Nonconformist (Protestantism)

In English church history, a Nonconformist was a Protestant who did not "conform" to the governance and usages of the established Church of England. Broad use of the term was precipitated after the Restoration of the British monarchy in 1660, when the Act of Uniformity 1662 re-established the opponents of reform within the Church of England. By the late 19th century the term specifically included the Reformed Christians (Presbyterians, Congregationalists and other Calvinist sects), plus the Baptists and Methodists. The English Dissenters such as the Puritans who violated the Act of Uniformity 1559—typically by practising radical, sometimes separatist, dissent—were retrospectively labelled as Nonconformists.

By law and social custom, Nonconformists were restricted from many spheres of public life—not least, from access to public office, civil service careers, or degrees at university—and were referred to as suffering from civil disabilities. In England and Wales in the late 19th century the new terms "free churchman" and "Free Church" started to replace "dissenter" or "Nonconformist".[1]

One influential Nonconformist minister was Matthew Henry, who beginning in 1710 published his multi-volume Commentary that is still used and available in the 21st century. Isaac Watts is an equally recognized Nonconformist minister whose hymns are still sung by Christians worldwide.

Origins

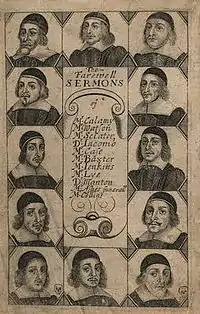

The Act of Uniformity of 1662 required churchmen to use all rites and ceremonies as prescribed in the Book of Common Prayer.[2] It also required episcopal ordination of all ministers of the Church of England—a pronouncement most odious to the Puritans, the faction of the church which had come to dominance during the English Civil War and the Interregnum. Consequently, nearly 2,000 clergymen were "ejected" from the established church for refusing to comply with the provisions of the act, an event referred to as the Great Ejection.[2] The Great Ejection created an abiding public consciousness of non-conformity.

Thereafter, a Nonconformist was any English subject belonging to a non-Anglican church or a non-Christian religion. More broadly, any person who advocated religious liberty was typically called out as Nonconformist.[3] The strict religious tests embodied in the laws of the Clarendon Code and other penal laws excluded a substantial section of English society from public affairs and benefits, including certification of university degrees, for well more than a century and a half. Culturally, in England and Wales, discrimination against Nonconformists endured even longer.

Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Calvinists, other "reformed" groups and less organized sects were identified as Nonconformists at the time of the 1662 Act of Uniformity. Following the act, other groups, including Methodists, Unitarians, Quakers, Plymouth Brethren, and the English Moravians were officially labelled as Nonconformists as they became organized.[4]

The term dissenter later came into particular use after the Act of Toleration (1689), which exempted those Nonconformists who had taken oaths of allegiance from being penalized for certain acts, such as for non-attendance to Church of England services.[5]

A census of religion in 1851 revealed Nonconformists made up about half the number of people who attended church services on Sundays. In the larger manufacturing areas, Nonconformists clearly outnumbered members of the Church of England.[6] In Wales in 1850, Nonconformist chapel attendance significantly outnumbered Anglican church attendance.[7] They were based in the fast-growing upwardly mobile urban middle class.[8]

Nonconformist conscience

Historians distinguish two categories of Dissenters, or Nonconformists, in addition to the evangelicals or "Low Church" element in the Church of England. "Old Dissenters", dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, included Baptists, Congregationalists, Quakers, Unitarians, and Presbyterians outside Scotland. "New Dissenters" emerged in the 18th century and were mainly Methodists. The "Nonconformist Conscience" was their moral sensibility which they tried to implement in British politics.[9] The "Nonconformist conscience" of the Old group emphasized religious freedom and equality, pursuit of justice, and opposition to discrimination, compulsion, and coercion. The New Dissenters (and also the Anglican evangelicals) stressed personal morality issues, including sexuality, temperance, family values, and Sabbath-keeping. Both factions were politically active, but until mid-19th century the Old group supported mostly Whigs and Liberals in politics, while the New—like most Anglicans—generally supported Conservatives. In the late 19th the New Dissenters mostly switched to the Liberal Party. The result was a merging of the two groups, strengthening their great weight as a political pressure group. They joined together on new issues especially regarding schools and temperance.[10][11] By 1914 the linkage was weakening and by the 1920s it was virtually dead.[12]

Nonconformists in the 18th and 19th century claimed a devotion to hard work, temperance, frugality, and upward mobility, with which historians today largely agree. A major Unitarian magazine, the Christian Monthly Repository asserted in 1827:

