". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Why a Virginia Tech professor locked herself to pipeline construction equipment". Yale Climate Connections. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- "Why a Virginia Tech professor locked herself to pipeline construction equipment". Yale Climate Connections. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Hammack, Laurence (August 15, 2018). "Head of Jefferson National Forest temporarily reassigned as pipeline controversy continues". Roanoke Times. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Miles, Kathryn (April 25, 2018). "The Forest Service Is Arresting Protesters Along the AT". Outside Online. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Adams, Mason. "How a "bunch of badass queer anarchists" are teaming up with locals to block a pipeline through Appalachia". Mother Jones. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- laurence.hammack@roanoke.com 981-3239, Laurence Hammack. "Tree-sit protest of Mountain Valley Pipeline escalates, drawing police response". Roanoke Times. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- "Photos: Protests at the Mountain Valley Pipeline work site". The Franklin News Post. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- "Community Fights Construction of Mountain Valley Pipeline". Pulitzer Center. April 13, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- "Safety - Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- "Overview - Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- "Virginia DEQ issues violation for Mountain Valley Pipeline". whsv.com. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- Hammack, Laurence (October 20, 2019). "Work on Mountain Valley Pipeline is winding down". GoDanRiver.com. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Adams, Duncan (July 27, 2017). "Landowners along pipeline route sue FERC and Mountain Valley Pipeline". The Roanoke Times.

- Mishkin, Kate (June 21, 2018). "Federal court puts Mountain Valley Pipeline water crossing permit on hold". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- "10 Reasons to Stop Mtn. Valley & Atlantic Coast Pipelines". NRDC. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- Adams, Duncan (May 18, 2016). "Study backed by Mountain Valley Pipeline opponents suggests negative economic impacts for region". The Roanoke Times.

- "Economic Benefits - Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "New Study Projects Major Economic Benefits from Mountain Valley Pipeline for Southwest and Southside Virginia | EQT Media HQ". media.eqt.com. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- "Frequently Asked Questions | Mountain Valley Pipeline Project". www.mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Sierra Club v. USFS, No. 17-2399 (4th Cir. 2018)

- Dashiell, Joe. "State Water Control Board says it has no authority to revoke pipeline certification". wdbj7.com. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- lowkell. "BREAKING: U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals Vacates Nationwide Permit 12 for Entire Mountain Valley Pipeline". Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Vogelsong, Sarah. "Mountain Valley Pipeline agrees to pay Virginia $2.15 million for environmental violations". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Vogelsong, Sarah. "Federal commission orders work stopped on Mountain Valley Pipeline". Virginia Mercury. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "October 11, 2019 - MVP, LLC to Pay More Than $2 Million, Submit To Court-Ordered Compliance And Enhanced, Independent, Third-Party Environmental Monitoring". www.oag.state.va.us. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "Mountain Valley Pipeline Project |". www.mountainvalleypipeline.info. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "US Trinity Energy Services, LLC...W. Va Complaint". Scribd. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "State Denies Water Quality Certification for MVP Southgate Pipeline | NC DEQ". deq.nc.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "Statement from Secretary Regan on MVP Southgate Decision | NC DEQ". deq.nc.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "The 'last pipeline'? Mountain Valley Pipeline remains stalled as it seeks extension from federal regulators". Virginia Mercury. September 10, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "Time's up for the Mountain Valley Pipeline > Appalachian Voices". September 22, 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- laurence.hammack@roanoke.com 981-3239, Laurence Hammack. "Mountain Valley Pipeline regains permit to cross streams, wetlands". Roanoke Times. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Eggerding, Matthew, Assistant General Counsel of Mountain Valley Pipeline LLC. “Request to Resume Certain Construction Activities.” Received by Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, September 22, 2020. https://appvoices.org/images/uploads/2020/09/MVP-request-to-resume-construction-Sept-22-2020.pdf

- Callahan, Eddie. "FERC approves extension for Mountain Valley Pipeline". wdbj7.com. Retrieved October 31, 2020.