Oman

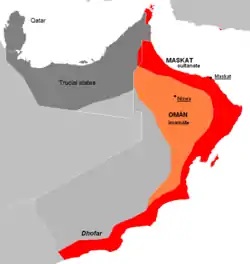

Oman (/oʊˈmɑːn/ (![]() listen) oh-MAHN; Arabic: عُمَان ʿUmān [ʕʊˈmaːn]), officially the Sultanate of Oman (Arabic: سلْطنةُ عُمان Salṭanat(u) ʻUmān), is a country on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia and the oldest independent state in the Arab world.[8][9] Located in a strategically important position at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, the country shares land borders with the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west, and Yemen to the southwest, and shares marine borders with Iran and Pakistan. The coast is formed by the Arabian Sea on the southeast and the Gulf of Oman on the northeast. The Madha and Musandam exclaves are surrounded by the UAE on their land borders, with the Strait of Hormuz (which it shares with Iran) and the Gulf of Oman forming Musandam's coastal boundaries.

listen) oh-MAHN; Arabic: عُمَان ʿUmān [ʕʊˈmaːn]), officially the Sultanate of Oman (Arabic: سلْطنةُ عُمان Salṭanat(u) ʻUmān), is a country on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in Western Asia and the oldest independent state in the Arab world.[8][9] Located in a strategically important position at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, the country shares land borders with the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west, and Yemen to the southwest, and shares marine borders with Iran and Pakistan. The coast is formed by the Arabian Sea on the southeast and the Gulf of Oman on the northeast. The Madha and Musandam exclaves are surrounded by the UAE on their land borders, with the Strait of Hormuz (which it shares with Iran) and the Gulf of Oman forming Musandam's coastal boundaries.

Sultanate of Oman سلطنة عُمان (Arabic) Salṭanat ʻUmān | |

|---|---|

_(orthographic_projection).svg.png.webp) Location of Oman in the Arabian Peninsula (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Muscat 23°35′20″N 58°24′30″E |

| Official languages | Arabic[1] |

| Religion | Islam (official) |

| Demonym(s) | Omani |

| Government | Unitary absolute monarchy |

• Sultan | Haitham bin Tariq Al Said |

| Legislature | Council of Oman |

| Council of State (Majlis al-Dawla) | |

| Consultative Assembly (Majlis al-Shura) | |

| Establishment | |

• The Azd tribe migration | 130 |

• Al-Julanda | 629 |

| 751 | |

| 1154 | |

| 1624 | |

• Al Said dynasty | 1744 |

| 8 January 1820 | |

| 1954–1959 | |

| 9 June 1965 – 11 December 1975 | |

• Sultanate of Oman | 9 August 1970 |

• Admitted to the United Nations | 7 October 1971 |

| 6 November 1996 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 309,500 km2 (119,500 sq mi) (70th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 4,829,473[3][4] (125th) |

• 2010 census | 2,773,479[5] |

• Density | 15/km2 (38.8/sq mi) (177th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $203.959 billion[6] (67th) |

• Per capita | $47,366[6] (23rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $62.305 billion[6] (75th) |

• Per capita | $14,423[6] (49th) |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 60th |

| Currency | Omani rial (OMR) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (GST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +968 |

| ISO 3166 code | OM |

| Internet TLD | .om, عمان. |

Website www.oman.om | |

From the late 17th century, the Omani Sultanate was a powerful empire, vying with the Portuguese Empire and the British Empire for influence in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. At its peak in the 19th century, Omani influence or control extended across the Strait of Hormuz to modern-day Iran and Pakistan, and as far south as Zanzibar.[10] When its power declined in the 20th century, the sultanate came under the influence of the United Kingdom. For over 300 years, the relations built between the two empires were based on mutual benefits. The UK recognized Oman's geographical importance as a trading hub that secured their trading lanes in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean and protected their empire in the Indian sub-continent. Historically, Muscat was the principal trading port of the Persian Gulf region. Muscat was also among the most important trading ports of the Indian Ocean.

Sultan Qaboos bin Said al Said was the hereditary leader of the country, which is an absolute monarchy, from 1970 until his death on 10 January 2020.[11] His cousin, Haitham bin Tariq, was named as the country's new ruler following his death.[12]

Oman is a member of the United Nations, the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. It has sizeable oil reserves, ranking 25th globally.[8][13] In 2010, the United Nations Development Programme ranked Oman as the most improved nation in the world in terms of development during the preceding 40 years.[14] A significant portion of its economy involves tourism and trading fish, dates and other agricultural produce. Oman is categorized as a high-income economy and ranks as the 69th most peaceful country in the world according to the Global Peace Index.[15]

Etymology

The origin of Oman's name is uncertain. It seems to be related to Pliny the Elder's Omana[16] and Ptolemy's Omanon (Ὄμανον ἐμπόριον in Greek),[17] both probably the ancient Sohar.[18] The city or region is typically etymologized in Arabic from aamen or amoun ("settled" people, as opposed to the Bedouin),[18] although a number of eponymous founders have been proposed (Oman bin Ibrahim al-Khalil, Oman bin Siba' bin Yaghthan bin Ibrahim, Oman bin Qahtan and the Biblical Lot) and others derive it from the name of a valley in Yemen at Ma'rib presumed to have been the origin of the city's founders, the Azd, a tribe migrating from Yemen.[19]

History

Prehistory and ancient history

At Aybut Al Auwal, in the Dhofar Governorate of Oman, a site was discovered in 2011 containing more than 100 surface scatters of stone tools, belonging to a regionally specific African lithic industry—the late Nubian Complex—known previously only from the northeast and Horn of Africa. Two optically stimulated luminescence age estimates place the Arabian Nubian Complex at 106,000 years old. This supports the proposition that early human populations moved from Africa into Arabia during the Late Pleistocene.[20]

In recent years surveys have uncovered Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites on the eastern coast. Main Palaeolithic sites include Saiwan-Ghunaim in the Barr al-Hikman.[21] Archaeological remains are particularly numerous for the Bronze Age Umm an-Nar and Wadi Suq periods. Sites such as Bat show professional wheel-turned pottery, excellent hand-made stone vessels, a metals industry and monumental architecture .[22] The Early (1300‒300 BC) and Late Iron Ages (100 BC‒300 AD) show more differences than similarities to each other. Thereafter, until the coming of Ibadi Islam, little or nothing is known.

During the 8th century BC, it is believed that the Yaarub, the descendant of Kahtan, ruled the entire region of Yemen, including Oman. Wathil bin Himyar bin Abd-Shams-Saba bin Jashjub bin Yaarub later ruled Oman.[23] It is thus believed that the Yaarubah were the first settlers in Oman from Yemen.[24]

In the 1970s and 1980s scholars like John C. Wilkinson[25] believed by virtue of oral history that in the 6th century BC, the Achaemenids exerted control over the Omani peninsula, most likely ruling from a coastal centre such as Suhar.[26] Central Oman has its own indigenous Samad Late Iron Age cultural assemblage named eponymously from Samad al-Shan. In the northern part of the Oman Peninsula the Recent Pre-Islamic Period begins in the 3rd century BC and extends into the 3rd A.D. century. Whether or not Persians brought south-eastern Arabian under their control is a moot point, since the lack of Persian finds speak against this belief. M. Caussin de Percevel suggests that Shammir bin Wathil bin Himyar recognized the authority of Cyrus the Great over Oman in 536 B.C.[23]

Sumerian tablets referred to Oman as "Magan"[27][28] and in the Akkadian language "Makan",[29][30] a name which links Oman's ancient copper resources.[31] Mazoon, a Persian name used to refer to Oman's region, which was part of the Sasanian Empire.

