Oral torus

An oral torus is a lesion made of compact bone and occurs along the palate or the mandible inside the mouth. The palatal torus or torus palatinus occurs along the palate, close to the midline, whereas the mandibular torus or torus mandibularis occur along the lingual side of the mandible. Oral torus, similarly known as torus palatinus, is a painless, harmless bony growth on the roof of the moth (i.e. the hard palate). The mass appears in the middle of the hard palate and can vary in size and shape, which varies with each patient.

Occurrences of oral torus cases are more frequently found in women than they are found in men. Oral torus is associated with adulthood and rarely appear on people before the age of 15. Oral torus affects about 20 to 30 percent of the population, most of whom are women of Asian descent.[2]

Treatment is not necessary unless they become an obstruction to chewing or prosthetic appliances.

Abstract

Oral torus is a bony growth in the upper or lower jaws. Tori (plural for oral torus) are not particularly common – about 5 – 10% of the population will have noticeable tori. Tori are slightly more common in males. It is believed that tori are caused by several factors but there is not one thing that always causes tori. They may be associated with bruxism or tooth clenching and grinding however no. The size of the tori may fluctuate throughout life but they do tend to get bigger over time. [3]

Tori are usually a clinical finding with no treatment necessary. It is possible for ulcers to form on the area of the tori due to trauma and rubbing against other things like food. Hard foods, such as crusty bread, or hot foods, such as pizza, may cause problems. While there have been research and clinical trails to further the understanding of oral torus, there are no current clinical trials. Additionally, there is minimal information on the disease itself.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The bony growths of oral torus are benign and typically do not have any symptoms. Additionally, they can sometimes cause the patient discomfort if the growth continues to grow. While oral torus growths are slow growing, they can sometimes grow so large that they start to interfere with speech and the ability of the patient to eat.However, it is important to note that oral torus is a completely normal anatomical feature.[5] Oral torus does not usually cause any pain or physical symptoms, however, it can have the following characteristics:

- The mass is located in the middle of the roof of the mouth.

- It can vary in size, from smaller than 2 millimeters to larger than 6 millimeters.

- The mass can take on a variety of shapes — flat, nodular, spindle-shaped — or appear to be one connected cluster of growths.

- Because it is slow growing, the mass typically begins in puberty but may not become noticeable until middle age.[6]

Causes

Oral torus are attributable to genetics and stress in relation to the jawbone—this can happen as a result of clenching or grinding of the teeth.[8]

Researches have not been able to pin-point what causes torus palatinus, but they strongly suspect it may have a strong genetic component. Other possible causes that researchers hypothesize are:

- Diet:[9]

- Researchers studying torus palatinus make remarks that it is most prevalent in countries where the population consume a large amount of saltwater fish. Some of these countries include Japan, Croatia, Norway, etc. the saltwater fish have high amounts of polyunsaturated fats and vitamin D-- both of which are important nutrients for bone growth.

- Teeth clenching/grinding:[10]

- Some researchers argue that there is a connection between the pressure placed on bony structures in the mouth when someone grinds their teeth. However, other researchers disagree.

- Having increases bone density:[11]

- While acknowledging that more study is needed, researchers have also found that white postmenopausal women with a moderate-to-large torus palatinus were more likely than others to also have normal-to-higher bone density than their counterparts.

Most tori grow to a certain point, then stop growing. Most of the tori growths after the human jaw has developed in the late teenage years. Oral tori are benign by nature, and they do not shrink over time. Tori growths with continue to grow to a certain point, and then will cease to continue growth.[12] It is believed that the tori are caused by several factors. They are more common in early adulthood and are associated with bruxism. The size of the tori may fluctuate throughout life, and in some cases the tori can be large enough to touch each other in the midline of mouth.[13]

