Nizamuddin Markaz Mosque

Nizamuddin Markaz, also called Banglewali Masjid, is a mosque located in Nizamuddin West in South Delhi, India. It is the birthplace and the global headquarters of the Tablighi Jamaat network,[1][2] the missionary and reformist movement started by Muhammad Ilyas Kandhlawi in 1926.

| Nizamuddin Markaz Mosque | |

|---|---|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Masjid |

| Leadership | Muhammad Saad Kandhlawi |

| Location | |

| Location | Nizamuddin West |

| Country | India |

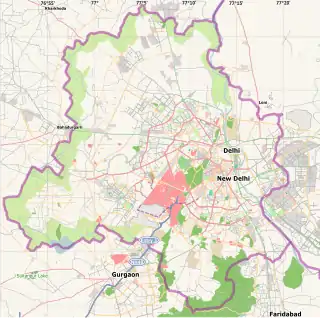

Shown within Delhi  Nizamuddin Markaz Mosque (India) | |

| Territory | Delhi |

| Geographic coordinates | 28.59157°N 77.24336°E |

| Architecture | |

| Completed | c. 1857 |

Since 2015, frictions developed within the group over the leadership of the organisation, and factions have developed. The mosque continues to serve as the headquarters of the Nizamuddin faction of Tablighi Jamaat.[3]

Building

The New York Times describes the Markaz as "a tall, white, modern building towering over the Nizamuddin West neighborhood".[2] It is said to be a centre of the neighbourhood's economy, with money changers, guesthouses, travel agencies and gift shops surrounding it and catering to the missionaries that visit the Markaz.[2]

The building is six stories high, and is capable of housing about 2,000 people. It is adjacent to the Hazrat Nizamuddin Police Station, with which it shares a wall. The famous Khawaja Nizamuddin Aulia shrine is close by.[4]

There is a Madrasa along with the Markaz Masjid named Kashiful Uloom.

Typical gatherings at the Markaz host 2,000–4,000 people. During the day, the large halls in the building are used for prayers and sermons. At night, they are used as sleeping quarters for 200–300 people on each floor.[5]

History

Early history

The Banglewali Masjid (Bungalow Mosque) was built in Nizamuddin by Mirza Ilahi Baksh, a relative of the last Mughal emperor, sometime after 1857. Mawlana Muhammad Ismail, the father of Muhammad Ilyas Kandhlawi, established a madrasa in its premises under the name Kashif al-Ulum. It is said that he used to go out and invite people to come to the mosque and, on one occasion, he happened to bring Meos from Mewat who were in Delhi as labourers. Noticing that they were not schooled in proper practice of prayer, he decided to teach it to them, which was the beginning of the madrasa.[6]

After the death of Mawlana Ismail and his elder son, Muammad Ilyas took up the task of teaching at the madrasa. He too was concerned with educating the Meos of Mewat.[7] Noticing that his own direct teaching would be indadequate to the task, in time, he evolved the practices of tabligh that form the foundation of Tablighi Jamaat.[8] This involved turning ordinary Muslims into preachers. Training them in the preaching work became the main activity of the madrasa, gradually turning the Banglewali Masjid into a markaz (centre or headquarters). Ilyas also set up an organisational network for his fledgling organisation bringing in men of influence to gather in the mosque. By the end of Ilyas's life, Tablighi Jamaat emerged as a national organisation with transnational potential.[9]

Transnational centre

Under Ilyas's son and successor, Muhammad Yusuf Kandhlawi (1917–1965), the Tablighi Jamaat expanded worldwide and became a transnational organisation.[10] The Nizamuddin Markaz became the world headquarters (Aalami Markaz). According to a commentator, it is "the heart circulating blood through the body" for the Tablighi Jamaat organisation.[11] It is the place where people are trained for missionary work, worldwide tours are organised and information to the entire worldwide network is distributed.[11]

After Yusuf's sudden death, the senior members chose Inamul Hasan Kandhlawi (1918–1995), a close relative of Ilyas, as the third amir.[12] However, some arugue that Hazrat Kandhlawi, Yusuf's brother, wielded more influence.[13] After the 30-year leadership of Inamul Hasan, during which the movement grew to its present size, an executive council (shura) was established to share the responsibilities of leadership.[12]