Arab settlement

Over centuries tribes from western Arabia settled in Oman, making a living by fishing, farming, herding or stock breeding, and many present day Omani families trace their ancestral roots to other parts of Arabia. Arab migration to Oman started from northern-western and south-western Arabia and those who chose to settle had to compete with the indigenous population for the best arable land. When Arab tribes started to migrate to Oman, there were two distinct groups. One group, a segment of the Azd tribe migrated from the southwest of Arabia in A.D. 120[32]/200 following the collapse of Marib Dam, while the other group migrated a few centuries before the birth of Islam from central and northern Arabia, named Nizari (Nejdi). Other historians believe that the Yaarubah, like the Azd, from Qahtan but belong to an older branch, were the first settlers of Oman from Yemen, and then came the Azd.[24]

The Azd settlers in Oman are descendants of Nasr bin Azd, a branch of Yaarub bin Qahtan, and were later known as "the Al-Azd of Oman".[32] Seventy years after the first Azd migration, another branch of Alazdi under Malik bin Fahm, the founder of Kingdom of Tanukhites on the west of Euphrates, is believed to have settled in Oman.[32] According to Al-Kalbi, Malik bin Fahm was the first settler of Alazd.[33] He is said to have first settled in Qalhat. By this account, Malik, with an armed force of more than 6000 men and horses, fought against the Marzban, who served an ambiguously named Persian king in the battle of Salut in Oman and eventually defeated the Persian forces.[24][34][35][36][37] This account is, however, semi-legendary and seems to condense multiple centuries of migration and conflict into a story of two campaigns that exaggerate the success of the Arabs. The account may also represent an amalgamation of various traditions from not only the Arab tribes but also the region's original inhabitants. Furthermore, no date can be determined for the events of this story.[35][38][39]

In the 7th century AD, Omanis came in contact with and accepted Islam.[40][41] The conversion of Omanis to Islam is ascribed to Amr ibn al-As, who was sent by the prophet Muhammad during the Expedition of Zaid ibn Haritha (Hisma). Amer was dispatched to meet with Jaifer and Abd, the sons of Julanda who ruled Oman. They appear to have readily embraced Islam.[42]

Imamate of Oman

Omani Azd used to travel to Basra for trade, which was a centre of Islam during the Umayyad empire. Omani Azd were granted a section of Basra, where they could settle and attend their needs. Many of the Omani Azd who settled in Basra became wealthy merchants and under their leader Muhallab bin Abi Sufrah started to expand their influence of power eastwards towards Khorasan. Ibadhi Islam originated in Basra by its founder Abdullah ibn Ibada around the year 650 CE, which the Omani Azd in Iraq followed. Later, Alhajjaj, the governor of Iraq, came into conflict with the Ibadhis, which forced them out to Oman. Among those who returned to Oman was the scholar Jaber bin Zaid. His return and the return of many other scholars greatly enhanced the Ibadhi movement in Oman.[43] Alhajjaj, also made an attempt to subjugate Oman, which was ruled by Suleiman and Said, the sons of Abbad bin Julanda. Alhajjaj dispatched Mujjaah bin Shiwah who was confronted by Said bin Abbad. The confrontation devastated Said's army. Thus, Said and his forces resorted to the Jebel Akhdar. Mujjaah and his forces went after Said and his forces and succeeded in besieging them from a position in "Wade Mastall". Mujjaah later moved towards the coast where he confronted Suleiman bin Abbad. The battle was won by Suleiman's forces. Alhajjaj, however, sent another force under Abdulrahman bin Suleiman and eventually won the war and took over the governance of Oman.[44][45][46]

The first elective Imamate of Oman is believed to have been established shortly after the fall of the Umayyad Dynasty in 750/755 AD when Janah bin Abbada Alhinawi was elected.[43][47] Other scholars claim that Janah bin Abbada served as a Wali (governor) under Umayyad dynasty and later ratified the Imamate, while Julanda bin Masud was the first elected Imam of Oman in A.D. 751.[48][49] The first Imamate reached its peak power in the ninth A.D. century.[43] The Imamate established a maritime empire whose fleet controlled the Gulf during the time when trade with the Abbasid Dynasty, the East and Africa flourished.[50] The authority of the Imams started to decline due to power struggles, the constant interventions of Abbasid and the rise of the Seljuk Empire.[51][48]

Nabhani dynasty

During the 11th and 12th centuries, Oman was controlled by the Seljuk Empire. They were expelled in 1154, when the Nabhani dynasty came to power.[51] The Nabhanis ruled as muluk, or kings, while the Imams were reduced to largely symbolic significance. The capital of the dynasty was Bahla.[52] The Banu Nabhan controlled the trade in frankincense on the overland route via Sohar to the Yabrin oasis, and then north to Bahrain, Baghdad and Damascus.[53] The mango-tree was introduced to Oman during the time of Nabhani dynasty, by ElFellah bin Muhsin.[24][54] The Nabhani dynasty started to deteriorate in 1507 when Portuguese colonisers captured the coastal city of Muscat, and gradually extended their control along the coast up to Sohar in the north and down to Sur in the southeast.[55] Other historians argue that the Nabhani dynasty ended earlier in A.D. 1435 when conflicts between the dynasty and Alhinawis arose, which led to the restoration of the elective Imamate.[24]

Portuguese colonisation

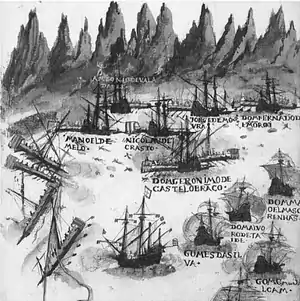

A decade after Vasco da Gama's successful voyage around the Cape of Good Hope and to India in 1497–98, the Portuguese arrived in Oman and occupied Muscat for a 143-year period, from 1507 to 1650. In need of an outpost to protect their sea lanes, the Portuguese built up and fortified the city, where remnants of their colonial architectural style still exist. An Ottoman fleet captured Muscat in 1552, during the fight for control of the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean.[56] Several Oman cities were colonized in the early 16th century, to control the entrances of the Persian Gulf and trade in the region. It was part of a web of fortresses that the Portuguese had in the region, from Basra to Hormuz. Several cities were drawn in the 17th century as it appears in the António Bocarro Book of fortress.[57]

Yaruba dynasty

The Ottoman Turks temporarily captured Muscat from the Portuguese in 1581 and held it until 1588. During the 17th century, the Omanis were reunited by the Yaruba Imams. Nasir bin Murshid became the first Yaarubah Imam in 1624, when he was elected in Rustak. Nasir's energy and perseverance is believed to have earned him the election.[59] Imam Nasir succeeded in the 1650s to force the Portuguese colonisers out of Oman.[43] The Omanis over time established a maritime empire that later expelled the Portuguese from East Africa, which became an Omani colony. To capture Zanzibar Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, pressed down the Swahili Coast. A major obstacle to his progress was Fort Jesus, housing the garrison of a Portuguese settlement at Mombasa. After a two-year siege, the fort fell to Saif bin Sultan in 1698. Thereafter the Omanis easily ejected the Portuguese from other African coastal regions including Kilwa and Pemba. Saif bin Sultan occupied Bahrain in 1700. Qeshm was captured in 1720.[50][60] The rivalry within the house of Yaruba over power after the death of Imam Sultan in 1718 weakened the dynasty. With the power of the Yaruba Dynasty dwindling, Imam Saif bin Sultan II eventually asked for help against his rivals from Nader Shah of Persia. A Persian force arrived in March 1737 to aid Saif. From their base at Julfar, the Persian forces eventually rebelled against the Yaruba in 1743. The Persian empire then colonised Oman for a short period until 1747.[43][61]

18th and 19th centuries

After the decolonization of Oman from the Persians, Ahmed bin Sa'id Albusaidi in 1749 became the elected Imam of Oman, with Rustaq serving as the capital. Since the Yaruba dynasty, the Omanis kept the elective system but, provided that the person is deemed qualified, gave preference to a member of the ruling family.[62] Following Imam Ahmed's death in 1783, his son, Said bin Ahmed became the elected Imam. His son, Seyyid Hamed bin Said, overthrew the representative of the Imam in Muscat and obtained the possession of Muscat fortress. Hamed ruled as "Seyyid". Afterwards, Seyyid Sultan bin Ahmed, the uncle of Seyyid Hamed, took over power. Seyyid Said bin Sultan succeeded Sultan bin Ahmed.[63][64] During the entire 19th century, in addition to Imam Said bin Ahmed who retained the title until he died in 1803, Azzan bin Qais was the only elected Imam of Oman. His rule started in 1868. However, the British refused to accept Imam Azzan as a ruler. The refusal played an instrumental role in deposing Imam Azzan in 1871 by a sultan who Britain deemed to be more acceptable.[65]

Oman's Imam Sultan, defeated ruler of Muscat, was granted sovereignty over Gwadar, an area of modern-day Pakistan. This coastal city is located in the Makran region of what is now the far southwestern corner of Pakistan, near the present-day border of Iran, at the mouth of the Gulf of Oman.[note 1][66] After regaining control of Muscat, this sovereignty was continued via an appointed wali ("governor").s

British de facto colonisation

The British empire was keen to dominate southeast Arabia to stifle the growing power of other European states and to curb the Omani maritime power that grew during the 17th century.[67][50] The British empire over time, starting from the late 18th century, began to establish a series of treaties with the sultans with the objective of advancing British political and economic interest in Muscat, while granting the sultans military protection.[50][67] In 1798, the first treaty between the British East India Company and Albusaidi family was signed by Sultan bin Ahmed. The treaty was to block commercial competition of the French and the Dutch as well as obtain a concession to build a British factory at Bandar Abbas.[68][43][69] A second treaty was signed in 1800, which stipulated that a British representative shall reside at the port of Muscat and manage all external affairs with other states.[69] The British influence that grew during the nineteenth century over Muscat weakened the Omani Empire.[58]