Mechanism/Pathophysiology

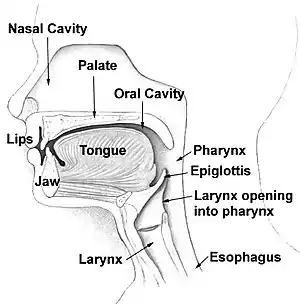

Hyperostosis is any abnormal bony growths present on the longitudinal ridge of the hard palate or lingual surface of the mandible. The torus palatinus is the maxillary form of the condition and is expressed as flat, nodular, spindle-shaped, and lobular. The torus mandibularis occurs on the mandible (commonly in the canine or premolar region), either unilaterally or bilaterally, and its shape is more amorphous and not as easily classified as the torus palatinus. Buccal and palatal exostoses are similar to tori in that they are hyperplastic bony nodules of mature trabecular and cortical bone, but they are located in different areas of the mouth and are less frequently observed than tori. Buccal exostoses are found on the buccal aspect of the mandible or maxilla and commonly near the premolars and molars. Palatal exostoses are found on the maxilla near the palatal tuberosity. Toris is a prominent midline ridge of the hard palate in the mouth and is noted in 5% of the population as a normal variant (54). The disorder can be caused by mutations in LRP5 on chromosome 11q13.2. Gain of function mutations in the amino terminal region of the LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) are responsible (56). The etiology of the exostoses and tori is not known, but the higher prevalence of the conditions in some populations suggests that there may be a genetic predisposition and environmental, functional, and age-related factors have also been suggested.[14]

Diagnosis

If the torus palatinus is big enough, the patient will be able to feel it on their own. However, if it is small, they will have little to no symptoms. Typically, it is most common for a dentist to find it during a routine oral exam.

Due to the fact that it is an abnormal growth, many patients wonder if the mass is cancerous. Any abnormal growth on the body should be further investigated, but oral cancer is rare. Occurring in just 0.11 percent of men, and 0.07 percent in women, it is unlikely that the mass would be cancerous. When oral cancer does occur, it is usually seen on the soft tissues of the mouth such as the cheeks and tongue—not the rood of the mouth.[15]

The prevalence of tori ranges from 5-40%. It is less common than bony growths occurring on the palate, known as torus palatinus. Mandibular tori are more common in Asian and Inuit populations, and slightly more common in males. In the United States, the prevalence is 7-10% of the population.

Prevention and treatment

Patients who present with oral torus should seen professional dental treatment. A dental professional would not generally recommend for the patient unless the torus growth hinders the placement of a prothesis or has caused problems with a person's oral health. As long as the growth is asymptomatic, no treatment is needed.[17] If this applies to the patient, then surgery is the most common treatment for Oral Torus. Surgery may be recommended to the patient if the bony growth:

- Makes it difficult to properly fit dentures in their mouth.

- Is so larger that it interferes with necessary daily activities such as: eating, drinking, speaking, or maintaining exceptional daily hygiene.

- It becomes so protruding that it can become scratched when the patient chews on hard foods, like chips. Because there are no blood vessels in the torus palatinus, it can be slow to heal with it has been scratched and cut.

Surgery can be performed under a local anesthetic. The patient's surgeon would typically be a maxillofacial surgeon (someone who specializes in neck, face, and jaw surgery). They would make an incision down the middle of the hard palate and remove the excess hone before closing the open sutures. The risk of complications with this surgery is relatively low, but problems can still occur. These problems include:

- nicking the nasal cavity

- infection, which can occur when you expose tissue

- swelling

- excessive bleeding

- reaction to the anesthesia (rare)

Recovery for this surgery usually takes anywhere from 3 to 4 weeks. To help minimize the discomfort and speed up the healing process, surgeons may suggest:

- taking prescribed pain medication.

- eating. soft diet to help avoid opening the sutures.

- rinsing their mouth with salt water or an oral antiseptic to cut down the risk of infection.[18]

A dental professional would not typically not recommend any type of treatment for torus moth unless the growth affected the placement of a prothesis, or caused problems with a person's oral health. As long as the growths are asymptomatic, no treatment is needed.

Similarly to other oral health conditions, it is recommended to visit a dentist twice a year to get a complete oral health examination. The dental hygienist will likely take X-rays for a comprehensive oral evaluation. Sometimes the oral torus might interfere with placing of the x-ray sensor, but correct placement is usually possible without irritating the mass.[19]

Prognosis

There is no known information on this.