Throughout England a great part of the more active members of society, who have the most intercourse with the people have the most influence over them, are Protestant Dissenters. These are manufacturers, merchants and substantial tradesman, or persons who are in the enjoyment of a competency realized by trade, commerce and manufacturers, gentlemen of the professions of law and physic, and agriculturalists, of that class particularly who live upon their own freehold. The virtues of temperance, frugality, prudence and integrity promoted by religious Nonconformity...assist the temporal prosperity of these descriptions of persons, as they tend also to lift others to the same rank in society.[13]

Women

The emerging middle-class norm for women was separate spheres, whereby women avoid the public sphere—the domain of politics, paid work, commerce and public speaking. Instead they should dominate in the realm of domestic life, focused on care of the family, the husband, the children, the household, religion, and moral behaviour.[14] Religiosity was in the female sphere, and the Nonconformist churches offered new roles that women eagerly entered. They taught Sunday school, visited the poor and sick, distributed tracts, engaged in fundraising, supported missionaries, led Methodist class meetings, prayed with other women, and a few were allowed to preach to mixed audiences.[15]

Politics

Disabilities removed

Parliament had imposed a series of disabilities on Nonconformists that prevented them from holding most public offices, that required them to pay local taxes to the Anglican church, be married by Anglican ministers, and be denied attendance at Oxford or degrees at Cambridge.[16] Dissenters demanded removal of political and civil disabilities that applied to them (especially those in the Test and Corporation Acts). The Anglican establishment strongly resisted until 1828.[17] The Test Act of 1673 made it illegal for anyone not receiving communion in the Church of England to hold office under the crown. The Corporation Act of 1661 did likewise for offices in municipal government. In 1732, Nonconformists in the City of London created an association, the Dissenting Deputies to secure repeal of the Test and Corporation acts. The Deputies became a sophisticated pressure group, and worked with liberal Whigs to achieve repeal in 1828. It was a major achievement for an outside group, but the Dissenters were not finished.[18]

Next on the agenda was the matter of church rates, which were local taxes at the parish level for the support of the parish church building in England and Wales. Only buildings of the established church received the tax money. Civil disobedience was attempted, but was met with seizure of personal property and even imprisonment. The compulsory factor was finally abolished in 1868 by William Ewart Gladstone, and payment was made voluntary.[19] While Gladstone was a moralistic evangelical inside the Church of England, he had strong support in the Nonconformist community.[20][21] The marriage question was settled by Marriage Act 1836 which allowed local government registrars to handle marriages. Nonconformist ministers in their own chapels were allowed to marry couples if a registrar was present. Also in 1836, civil registration of births, deaths and marriages was taken from the hands of local parish officials and given to local government registrars. Burial of the dead was a more troubling problem, for urban chapels rarely had graveyards, and sought to use the traditional graveyards controlled by the established church. The Burials Act of 1880 finally allowed that.[22]

Oxford University required students seeking admission to submit to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. Cambridge University required that for a diploma. The two ancient universities opposed giving a charter to the new London University in the 1830s, because it had no such restriction. London University, nevertheless, was established in 1836, and by the 1850s Oxford dropped its restrictions. In 1871 Gladstone sponsored legislation that provided full access to degrees and fellowships. The Scottish universities never had restrictions.[23]

Impact on politics

Since 1660, nonconformist Protestants have played a major role in English politics.

The Nonconformist cause was linked closely to the Whigs, who advocated civil and religious liberty. After the Test and Corporation Acts were repealed in 1828, all the Nonconformists elected to Parliament were Liberals.[6]

Relatively few MPs were Dissenters. However the Dissenters were major voting bloc in many areas, such as East Midlands.[24] They were very well organized and highly motivated and largely won over the Whigs and Liberals to their cause. Gladstone brought the majority of dissenters around to support for Home Rule for Ireland, putting the dissenting Protestants in league with the Irish Roman Catholics in an otherwise unlikely alliance. The dissenters gave significant support to moralistic issues, such as temperance and sabbath enforcement. The nonconformist conscience, as it was called, was repeatedly called upon by Gladstone for support for his moralistic foreign policy.[9] In election after election, Protestant ministers rallied their congregations to the Liberal ticket. In Scotland, the Presbyterians played a similar role to the Nonconformist Methodists, Baptists and other groups in England and Wales[25] The political strength of Dissent faded sharply after 1920 with the secularization of British society in the 20th century. The rise of the Labour Party reduced the Liberal Party strongholds into the nonconformist and remote "Celtic Fringe", where it survived by an emphasis on localism and historic religious identity, thereby neutralizing much of the class pressure on behalf of the Labour movement.[26] Meanwhile, the Anglican church was a bastion of strength for the Conservative Party. On the Irish issue, the Anglicans strongly supported unionism. Increasingly after 1850, the Roman Catholic element in England and Scotland consisted of recent immigrants from Ireland. They voted largely for the Irish Parliamentary Party, until its collapse in 1918.[26]