In 1854, a deed of cession of the Omani Kuria Muria islands to Britain was signed by the sultan of Muscat and the British government.[71] The British government achieved predominating control over Muscat, which, for the most part, impeded competition from other nations.[72] Between 1862 and 1892, the Political Residents, Lewis Pelly and Edward Ross, played an instrumental role in securing British supremacy over the Persian Gulf and Muscat by a system of indirect governance.[65] By the end of the 19th century, the British influence increased to the point that the sultans became heavily dependent on British loans and signed declarations to consult the British government on all important matters.[67][73][74][75] The Sultanate thus became a de facto British colony.[74][76]

Zanzibar was a valuable property as the main slave market of the Swahili Coast, and became an increasingly important part of the Omani empire, a fact reflected by the decision of the 19th century sultan of Muscat, Sa'id ibn Sultan, to make it his main place of residence in 1837. Sa'id built impressive palaces and gardens in Zanzibar. Rivalry between his two sons was resolved, with the help of forceful British diplomacy, when one of them, Majid, succeeded to Zanzibar and to the many regions claimed by the family on the Swahili Coast. The other son, Thuwaini, inherited Muscat and Oman. Zanzibar influences in the Comoros archipelago in the Indian Ocean indirectly introduced Omani customs to the Comorian culture. These influences include clothing traditions and wedding ceremonies.[77] In 1856, under British direction, Zanzibar and Muscat became two different sultanates.[60]

Treaty of Seeb

The Al Hajar Mountains, of which the Jebel Akhdar is a part, separate the country into two distinct regions: the interior, known as Oman, and the coastal area dominated by the capital, Muscat.[78] The British imperial development over Muscat and Oman during the 19th century led to the renewed revival of the Imamate cause in the interior of Oman, which has appeared in cycles for more than 1,200 years in Oman.[50] The British Political Agent, who resided in Muscat, owed the alienation of the interior of Oman to the vast influence of the British government over Muscat, which he described as being completely self-interested and without any regard to the social and political conditions of the locals.[79] In 1913, Imam Salim Alkharusi instigated an anti-Muscat rebellion that lasted until 1920 when the Imamate established peace with the Sultanate by signing the Treaty of Seeb.The treaty was brokered by Britain, which had no economic interest in the interior of Oman during that point of time. The treaty granted autonomous rule to the Imamate in the interior of Oman and recognized the sovereignty of the coast of Oman, the Sultanate of Muscat.[67][80][81][82] In 1920, Imam Salim Alkharusi died and Muhammad Alkhalili was elected.[43]

On 10 January 1923, an agreement between the Sultanate and the British government was signed in which the Sultanate had to consult with the British political agent residing in Muscat and obtain the approval of the High Government of India to extract oil in the Sultanate.[83] On 31 July 1928, the Red Line Agreement was signed between Anglo-Persian Company (later renamed British Petroleum), Royal Dutch/Shell, Compagnie Française des Pétroles (later renamed Total), Near East Development Corporation (later renamed ExxonMobil) and Calouste Gulbenkian (an Armenian businessman) to collectively produce oil in the post-Ottoman Empire region, which included the Arabian peninsula, with each of the four major companies holding 23.75 percent of the shares while Calouste Gulbenkian held the remaining 5 percent shares. The agreement stipulated that none of the signatories was allowed to pursue the establishment of oil concessions within the agreed on area without including all other stakeholders. In 1929, the members of the agreement established Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC).[84] On 13 November 1931, Sultan Taimur bin Faisal abdicated.[85]

Reign of Sultan Said (1932–1970)

Said bin Taimur became the sultan of Muscat officially on 10 February 1932. The rule of sultan Said bin Taimur, who was backed by the British government, was characterized as being feudal, reactionary and isolationist.[82][50][74][86] The British government maintained vast administrative control over the Sultanate as the defence secretary and chief of intelligence, chief adviser to the sultan and all ministers except for one were British.[74][87] In 1937, an agreement between the sultan and Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), a consortium of oil companies that was 23.75% British owned, was signed to grant oil concessions to IPC. After failing to discover oil in the Sultanate, IPC was intensely interested in some promising geological formations near Fahud, an area located within the Imamate. IPC offered financial support to the sultan to raise an armed force against any potential resistance by the Imamate.[88][89]

In 1955, the exclave coastal Makran strip acceded to Pakistan and was made a district of its Balochistan province, while Gwadar remained in Oman. On 8 September 1958, Pakistan purchased the Gwadar enclave from Oman for US$3 million.[note 2][90] Gwadar then became a tehsil in the Makran district.

Jebel Akhdar War

Sultan Said bin Taimur expressed his interest to the British government in occupying the Imamate right after the death of Imam Alkhalili and take advantage of potential instability that may occur within the Imamate when elections were due.[91] The British political agent in Muscat believed that the only method of gaining access to the oil reserves in the interior was by assisting the sultan in taking over the Imamate.[92] In 1946, the British government offered arms and ammunition, auxiliary supplies and officers to prepare the sultan to attack the interior of Oman.[93] In May 1954, Imam Alkhalili died and Ghalib Alhinai became the elected Imam of the Imamate of Oman.[94] Relations between the sultan of Muscat, Said bin Taimur, and Imam Ghalib Alhinai frayed over their dispute about oil concessions. Under the terms of the 1920 treaty of Seeb, the Sultan, backed by the British government, claimed all dealings with the oil company as his prerogative. The Imam, on the other hand, claimed that since the oil was in the Imamate territory, anything concerning it was an internal matter.[78]

In December 1955, sultan Said bin Taimur sent troops of the Muscat and Oman Field Force to occupy the main centres in Oman, including Nizwa, the capital of the Imamate of Oman, and Ibri.[80][95] The Omanis in the interior led by Imam Ghalib Alhinai, Talib Alhinai, the brother of the Imam and the Wali (governor) of Rustaq, and Suleiman bin Hamyar, who was the Wali (governor) of Jebel Akhdar, defended the Imamate of Oman in the Jebel Akhdar War against British-backed attacks by the Sultanate. In July 1957, the Sultan's forces were withdrawing, but they were repeatedly ambushed, sustaining heavy casualties.[80] Sultan Said, however, with the intervention of British infantry (two companies of the Cameronians), armoured car detachments from the British Army and RAF aircraft, was able to suppress the rebellion.[96] The Imamate's forces retreated to the inaccessible Jebel Akhdar.[96][88]

Colonel David Smiley, who had been seconded to organise the Sultan's Armed Forces, managed to isolate the mountain in autumn 1958 and found a route to the plateau from Wadi Bani Kharus.[97] On 4 August 1957, the British Foreign Secretary gave the approval to carry out air strikes without prior warning to the locals residing in the interior of Oman.[86] Between July and December 1958, the British RAF made 1,635 raids, dropping 1,094 tons and firing 900 rockets at the interior of Oman targeting insurgents, mountain top villages, water channels and crops.[74][86] On 27 January 1959, the Sultanate's forces occupied the mountain in a surprise operation.[97] Ghalib, Talib and Sulaiman managed to escape to Saudi Arabia, where the Imamate's cause was promoted until the 1970s.[97] The interior of Oman presented the case of Oman to the Arab League and the United Nations.[98][99] On 11 December 1963, the UN General Assembly decided to establish an Ad-Hoc Committee on Oman to study the 'Question of Oman' and report back to the General Assembly.[100] The UN General Assembly adopted the 'Question of Oman' resolution in 1965, 1966 and again in 1967 that called upon the British government to cease all repressive action against the locals, end British control over Oman and reaffirmed the inalienable right of the Omani people to self-determination and independence.[101][102][76][103][104][105]

Dhofar Rebellion

Oil reserves in Dhofar were discovered in 1964 and extraction began in 1967. In the Dhofar Rebellion, which began in 1965, pro-Soviet forces were pitted against government troops. As the rebellion threatened the Sultan's control of Dhofar, Sultan Said bin Taimur was deposed in a bloodless coup (1970) by his son Qaboos bin Said, who expanded the Sultan of Oman's Armed Forces, modernised the state's administration and introduced social reforms. The uprising was finally put down in 1975 with the help of forces from Iran, Jordan, Pakistan and the British Royal Air Force, army and Special Air Service.

