Negative raising

In linguistics, negative raising is a phenomenon that concerns the raising of negation from the embedded or subordinate clause of certain predicates to the matrix or main clause.[1] The higher copy of the negation, in the matrix clause, is pronounced; but the semantic meaning is interpreted as though it were present in the embedded clause.[2]

Background

The NEG-element was first introduced by Edward Klima, but the term neg raising has been accredited to the early transformational analysis as an instance of movement.[3] Charles J. Fillmore was the first to propose a syntactic approach called neg transportation but is now known solely as negative raising. This syntactic approach was supported in the early beginnings by evidence provided by Robin Lakoff, who used, in part, strong/strict Polarity items as proof. Laurence R. Horn and Robin Lakoff have written on the theory of negative raising,[4][5] which is now considered to be the classical argumentation on this theory. Chris Collins and Paul Postal have also written in more recent times in defense of the classical argumentation to negative raising.[6][7] These early accounts attributed negative raising to be derived syntactically, as they thought that the NEG element was c-commanding onto two verbs. Not all agreed with the syntactic view of negative raising. To counter the syntactically derived theory of neg raising, Renate Bartsch and a number of others argued that a syntactic analysis was insufficient to explain all the components of the neg raising (NR) theory. Instead they developed a presuppositional, otherwise known as a semantically based account.[8]

English

In English, negative raising constructions utilize negation in the form of, "not," where it is then subject to clausal raising.[9]

In the phenomenon of negative raising, this negation cannot be raised freely with any given predicate.

Consider the following example proposed by Paul Crowley, in which the verb "say" attempts to display negative raising:[10]

- Mary didn’t say it would snow

- Mary said it would not snow.

As seen in this example, "say" is not a predicate that can be used for Neg-Raising, as the raising of the negation to the matrix clause creates the reading "Mary didn’t say it would snow," which holds a different meaning than "Mary said it would not snow," where the negation resides in the embedded clause.[11]

To account for this fact, Laurence Horn has identified 5 distinct classes to account for the general predicates involved negative raising, as seen below in English:[12]

| Class of Predicate | Examples |

|---|---|

| Opinion | think, believe, suppose, imagine, expect, reckon, feel |

| Perception | seem, appear, look like, sound like, feel like |

| Probability | be probable, be likely, figure to |

| Volition | want, intend, choose, plan |

| Judgement | be supposed to, ought, should, be desirable, advise, suggest |

Consider the Perception predicate, "look like," in which we can posit the following readings:

- “It looks like [it will not rain today]”

- “It does not look like [it will rain today]”

In this regard, “It does not look like [it will rain today]” is seen as a paraphrase of “It looks like [it will not rain today]." This is because even with the raising of the negation to the matrix clause, both sentences convey the same meaning, thus the matrix clause negation is to be interpreted as if it were within the embedded clause.[14]

Position and Scope of NEG

In English, syntactically we can have negative phrase structures with the NEG in the matrix clause - the semantic interpretation of these phrases can be ambiguous;[15]

- The negation could apply to the verb in the matrix clause

- The negation could apply to the verb in the embedded clause

Phrase structure with ambiguous and unambiguous NEG interpretation

| Phrase structure with NEG in Matrix clause | |

|---|---|

| Phrase | [DP I ] do not believe [TP we are having a review session] |

| Interpretation 1 | I don't believe that there's going to be a review session |

| Interpretation 2 | I believe that there is not going to be a review session |

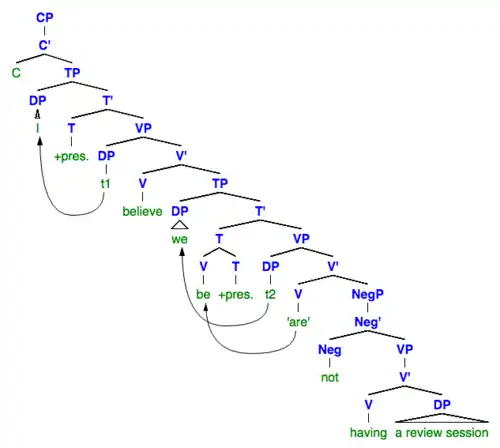

Syntax Tree 1

| Phrase structure with NEG in embedded clause | |

|---|---|

| Phrase | [DP I ] believe [TP we are not having a review session] |

| Interpretation | I believe that there is not going to be a review session |

Syntax Tree 2

The English language has a rich inventory of operators; these operators (in this case NEG specifically), differ from each other in terms of their scope orders with respect to other operators (in this case Verb). When we look at negative raising - we are thus looking at the operator NEG, and its scope over the Verbs in a phrase. Sentence with negative raising are thus ambiguous in terms of NEG -

- In one reading NEG has scope over the matrix verb (Tree 1)

- in the other reading NEG has scope over the clausal verb (Tree 2)

Phrase structure showing NEG Raising - from lower to upper position

.png.webp)

This tree illustrates how NEG can be raised from the embedded clause to the Matrix clause; thus it can be pronounced in the higher position while retaining its scope from the lower position.

