Naïve cynicism

Naïve cynicism is a philosophy of mind, cognitive bias and form of psychological egoism that occurs when people naïvely expect more egocentric bias in others than actually is the case.

The term was formally proposed by Justin Kruger and Thomas Gilovich and has been studied across a wide range of contexts including: negotiations,[1] group-membership,[2] marriage,[2] economics,[3] government policy[4] and more.

History

Early examples from social psychology (1949)

The idea that 'people naïvely believe they see things objectively and others do not' has been acknowledged for quite some time in the field of social psychology. For example, while studying social cognition, Solomon Asch and Gustav Ichheiser wrote in 1949:

- "[W]e tend to resolve our perplexity arising out of the experience that other people see the world differently than we see it ourselves by declaring that those others, in consequence of some basic intellectual and moral defect, are unable to see the things “as they really are” and to react to them “in a normal way.” We thus imply, of course, that things are in fact as we see them and that our ways are the normal ways."[5]

Formal laboratory experimentation (1999)

The formal proposal of naïve cynicism came from Kruger and Gilovich's 1999 study called "'Naive cynicism' in everyday theories of responsibility assessment: On biased assumptions of bias".[2]

Theory

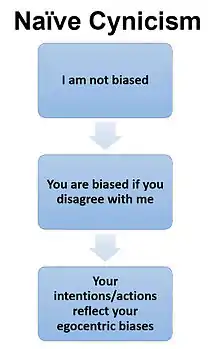

The theory of naïve cynicism can be described as:

- I am not biased.

- You are biased if you disagree with me.

- Your intentions/actions reflect your underlying egocentric biases.

A counter to naïve realism

As with naïve realism, the theory of naïve cynicism hinges on the acceptance of the following three beliefs:

Naïve cynicism can be thought of as the counter to naïve realism, which is the belief that an individual perceives the social world objectively while others perceive it subjectively.[6]

It is important to discern that naïve cynicism is related to the notion that others have an egocentric bias that motivates them to do things for their own self-interest rather than for altruistic reasons.

Both of these theories, however, relate to the extent that adults credit or discredit the beliefs or statements of others.[7]

Relating to psychological egoism

Psychological egoism is the belief that humans are always motivated by self-interest.

In a related quote, Joel Feinberg, in his 1958 paper "Psychological Egoism", embraces a similar critique by drawing attention to the infinite regress of psychological egoism:

"All men desire only satisfaction."

"Satisfaction of what?"

"Satisfaction of their desires."

"Their desires for what?"

"Their desires for satisfaction."

"Satisfaction of what?"

"Their desires."

"For what?"

"For satisfaction"—etc., ad infinitum.[8]

The circular reasoning evidenced by Feinberg's quote exemplifies how this view can be thought of as the need for others to have incessant personal desires and satisfaction.

Definition

There are several ways to define naïve cynicism such as:

- The tendency to expect others’ judgments will have a motivational bias and therefore will be biased in the direction of their self-interest.[6]

- Expecting that others are motivationally biased when determining responsibility for positive and negative outcomes.

- The propensity to believe that others are prone to committing the fundamental attribution error, false consensus effect or self-enhancement bias.[6]

- When our assumptions of others' biases exceed their actual biases.

Examples

Cold War

The American reaction to a Russian SALT treaty during the Cold War is one well-known example of naïve cynicism in history. Political leaders negotiating on behalf of the United States discredited the offer simply because it was proposed by the Russian side.[1][9]

Former U.S. congressman Floyd Spence indicates the use of naïve cynicism in this quote:

- "I have had a philosophy for some time in regard to SALT, and it goes like this: the Russians will not accept a SALT treaty that is not in their best interest, and it seems to me that if it is their best interests, it can‘t be in our best interest."[9]

Marketplace

Consumers exhibit naïve cynicism toward commercial companies and advertisers through suspicion and awareness toward marketing strategies used by such companies.[10]

Politics

The public displays naïve cynicism toward governments and political leaders through distrust.[11]

Workplace

Employees of large business organizations frequently exhibit naïve cynicism toward their companies and executives in the workplace through employee cynicism or organizational cynicism.[12]

Decision-making behavior

Naïve cynicism can be exemplified in some decision-making behaviors such as:

- Negotiations / Bargaining

- Economic games

- The Acquiring a Company Problem

- The Monty Hall Problem

- Competitive betting

Other possible real-world examples

- Overestimating the influence of financial compensation on people’s willingness to give blood.

- If another person tends to favor himself when interpreting uncertain information, someone exhibiting naïve cynicism would believe the other person is intentionally misleading them for their own advantage.[13]

- Assuming that group membership has a large influence on beliefs and attitudes.[14]

- If an individual of one political party makes an interpretation or a statement in favor of his own party and thus in accord with his self-interest, other adults discount his statement (especially if they belong to an opposing party).