Reign of Sultan Qaboos (1970–2020)

.jpg.webp)

After deposing his father in 1970, Sultan Qaboos opened up the country, embarked on economic reforms, and followed a policy of modernisation marked by increased spending on health, education and welfare.[106] Slavery, once a cornerstone of the country's trade and development, was outlawed in 1970.[77]

In 1981, Oman became a founding member of the six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council. Political reforms were eventually introduced. Historically, voters had been chosen from among tribal leaders, intellectuals and businessmen. In 1997, Sultan Qaboos decreed that women could vote for, and stand for election to, the Majlis al-Shura, the Consultative Assembly of Oman. Two women were duly elected to the body.

In 2002, voting rights were extended to all citizens over the age of 21, and the first elections to the Consultative Assembly under the new rules were held in 2003. In 2004, the Sultan appointed Oman's first female minister with portfolio, Sheikha Aisha bint Khalfan bin Jameel al-Sayabiyah. She was appointed to the post of National Authority for Industrial Craftsmanship, an office that attempts to preserve and promote Oman's traditional crafts and stimulate industry.[107] Despite these changes, there was little change to the actual political makeup of the government. The Sultan continued to rule by decree. Nearly 100 suspected Islamists were arrested in 2005 and 31 people were convicted of trying to overthrow the government. They were ultimately pardoned in June of the same year.[8]

Inspired by the Arab Spring uprisings that were taking place throughout the region, protests occurred in Oman during the early months of 2011. While they did not call for the ousting of the regime, demonstrators demanded political reforms, improved living conditions and the creation of more jobs. They were dispersed by riot police in February 2011. Sultan Qaboos reacted by promising jobs and benefits. In October 2011, elections were held to the Consultative Assembly, to which Sultan Qaboos promised greater powers. The following year, the government began a crackdown on internet criticism. In September 2012, trials began of 'activists' accused of posting "abusive and provocative" criticism of the government online. Six were given jail terms of 12–18 months and fines of around $2,500 each.[108]

Qaboos died on 10 January 2020, and the government declared three days of national mourning. He was buried the next day.[109]

Reign of Sultan Haitham (2020–present)

On 11 January 2020, Qaboos was succeeded by his first cousin Sultan Haitham bin Tariq Al Said.[110]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

Oman lies between latitudes 16° and 28° N, and longitudes 52° and 60° E. A vast gravel desert plain covers most of central Oman, with mountain ranges along the north (Al Hajar Mountains) and southeast coast (Qara or Dhofar Mountains),[111][112] where the country's main cities are located: the capital city Muscat, Sohar and Sur in the north, and Salalah in the south. Oman's climate is hot and dry in the interior and humid along the coast. During past epochs, Oman was covered by ocean, as evidenced by the large numbers of fossilized shells found in areas of the desert away from the modern coastline.

The peninsula of Musandam (Musandem) exclave, which is strategically located on the Strait of Hormuz, is separated from the rest of Oman by the United Arab Emirates.[113] The series of small towns known collectively as Dibba are the gateway to the Musandam peninsula on land and the fishing villages of Musandam by sea, with boats available for hire at Khasab for trips into the Musandam peninsula by sea.

Oman's other exclave, inside UAE territory, known as Madha, located halfway between the Musandam Peninsula and the main body of Oman,[113] is part of the Musandam governorate, covering approximately 75 km2 (29 sq mi). Madha's boundary was settled in 1969, with the north-east corner of Madha barely 10 m (32.8 ft) from the Fujairah road. Within the Madha exclave is a UAE enclave called Nahwa, belonging to the Emirate of Sharjah, situated about 8 km (5 mi) along a dirt track west of the town of New Madha, and consisting of about forty houses with a clinic and telephone exchange.[114]

The central desert of Oman is an important source of meteorites for scientific analysis.[115]

Climate

Like the rest of the Persian Gulf, Oman generally has one of the hottest climates in the world—with summer temperatures in Muscat and northern Oman averaging 30 to 40 °C (86.0 to 104.0 °F).[116] Oman receives little rainfall, with annual rainfall in Muscat averaging 100 mm (3.9 in), occurring mostly in January. In the south, the Dhofar Mountains area near Salalah has a tropical-like climate and receives seasonal rainfall from late June to late September as a result of monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean, leaving the summer air saturated with cool moisture and heavy fog.[117] Summer temperatures in Salalah range from 20 to 30 °C (68.0 to 86.0 °F)—relatively cool compared to northern Oman.[118]

The mountain areas receive more rainfall, and annual rainfall on the higher parts of the Jabal Akhdar probably exceeds 400 mm (15.7 in).[119] Low temperatures in the mountainous areas leads to snow cover once every few years.[120] Some parts of the coast, particularly near the island of Masirah, sometimes receive no rain at all within the course of a year. The climate is generally very hot, with temperatures reaching around 54 °C (129.2 °F) (peak) in the hot season, from May to September.[121]

On 26 June 2018 the city of Qurayyat set the record for highest minimum temperature in a 24-hour period, 42.6 °C (108.7 °F).[122]

Flora and fauna

Desert shrub and desert grass, common to southern Arabia, are found in Oman, but vegetation is sparse in the interior plateau, which is largely gravel desert. The greater monsoon rainfall in Dhofar and the mountains makes the growth there more luxuriant during summer; coconut palms grow plentifully on the coastal plains of Dhofar and frankincense is produced in the hills, with abundant oleander and varieties of acacia. The Al Hajar Mountains are a distinct ecoregion, the highest points in eastern Arabia with wildlife including the Arabian tahr.

Indigenous mammals include the leopard, hyena, fox, wolf, hare, oryx and ibex. Birds include the vulture, eagle, stork, bustard, Arabian partridge, bee eater, falcon and sunbird. In 2001, Oman had nine endangered species of mammals, five endangered types of birds, and nineteen threatened plant species. Decrees have been passed to protect endangered species, including the Arabian leopard, Arabian oryx, mountain gazelle, goitered gazelle, Arabian tahr, green sea turtle, hawksbill turtle and olive ridley turtle. However, the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary is the first site ever to be deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List, following the government's 2007 decision to reduce the site's area by 90% in order to clear the way for oil prospectors.[123]

In recent years, Oman has become one of the newer hot spots for whale watching, highlighting the critically endangered Arabian humpback whale, the most isolated and only non-migratory population in the world, sperm whales and pygmy blue whales.[124]

Environment

Drought and limited rainfall contribute to shortages in the nation's water supply. Maintaining an adequate supply of water for agricultural and domestic use is one of Oman's most pressing environmental problems, with limited renewable water resources. 94% of available water is used in farming and 2% for industrial activity, with the majority sourced from fossil water in the desert areas and spring water in hills and mountains.

In terms of climate action, major challenges remain to be solved, per the United Nations Sustainable Development 2019 index. The CO

2 emissions from energy (tCO

2/capita) and CO

2 emissions embodied in fossil fuel exports (kg per capita) rates are very high, while imported CO

2 emissions (tCO

2/capita) and people affected by climate-related disasters (per 100,000 people) rates are low.[125]

Drinking water is available throughout Oman, either piped or delivered. The soil in coastal plains, such as Salalah, have shown increased levels of salinity, due to over exploitation of ground water and encroachment by seawater on the water table. Pollution of beaches and other coastal areas by oil tanker traffic through the Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman is also a persistent concern.[126]

Local and national entities have noted unethical treatment of animals in Oman. In particular, stray dogs (and to a lesser extent, stray cats) are often the victims of torture, abuse or neglect.[127] The only approved method of decreasing the stray dog population is shooting by police officers. The Oman government has refused to implement a spay and neuter programme or create any animal shelters in the country. Cats, while seen as more acceptable than dogs, are viewed as pests and frequently die of starvation or illness.[128][129]

In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked Oman as the least polluted country in the Arab world, with a score of 37.7 in the pollution index. The country ranked 112th in Asia among the list of highest polluted countries.[130]

Politics

Oman is a unitary state and an absolute monarchy,[131] in which all legislative, executive and judiciary power ultimately rests in the hands of the hereditary Sultan. Consequently, Freedom House has routinely rated the country "Not Free".[132]

The sultan is the head of state and directly controls the foreign affairs and defence portfolios.[133] He has absolute power and issues laws by decree.[134][135]

Legal system

Oman is an absolute monarchy, with the Sultan's word having the force of law. The judiciary branch is subordinate to the Sultan. According to Oman's constitution, Sharia law is one of the sources of legislation. Sharia court departments within the civil court system are responsible for family-law matters, such as divorce and inheritance.

