Mushabian culture

The Mushabian culture (alternately, Mushabi or Mushabaean) is an archaeological culture suggested to have originated among the Iberomaurusians in North Africa, though once thought to have originated in the Levant.[1][2]

Archaeologists' opinions

According to Ofer Bar-Yosef :

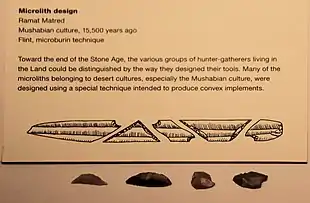

"A contemporary desertic entity was labeled "Mushabian," and was considered to be, on the basis of the technotypological features of its lithics, of North African origin. The fieldwork done in recent years in northern Sinai and the Negev has shown that the forms of the Mushabian microliths (mainly curved and arched backed bladelets) and the intensive use of the microburin technique was a trait foreign to previous Levantine industries, but instead is closer to the Iberomaurusian."[3]

According to Thomas Levy:

"The Mushabian is commonly considered to have originated in North Africa, largely on the basis of habitual of the microburin technique and general morphological similarities with some assemblages in Nubia(Phillips and Mintz 1977; Bar-Yosef and Vogel 1987."[1]

According to Eric Delson:

"A different industry, the Mushabian, is marked by steeply arched microliths and the frequent use of the microburin technique. The Mushabian is found exclusively in the arid interior southern Levant (e.g., Sinai), suggesting it could represent an arid-land adaptation. Some researchers have noted stylistic continuities between the Mushabian and the Ibero-Maurusian of North Africa, suggesting the Mushabian may represent a migration of African groups into the southern Levant."[2]

According to Deborah Olszewski:

- "At the time that Henry and Garrard analyzed and published the Tor Hamar assemblage, it was commonly believed that microburin technique appeared relatively late in the Levantine Epipaleolithic sequence, perhaps being derived from microburin technique in Egypt. Since then, however, several Jordanian sites have produced evidence of microburin technique well in advance of the latter part of the Epipaleolithic sequence. These include Wadi Uwaynid 18 and Wadi Uwaynid 14 in the Azraq region of Jordan, with radiocarbon dates between 19 800 and 18 400 uncal. BP, Tor at-Tareeq in the Wadi al-Hasa area of Jordan, with radiocarbon dates between 16 900 and 15 580 uncal. BP, and Tor Sageer, also in the Wadi al-Hasa area, with radiocarbon dates between 22 590 and 20 330 BP. This new evidence clearly documents the use of the microburin technique in the inland Levant during the earliest phases of the Epipaleolithic. Thus, its presence at sites such as Wadi Madamagh and Tor Hamar cannot necessarily be used to link these sites to the Mushabian Complex, a fact also noted by Byrd".[4]

According to Nigel Goring-Morris:

- "Another technological shift is reflected in the approach to microlith fabrication, when backed microliths replaced finely retouched types, sometimes using the microburin technique. The introduction and systematic use of this technique in the Levant (i.e., Nebekian, Nizzanan, and later the Mushabian, Ramonian, and Natufian) are an endemic phenomenon, originating east of the Rift Valley".[5]

Early migrations

The migration of farmers from the Middle East into Europe is believed to have significantly influenced the genetic profile of contemporary Europeans. The Natufian culture which existed about 12,000 years ago in the Levant, has been the subject of various archeological investigations as the Natufian culture is generally believed to be the source of the European Neolithic.

The Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert were formidable barriers to gene flow between Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe. But Europe was periodically accessible to Africans due to fluctuations in the size and climate of the Sahara. At the Strait of Gibraltar, Africa and Europe are separated by only 15 km of water. At the Suez, Eurasia is connected to Africa forming a single land mass. The Nile river valley, which runs from East Africa to the Mediterranean Sea served as a bidirectional corridor in the Sahara desert, that frequently connected people from Sub-Saharan Africa with the peoples of Eurasia.[6]