Negative raising in other languages

Aside from English, negative raising has been an apparent phenomenon in a variety of languages:[16]

Modern Greek

negative raising works similar to English in Modern Greek but there appears to be clearer evidence of its existence in the language.[17]

This is evidenced in the usage of Negative Polarity Items and the usage of "αkόmα" (the time Adverb) in this language.

"αkόmα" (the time Adverb)

When the adverb αkόmα (translated as "yet" or"still" in English) is paired with a verb in the aorist, the negation "δεν" makes the clause grammatical (e.g δενaorist αkόmα) as it imperfectivises it. This clause cannot stand as an independent clause if the negation is not present, showing that the pair appear together in the same context (for it to be grammatical, another verb form would have to be used). However when the ungrammatical clause (e.g * aorist αkόmα) is embedded in a matrix clause, a negation appears before a "Neg-raiser" verb that is located in the higher clause - suggesting that the negation was moved from the embedded clause into the matrix clause.

Negative Polarity Items (NPI)

When an embedded clause (consisting an NPI) is embedded in a matrix clause (consisting a "Neg-raiser" verb), the negation could appear before or after the "Neg-raiser" verb. In both cases, the sentence would remain grammatical. However when a non "Neg-raiser" verb is used in the matrix clause, the negation is only allowed after the verb, before the embedded clause.

French

In French, evidence of negative raising can be demonstrated through the use of tag questions and corrective responses, where negation is primarily depicted by the negative construction, "ne...pas." ref>Prince, Ellen F. (1976). "The Syntax and Semantics of Neg-Raising, with Evidence from French". Language. 52 (2): 404–426. doi:10.2307/412568. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 412568.</ref>

Tag questions

When analyzing French tag questions, the tags 'oui' or 'non' are both seen with affirmative statements, while the tag 'non' is only selected by negative statements.

negative raising can be demonstrated through the observation that when the negation is in the embedded clause, it is able to take a tag. This can be seen through the use of the verb 'supposer,' to suppose, which coincides with Horn's proposed classes of negative-raising predicates:

| French + Tag | English Translation |

|---|---|

| i) Je suppose que Max est parti, oui / non? | I suppose Max has left, yes / no? |

| ii) Je ne suppose pas que Max soit parti, non? | I don't suppose Max has left, no? |

| iii) Je suppose que Max n'est pas parti, non? | I suppose Max hasn't left, no? |

Through this depiction, with both the matrix clause negation in ii) and embedded clause negation in iii) possessing the ability to take a tag, evidence is given that ii) surfaces via negative raising from the structures like iii). Thus, despite the movement of the negative "ne...pas" to the matrix clause, the meaning of ii) is seen as a paraphrase of iii).

Corrective responses

The use of corrective responses in French is similar to that of Tag Questions, with the exception that there are three attested answers to corrective responses: 'oui', 'si,' and 'non.' 'Oui' or 'non' are used to express affirmation, while negative questions are expressed by 'si' or 'non.'

As seen through the continued use of the verb 'supposer,' to suppose, negative raising can be demonstrated in the following examples:

| French | English Translation | Possible Responses in French |

|---|---|---|

| i) Je suppose que Jean vient de Djibouti | I suppose that Jean comes from Djibouti | Mais oui! / Mais non! |

| ii) Je suppose que Jean ne vient pas de Djibouti | I suppose that Jean does not come from Djibouti | Mais si! / Mais non! |

| iii) Je ne suppose pas que Jean vienne de Djibouti | I do not suppose that Jean comes from Djibouti | Mais si! / Mais non! |

In this data, it appears that the way in which the possible responses 'si'/'oui' are distributed relies upon the polarity of that to which it is a response. This statement further infers that negative raising is a process involved, given that ii) and iii) both permit the answer “Mais si!” or “Mais non!” despite the negation surfacing in separate clauses. This prompts evidence that they depict the same meaning despite the movement of the negation in the phrase, and thus, both structures originating their negation in the embedded clause.

Japanese

In Japanese, there are instances of neg-head raising.[18] This is evidenced, in part, through negative polarity items and the negative nai 'not'. It is suggested that one of the main differences between Japanese and English is that the extent of negative scope is based on whether there is or is not any neg-head raising to a higher position. In addition, neg-head raising has been to attributed to being responsible for clause-wide negative scope in Japanese.[19][20] This is different from English in that the negative scope in Japanese extends over the tense phrase (TP) because of neg-head raising.

Negative polarity item (NPIs)

In Japanese there are two types of NPIs: an argument modifier type and a floating modifier type. In Japanese, NPIs need to occur within the scope domain of the negator. What this means is that if the NPI were to occur in the matrix clause and the negator in the embedded clause, it would be considered to be ungrammatical, as it would not be within the scope domain of the negator. Another aspect which differentiates Japanese from English, in reference to Japanese NPIs, is that NPIs are considered to be legitimate regardless of whether they appear in the subject or the object position in simple verbal clauses.