Oman does not have separation of powers.[11] All power is concentrated in the Sultan,[11] who is also chief of staff of the armed forces, Minister of Defence, Minister of Foreign Affairs and chairman of the Central Bank.[11] All legislation since 1970 has been promulgated through royal decrees, including the 1996 Basic Law.[11] The Sultan appoints judges, and can grant pardons and commute sentences.[11] The Sultan's authority is inviolable and the Sultan expects total subordination to his will.[11]

The administration of justice is highly personalized, with limited due process protections, especially in political and security-related cases.[136] The Basic Statute of the State[137] is supposedly the cornerstone of the Omani legal system and it operates as a constitution for the country. The Basic Statute was issued in 1996 and thus far has only been amended once, in 2011,[138] in response to protests.

Though Oman's legal code theoretically protects civil liberties and personal freedoms, both are regularly ignored by the regime.[11] Women and children face legal discrimination in many areas.[11] Women are excluded from certain state benefits, such as housing loans, and are refused equal rights under the personal status law.[11] Women also experience restrictions on their self-determination in respect to health and reproductive rights.[11]

The Omani legislature is the bicameral Council of Oman, consisting of an upper chamber, the Council of State (Majlis ad-Dawlah) and a lower chamber, the Consultative Council (Majlis ash-Shoura).[139] Political parties are banned.[135] The upper chamber has 71 members, appointed by the Sultan from among prominent Omanis; it has only advisory powers.[140] The 84 members of the Consultative Council are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms, but the Sultan makes the final selections and can negotiate the election results.[140] The members are appointed for three-year terms, which may be renewed once.[139] The last elections were held on 27 October 2019, and the next is due in October 2023. Oman's national anthem, As-Salam as-Sultani is dedicated to former Sultan Qaboos.

Foreign policy

Since 1970, Oman has pursued a moderate foreign policy, and has expanded its diplomatic relations dramatically. Oman is among the very few Arab countries that have maintained friendly ties with Iran.[141][142] WikiLeaks disclosed US diplomatic cables which state that Oman helped free British sailors captured by Iran's navy in 2007.[143] The same cables also portray the Omani government as wishing to maintain cordial relations with Iran, and as having consistently resisted US diplomatic pressure to adopt a sterner stance.[144][145][146] Yusuf bin Alawi bin Abdullah is the Sultanate's Minister Responsible for Foreign Affairs.

Oman allowed the British Royal Navy and Indian Navy access to the port facilities of Al Duqm Port & Drydock.[147]

Military

SIPRI's estimation of Oman's military and security expenditure as a percentage of GDP in 2019 was 8.8 percent,[148] making it the world's highest rate in that year, higher than Saudi Arabia (8 percent).[149] Oman's on-average military spending as a percentage of GDP between 2016 and 2018 was around 10 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 2.2 percent.[150]

Oman's military manpower totalled 44,100 in 2006, including 25,000 men in the army, 4,200 sailors in the navy, and an air force with 4,100 personnel. The Royal Household maintained 5,000 Guards, 1,000 in Special Forces, 150 sailors in the Royal Yacht fleet, and 250 pilots and ground personnel in the Royal Flight squadrons. Oman also maintains a modestly sized paramilitary force of 4,400 men.[151]

The Royal Army of Oman had 25,000 active personnel in 2006, plus a small contingent of Royal Household troops. Despite a comparative large military spending, it has been relatively slow to modernise its forces. Oman has a relatively limited number of tanks, including 6 M60A1, 73 M60A3 and 38 Challenger 2 main battle tanks, as well as 37 aging Scorpion light tanks.[151]

The Royal Air Force of Oman has approximately 4,100 men, with only 36 combat aircraft and no armed helicopters. Combat aircraft include 20 aging Jaguars, 12 Hawk Mk 203s, 4 Hawk Mk 103s and 12 PC-9 turboprop trainers with a limited combat capability. It has one squadron of 12 F-16C/D aircraft. Oman also has 4 A202-18 Bravos and 8 MFI-17B Mushshaqs.[151]

The Royal Navy of Oman had 4,200 men in 2000, and is headquartered at Seeb. It has bases at Ahwi, Ghanam Island, Mussandam and Salalah. In 2006, Oman had 10 surface combat vessels. These included two 1,450-ton Qahir class corvettes, and 8 ocean-going patrol boats. The Omani Navy had one 2,500-ton Nasr al Bahr class LSL (240 troops, 7 tanks) with a helicopter deck. Oman also had at least four landing craft.[151] Oman ordered three Khareef class corvettes from the VT Group for £400 million in 2007. They were built at Portsmouth.[152] In 2010 Oman spent US$4.074 billion on military expenditures, 8.5% of the gross domestic product.[153] The sultanate has a long history of association with the British military and defence industry.[154] According to SIPRI, Oman was the 23rd largest arms importer from 2012 to 2016.[155]

Human rights

Homosexual acts are illegal in Oman.[156] The practice of torture is widespread in Oman state penal institutions and has become the state's typical reaction to independent political expression.[157][158] Torture methods in use in Oman include mock execution, beating, hooding, solitary confinement, subjection to extremes of temperature and to constant noise, abuse and humiliation.[157] There have been numerous reports of torture and other inhumane forms of punishment perpetrated by Omani security forces on protesters and detainees.[159] Several prisoners detained in 2012 complained of sleep deprivation, extreme temperatures and solitary confinement.[160] Omani authorities kept Sultan al-Saadi, a social media activist, in solitary confinement, denied him access to his lawyer and family, forced him to wear a black bag over his head whenever he left his cell, including when using the toilet, and told him his family had "forsaken" him and asked for him to be imprisoned.[160]

The Omani government decides who can or cannot be a journalist and this permission can be withdrawn at any time.[162] Censorship and self-censorship are a constant factor.[162] Omanis have limited access to political information through the media.[163] Access to news and information can be problematic: journalists have to be content with news compiled by the official news agency on some issues.[162] Through a decree by the Sultan, the government has now extended its control over the media to blogs and other websites.[162] Omanis cannot hold a public meeting without the government's approval.[162] Omanis who want to set up a non-governmental organisation of any kind need a licence.[162] To get a licence, they have to demonstrate that the organisation is "for legitimate objectives" and not "inimical to the social order".[162] The Omani government does not permit the formation of independent civil society associations.[159] Human Rights Watch issued on 2016, that an Omani court sentenced three journalists to prison and ordered the permanent closure of their newspaper, over an article that alleged corruption in the judiciary.[164]

The law prohibits criticism of the Sultan and government in any form or medium.[162] Oman's police do not need search warrants to enter people's homes.[162] The law does not provide citizens with the right to change their government.[162] The Sultan retains ultimate authority on all foreign and domestic issues.[162] Government officials are not subject to financial disclosure laws.[162] Libel laws and concerns for national security have been used to suppress criticism of government figures and politically objectionable views.[162] Publication of books is limited and the government restricts their importation and distribution, as with other media products.[162]

Merely mentioning the existence of such restrictions can land Omanis in trouble.[162] In 2009, a web publisher was fined and given a suspended jail sentence for revealing that a supposedly live TV programme was actually pre-recorded to eliminate any criticisms of the government.[162]

Faced with so many restrictions, Omanis have resorted to unconventional methods for expressing their views.[162] Omanis sometimes use donkeys to express their views.[162] Writing about Gulf rulers in 2001, Dale Eickelman observed: "Only in Oman has the occasional donkey… been used as a mobile billboard to express anti-regime sentiments. There is no way in which police can maintain dignity in seizing and destroying a donkey on whose flank a political message has been inscribed."[162] Some people have been arrested for allegedly spreading fake news about the COVID-19 pandemic in Oman.[165]

Omani citizens need government permission to marry foreigners.[160] The Ministry of Interior requires Omani citizens to obtain permission to marry foreigners (except nationals of GCC countries); permission is not automatically granted.[160] Citizen marriage to a foreigner abroad without ministry approval may result in denial of entry for the foreign spouse at the border and preclude children from claiming citizenship rights.[160] It also may result in a bar from government employment and a fine of 2,000 rials ($5,200).[160]

.jpg.webp)

