Optical stretcher

The Optical Stretcher is a dual-beam optical trap that is used for trapping and deforming ("stretching") micrometer-sized soft matter particles, such as biological cells in suspension. The forces used for trapping and deforming objects arise from photon momentum transfer on the surface of the objects, making the Optical Stretcher - unlike atomic force microscopy or micropipette aspiration - a tool for contact-free rheology measurements.

Overview

The trapping of micrometer-sized particles by two laser beams was first demonstrated by Arthur Ashkin in 1970,[1] before he developed the single-beam trap now known as optical tweezers. An advantage of the single-beam design is that no two laser beams need to be exactly adjusted to make their optical axes match. From the late 1980s on, optical tweezers have been used to trap and hold biological dielectrica, such as cells or viruses.[2]

However, in order to ensure trap stability, the single beam must be highly focused, with the particle trapped close to the focus point. Preventing damage done to biological material (see Opticution) by the high local light intensities in the focus limits the laser powers that one can use in the optical tweezers to a force range too low for rheology experiments, i.e. optical tweezers are suitable for trapping biological particles, but unsuitable for deforming them.

The optical stretcher, developed at the end of the 1990s by Jochen Guck and Josef A. Käs,[3] circumvents this problem by going back to the dual-beam design originally developed by Ashkin. This allows for weakly divergent laser, thus preventing damage done by localized light intensities and increasing the possible stretching forces to a range that is sufficient for the deformation of soft matter. The laser powers used in stretching cells are typically on the order of 1 W, generating stretch forces on the order of 100 pN. The resulting relative cellular deformation then usually lies in the range from 1% - 10%.

The optical stretcher has since been developed into a versatile biophysical tool used by many groups worldwide for contact-free, marker-free measurements of whole-cell rheology. Using automated setups, high throughput rates of more than 100 cells/hour have been achieved, allowing for statistical analysis of the data.

Applications

Cell mechanics and cell rheology play a crucial role in cellular development and also in many diseases. Due to its high throughput, the optical stretcher has in many biomechanical studies been the tool of choice to investigate the development of or changes in cell mechanics, among them studies on the development of cancer and stem cell differentiation.

An exemplary study in stem cell research sheds light on the process of cell differentiation: Hematopoietic stem cells residing in the bone marrow differentiate into different types of blood cells to produce human blood - i.e., red blood cells and different types of white blood cells. In this study, it was shown that the white blood cell types show different mechanical behaviour depending on their later physiological function and that these differences arise during the process of stem cell differentiation.[4]

Using the optical stretcher, it was also shown that cancerous cells differ significantly in their mechanical properties from their healthy counterparts.[5] The authors claim that the 'optical deformability' can be used as a biomechanical marker to distinguish cancerous from healthy cells, and even that higher stages of malignancy can be detected.

Optical stretcher setup

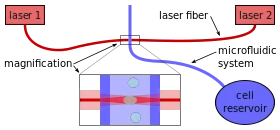

A typical optical stretcher setup consists of the following main parts:

- A microfluidic system. Typically, a suspension of single cells is pumped through a capillary. When a cell is in the right position to be trapped by the lasers, the flow must be stopped and the lasers turned on.

- Two opposing optical fibers from which the two laser beams emerge. One can either use two distinct lasers or one laser source and a beam splitter.

- A microscope used for imaging the trapped objects. As single cells are virtually transparent, often phase contrast microscopes are used, but depending on the desired measurement, for example using fluorescence microscopy is also an option. The deformation can be extracted from the images using an edge detection algorithm.

- A computer with suitable software can be used to control the microfluidic flow, the lasers and the microscope camera to record images.

Physics of the optical stretcher

Physical origin of the forces in the optical stretcher

Objects trapped in the optical stretcher usually have diameters on the scale of 10 micrometer, which is very large compared to the laser wavelengths used (often 1064 nm). It is thus sufficient to consider the interaction with the laser light in terms of ray optics.

When a ray enters the object, it is refracted due to the different refractive index according to Snell's law. Because photons carry momentum, a change in the direction of propagation of a light ray implies a momentum change, i.e. a force. According to Newton's third law, a corresponding force pointing in the opposite direction acts on the surface of the object. These surface forces due to photon momentum change are the origin for the ability of the optical stretcher to trap and stretch objects.[6]

The trapping force

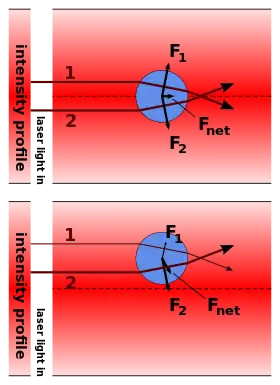

All surface forces can be added up to a resulting force pulling on the center of mass of the object, which is used to trap objects. Usually, one uses Gaussian laser beams to trap particles. The most important thing to note is that Gaussian beams have a light intensity gradient, i.e. the light intensity is high in the center of the beam (on the optical axis) and decreases off the axis.