Listed below are some example of Japanese NPIs.

| Japanese | English translation |

|---|---|

| dare-mo | anyone |

| amari | very |

| ken-sika | 'ken'-only |

Negative Nai 'Not'

Neg-head raising is also evidenced from the negative nai 'not'. The negative nai 'not' is neg-head raised, but it seems presently to only be raised when with a predicate with some verbal properties, as is shown by the NPI data. The evidence provided from the negative nai 'not' shows that the scope of nai moves from only being in the negative phrase (NegP) to extending over the tense phrase (TP). Additionally, when nai doesn't undergo neg-head raising, it results in subject-object/complement asymmetry.

Serbo-Croatian

In Serbo-Croation there is Obligatory NEG Raising in sentences which contain the ni-NPI accompanied by the NEG ne. This happens, as unlike English, SC does not have no-forms i.e Unary NEG structures, without a DP external NEG. Thus sentences in Serbo-Croation, lacking a clausally located NEG are ungrammatical. [21]

| Serbo-Croation | *Marija ce videti niko-ga |

|---|---|

| Gloss | Mary will see no-one-ACC |

Instead the raising process is employed;the underlying NEG ne originates in the lower embedded DP, and raises to the matrix, leaving behind a copy. Only the upper copy of the word is pronounced, so there is no possibility of an incorrect double negation analysis of the meaning. This can be seen as analogous to English sentences that contain a NEG internal to the DP combined with an NPI.

The structure of the sentence in these cases is as follows -

| Serbo-Croation | Mian NEG1, vidi [DP[D cNEG1 i] [NP šta]] |

|---|---|

| Gloss | Milan not see something |

References

- "NEG Raising", Classical NEG Raising, The MIT Press, 2014, doi:10.7551/mitpress/9704.003.0008, ISBN 978-0-262-32384-0

- Iatridou, Sabine; Sichel, Ivy (October 2011). "Negative DPs, A-Movement, and Scope Diminishment". Linguistic Inquiry. 42 (4): 595–629. doi:10.1162/ling_a_00062. hdl:1721.1/71143. ISSN 0024-3892.

- Lakoff, George (September 1970). "Global Rules". Language. 46 (3): 627–639. doi:10.2307/412310. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 412310.

- Seligson, Gerda; Lakoff, Robin T. (1969). "Abstract Syntax and Latin Complementation". The Classical World. 62 (9): 364. doi:10.2307/4346936. ISSN 0009-8418. JSTOR 4346936.

- Horn, Laurence R. (2001). A natural history of negation. CSLI. ISBN 1-57586-336-7. OCLC 47289406.

- Collins, Chris, 1963- (2014). Classical NEG raising : an essay on the syntax of negation. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02731-1. OCLC 890535311.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "NEG Raising", Classical NEG Raising, The MIT Press, 2014, doi:10.7551/mitpress/9704.003.0008, ISBN 978-0-262-32384-0

- Iatridou, Sabine; Sichel, Ivy (October 2011). "Negative DPs, A-Movement, and Scope Diminishment". Linguistic Inquiry. 42 (4): 595–629. doi:10.1162/ling_a_00062. hdl:1721.1/71143. ISSN 0024-3892.

- Jespersen, Otto (1917). Negation in English and other languages. Cornell University Library. København, A. F. Høst.

- Crowley, Paul (2019-03-01). "Neg-Raising and Neg movement". Natural Language Semantics. 27 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s11050-018-9148-0. ISSN 1572-865X.

- Crowley, Paul (2019-03-01). "Neg-Raising and Neg movement". Natural Language Semantics. 27 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s11050-018-9148-0. ISSN 1572-865X.

- Horn, Laurence R. (2001). A natural history of negation. Stanford, Calif.: CSLI. ISBN 1-57586-336-7. OCLC 47289406.

- Horn, Laurence R. (2001). A natural history of negation. Stanford, Calif.: CSLI. ISBN 1-57586-336-7. OCLC 47289406.

- Horn, Laurence R. (2001). A natural history of negation. Stanford, Calif.: CSLI. ISBN 1-57586-336-7. OCLC 47289406.

- Kroch, Anthony S (1974). The semantics of scope in English (Thesis). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept. of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics.

- Horn, Laurence R. (2001). A natural history of negation. Stanford, Calif.: CSLI. ISBN 1-57586-336-7. OCLC 47289406.

- Kakouriotis, A. (1987). "Negative Raising in Modern Greek". IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. 25 (1–4). doi:10.1515/iral.1987.25.1-4.303. ISSN 0019-042X.

- Kishimoto, Hideki (2017-02-03). "Negative polarity, A-movement, and clause architecture in Japanese" (PDF). Journal of East Asian Linguistics. 26 (2): 109–161. doi:10.1007/s10831-016-9153-6. ISSN 0925-8558.

- Kishimoto, Hideki (January 2007). "Negative scope and head raising in Japanese". Lingua. 117 (1): 247–288. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2006.01.003. ISSN 0024-3841.

- Kishimoto, Hideki (2008-11-03). "On Verb Raising". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195307344.013.0005.

- Collins, C., & Postal, P. M. (2017). "NEG raising and serbo-croatian NPIs". The Canadian Journal of Linguistics. 62 (3): 339–370. doi:10.1017/cnj.2017.2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)