In August 2014, The Omani writer and human rights defender Mohammed Alfazari, the founder and editor-in-chief of the e-magazine Mowatin "Citizen", disappeared after going to the police station in the Al-Qurum district of Muscat.[166] For several months the Omani government denied his detention and refused to disclose information about his whereabouts or condition.[166] On 17 July 2015, Alfazari left Oman seeking political asylum in UK after a travel ban was issued against him without providing any reasons and after his official documents including his national ID and passport were confiscated for more than 8 months.[167] There were more reports of politically motivated disappearances in the country.[160] In 2012, armed security forces arrested Sultan al-Saadi, a social media activist.[160] According to reports, authorities detained him at an unknown location for one month for comments he posted online critical of the government.[160] Authorities previously arrested al-Saadi in 2011 for participating in protests and again in 2012 for posting comments online deemed insulting to Sultan Qaboos.[160] In May 2012 security forces detained Ismael al-Meqbali, Habiba al-Hinai and Yaqoub al-Kharusi, human rights activists who were visiting striking oil workers.[160] Authorities released al-Hinai and al-Kharusi shortly after their detention but did not inform al-Meqbali's friends and family of his whereabouts for weeks.[160] Authorities pardoned al-Meqbali in March.[160] In December 2013, a Yemeni national disappeared in Oman after he was arrested at a checkpoint in Dhofar Governorate.[168] Omani authorities refuse to acknowledge his detention.[168] His whereabouts and condition remain unknown.[168]

The National Human Rights Commission, established in 2008, is not independent from the regime.[11] It is chaired by the former deputy inspector general of Police and Customs and its members are appointed by royal decree.[11] In June 2012, one of its members requested that she be relieved of her duties because she disagreed with a statement made by the Commission justifying the arrest of intellectuals and bloggers and the restriction of freedom of expression in the name of respect for "the principles of religion and customs of the country".[11]

Since the beginning of the "Omani Spring" in January 2011, a number of serious violations of civil rights have been reported, amounting to a critical deterioration of the human rights situation.[11] Prisons are inaccessible to independent monitors.[11] Members of the independent Omani Group of Human Rights have been harassed, arrested and sentenced to jail. There have been numerous testimonies of torture and other inhumane forms of punishment perpetrated by security forces on protesters and detainees.[11] The detainees were all peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression and assembly.[11] Although authorities must obtain court orders to hold suspects in pre-trial detention, they do not regularly do this.[11] The penal code was amended in October 2011 to allow the arrest and detention of individuals without an arrest warrant from public prosecutors.[11]

In January 2014, Omani intelligence agents arrested a Bahraini actor and handed him over to the Bahraini authorities on the same day of his arrest.[169] The actor has been subjected to a forced disappearance. His whereabouts and condition remain unknown.[169]

Migrant workers

The plight of domestic workers in Oman is a taboo subject.[170][171] In 2011, the Philippines government determined that out of all the countries in the Middle East, only Oman and Israel qualify as safe for Filipino migrants.[172] In 2012, it was reported that every 6 days, an Indian migrant in Oman commits suicide.[173][174] There has been a campaign urging authorities to check the migrant suicide rate.[175] In the 2014 Global Slavery Index, Oman is ranked No. 45 due to 26,000 people in slavery.[176][177] The descendants of servant tribes and slaves are victims of widespread discrimination.[159][178] Oman was one of the last countries to abolish slavery, in 1970.[171]

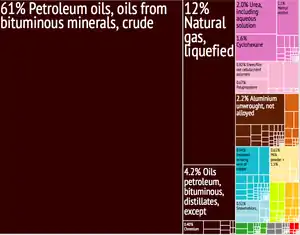

Economy

Oman's Basic Statute of the State expresses in Article 11 that the "national economy is based on justice and the principles of a free economy."[181] By regional standards, Oman has a relatively diversified economy, but remains dependent on oil exports. In terms of monetary value, mineral fuels accounted for 82.2 percent of total product exports in 2018.[182] Tourism is the fastest-growing industry in Oman. Other sources of income, agriculture and industry, are small in comparison and account for less than 1% of the country's exports, but diversification is seen as a priority by the government. Agriculture, often subsistence in its character, produces dates, limes, grains and vegetables, but with less than 1% of the country under cultivation, Oman is likely to remain a net importer of food.

Oman's socio-economic structure is described as being hyper-centralized rentier welfare state.[183] The largest 10 percent of corporations in Oman are the employers of almost 80 percent of Omani nationals in the private sector. Half of the private sector jobs are classified as elementary. One third of employed Omanis are in the private sector, while the remaining majority are in the public sector.[184] A hyper-centralized structure produces a monopoly-like economy, which hinders having a healthy competitive environment between businesses.[183]

Since a slump in oil prices in 1998, Oman has made active plans to diversify its economy and is placing a greater emphasis on other areas of industry, namely tourism and infrastructure. Oman had a 2020 Vision to diversify the economy established in 1995, which targeted a decrease in oil's share to less than 10 percent of GDP by 2020, but it was rendered obsolete in 2011. Oman then established 2040 Vision.[183]

A free-trade agreement with the United States took effect 1 January 2009, eliminated tariff barriers on all consumer and industrial products, and also provided strong protections for foreign businesses investing in Oman.[185] Tourism, another source of Oman's revenue, is on the rise.[186] A popular event is The Khareef Festival held in Salalah, Dhofar, which is 1,200 km from the capital city of Muscat, during the monsoon season (August) and is similar to Muscat Festival. During this latter event the mountains surrounding Salalah are popular with tourists as a result of the cool weather and lush greenery, rarely found anywhere else in Oman.[187]

Oman's foreign workers send an estimated US$10 billion annually to their home states in Asia and Africa, more than half of them earning a monthly wage of less than US$400.[188] The largest foreign community is from the Indian states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Gujarat and the Punjab,[189] representing more than half of entire workforce in Oman. Salaries for overseas workers are known to be less than for Omani nationals, though still from two to five times higher than for the equivalent job in India.[188]

In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI), total investments in 2017 exceeded US$24billion. The highest share of FDI went to the oil and gas sector, which represented around US$13billion (54.2 percent), followed by financial intermediation, which represented US$3.66billion (15.3 percent). FDI is dominated by the United Kingdom with an estimated value of US$11.56billion (48 percent), followed by the UAE USD 2.6billion (10.8 percent), followed by Kuwait USD 1.1billion (4.6 percent).[190]

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Oman by country as of 2017.[190]

Oman, in 2018 had a budget deficit of 32 percent of total revenue and a government debt to GDP of 47.5 percent.[191][192] Oman's military spending to GDP between 2016 and 2018 averaged 10 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 2.2 percent.[193] Oman's health spending to GDP between 2015 and 2016 averaged 4.3 percent, while the world's average during the same period was 10 percent.[194] Oman's research and development spending between 2016 and 2017 averaged 0.24 percent, which is significantly lower than the world's average (2.2 percent) during the same period.[195] Oman's government spending on education to GDP in 2016 was 6.11 percent, while the world's average was 4.8 percent (2015).[196]

| Type | Spending (% of GDP)[197][198][199][200] |

|---|---|

| military spending | 13.73 |

| education spending | 6.11 |

| health spending | 4.30 |

| research & development spending | 0.26 |

Oil and gas

Oman's proved reserves of petroleum total about 5.5 billion barrels, 25th largest in the world.[141] Oil is extracted and processed by Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), with proven oil reserves holding approximately steady, although oil production has been declining.[201][202] The Ministry of Oil and Gas is responsible for all oil and gas infrastructure and projects in Oman.[203] Following the 1970s energy crisis, Oman doubled their oil output between 1979 and 1985.[204]

In 2018, oil and gas represented 71 percent of the government's revenues.[191] In 2016, oil and gas share of the government's revenue represented 72 percent.[205] The government's reliance on oil and gas as a source of income dropped by 1 percent from 2016 to 2018. Oil and gas sector represented 30.1 percent of the nominal GDP in 2017.[206]

Between 2000 and 2007, production fell by more than 26%, from 972,000 to 714,800 barrels per day.[207] Production has recovered to 816,000 barrels in 2009, and 930,000 barrels per day in 2012.[207] Oman's natural gas reserves are estimated at 849.5 billion cubic metres, ranking 28th in the world, and production in 2008 was about 24 billion cubic metres per year.[141]

In September 2019, Oman was confirmed to become the first Middle Eastern country to host the International Gas Union Research Conference (IGRC 2020). This 16th iteration of the event will be held between 24 and 26 February 2020, in collaboration with Oman LNG, under the auspices of the Ministry of Oil and Gas.[208]

Tourism

Tourism in Oman has grown considerably recently, and it is expected to be one of the largest industries in the country.[209] The World Travel & Tourism Council stated that Oman is the fastest growing tourism destination in the Middle East.[210]