It can be illustrative to decompose the trapping force into two components called the scattering force and the gradient force:

- The Gaussian beams used in optical stretchers are - in contrast to optical tweezers - weakly divergent. The momentum carried by the photons thus basically points in the direction of light propagation. After leaving the object, the magnitude of momentum is the same but most photons have changed in direction of propagation, such that on the whole they carry less momentum in the forward direction. This missing momentum is transferred to the object. This part is called the scattering force, because it arises from scattering the light in all directions. Because the scattering force always pushes objects in the direction of beam propagation, one needs two counterpropagating beams whose scattering forces cancel mutually in order to stably trap cells.

- The component of the force perpendicular to the laser direction is called the gradient force. If a spheroid-like object is aligned on the optical axis, these forces will cancel due to the rotational symmetry of the Gaussian beam and there is no gradient force. However, if the object is moved off the axis, there will be more rays interacting with it on the side near to the beam axis and less on the outer side.

The rays on the inner side are mostly refracted away from the beam axis (see figure on the right), leading to a corresponding force towards the beam axis on the object. The gradient force thus pulls object onto the beam axis.

This requires the refractive index of that object to be higher than the index of the surrounding medium - else the refraction would lead to opposite results, pushing particles out of the beam. However, the refractive index of biological matter is always higher than that of water or cell medium due to the additional protein content.

In the optical stretcher, two counterpropagating laser beams are used in order to cancel their corresponding scattering forces. Because their gradient forces point in the same direction, pulling particles towards their common beam axis, they add up, and one arrives at a stable trap position.

An alternative approach to understand the trapping mechanism is to consider the interaction of the particle with the electric fields of the laser beam. This leads to the known fact that electric dipoles (or dielectric, polarizable media like cells) are pulled to the region of highest field intensities, i.e. to the center of the beam. See electric dipole approximation for details.

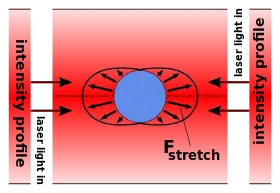

The stretching force

Once the particle is stably trapped, there is no net force on the center of mass of the particle. However, the forces appearing at the surface of the particle do not cancel, and contrary to what one might naively expect, the light does not squeeze the cell but stretch it:

The magnitude of the photon momentum is given by

where h is Planck's constant, n the refractive index of the medium and λ the wavelength of the light. The photon momentum increases when the photon enters a medium of higher refractive index. Conservation of momentum then leads to a surface force acting on the particle, pointing in the opposite direction, i.e. outwards. When a photon leaves the trapped object, its momentum decreases and again conservation of momentum requires that an outward-pointing force be exerted. Thus, as all surface forces point outwards, they do not cancel but add up.

The highest stretching forces can be found on the beam axis, where the light intensity is highest and the rays incide at right angle. Near the poles of the cell, where virtually no rays impinge, the surface forces vanish.

Different mathematical models have been developed to calculate the stretching forces, based on ray optics[7] [8] or the solution of Maxwell's equations.[9]

References

- Ashkin, A. (1970). "Acceleration and Trapping of Particles by Radiation Pressure". Phys. Rev. Lett. 24 (4): 156–159. Bibcode:1970PhRvL..24..156A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.24.156.

- Ashkin, A., Dziedzic, J.M. (1987). "Optical trapping and manipulation of viruses and bacteria". Science. 235 (4795): 1517–1520. doi:10.1126/science.3547653. PMID 3547653.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Guck, J.; et al. (2001). "The Optical Stretcher: A Novel Laser Tool to Micromanipulate Cells". Biophys. J. 81 (2): 767–784. Bibcode:2001BpJ....81..767G. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75740-2. PMC 1301552. PMID 11463624.

- Ekpenyong, A. E.; et al. (2012). "Viscoelastic Properties of Differentiating Blood Cells Are Fate- and Function-Dependent". PLoS ONE. 7 (9): e45237. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745237E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045237. PMC 3459925. PMID 23028868.

- Guck, J.; et al. (2005). "Optical Deformability as an Inherent Cell Marker for Testing Malignant Transformation and Metastatic Competence". Biophys. J. 88 (5): 3689–3698. Bibcode:2005BpJ....88.3689G. doi:10.1529/biophysj.104.045476. PMC 1305515. PMID 15722433.

- Neuman, K. C. & Block, S. M. (2004). "Optical trapping". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 75 (9): 2787–2809. Bibcode:2004RScI...75.2787N. doi:10.1063/1.1785844. PMC 1523313. PMID 16878180.

- Ekpenyong, A. E.; et al. (2009). "Determination of cell elasticity through hybrid ray optics and continuum mechanics modeling of cell deformation in the optical stretcher". Applied Optics. 48 (32): 6344–6354. Bibcode:2009ApOpt..48.6344E. doi:10.1364/AO.48.006344. PMC 3060047. PMID 19904335.

- Guck, J.; et al. (2000). "Optical Deformability of Soft Biological Dielectrics". Phys. Rev. Lett. 84 (23): 5451–5454. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84.5451G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5451. PMID 10990966.

- Guck, J.; et al. (2009). "Interaction of a Gaussian beam with a near-spherical particle: an analytic-numerical approach for assessing scattering and stresses". JOSA A. 26 (8): 1814–1826. Bibcode:2009JOSAA..26.1814B. doi:10.1364/JOSAA.26.001814.