Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya[1] (Russian: Надежда Константиновна Крупская, IPA: [nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə]; 26 February [O.S. 14 February] 1869 – 27 February 1939)[2] was a Russian revolutionary and the wife of Vladimir Lenin.

Nadezhda Krupskaya | |

|---|---|

Надежда Крупская | |

_2019-11-22.jpg.webp) Nadezhda Krupskaya, c. 1890s | |

| Deputy Minister of Education in the Government of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 1929 – 27 February 1939 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya 26 February [O.S. 14 February] 1869 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | 27 February 1939 (aged 70) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) (1903–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1939) |

| Spouse(s) | |

Krupskaya was born in Saint Petersburg to an aristocratic family that had descended into poverty, and she developed strong views about improving the lot of the poor. She embraced Marxism and met Lenin at a Marxist discussion group in 1894. Both were arrested in 1896 for revolutionary activities and after Lenin was exiled to Siberia, Krupskaya was allowed to join him in 1898 on the condition that they marry. The two settled in Munich and then London after their exile, before briefly returning to Russia to take part in the failed Revolution of 1905.

Following the 1917 Revolution, Krupskaya was at the forefront of the political scene, becoming a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee in 1924. From 1922 to 1925, she was aligned with Joseph Stalin, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev against Trotsky's Left Opposition, though she later fell out with Stalin. She was deputy education commissar from 1929 to 1939, with strong influence over the Soviet educational system, including the development of Soviet librarianship.

Early life

Nadezhda Krupskaya was born to an upper-class but impoverished family. Her father, Konstantin Ignat'evich Krupski (1838–1883), was a Russian military officer and a nobleman of the Russian Empire who had been orphaned in 1847 at the age of nine. He was educated and given a commission as an infantry officer in the Russian Army.[3] Just before leaving for his assignment in Poland, he married Krupskaya's mother. After six years of service, Krupski lost favour with his supervisors and was charged with "un-Russian activities." He may have been suspected of being involved with revolutionaries. Following this time he worked in factories or wherever he could find work. Just before his death, he was recommissioned as an officer.[4]

Krupskaya's mother, Elizaveta Vasilyevna Tistrova (1843–1915), was the daughter of landless Russian nobles. Elizaveta's parents died when she was young and she was enrolled in the Bestuzhev Courses, the highest formal education available to women in Russia at the time. After earning her degree, Elizaveta worked as a governess for noble families until she married Krupski.[5]

Having parents who were well educated and of aristocratic descent, combined with first-hand experience of lower-class working conditions, probably led to the formation of many of Krupskaya's ideological beliefs. "From her very childhood Krupskaya was inspired with the spirit of protest against the ugly life around her."[6]

One of Krupskaya's friends from gymnasium, Ariadne Tyrkova, described her as "a tall, quiet girl, who did not flirt with the boys, moved and thought with deliberation, and had already formed strong convictions . . . She was one of those who are forever committed, once they have been possessed by their thoughts and feelings . . ."[7] She briefly attended two different secondary schools before finding the perfect fit with Prince A. A. Obolensky's Female Gymnasium, "a distinguished private girls' secondary school in Petersburg." This education was probably more liberal than most other gymnasiums since it was noted that some of the staff were former revolutionaries.[8]

After her father's death, Krupskaya and her mother gave lessons as a source of income. Krupskaya had expressed an interest in entering the education field from a young age.[9] She was particularly drawn to Leo Tolstoy's theories on education, which were fluid instead of structured. They focused on the personal development of each individual student and centred on the importance of the teacher–student relationship.[10]

This led Krupskaya to study many of Tolstoy's works, including his theories of reformation. These were peaceful, law-abiding ideas, which focused on people abstaining from unneeded luxuries and being self-dependent instead of hiring someone else to tend their house, etc. Tolstoy made a lasting impression on Krupskaya; it was said that she had "a special contempt for stylish clothes and comfort."[11] She was always modest in dress, as were her furnishings in her home and office.

As a devoted, lifelong student, Krupskaya began to participate in several discussion circles. These groups were formed to study and discuss particular topics for the benefit of everyone involved. It was later, in one of these circles, that Krupskaya was first introduced to the theories of Marx. This piqued her interest as a potential way of making life better for her people[12] and she began an in-depth study of Marxist philosophy. This was difficult since books on the subject had been banned by the Russian government, meaning that revolutionaries collected them and kept them in underground libraries.