Tourism contributed 2.8 percent to the Omani GDP in 2016. It grew from RO 505 million (US$1.3 billion) in 2009 to RO 719 million (US$1.8 billion) in 2017 (+42.3 percent growth). Citizens of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), including Omanis who are residing outside of Oman, represent the highest ratio of all tourists visiting Oman, estimated to be 48 percent. The second highest number of visitors come from other Asian countries, who account for 17 percent of the total number of visitors.[211] A challenge to tourism development in Oman is the reliance on the government-owned firm, Omran, as a key actor to develop the tourism sector, which potentially creates a market barrier-to-entry of private-sector actors and a crowding out effect. Another key issue to the tourism sector is deepening the understanding of the ecosystem and biodiversity in Oman to guarantee their protection and preservation.[212]

.jpg.webp)

Oman has one of the most diverse environments in the Middle East with various tourist attractions and is particularly well known for adventure and cultural tourism.[186][213] Muscat, the capital of Oman, was named the second best city to visit in the world in 2012 by the travel guide publisher Lonely Planet.[214] Muscat also was chosen as the Capital of Arab Tourism of 2012.[215]

In November 2019, Oman made the rule of visa on arrival an exception and introduced the concept of e-visa for tourists from all nationalities. Under the new laws, visitors were required to apply for the visa in advance by visiting Oman's online government portal.[216]

Industry, innovation and infrastructure

In industry, innovation and infrastructure, Oman is still faced with "significant challenges", as per United Nations Sustainable Development Goals index, as of 2019. Oman has scored high on the rates of internet use, mobile broadband subscriptions, logistics performance and on the average of top 3 university rankings. Meanwhile, Oman scored low on the rate of scientific and technical publications and on research & development spending.[125] Oman's manufacturing value added to GDP rate in 2016 was 8.4 percent, which is lower than the average in the Arab world (9.8 percent) and world average (15.6 percent). In terms of research & development expenditures to GDP, Oman's share was on average 0.20 percent between 2011 and 2015, while the world's average during the same period was 2.11 percent.[217] The majority of firms in Oman operate in the oil and gas, construction and trade sectors.[212]

| Non-hydrocarbon GDP growth | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%)[218] | 4.8 | 6.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

Oman is refurbishing and expanding the ports infrastructure in Muscat, Duqm, Sohar and Salalah to expand tourism, local production and export shares. Oman is also expanding its downstream operations by constructing a refinery and petrochemical plant in Duqm with a 230,000 barrels per day capacity projected for completion by 2021.[190] The majority of industrial activity in Oman takes place in 8 industrial states and 4 free-zones. The industrial activity is mainly focused on mining-and-services, petrochemicals and construction materials.[212] The largest employers in the private-sector are the construction, wholesale-and-retail and manufacturing sectors, respectively. Construction accounts for nearly 48 percent of the total labour force, followed by wholesale-and-retail, which accounts for around 15 percent of total employment and manufacturing, which accounts for around 12 percent of employment in the private sector. The percentage of Omanis employed in the construction and manufacturing sectors is nevertheless low, as of 2011 statistics.[184]

Oman, as per Global Innovation Index (2019) report, scores "below expectations" in innovation relative to countries classified under high income.[219] Oman in 2019 ranked 80 out of 129 countries in innovation index, which takes into consideration factors, such as, political environment, education, infrastructure and business sophistication.[220] Innovation, technology-based growth and economic diversification are hindered by an economic growth that relies on infrastructure expansion, which heavily depends on a high percentage of 'low-skilled' and 'low-wage' foreign labour. Another challenge to innovation is the dutch disease phenomenon, which creates an oil and gas investment lock-in, while relying heavily on imported products and services in other sectors. Such a locked-in system hinders local business growth and global competitiveness in other sectors, and thus impedes economic diversification.[212] The inefficiences and bottlenecks in business operations that are a result of heavy dependence on natural resources and 'addiction' to imports in Oman suggest a 'factor-driven economy'.[184] A third hindrance to innovation in Oman is an economic structure that is heavily dependent on few large firms, while granting few opportunities for SMEs to enter the market, which impedes healthy market-share competition between firms.[212] The ratio of patent applications per million people was 0.35 in 2016 and the MENA region average was 1.50, while the 'high-income' countries' average was approximately 48.0 during the same year.[221]

| Patent Grants | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[222] | 2 | 4 | 6 | 14 |

Agriculture and fishing

Oman's fishing industry contributed 0.78 percent to the GDP in 2016. Fish exports between 2000 and 2016 grew from US$144 million to US$172 million (+19.4 percent). The main importer of Omani fish in 2016 was Vietnam, which imported almost US$80 million (46.5 percent) in value, and the second biggest importer was the United Arab Emirates, which imported around US$26 million (15 percent). The other main importers are Saudi Arabia, Brazil and China. Oman's consumption of fish is almost two times the world's average. The ratio of exported fish to total fish captured in tons fluctuated between 49 and 61 percent between 2006 and 2016. Omani strengths in the fishing industry comes from having a good market system, a long coastline (3,165 km) and wide water area. Oman, on the other hand, lacks sufficient infrastructure, research and development, quality and safety monitoring, together with a limited contribution by the fishing industry to GDP.[211]

Dates represent 80 percent of all fruit crop production. Further, date farms employ 50 percent of the total agricultural area in the country. Oman's estimated production of dates in 2016 is 350,000 tons, making it the 9th largest producer of dates. The vast majority of date production (75 percent) comes from only 10 cultivars. Oman's total export of dates was US$12.6 million in 2016, almost equivalent to Oman's total imported value of dates, which was US$11.3 million in 2016. The main importer is India (around 60 percent of all imports). Oman's date exports remained steady between 2006 and 2016. Oman is considered to have good infrastructure for date production and support provision to cultivation and marketing, but lacks innovation in farming and cultivation, industrial coordination in the supply chain and encounter high losses of unused dates.[211]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 456,000 | — |

| 1960 | 552,000 | +21.1% |

| 1970 | 724,000 | +31.2% |

| 1980 | 1,154,000 | +59.4% |

| 1990 | 1,812,000 | +57.0% |

| 2000 | 2,268,000 | +25.2% |

| 2010 | 3,041,000 | +34.1% |

| 2019 | 4,975,000 | +63.6% |

| source:[3][4] | ||

As of 2014, Oman's population is over 4 million, with 2.23 million Omani nationals and 1.76 million expatriates.[223] The total fertility rate in 2011 was estimated at 3.70.[224] Oman has a very young population, with 43 percent of its inhabitants under the age of 15. Nearly 50 percent of the population lives in Muscat and the Batinah coastal plain northwest of the capital. Omani people are predominantly of Arab, Baluchi and African origins.[141]

Omani society is largely tribal[178][225][226] and encompasses three major identities:[178] that of the tribe, the Ibadi faith and maritime trade.[178] The first two identities are closely tied to tradition and are especially prevalent in the interior of the country, owing to lengthy periods of isolation.[178] The third identity pertains mostly to Muscat and the coastal areas of Oman, and is reflected by business, trade,[178] and the diverse origins of many Omanis, who trace their roots to Baloch, Al-Lawatia, Persia and historical Omani Zanzibar.[227] Consequently, the third identity is generally seen to be more open and tolerant towards others,[178] and is often in tension with the more traditional and insular identities of the interior.[178]

Religion

Even though the Oman government does not keep statistics on religious affiliation, statistics from the US's Central Intelligence Agency state that adherents of Islam are in the majority at 85.9%, with Christians at 6.5%, Hindus at 5.5%, Buddhists at 0.8%, Jews less than 0.1%. Other religious affiliations have a proportion of 1% and the unaffiliated only 0.2%.

Most Omanis are Muslims, most of whom follow the Ibadi[229] school of Islam, followed by the Twelver school of Shia Islam, the Shafi`i school of Sunni Islam, and the Nizari Isma'ili school of Shia Islam.[230] Virtually all non-Muslims in Oman are foreign workers. Non-Muslim religious communities include various groups of Jains, Buddhists, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Jews, Hindus and Christians. Christian communities are centred in the major urban areas of Muscat, Sohar and Salalah. These include Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and various Protestant congregations, organising along linguistic and ethnic lines. More than 50 different Christian groups, fellowships and assemblies are active in the Muscat metropolitan area, formed by migrant workers from Southeast Asia.

There are also communities of ethnic Indian Hindus and Christians. There are also small Sikh[231] and Jewish[232] communities.

Languages

Arabic is the official language of Oman. It belongs to the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.[181] There are several dialects of Arabic spoken, all part of the Peninsular Arabic family: Dhofari Arabic (also known as Dhofari, Zofari) is spoken in Salalah and the surrounding coastal regions (the Dhofar Governorate);[233] Gulf Arabic is spoken in parts bordering the UAE; whereas Omani Arabic, distinct from the Gulf Arabic of eastern Arabia and Bahrain, is spoken in Central Oman, although with recent oil wealth and mobility has spread over other parts of the Sultanate.