Recent developments

According to scholar Zacharias Pieri, the final decision-making responsibility fell on two men within the shura: Zubair ul-Hasan Kandhlawi and Muhammad Saad Kandhlawi.[14] After Zubair ul-Hasan's death in 2014, Mawlana Saad assumed the leadership of the council and the movement.[15] According to The Milli Gazette, the senior members of the Tablighi Jamaat from around the world met at the Pakistan regional markaz at Raiwind in 2015 and resolved that the organisation would be governed by a shura. Raiwind amir Muhammad Abdul Wahhab who was a member of the original shura backed this effort.[3][16] Mawlana Saad did not accept the recommendations of the meeting, causing a split in the organisation.[3]

The friction led to division of the Tablighi Jamaat leadership into two groups, the first being led by Muhammad Saad Kandhlawi at the Nizamuddin Markaz, while the other being led by Ebrahim Dewla, Ahmed Laat and others at Nerul Markaz in India.[17] The Raiwind Markaz in Pakistan is part of the latter group and has become the "de facto base" of the aalami shura group.[18][16]

COVID-19 pandemic

The mosque organised a large congregation in March 2020, from 13 to 15 March, participants got stuck in the Markaz Building due to the sudden and surprize announcement of nationwide lockdown in India by the government. Although prior information was furnished with the Nizamiddin Police station, and parellel functions were also held near the same dates (belonging to other religions), some right wing media outlets made a big propaganda of this event as reason for Corona spread in the state. https://scroll.in/latest/964211/covid-19-residents-of-nizamuddin-serve-legal-notice-to-delhi-authorities-for-targeting-muslims

See also

- Nerul Aalami Markaz, in Maharashtra

- Raiwind Markaz, in Pakistan

- Tongi Ijtema, in Bangladesh

References

- Uday Mahurkar, Tablighi Jamaat's defiance spreads concern, India Today, 1 April 2020.

- Jeffrey Gettleman, Kai Schultz, Suhasini Raj, In India, Coronavirus Fans Religious Hatred, The New York Times, 12 April 2020.

- M. Burhanuddin Qasmi (30 July 2016). "Tablighi Jamaat at the crossroads". The Milli Gazette.

- Nizamuddin Markaz: State-wise list of nearly 2,000 people who attended Tablighi Jamaat in March, India TV, 31 March 2020.

- Reuters, The Religious Retreat That Sparked India's Major Coronavirus Manhunt, The New York Times, 2 April 2020.

- Kuiper (2017), pp. 168–169.

- Kuiper (2017), p. 173.

- Kuiper (2017), pp. 179.

- Kuiper (2017), pp. 180–182.

- Pieri (2015), p. 60.

- Pieri (2015), p. 65.

- Pieri (2015), p. 61.

- Pieri (2015), p. 61: "Mayaram argues that the process of succession has not been fluid. Some in TJ allege that after Yusuf’s death, his brother, Hazrat Kandhalawi, started to “dominate the decision making structure at Nizamuddin,” with even the official amir having to consult him before decisions were made. It was from this split that the trend toward a dual hereditary leadership emerged."

- Pieri (2015), p. 61: "Since Izhar ul-Hasan’s death in 1996, the governing executive council was made up of Zubayr and Saad (Arshad 2007).[3] In the strictest sense, the final decision-making powers in the movement fell to these two men."

- Pieri (2015), p. 61: "In 2014, there was yet another change in TJ’s leadership with the passing away of Zubayr ul-Hasan. Zubayr was seen as the senior leader in the movement and teacher of the current leader Maulana Saad. ... Reetz commented that even before Maulana Zubayr’s death, Maulana Saad moved to the center of the movement and was seen as the “spiritual and symbolic head” attracting immense popularity on an international level."

- Ghazali, Abdus Satar (12 October 2018). "Global leadership split in Tablighi Jamaat echoes in San Francisco Bay Area". countercurrents.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Mohammed Wajihuddin (1 April 2020). "How Tablighi movement split into two groups two years ago". The Times of India.

- Timol, Riyaz (14 October 2019). "Structures of Organisation and Loci of Authority in a Glocal Islamic Movement: The Tablighi Jama'at in Britain". Religions. 10 (10). doi:10.3390/rel10100573. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

Bibliography

- Kuiper, Matthew J. (2017), Da'wa and Other Religions: Indian Muslims and the Modern Resurgence of Global Islamic Activism, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-351-68170-4

- Pieri, Zacharias P. (2015), Tablighi Jamaat and the Quest for the London Mega Mosque: Continuity and Change, Springer, ISBN 978-1-137-46439-2