- Likewise, if that individual makes a statement against his own self-interest, adults are more likely to believe him.[15]

- If an individual of one political party makes an interpretation or a statement in favor of his own party and thus in accord with his self-interest, other adults discount his statement (especially if they belong to an opposing party).

Resulting negative outcomes

Naïve cynicism can contribute to several negative outcomes including:

- Over-thinking the actions of others.

- Making negative attributions about others' motivations without sufficient cause.

- Missing opportunities that greater trust might capture.

Reducing

The major strategy to attenuate naïve cynicism in individuals has been shown by:

- Viewing the other person as part of one's in-group or acknowledging they are working in cooperation.

As a result of applying this strategy, happier married couples were less likely to exhibit cynical beliefs about each other’s judgments.[2]

Individuals are especially likely to exhibit naïve cynicism when the other person has a vested interest in the judgment at hand. However, if the other person is dispassionate about the judgment at hand, the individual will be less likely to engage in naïve cynicism and think the other person will see things the way they do.[2]

Psychological contexts

Naïve cynicism may play a major role in these psychology-related contexts:

Groups

In one series of classic experiments by Kruger and Gilovich, groups including video game players, darts players and debaters were asked how often they were responsible for good or bad events relative to their partner. Participants evenly apportioned themselves for both good and bad events, but expected their partner to claim more responsibility for good events than bad events (egocentric bias) than they actually did.[2]

Marriage

In the same study conducted by Kruger and Gilovich, married couples were also examined and ultimately exhibited the same type of naïve cynicism about their marriage partner as did partners of dart players, video game players and debaters.[2]

Altruism

Naïve cynicism has been exemplified in the context of altruism. Explanations of selfless human behavior have been described in terms of individuals seeking personal advantage as opposed to absolute altruism.[16]

For example, naïve cynicism would explain the act of an individual donating money or items to charity as a way of self-enhancement rather than for altruistic purposes.

Dispositionists vs. situationists

Dispositionists are described as individuals who believe people's actions are conditioned by some internal factor, such as beliefs, values, personality traits or abilities, rather than the situation they find themselves in.

Situationists, in contrast, are described as individuals who believe people's actions are conditioned by external factors outside of one's control.

Dispositionists exemplify naïve cynicism while situationists do not.[17] Therefore, situationist attributions are often thought to be more accurate than dispositionist attributions. However, dispositionist attributions are commonly believed to be the dominant schema because situationist attributions tend to be dismissed or attacked.

In a direct quote from Benforado and Hanson's paper titled "Naïve Cynicism: Maintaining False Perceptions in Policy Debates", the situationist and dispositionist are described as:

- "...the naïve cynic is a self-aware—even proud—critic.

- She speaks what she believes to be the truth, though it may require disparaging her opponents.

- She senses that she is delving below the surface of the complex arguments of the situationists; she “sees,” for example, the financial interest, the prejudice, or the distorting zealotry that motivates the situationist.

- She “sees” the bias and self-interest in those who would disagree—while maintaining an affirming view of herself as objective and other-regarding.

- The naïve cynic, then, is a dispositionist who cynically dispositionalizes the situationist. :She protects fundamentally flawed attributions by attacking the sources of potentially more accurate attributions.

- The naïve cynic understands (though rarely consciously) that the best defense is a good offense."[4]

Examples of differences

- Dispositionists might explain bankruptcy as the largely self-inflicted result of personal laziness and/or imprudence.

- Situationists might explain bankruptcy as frequently caused by more complicated external forces, such as divorce or the medical and other costs of unanticipated illness.[18]

Applied contexts

In addition to purely psychological contexts, naïve cynicism may play a major role in several applied contexts such as:

Negotiations

Naïve cynicism has been studied extensively in several contexts of negotiating such as bargaining tactics, specifically in the sense that too much naïve cynicism can be costly.[1]

Negotiators displaying naïve cynicism rely on distributive and competitive strategies and focus on gaining concessions rather than on problem-solving. This can be detrimental and lead to reduced information exchange, information concealment, coordination, cooperation and quality of information revealed.[1]

Reducing naïve cynicism in negotiations

The following strategies have been identified as ways to reduce naïve cynicism in the context of negotiations:

Perspective taking

It has been shown that individuals who focus more on the perspectives of their opponents were more successful in experimental laboratory negotiations.

Taking another person's perspective produced better predictions of opponents' goals and biases, though it is noted that many individuals lack the ability to properly change perspectives. These incapable individuals tend to view their opponents as passive and can be prone to ignore valuable information disseminated during negotiations.[19]

Negotiator role reversal is believed to be an important focus of training for individuals to be less inclined to use naïve cynicism during negotiations. This process involves having each negotiator verbally consider their opponents perspective prior to making any judgements.[20]

Communication

It has been shown when communication between opponents in negotiations is strong, negotiators are more likely to avoid stalemates.[21]

Negotiators who exhibit strong communication skills tend to believe integrity should be reciprocally displayed by both sides and thus regard open communication as a positive aspect in negotiations. Those negotiators high in communication skills also tend to view deadlocks as a negative event and will avoid reaching an impasse in order to reach an agreement.[21]

Feedback

Despite attempts to reduce errors of naïve cynicism in laboratory studies with error-related feedback, errors still persisted even after many trials and strong feedback.[22]

Governmental policy debates

In relation to governmental policy debates, it is hypothesized that naïve cynicism fosters a distrust of other political parties and entities. Naïve cynicism is thought to be a critical contributor for why certain legal policies succeed and others fail.

For example, naïve cynicism is thought to be a factor contributing to the existence of detention centers such as Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo Bay, Bagram Air Base and more.[4]

Related biases

Biases including the following have been argued to be caused at least partially by naïve cynicism:

See also

References

- Tsay, Chia-Jung; Shu, Lisa L.; Bazerman, Max H. (2011). "Naïveté and Cynicism in Negotiations and Other Competitive Contexts". The Academy of Management Annals. 5 (1): 495–518. doi:10.1080/19416520.2011.587283.

- Kruger, Justin; Gilovich, Thomas (1999). "'Naive cynicism' in everyday theories of responsibility assessment: On biased assumptions of bias". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 76 (5): 743–753. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.743.

- Heath, Joseph (2006). "Business ethics without stakeholders" (PDF). Business Ethics Quarterly. 16 (4): 533–557. doi:10.5840/beq200616448.

- Benforado, Adam; Hanson, Jon (2008). "Naïve Cynicism: Maintaining False Perceptions in Policy Debates". Emory Law Journal. 57 (3): 535. SSRN 1106690.

- Ichheiser, Gustav (1949). "Misunderstandings in Human Relations: A Study in False Social Perception". American Journal of Sociology. 55 (2).

- Baumeister, Roy; Vohs, Kathleen, eds. (August 29, 2007). Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 601. ISBN 978-1-4129-1670-7.

- Miller, Dale (December 1999). "The norm of self-interest". American Psychologist. 54 (12): 1053–1060. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.12.1053. PMID 15332526.

- Feinberg, Joel. "Psychological Egoism." In Reason & Responsibility: Readings in Some Basic Problems of Philosophy, edited by Joel Feinberg and Russ Shafer-Landau, 520-532. California: Thomson Wadsworth, 2008.

- Ross, Lee; Stillinger, Constance (1991). "Barriers to Conflict Resolution". Negotiation Journal. 7 (4): 389–404. doi:10.1111/j.1571-9979.1991.tb00634.x.

- Friest, Marian; Wright, Peter (June 1994). "The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts". Journal of Consumer Research. 21 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1086/209380. JSTOR 2489738.

- Jamieson, Kathleen (January 1997). "Setting the Record Straight Do Ad Watches Help or Hurt?". The International Journal of Press/Politics. 2 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1177/1081180x97002001003.

- Mirvis, Phillip; Kanter, Donald (Fall 1989). "Combatting cynicism in the workplace". National Productivity Review. 8 (4): 377–394. doi:10.1002/npr.4040080406.

- Tenbrunsel, Anne (May 1999). "Trust as an Obstacle in Environmental-Economic Disputes". American Behavioral Scientist. 42 (8): 1350–1367. doi:10.1177/00027649921954895.

- Miller, Dale; Ratner, Rebecca (1998). "The disparity between the actual and assumed power of self-interest". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.53. PMID 9457775.

- Murukutla, N; Armor, DA (2003). "Illusions of objectivity in the dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir". Yale University.

- Boyd, Robert; Peter, Richerson (2005). "Solving the puzzle of human cooperation". Evolution and Culture: 105–132. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.6027.

- Chiu, Chi-yue; Hong, Ying-yi (1997). "Lay Dispositionism and Implicit Theories of Personality" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 73 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.19. PMID 9216077.

- Norton, Helen. "Situationism v. Dispositionism". article.

- Neale, Margaret; Bazerman, Max (April 1983). "The Role of Perspective-Taking Ability in Negotiating under Different Forms of Arbitration". ILR Review. 36 (3): 378–388. doi:10.1177/001979398303600304.

- Pruitt, Dean (1991). Strategy in negotiation. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass.

- Bazerman, Max (1998). Can negotiators outperform game theory. pp. 79–99.

- Grosskopf, Brit; Bereby-Meyer, Yoella; Bazerman, Max (2007). "On the robustness of the winner's curse phenomenon". Theory and Decision. 63 (4): 389–418. doi:10.1007/s11238-007-9034-6.