According to the CIA, besides Arabic, English, Baluchi (Southern Baluchi), Urdu and various Indian languages are the main languages spoken in Oman.[141] English is widely spoken in the business community and is taught at school from an early age. Almost all signs and writings appear in both Arabic and English at tourist sites.[186] Baluchi is the mother tongue of the Baloch people from Balochistan in western Pakistan, eastern Iran and southern Afghanistan. It is also used by some descendants of Sindhi sailors.[234] A significant number of residents also speak Urdu, due to the influx of Pakistani migrants during the late 1980s and 1990s. Additionally, Swahili is widely spoken in the country due to the historical relations between Oman and Zanzibar.[10]

Prior to Islam, Central Oman lay outside of the core area of spoken Arabic. Possibly Old South Arabian speakers dwelled from the Al Batinah Region to Zafar, Yemen.[235] Rare Musnad inscriptions have come to light in central Oman and in the Emirate of Sharjah, but the script says nothing about the language which it conveys.[236] A bilingual text from the 3rd century BCE is written in Aramaic and in musnad Hasiatic, which mentions a 'king of Oman' (mālk mn ʿmn).[237] Today the Mehri language is limited in its distribution to the area around Salalah, in Zafar and westward into the Yemen. But until the 18th or 19th century it was spoken further north, perhaps into Central Oman.[238] Baluchi (Southern Baluchi) is widely spoken in Oman.[239] Endangered indigenous languages in Oman include Kumzari, Bathari, Harsusi, Hobyot, Jibbali and Mehri.[240] Omani Sign Language is the language of the deaf community. Oman was also the first Arab country in the Persian Gulf to have German taught as a second language.[241] The Bedouin Arabs, who reached eastern and southeastern Arabia in migrational waves—the latest in the 18th century, brought their language and rule including the ruling families of Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[242]

Education

| Rank | Economy | score |

|---|---|---|

| 56 | Albania | 0.62 |

| 55 | Malaysia | 0.62 |

| 54 | Oman | 0.62 |

| 53 | Turkey | 0.63 |

| 52 | Mauritius | 0.63 |

Oman scored high as of 2019 on the percentage of students who complete lower secondary school and on the literacy rate between the age of 15 and 24, 99.7 percent and 98.7 percent, respectively. However, Oman's net primary school enrollment rate in 2019, which is 94.1 percent, is rated as "challenges remain" by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG) standard. Oman's overall evaluation in quality of education, according to UNSDG, is 94.8 ("challenges remain") as of 2019.[125]

Oman's higher education produces a surplus in humanities and liberal arts, while it produces an insufficient number in technical and scientific fields and required skill-sets to meet the market demand.[212] Further, sufficient human capital creates a business environment that can compete with, partner or attract foreign firms. Accreditation standards and mechanisms with a quality control that focuses on input assessments, rather than output, are areas of improvement in Oman, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development 2014 report.[212] The transformation Index BTI 2018 report on Oman recommends that the education curriculum should focus more on the "promotion of personal initiative and critical perspective".[183]

The adult literacy rate in 2010 was 86.9%.[244] Before 1970, only three formal schools existed in the entire country, with fewer than 1,000 students. Since Sultan Qaboos' ascension to power in 1970, the government has given high priority to education to develop a domestic work force, which the government considers a vital factor in the country's economic and social progress. Today, there are over 1,000 state schools and about 650,000 students.

Oman's first university, Sultan Qaboos University, opened in 1986. The University of Nizwa is one of the fastest growing universities in Oman. Other post-secondary institutions in Oman include the Higher College of Technology and its six branches, six colleges of applied sciences (including a teachers' training college), a college of banking and financial studies, an institute of Sharia sciences, and several nursing institutes. Some 200 scholarships are awarded each year for study abroad.

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are Sultan Qaboos University (1678th worldwide), the Dhofar University (6011th) and the University of Nizwa (6093rd).[245]

Health

Since 2003, Oman's undernourished share of the population has dropped from 11.7 percent to 5.4 percent in 2016, but the rate remains high (double) the level of high-income economies (2.7 percent) in 2016.[246] The UNSDG targets zero hunger by 2030.[247] Oman's coverage of essential health services in 2015 was 77 percent, which is relatively higher than the world's average of approximately 54 percent during the same year, but lower than high-income economies' level (83 percent) in 2015.[248]

Since 1995, the percentage of Omani children who receive key vaccines has consistently been very high (above 99 percent). As for road incident death rates, Oman's rate has been decreasing since 1990, from 98.9 per 100,000 individuals to 47.1 per 100,000 in 2017, however, the rate remains significantly above average, which was 15.8 per 100,000 in 2017.[249] Oman's health spending to GDP between 2015 and 2016 averaged 4.3 percent, while the world's average during the same period averaged 10 percent.[194]

As for mortality due to air pollution (household and ambient air pollution), Oman's rate was 53.9 per 100,000 population as of 2016.[250]

Life expectancy at birth in Oman was estimated to be 76.1 years in 2010.[224] As of 2010, there were an estimated 2.1 physicians and 2.1 hospital beds per 1,000 people.[224] In 1993, 89% of the population had access to health care services. In 2000, 99% of the population had access to health care services. During the last three decades, the Oman health care system has demonstrated and reported great achievements in health care services and preventive and curative medicine. Oman has been making strides in health research too recently. Comprehensive research on the prevalence of skin diseases was performed in North batinah governorate.[251] In 2000, Oman's health system was ranked number 8 by the World Health Organization.[252]

Largest Cities

1) Muscat (Capital City of Oman), Muscat Governorate

3) Salalah, Dhofar Governorate

4) Bawshar, Muscat Governorate

5) Sohar, Al Batinah North Governorate

6) As Suwayq, Al Batinah North Governorate

7) Ibri, Az Zahirah Governorate

8) Saham, Al Batinah North Governorate

9) Rustaq, Al Batinah South Governorate

10) Buraimi, Al Buraimi Governorate

11) Nizwa, Ad Dakhiliyah Governorate

12) Sur, Southeastern Governorate

Culture

Outwardly, Oman shares many of the cultural characteristics of its Arab neighbours, particularly those in the Gulf Cooperation Council.[254] Despite these similarities, important factors make Oman unique in the Middle East.[254] These result as much from geography and history as from culture and economics.[254] The relatively recent and artificial nature of the state in Oman makes it difficult to describe a national culture;[254] however, sufficient cultural heterogeneity exists within its national boundaries to make Oman distinct from other Arab States of the Persian Gulf.[254] Oman's cultural diversity is greater than that of its Arab neighbours, given its historical expansion to the Swahili Coast and the Indian Ocean.[254]

Oman has a long tradition of shipbuilding, as maritime travel played a major role in the Omanis' ability to stay in contact with the civilisations of the ancient world. Sur was one of the most famous shipbuilding cities of the Indian Ocean. The Al Ghanja ship takes one whole year to build. Other types of Omani ship include As Sunbouq and Al Badan.[255]

In March 2016 archaeologists working off Al Hallaniyah Island identified a shipwreck believed to be that of the Esmeralda from Vasco da Gama's 1502–1503 fleet. The wreck was initially discovered in 1998. Later underwater excavations took place between 2013 and 2015 through a partnership between the Oman Ministry of Heritage and Culture and Blue Water Recoveries Ltd., a shipwreck recovery company. The vessel was identified through such artifacts as a "Portuguese coin minted for trade with India (one of only two coins of this type known to exist) and stone cannonballs engraved with what appear to be the initials of Vincente Sodré, da Gama's maternal uncle and the commander of the Esmeralda."[256]

Dress

The male national dress in Oman consists of the dishdasha, a simple, ankle-length, collarless gown with long sleeves.[167] Most frequently white in colour, the dishdasha may also appear in a variety of other colours. Its main adornment, a tassel (furakha) sewn into the neckline, can be impregnated with perfume.[257] Underneath the dishdasha, men wear a plain, wide strip of cloth wrapped around the body from the waist down. The most noted regional differences in dishdasha designs are the style with which they are embroidered, which varies according to age group.[167] On formal occasions a black or beige cloak called a bisht may cover the dishdasha. The embroidery edging the cloak is often in silver or gold thread and it is intricate in detail.[257]

Omani men wear two types of headdress:

- the ghutra, also called "Musar" a square piece of woven wool or cotton fabric of a single colour, decorated with various embroidered patterns.

- the kummah, a cap that is the head dress worn during leisure hours.[167]

Some men carry the assa, a stick, which can have practical uses or is simply used as an accessory during formal events. Omani men, on the whole, wear sandals on their feet.[257]