Mushabian-Kebaran merge

According to Bar-Yosef the Natufian culture emerged from the mixing of the Geometric Kebaran (indigenous to the Levant) and the Mushabian (most likely North African).[7][4] Modern analyses[8][9] comparing 24 craniofacial measurements reveal a predominantly cosmopolitan population within the pre-Neolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age Fertile Crescent,[8] supporting the view that a diverse population of peoples occupied this region during these time periods.[8] In particular, evidence demonstrates the presence of North European, Central European, Saharan and Sub-Saharan African presence within the region, especially among the Epipalaeolithic Natufians of Palestine.[8][10][11][12][13][14] These studies further argue that over time the Sub-Saharan influences would have been "diluted" out of the genetic picture due to interbreeding between Neolithic migrants from the Near East and Western Hunter Gatherer hunter-gatherers whom they came in contact with. However, a recent study showed that Natufians had no Sub-Saharan admixture.[15]

Ricaut et al. (2008)[16] associate the Sub-Saharan influences detected in the Natufian samples with the migration of E1b1b lineages from North Africa to the Levantα and then into Europe. Entering the late mesolithic Natufian culture, the E1b1b1a2 (E-V13) sub-clade has been associated with the spread of farming from the Middle East into Europe either during or just before the Neolithic transition. E1b1b1 lineages are found throughout Europe but are distributed along a South-to-North cline, with an E1b1b1a mode in the Balkans.[17][18]

- "Recently, it has been proposed that E3b originated in sub-Saharan Africa and expanded into the Near East and northern Africa at the end of the Pleistocene. E3b lineages would have then been introduced from the Near East into southern Europe by immigrant farmers, during the Neolithic expansion".''[18]

Also,

- "a Mesolithic population carrying Group III lineages with the M35/M215 mutation expanded northwards from sub-Saharan to North Africa and the Levant. The Levantine population of farmers that dispersed into Europe during and after the Neolithic carried these African Group III M35/M215 lineages, together with a cluster of Group VI lineages characterized by M172 and M201 mutations".[17]

Loosdrecht et al. (2018) consider that the Natufians arose from a population without SSA influences either in Morocco, Libya, or the Levant.

- "We speculate that the Natufian-related ancestral population may have been widespread across North Africa and the Near East, associated with microlithic backed bladelet technologies that started to spread out in this area by at least 25,000 yr B.P. [(10) and references therein]. However, given the absence of ancient genomic data from a similar time frame for this broader area, the epicenter of expansion, if any, for this ancestral population remains unknown. Although the oldest Iberomaurusian microlithic bladelet technologies are found earlier in the Maghreb than their equivalents in northeastern Africa (Cyrenaica) and the earliest Natufian in the Levant, the complex sub-Saharan ancestry in Taforalt makes our individuals an unlikely proxy for the ancestral population of later Natufians who do not harbor sub-Saharan ancestry. An epicenter in the Maghreb is plausible only if the sub-Saharan African admixture into Taforalt either postdated the expansion into the Levant orwas a locally confined phenomenon. Alternatively, placing the epicenter in Cyrenaica or the Levant requires an additional explanation for the observed archaeological chronology."[19]

Notes

- ^α Although a migration of people from Africa bringing E-M35 lineages into the Levant took place c. 14,700 years ago[20] it as yet cannot be linked with any of the Levantine cultures at the time (Hamran, Mushabian, Ramonian, Geometric Kebaran) or later (Natufian, Harifian, Khiamian) since all are known to have originated in the Levant.[4][5] Since a material culture cannot be connected with the E-M78 immigrants into the Levant it is likely they were assimilated into the various Levantine cultures beginning with the Ramonian culture, which was present in the Sinai 14,700 years ago. This migration coincided with the population overflow in the Sinai and Negev that caused the Geometric Kebarans to fall back to the Mediterranean core area which in turn caused them to develop the Natufian culture as a result of the population increase in the Mediterranean park forest.[21]

References

- Levy, Thomas (1995-01-01). Arch Of Society. A&C Black. p. 161. ISBN 9780718513887.

- Delson, Eric; Tattersall, Ian; Couvering, John Van; Brooks, Alison S. (2004-11-23). Encyclopedia of Human Evolution and Prehistory: Second Edition. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 9781135582272.

- Annual Review of Anthropology. Annual Reviews Incorporated. 1972. pp. 121. ISBN 9780824319090.