Nonconformists were angered by the Education Act 1902, which provided for the support of denominational schools from taxes. The elected local school boards that they largely controlled were abolished and replaced by county-level local education authorities (LEAs) that were usually controlled by Anglicans. Worst of all the hated Anglican schools would now receive funding from local taxes that everyone had to pay. One tactic was to refuse to pay local taxes. John Clifford formed the National Passive Resistance Committee. By 1904 over 37,000 summonses for unpaid school taxes were issued, with thousands having their property seized and 80 protesters going to prison. It operated for another decade but had no impact on the school system.[27][28][29] The education issue played a major role in the Liberal victory in the 1906 general election, as Dissenter Conservatives punished their old party and voted Liberal. After 1906, a Liberal attempt to modify the law was blocked by the Conservative-dominated House of Lords; after 1911 when the Lords had been stripped of its veto over legislation, the issue was no longer of high enough priority to produce Liberal action.[30]

Today

Today, Protestant churches independent of the Anglican Church of England or the Presbyterian Church of Scotland are often called "free churches", meaning they are free from state control. This term is used interchangeably with "Nonconformist". In Scotland, the Anglican Scottish Episcopal Church is considered Nonconformist (despite its English counterpart's status) and in England, the United Reformed Church, principally a union of Presbyterians and Congregationalists, is in a similar position.

In Wales, the strong traditions of Nonconformism can be traced to the Welsh Methodist revival; Wales effectively had become a Nonconformist country by the mid-19th century. The influence of Nonconformism in the early part of the 20th century, boosted by the 1904–1905 Welsh Revival, led to the disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Wales in 1920 and the formation of the Church in Wales.

The steady pace of secularization picked up faster and faster during the 20th century, until only pockets of nonconformist religiosity remained in Britain.[31][32][33]

See also

References

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966) p 370

- Choudhury 2005, p. 173

- Reynolds 2003, p. 267

- "Nonconformist (Protestant)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Cross 1997, p. 490

- Mitchell 2011, p. 547

- "Religion in 19th and 20th century Wales". BBC History. BBC. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Michael R. Watts (2015). The Dissenters: The crisis and conscience of nonconformity. Clarendon Press. p. 105.

- D. W. Bebbington, The Nonconformist Conscience: Chapel and Politics, 1870–1914 (George Allen & Unwin, 1982).

- Timothy Larsen, "A Nonconformist Conscience? Free Churchmen in Parliament in Nineteenth-Century England". Parliamentary History 24#1 (2005): 107–119. doi:10.1111/j.1750-0206.2005.tb00405.x.

- Richard Helmstadter, "The Nonconformist Conscience" in Peter Marsh, ed., The Conscience of the Victorian State (1979) pp. 135–72.

- John F. Glaser, "English Nonconformity and the Decline of Liberalism". American Historical Review 63.2 (1958): 352–363. doi:10.1086/ahr/63.2.352. JSTOR 1849549.

- Richard W. Davis, "The Politics of the Confessional State, 1760–1832." Parliamentary History 9.1 (1990): 38–49, doi:10.1111/j.1750-0206.1990.tb00552.x, quote p. 41

- Robyn Ryle (2012). Questioning gender: a sociological exploration. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE/Pine Forge Press. pp. 342–43. ISBN 978-1-4129-6594-1.

- Linda Wilson, "'Constrained by Zeal': Women in Mid‐Nineteenth Century Nonconformist Churches." Journal of Religious History 23.2 (1999): 185–202. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.00081.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966) pp. 60–95, 142–58

- G. I. T. Machin, "Resistance to Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1828". Historical Journal 22#1 (1979): 115–139. JSTOR 2639014. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00016708.

- Richard W. Davis, "The Strategy of 'Dissent' in the Repeal Campaign, 1820–1828". Journal of Modern History 38.4 (1966): 374–393. JSTOR 1876681.

- Olive Anderson, "Gladstone's Abolition of Compulsory Church Rates: a Minor Political Myth and its Historiographical Career". Journal of Ecclesiastical History 25#2 (1974): 185–198. doi:10.1017/S0022046900045735.