Epidemiology

Oral torus is most common in Asian and Inuit populations, and slightly more common in males. In the United States, the prevalence is 7-10% of the population. They are more common in early adulthood.[20]

Research directions

In Southern Thailand, a clinical study of oral tori measured the prevalence and the relation of oral tori to parafunctional activity (i.e. the clenching and grinding of teeth. The objective of the study was to investigate the relationship of oral tori and occlusal stress—as indicated by parafunctional activity, and to report the prevalence of torus palatinus (TP) and torus mandibularis (TM) among patients attending a dental school hospital in southern Thailand. Six-hundred-nine individuals (183 males and 426 females), were interviewed and examined for the presence of clenching and grinding habit. The presence of TP and TM was also examined in each individual and in the case of TM size was recorded. Tabulated analysis was carried out to find the crude relationships of the parafunction, age and sex to the presence of tP or TM. The relationships were then analyzed by logistic regression. Of these individuals, 376 (61.7%) had TP, whereas 182 (29.9%) has TM. The male to female prevalence rations of TP and TM were 1:1.4 and 1:0.94, respectively, TP was, thus, more frequent in females. A strong association between clenching and grinding and the presence of TM was found. The presence of TM might be useful as a cue to look for signs of parafunction.[21]

Another study titled, "Genetic influence on the prevalence of torus palatinus", by Martin Gorsky aims to elaborate on the genome that codes for oral torus. In the study, Gorsky states that torus palatinus (TP) represents a benign anatomic variation. It has been suggested that genetic factors play a leading role in the occurrence of oral torus. The purpose of the study was to determine the inheritance of TP. Data was collected from members of 37 randomly selected Israel Jewish families and was later analyzed using segregation analysis. The vertical transmission of TP was found in 19 of those families—this suggests that autosomal dominant transmission was supported by the results of the segregation analysis test. A significantly higher number of affected offspring (60.3%) was observed compared to the expected figure (50%) for an autosomal dominant traits with full penetrance. This is explained by the high gene frequency of TP and the relatively high proportion of homozygous parents.[22]

References

- "Head & Neck Overview | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- "What are Tori, And Why Do I Have Them? | Julie M. Gillis, DDS". www.juliegillisdds.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "What are Tori, And Why Do I Have Them? | Julie M. Gillis, DDS". www.juliegillisdds.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "Torus Mouth: What's That Oral Growth?". www.colgate.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Torus Mandibularis". Denturaid. August 16, 2019. Archived from the original on July 19, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- "Torus Mouth: What's That Oral Growth?". www.colgate.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Dental, Best (May 16, 2020). "Tori Removal - Everything You Need To Know | Best Dental". Best Dental | Dentist in Houston, TX. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "Torus mandibularis", Wikipedia, December 8, 2020, archived from the original on December 16, 2020, retrieved December 16, 2020

- "Torus Palatinus - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Neoplastic and Non-Neoplastic Growths", Color Atlas of Farm Animal Dermatology, Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 176–180, January 12, 2018, doi:10.1002/9781119250609.ch2.10, ISBN 978-1-119-25060-9, archived from the original on December 16, 2020, retrieved December 15, 2020

- "Torus Mouth: What's That Oral Growth?". www.colgate.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- "Torus Palatinus: Symptoms, Diagnosis, Causes, and More". Healthline. December 6, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Torus Mouth: What's That Oral Growth?". www.colgate.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- "Torus mandibularis", Wikipedia, December 8, 2020, archived from the original on December 16, 2020, retrieved December 16, 2020

- Kerdpon, D.; Sirirungrojying, S. (1999–1902). "A clinical study of oral tori in southern Thailand: prevalence and the relation to parafunctional activity". European Journal of Oral Sciences. 107 (1): 9–13. doi:10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos107103.x. ISSN 0909-8836. PMID 10102745. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 14, 2020. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Gorsky, M.; Bukai, A.; Shohat, M. (January 13, 1998). "Genetic influence on the prevalence of torus palatinus". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 75 (2): 138–140. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980113)75:2<138::AID-AJMG3>3.0.CO;2-P. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 9450873. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- Ibsen, Olga A.C. & Joan Anderson Phelan, 2004. Oral Pathology for the Dental Hygienist. 4th edition. Philadelphia, Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-9946-4.