- Olszewski, D.I. Issues in the Levantine Epipaleolithic : The Madamaghan, Nebekian and Qalkhan (Levant Epipaleolithic). Paléorient, 2006, Vol. 32 No. 1, p. 19-26.

- Goring-Morris, Nigel et al. 2009.The Dynamics of Pleistocene and Early Holocene Settlement Patterns in the Levant: An Overview. In Transitions in Prehistory: Essays in Honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef (eds) John J. Shea and Daniel E. Lieberman. Oxbow Books, 2009. ISBN 9781842173404.

- Krings M, Salem AE, Bauer K, et al. (April 1999). "mtDNA analysis of Nile River Valley populations: A genetic corridor or a barrier to migration?". American Journal of Human Genetics. 64 (4): 1166–76. doi:10.1086/302314. PMC 1377841. PMID 10090902.

- Delson, Eric; Tattersall, Ian; Couvering, John Van; Brooks, Alison S. (2004-11-23). Encyclopedia of Human Evolution and Prehistory: Second Edition. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 9781135582289.

- Brace, C. L.; Seguchi, N; Quintyn, CB; Fox, SC; Nelson, AR; Manolis, SK; Qifeng, P (January 2006). "The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 103 (1): 242–247. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102. PMC 1325007. PMID 16371462.

- Ricaut, F. X.; Waelkens, M. (August 2008). "Cranial Discrete Traits in a Byzantine Population and Eastern Mediterranean Population Movements". Human Biology. 80 (5): 535–564. doi:10.3378/1534-6617-80.5.535. PMID 19341322. S2CID 25142338.

- Barker, G (2002). "Transitions to farming and pastoralism in North Africa". In Bellwood, P; Renfrew, C (eds.). Examining the Farming/Language Dispersal Hypothesis. McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. pp. 151–161. ISBN 978-1-902937-20-5.

- Bar-Yosef, O. (1987). "Pleistocene connexions between Africa and Southwest Asia: an archaeological perspective". The African Archaeological Review. 5: 29–38. doi:10.1007/BF01117080. S2CID 132865471.

- Kislev ME, Hartmann A, Bar-Yosef O (2006). "Early domesticated fig in the Jordan Valley". Science. 312 (5778): 1372–1374. doi:10.1126/science.1125910. PMID 16741119. S2CID 42150441.

- Lancaster, Andrew (2009). "Y Haplogroups, Archaeological Cultures and Language Families: a Review of the Multidisciplinary Comparisons using the case of E-M35" (PDF). Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 5 (1): 35. ISSN 1557-3796.

- Findings include remains of food items carried to the Levant from Africa —— Parthenocarpic figs (please refer to prior reference: Kislev, Hartmann, Bar-Yosef, Nature, 2006) and Nile shellfish (please refer to Natufian culture#Long distance exchange).

- Lazaridis, Iosif; Nadel, Dani; Rollefson, Gary; Merrett, Deborah C.; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Fernandes, Daniel; Novak, Mario; Gamarra, Beatriz (2016-06-16). "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers". bioRxiv: Page 6. doi:10.1101/059311.

- Ricaut FX, Waelkens M (October 2008). "Cranial discrete traits in a Byzantine population and eastern Mediterranean population movements". Human Biology. 80 (5): 535–64. doi:10.3378/1534-6617-80.5.535. PMID 19341322. S2CID 25142338.

- Underhill PA, Passarino G, Lin AA, et al. (January 2001). "The phylogeography of Y chromosome binary haplotypes and the origins of modern human populations" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 65 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6510043.x. PMID 11415522. S2CID 9441236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-15.

- Cruciani F, La Fratta R, Santolamazza P, et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1014–22. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

- Loosdrecht, Marieke van de; Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Humphrey, Louise; Posth, Cosimo; Barton, Nick; Aximu-Petri, Ayinuer; Nickel, Birgit; Nagel, Sarah; Talbi, El Hassan (2018-03-15). "Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations". Science. 360 (6388): 548–552. doi:10.1126/science.aar8380. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29545507.

- Cruciani, Fulvio et al 2004. Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74:1014–1022, 2004.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer and Anna Belfer-Cohen. The Origins of Sedentism and Farming Communities in the Levant. Journal of World Prehistory 4:447-498.