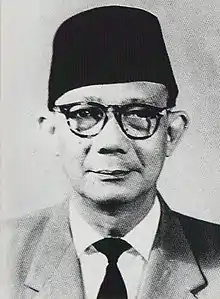

Muljadi Djojomartono

Muljadi Djojomartono (EYD: Mulyadi Joyomartono; 3 May 1898 – 23 October 1967) was an Indonesian politician and military officer who served as Coordinating Minister for People's Welfare between 1960–1966 and Minister of Social Affairs between 1957 and 1962 and briefly in 1966. Affiliated with the Islamic organization Muhammadiyah, he had originated in Surakarta and served as a battalion commander in the Defenders of the Homeland organization, which resulted in his participation during the Indonesian National Revolution as an officer in his hometown. He was appointed as a minister by Sukarno despite protestations from his political party and Muhammadiyah, which opposed Muljadi's accommodation of Sukarno's actions.

Muljadi Djojomartono | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinating Minister for People's Welfare | |

| In office 18 February 1960 – 28 March 1966[lower-alpha 1] | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Succeeded by | Adam Malik |

| Minister of Social Affairs | |

| In office 28 March 1966 – 25 July 1966 | |

| Preceded by | Rusiah Sardjono |

| Succeeded by | Albert Mangaratua Tambunan |

| In office 24 May 1957 – 6 March 1962[lower-alpha 2] | |

| President | Sukarno |

| Prime Minister | Djuanda Kartawidjaja |

| Preceded by | Johannes Leimena |

| Succeeded by | Rusiah Sardjono |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 3 May 1898 Surakarta, Dutch East Indies |

| Died | 23 October 1967 (aged 69) Jakarta, Indonesia |

Early life

Muljadi was born in Surakarta on 3 May 1898 and received education in Islamic institutions.[2]

Career

Pre-independence

For a time, he worked as an employee of the postal service.[3] Muljadi helped with the 1934 founding of a radio station in Surakarta, the SRI (Siaran Radio Indonesia), and he later became a well-known broadcaster on that station.[4] He was also active in various Islamic organizations prior to the outbreak of WW2.[2] During the Japanese occupation period, Muljadi joined the Japanese-controlled Defenders of the Homeland (PETA) military organization, where he was appointed a battalion commander in Surakarta, along with a number of other kyai who were also appointed to similar positions in PETA.[5]

Post-1945

During the Indonesian National Revolution, Muljadi became a leading figure within the pemuda movement in Surakarta, specifically the Barisan Banteng organization which he co-founded with Moewardi.[3][6] At one point, when a leader for the newly formed People's Security Agency was about to select a commander, Muljadi was nominated as one of six potential candidates, and in a public vote just two voted for him, with most voting for either Sudirman (who won) and Urip Sumohardjo.[7] Due to disputes between the central government and the local militants and authorities in Surakarta, Muljadi alongside other leading figures including Moewardi was briefly arrested in late May 1946. However, large-scale rallies coupled with an ultimatum from Barisan Banteng leader Sudiro who threatened to resign and hence leave the pemuda uncontrolled, resulted in Muljadi's release on 31 May.[8] He again was arrested by Dutch authorities after Operation Kraai in February 1949 when he refused to join the Dutch-formed "Islamic Council" for Surakarta.[9]

Muljadi was a member of the Central Java Regional People's Representative Council where he served as chairman as early as 1951,[10] and maintained his seat following the 1955 election.[11] He was also a member of Masyumi and Muhammadiyah's leadership committees.[11]