Married life

Krupskaya first met Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (later known as Vladimir Lenin) in 1894[13] at a similar discussion group. She was impressed by his speeches but not his personality, at least not at first. It is hard to know very much of the courtship between Lenin and Krupskaya as neither party spoke often of personal matters.[14]

In October 1896, several months after Lenin was arrested, Krupskaya was also arrested. After some time, Lenin was sentenced to exile in Siberia. They had very little communication while in prison but before leaving for Siberia, Lenin wrote a "secret note" to Krupskaya that was delivered by her mother. It suggested that she could be permitted to join him in Siberia if she told people she was his fiancée. At that time, Krupskaya was still awaiting sentencing in Siberia. In 1898,[13] Krupskaya was permitted to accompany Lenin but only if they were married as soon as she arrived.[15]

In her memoirs, Krupskaya notes "with him even such a job as translation was a labour of love".[16] Her relationship with Lenin was more professional than marital, but she remained loyal, never once considering divorce.

It is believed Krupskaya suffered from Graves' disease,[17] an illness affecting the thyroid gland in the neck which causes the eyes to bulge and the neck to tighten. It can also disrupt the menstrual cycle, which may explain why Lenin and Krupskaya never had children.[3]

Upon his release, Lenin went off to Europe and settled in Munich. Upon her release Krupskaya joined him (1901). After she arrived, the couple moved to London.

Political career

Krupskaya's political life was active: she was anything but a mere functionary of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from 1903.

Leon Trotsky, who was working closely with Lenin and Krupskaya from 1902 to 1903, writes in his autobiography ("My Life", 1930) of the central importance of Krupskaya in the day-to-day work of the RSDLP and its newspaper, Iskra. "The secretary of the editorial board [of Iskra] was [Lenin's] wife [...] She was at the very center of all the organization work; she received comrades when they arrived, instructed them when they left, established connections, supplied secret addresses, wrote letters, and coded and decoded correspondence. In her room there was always a smell of burned paper from the secret letters she heated over the fire to read..."[18]

Krupskaya became secretary of the Central Committee in 1905; she returned to Russia the same year, but left again after the failed revolution of 1905 and worked as a teacher in France for a couple of years.

After the October Revolution in 1917, she was appointed deputy to Anatoliy Lunacharskiy, the People's Commissar for Education, where she took charge of Vneshkol'nyi Otdel the Adult Education Division. She became chair of the education committee in 1920 and was the deputy education commissar (government minister) from 1929 to 1939.

Krupskaya was instrumental in the foundation of the Soviet educational system itself, including the censorship within it. She was also fundamental in the development of Soviet librarianship.

Krupskaya became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1924, a member of its control commission in 1927, a member of the Supreme Soviet in 1931 and an honorary citizen in 1931.

After the death of Vladimir Lenin in January 1924, Krupskaya grew closer to the political positions of Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev in Party debates. Factions that would later form throughout the 1920s included Trotsky-led Left Opposition, the Stalin-led "Centre", and the Bukharin-led Right Opposition. From 1922 to 1925, Zinoviev and Kamenev were in a triumvirate alliance with Stalin's Centre, against Trotsky's Left Opposition. In 1925, Krupskaya attacked Leon Trotsky in a polemic reply to Trotsky's tract Lessons of October. In it, she stated that "Marxist analysis was never Comrade Trotsky's strong point."[19]

In relation to the debate around Socialism in one country versus Permanent Revolution, she asserted that Trotsky "under-estimates the role played by the peasantry." Furthermore, she held that Trotsky had misinterpreted the revolutionary situation in post-World War I Germany. During both the Party Conference and Party Congress in 1925, she supported Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev against Joseph Stalin, as the troika of recent years broke up.[19] In 1926, Krupskaya, Zinoviev and Kamenev went into an alliance with Trotsky's Left Opposition, to form the United Opposition, against Stalin. Krupskaya was quoted by Trotsky's son Leon Sedov in his book The Red Book: On the Moscow Trial as saying "Lenin was only saved from prison by his death".[20] With state pressure growing to expel the United Opposition, Krupskaya eventually voted for the expulsion of the United Opposition from the Communist Party in December 1927, a position demanded by the Right Opposition and Stalin's Centre.[19]

In 1936, she defended restrictions on abortion passed by the Soviet government in that year, arguing that they were part of a consistent policy pursued since 1920 to do away with the reasons to have an abortion.[21]

Krupskaya wrote a memoir of her life with Lenin, translated in 1930 as Memories of Lenin and in 1959 as Reminiscences of Lenin.[22] The book gives the most detailed account of Lenin's life before his coming to power and ends in 1919.