- G. I. T. Machin, "Gladstone and Nonconformity in the 1860s: The Formation of an Alliance". Historical Journal 17 (1974): 347–364. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00007780. JSTOR 2638302.

- Jacob P. Ellens, Religious Routes to Gladstonian Liberalism: The Church Rate Conflict in England and Wales 1852–1868 (2010).

- Richard Helmstadter, "The Nonconformist Conscience" in Peter Marsh, ed., The Conscience of the Victorian State (1979) pp. 144–147.

- Helmstadter, "The Nonconformist Conscience" p. 147.

- Henry Pelling, Social Geography of British Elections, 1885–1910 (1967) 89–90, 206,

- David L. Wykes, "Introduction: Parliament and Dissent from the Restoration to the Twentieth Century", Parliamentary History (2005) 24#1 pp. 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1750-0206.2005.tb00399.x.

- Iain MacAllister et al., "Yellow fever? The political geography of Liberal voting in Great Britain", Political Geography (2002) 21#4 pp. 421–447. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00077-4.

- Donald Read (1994). The age of urban democracy, England, 1868–1914. Longman. p. 428.

- D. R. Pugh, "English Nonconformity, education and passive resistance 1903–6". History of Education 19#4 (1990): 355–373. doi:10.1080/0046760900190405.

- N. R. Gullifer, "Opposition to the 1902 Education Act", Oxford Review of Education (1982) 8#1 pp. 83–98. doi:10.1080/0305498820080106. JSTOR 1050168.

- Élie Halévy, The Rule of Democracy (1905–1914) (1956). pp 64–90.

- Steve Bruce, and Tony Glendinning, "When was secularization? Dating the decline of the British churches and locating its cause". British Journal of Sociology 61#1 (2010): 107–126. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01304.x.

- Callum G. Brown, The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation, 1800–2000 (2009)

- Alan D. Gilbert, The making of post-Christian Britain: a history of the secularization of modern society (Longman, 1980).

Further reading

- Bebbington, David W. Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s (Routledge, 2003)

- Bebbington, David W. "Nonconformity and electoral sociology, 1867–1918." Historical Journal 27#3 (1984): 633–656. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00018008.

- Binfield, Clyde. So down to prayers: studies in English nonconformity, 1780–1920 (JM Dent & Sons, 1977).

- Bradley, Ian C. The Call to Seriousness: The Evangelical Impact on the Victorians (1976), Covers the Evangelical wing of the established Church of England

- Brown, Callum G. The death of Christian Britain: understanding secularisation, 1800–2000 (Routledge, 2009).

- Choudhury, Bibhash (2005), English Social and Cultural History: An Introductory Guide and Glossary (2 ed.), PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd, ISBN 8120328493

- Cowherd, Raymond G. The Politics of English Dissent: The Religious Aspects of Liberal and Humanitarian Reform Movements from 1815 to 1848 (1956).

- Cross, F.L. (1997), E.A. Livingstone (ed.), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Davies, Gwyn (2002), A light in the land: Christianity in Wales, 200–2000, Bridgend: Bryntirion Press, ISBN 1-85049-181-X

- Ellens, Jacob. Religious Routes to Gladstonian Liberalism: The Church Rate Conflict in England and Wales 1852–1868 (Penn State Press, 1994).

- Hempton, David. Methodism and Politics in British Society 1750–1850 (1984)

- Koss, Stephen. Nonconformity in Modem British Politics (1975)

- Mitchell, Sally (2011), Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia, London: Taylor & Francis Ltd, ISBN 0415668514

- Machin, G. I. T. "Gladstone and Nonconformity in the 1860s: The Formation of an Alliance." Historical Journal 17, no. 2 (1974): 347-64. online.

- Mullett, Charles F. "The Legal Position of English Protestant Dissenters, 1689–1767." Virginia Law Review (1937): 389–418. JSTOR 1067999. doi:10.2307/1067999.

- Payne, Ernest A. The Free Church Tradition in the Life of England (1944), well-documented brief survey.

- Riglin, Keith and Julian Templeton, eds. Reforming Worship: English Reformed Principles and Practice. (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2012).

- Wellings, Martin, ed. Protestant Nonconformity and Christian Missions (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2014).

- Wilson, Linda. "'Constrained by Zeal': Women in Mid‐NineteenthCentury Nonconformist Churches." Journal of Religious History 23.2 (1999): 185–202. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.00081.</ref>

- Wilson, Linda. Constrained by Zeal: Female Spirituality Amongst Nonconformists, 1825–75 (Paternoster, 2000).