He was present as one of five Masyumi representatives at the presidential palace in April 1957 after Sukarno decreed a state of war the previous month in the aftermath of the Second Ali Sastroamidjojo Cabinet's resignation. As he approved of Sukarno's decision to issue said decree, he was later appointed a minister within the new Djuanda Cabinet.[12] Johannes Leimena was initially appointed as Minister of Social Affairs, but as he was promoted to Deputy First Minister, Muljadi was appointed to replace him on 24 May 1957.[13] While his approval was in line with some leaders within Masyumi, most of Masyumi and Muhammadiyah's leadership saw his actions as making the organization bow to pressure from Sukarno, which they saw as violating the constitution.[14] Shortly after his appointment, the Muhammadiyah plenary meeting held on 1-2 June 1957 in Yogyakarta removed him from the organization's leadership committee (in which he was vice-chairman) and expelled from the organization.[15]

After his appointment, Muljadi would serve as Minister for Social Affairs until the end of the First Working Cabinet, and then resumed his post with the title Junior Minister during the Second Working Cabinet, in which he also served as Minister for People's Welfare. In the Third Working Cabinet until the end of the Revised Dwikora Cabinet, he became Coordinating Minister for People's Welfare. He served one last ministerial term as Social Affairs Minister in the Second Revised Dwikora Cabinet.[1] Muljadi was well known to be hostile towards the Communist Party of Indonesia and an ardent supporter of Sukarno, to the point where he commented that if Sukarno had been born in 571 AD, he would have become an Islamic prophet.[lower-alpha 3][11]

He died on 23 October 1967 in his home in Jakarta due to a heart attack. He had been suffering from heart problems for some time before his death.[17]

Notes

- As Minister for People's Welfare between 18 February 1960 and 6 March 1962.[1]

- As Junior Minister for Social Affairs between 18 February 1960 and 6 March 1962.[1]

- From a speech at Gelora Bung Karno Stadium in commemoration of Mawlid, 6 August 1963.[16]

References

- Al-Hamdi, Ridho (2020). Paradigma Politik Muhammadiyah (in Indonesian). IRCISOD. p. 179. ISBN 978-623-7378-67-9.

- Asia Who's Who. 1960. p. 245.

- Amir, Muhammad. "Sejarah Berdirinya Muhammadiyah Kota Surakarta" (in Indonesian). Muhammadiyah. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Sejarah RRI Surakarta" (in Indonesian). Radio Republik Indonesia. p. 8. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- KH. Hasyim Asy'ari - Pengabdian Seorang Kyai Untuk Negeri (in Indonesian). Bahama Publisher. 2019. p. 89.

- Anderson, Benedict Richard O'Gorman (2006). Java in a Time of Revolution: Occupation and Resistance, 1944-1946. Equinox Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 978-979-3780-14-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nasution, Abdul Haris (1966). Sedjarah perdjuangan nasional dibidang bersendjata (in Indonesian). Mega Bookstore. p. 85.

- Anderson 2006, pp. 363-364.

- Sedjarah TNI-AD Kodam VII/Diponegoro (in Indonesian). Kodam VII/Diponegoro. 1968. p. 177.

- "Mangkunegara VII naar Europa". De Locomotief Samarangsch Handels- en Advertentieblad (in Dutch). 29 September 1951. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Maarif, Ahmad Syafii (1996). Islam dan politik: teori belah bambu, masa demokrasi terpimpin, 1959-1965 (in Indonesian). Gema Insani. p. 97. ISBN 978-979-561-428-9.

- Madinier, Remy (2015). Islam and Politics in Indonesia: The Masyumi Party between Democracy and Integralism. NUS Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-9971-69-843-0.

- Hitipeuw, Frans (1986). Dr. Johannes Leimena, karya dan pengabdiannya (in Indonesian). Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional. p. 177.

- "Cercaan Santun ala Buya Hamka". Republika Online (in Indonesian). 3 April 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- "Muhammadijah royeert minister Muljadi". Het nieuwsblad voor Sumatra (in Dutch). 4 June 1957. p. 3. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- Nakib, Firdaus Ahmad (1967). Dari pendjara ke medja hidjau (in Indonesian). Pustaka Nida. p. 181.

- "H. Muljadi Djojomartono Meninggal Dunia". Kompas (in Indonesian). 25 October 1967. p. 1. Retrieved 8 September 2020.