In 1922, a conflict emerged among Bolshevik leadership over the status of Georgia and under what terms it would form political union with the RSFSR. This conflict came to be known as the Georgian Affair, and took on a personal as well as a political dimension among high-ranking members of the Bolshevik party, including Stalin, Trotsky, and Lenin.

According to Poskrebyshev and Kaganovich, she was poisoned by order by Stalin during celebration of her seventieth birthday.[23][24]

Soviet education and libraries

Before the revolution, Krupskaya worked for five years as an instructor for a factory owner who offered evening classes for his employees. Legally, reading, writing and arithmetic were taught. Illegally, classes with a revolutionary influence were taught for those students who might be ready for them. Krupskaya and other instructors were relieved of duty when nearly 30,000 factory workers in the area went on strike for better wages.[25] Even after the revolution her emphasis was on "the problems of youth organization and education."[26] In order to become educated, they needed better access to books and materials.[27]

Pre-revolutionary Russian libraries had a tendency to exclude particular members. Some were exclusively for higher classes and some were only for employees of a particular company's "Trade Unions". In addition they also had narrow, orthodox literature. It was hard to find any books with new ideas, which is exactly why the underground libraries began. Another problem was the low level of literacy of the masses. Vyborg Library, designed by Alvar Aalto was renamed the Nadezhda Krupskaya Municipal Library after the Soviet annexation of Vyborg.

The revolution did not cause an overnight improvement in the libraries. In fact, for a while there were even more problems. The Trade Unions still refused to allow general public use, funds for purchasing books and materials were in short supply and books that were already a part of the libraries were falling apart. In addition there was a low interest in the library career field due to low income and the libraries were sorely in need of re-organization.

Krupskaya directed a census of the libraries in order to address these issues.[28] She encouraged libraries to collaborate and to open their doors to the general public. She encouraged librarians to use common speech when speaking with patrons. Knowing the workers needs was encouraged; what kind of books should be stocked, the subjects readers were interested in, and organizing the material in a fashion to better serve the readers. Committees were held to improve card catalogs.

Krupskaya stated at a library conference: "We have a laughable number of libraries, and their book stocks are even more inadequate. Their quality is terrible, the majority of the population does not know how to use them and does not even know what a library is."[29]

She also sought better professional schools for librarians. Formal training was scarce in pre-revolutionary Russia for librarians and it only truly began in the 20th century. Krupskaya, therefore, advocated the creation of library "seminaries" where practicing librarians would instruct aspiring librarians in the skills of their profession, similar to those in the West. The pedagogical characteristics were however those of the Soviet revolutionary period. Librarians were trained to determine what materials were suitable to patrons and whether or not they had the ability to appreciate what the resource had to offer.[30]

Krupskaya also desired that librarians possess greater verbal and writing skills so that they could more clearly explain why certain reading materials were better than others to their patrons. She believed that explaining resource choices to patrons was a courtesy and an opportunity for more education in socialist political values, not something that was required of the librarian. They were to become facilitators of the revolution and, later, those who helped preserve the values of the resulting socialist state.[30]

Krupskaya was a committed Marxist for whom each element of public education was a step toward improving the life of her people, granting all individuals access to the tools of education and libraries, needed to forge a more fulfilling life. The fulfillment was education and the tools were education and library systems.[31]

Legacy

- Following her death in 1939, a Leningrad chocolate factory was renamed in her honour. Krupskaya chocolate's chocolate bar product was named Krupskaya and retains that name today.[32]

- The asteroid 2071 Nadezhda discovered in 1971 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova was named in her honour.[33]

- Film director Mark Donskoy made a biographical film Nadezhda of her in 1974.

- In the 1974 BBC production Fall of Eagles, Krupskaya was portrayed by Lynn Farleigh.

- In 1974, Jane Barnes Casey wrote a fictional memoir of her life I, Krupskaya: My Life with Lenin (Houghton Mifflin Company; ISBN 0-395-18501-7).

- UNESCO named a prize in her honour, the UNESCO Nadezhda K. Krupskaya literacy prize.[34]

- In 1997, Nadezhda Krupskaya was portrayed by Estonian actress Helene Vannari in the Hardi Volmer directed Estonian historic comedy All My Lenins.

Gallery

Krupskaya (right) in 1936

Krupskaya (right) in 1936 Krupskaya (middle) in the 1930s

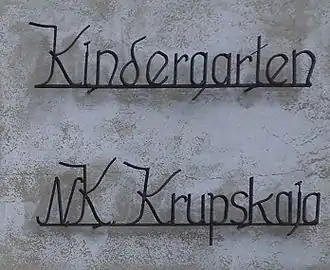

Krupskaya (middle) in the 1930s Board at a kindergarten in former East German part of Berlin-Spandau, Germany

Board at a kindergarten in former East German part of Berlin-Spandau, Germany

Footnotes

- Scientific transliteration: Nadežda Konstantinovna Krupskaja.

- McNeal, 13.

- Marcia Nell Boroughs Scott, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya: A flower in the dark. [Dissertation] The University of Texas at Arlington, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. 1383491.

- McNeal, 5–9.

- McNeal, 11–12.

- C. Bobrovskaija, Lenin and Krupskaja (New York City: Workers Library Publishers, Inc., 1940), 4.

- McNeal, 19.

- McNeal, 17–19.

- Mihail S. Skalkin, and Georgij S. Tsov’janov, “Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya," Prospects, Paris, Vol. 24, Issue 1 (1 January 1994): 49.

- "Tolstoy, Leo", in Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- McNeal, 23.

- Matietta Shaginyan, "Memories of Nadezhda Krupskaya", Soviet Literature, Moscow, Vol. 0, Issue 3 (1 January 1989): 156.

- "Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Barbara Evans Clements, Bolshevik Women, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Marcia Nell Boroughs Scott, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya: A flower in the dark. [Dissertation]. The University of Texas at Arlington, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1996. 1383491.

- Krupskaya. Reminiscences of Lenin. Moscow: Foreign Language Publishing House. 1959. p. 30

- H. Rappaport, Conspirator (London: Hutchinson, 2009), 200.

- Trotsky, Leon (1930). ""My Life", Chapter XII: The Party Congress and the Split". Marxists.org. Pathfinder Press. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- Nadezhda K. Krupskaya. The Lessons of October Source: The Errors of Trotskyism, Communist Party of Great Britain, May 1925.

- Leon Sedov. Red Book (Chap. 11) Source: Red Book, October 1936.

- Preface to the pamphlet "The New Law on Mother and Child", 1936.

- N. K. Krupskaya's. Reminiscences of Lenin, Foreign Language Publishing House, 1959.

- Toxic Politics: The Secret History of the Kremlin's Poison Laboratory―from the Special Cabinet to the Death of Litvinenko by Arkadi Vaksberg and Paul McGregor, ABC-Clio, ISBN 031338746X, pages 75-81

- Yuri Felshtinsky and Vladimir Pribylovsky, The Corporation. Russia and the KGB in the Age of President Putin, Encounter Books, ISBN 1-59403-246-7, February 25, 2009, page 445.

- Raymond, 53–55.

- McNeal, 173.

- Raymond, 171.

- N. K. Krupskaya, Part two : Krupskaia on libraries, ed Sylva Simsova (Hamden : Archon Books, 1968) 45–51.

- Raymond, 161.

- Richardson, John (2000). "The Origin of Soviet Education for Librarianship: The Role of Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869–1939), Lyubov' Borisovna Khavkina-Hamburger (1871–1949) and Genrietta K. Abele-Derman (1882–1954)" (PDF). Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. 41 (Spring 2000): 106–128 (115–117). doi:10.2307/40324059. ISSN 0748-5786.

- Raymond, 172.

- Crace, John (27 January 2010). "The Soviet chocolate named after Lenin's widow". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 168. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- Winners of the Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Priza and the Nadezhda K. Krupskaya Prize, UNESCO

Works

- Memories of Lenin. New York: International Publishers, 1930. —Reissued as Reminiscences of Lenin.

- On Education: Selected Articles and Speeches. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1957.

Further reading

- Clements, Barbara Evans, Bolshevik Women, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- McDermid, Jane and Anya Hilyar, "In Lenin's Shadow: Nadezhda Krupskaya and the Bolshevik Revolution," in Ian D. Thatcher (ed.), Reinterpreting Revolutionary Russia. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006; pp. 148–165.

- McNeal, Robert H., Bride of the Revolution: Krupskaya and Lenin. London: Gollancz, 1973.

- Raymond, Boris The Contribution of N. K. Krupskaia to the Development of Soviet Russian Librarianship: 1917–1939. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Chicago, 1978.

- Scott, Marcia Nell Boroughs, Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya: A Flower in the Dark. PhD dissertation. University of Texas at Arlington, 1996. Available from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1383491.

- Sebestyen, Victor, Lenin the Dictator: An Intimate Portrait. New York: Pantheon, 2017.

- Stites, Richard, The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860-1930. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nadezhda Krupskaya. |

- Nadezhda Krupskaya

- Krupskaya Internet Archive

- Obituary by Leon Trotsky

- Krupskaya on deathbed

- Newspaper clippings about Nadezhda Krupskaya in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW