Osmundus

Osmund was a missionary bishop in Sweden in the mid-11th century. Also: Asmund; Old Swedish: Asmuðær; Latin: Osmundus, Aesmundus.

Born at an unknown date c. 1000, probably in England; educated at the schools of Bremen (shortly?) after 1014 (when his sponsor first became a 'bishop of the Norwegians'); served as court-bishop to King Emund the Old of Sweden (who reigned as sole king c. 1050 – c. 1060); was expelled from Sweden and travelled to England via Bremen probably in 1057; died as a monk of Ely in the abbacy of Thurstan (1066 - c.1072).[1]

Osmund, missionary bishop in Sweden and monk of Ely, is not to be confused with Saint Osmund, Bishop of Salisbury (d. 1099) Osmund (Bishop of Salisbury). He is also to be distinguished from Amund (d. 1082), the successor of Saint David as Bishop of Västerås[2] and from the Bishop Osmund who, as a monk of Fécamp, signed a privilege in 1017.[3] It is not entirely out of the question that the rune-carver Asmund Karesun, Asmund Karesson who produced Christian memorials in central Sweden in the 1020s and '30s, might have been the future Bishop Osmund, but this hypothesis has not won much favour in recent years.

Career

Swedish bishopric and expulsion

Bishop Osmund is best known from the hostile report on an incident in his career which Adam of Bremen derived from a memorandum on recent Swedish affairs written by Archbishop Adalbert of Hamburg-Bremen on the basis of information received from Adalward, formerly Dean of Bremen and later, Bishop of Skara.[4]

In essence, what this report tells us is that Osmund was a protégé of a bishop of the Norwegians called Sigafridus, who had sponsored his education at Bremen. By the time, in the mid-1050s, when the former Dean Adalward, along with a retinue from Bremen, travelled to Sweden with a view to his acceptance as Bishop of Skara, Osmund was serving as King Emund's court bishop and behaving as if he were the kingdom's archbishop. There ensued a clash, apparently at a public assembly, in which Osmund successfully rejected Adalward's bid to replace him in his position of primacy over the Christians of Sweden. Adalward could only supply evidence of accreditation by the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen, whereas Osmund claimed that his own authority came from the papacy, and presumably was able to produce convincing documentation to that effect, though it emerged from examination of the evidence that he had not actually received ordination at Rome, but from 'a certain archbishop of Poland'.

The delegation from Bremen was obliged to return home, fulminating against Osmund in the defamatory terms which were in due course introduced to the public domain in the third book of Master Adam's history of his archdiocese. However, already at the time of the original public controversy, at least one person present expressed strong disapproval of Osmund, maintaining that he was a promulgator of 'unsound teaching of our faith' and Stenkil, King Emund's son-in-law and eventual successor, thought well enough of Adalward to offer him some assistance with his return journey. Furthermore, public opinion in Sweden was to prove very volatile: the death of King Emund's son and heir by poisoning during a military expedition, combined with a disastrous harvest and famine (probably in 1056-7),[5] proved sufficient to turn the mood of the nation against Osmund, so that he was in his turn expelled from Sweden and Adalward recalled.

Bishop Osmund's first move, after expulsion, seems to have been to make peace with Archbishop Adalbert in Bremen. The archbishop adopted towards him his customary approach towards bishops 'consecrated elsewhere', keeping him in his company for a while in exchange for a promise of obedience, and then giving him a cordial send-off.[6] Evidently, Osmund next took ship to England, and what happened afterwards is recorded in a twelfth century chronicle, the Liber Eliensis.[7]

Retirement to Ely

He received a welcome from King Edward the Confessor and spent a considerable period at court before deciding to enter the Abbey of Ely as a monk. There, he was received by Abbot Wulfric into the community on favourable terms which required him to exercise no office other than that of a bishop. He remained in the monastery until his death 'in the times of Abbot Thurstan', that is, between 1066 and c. 1072.[8] This abbacy was famously not a peaceful era for Ely. Soon after the Norman Conquest, the resistance-leader Hereward based his militia for a period in the monastery, which endured a protracted siege before the abbot, faced by the expected arrival of Danish reinforcements to the militia, made terms with the Conqueror.[9] How much of this time of trouble Osmund may have lived through is not recorded.

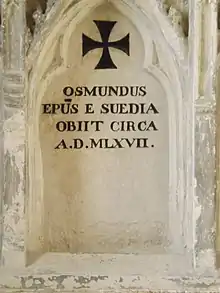

Bishop Osmund was one of seven notable individuals from the pre-Conquest era considered by the Benedictine monks of Ely to be so worthy of commemoration as benefactors that their remains, originally entombed in the abbey-church dating from 970, were carefully exhumed for preservation in the Norman-era church which was built to replace it and in 1109 became Ely Cathedral. The remains of the so-called 'Seven Confessors of' Ely have been housed, since the late 18th century, when they were last exhumed, in caskets within a monument situated in Bishop West's Chapel, at the south-east corner of the Cathedral and Osmund is commemorated simply, in Latin, as 'a bishop from out of Sweden'.[10]

Preaching and character

What exactly Osmund may have preached that could have been considered 'unsound teaching' of the Christian faith has been much discussed, but it is not a question that can be answered with any certainty today.[11] Even Bishop-elect Adalward may not have been given any clear idea about what laid behind the charge, let alone Adam of Bremen. To both, it was hear-say, not something about which they could personally testify. Osmund's alleged departure from orthodoxy is not at all likely to have been connected with the Great Schism, the significance of which was as yet little understood in the northern Germanic regions of Europe.[12] The best clues to the character of the theological milieu in which Osmund operated, and for which he may have been thought responsible, are to be found in the not always very orthodox inscriptions and mythological carvings on memorial rune-stones set up in eleventh-century Sweden by members of the Christian laity.[13]

As regards Osmund's character, background and standing as a missionary, it is not to be assumed that the characterization of him in Adam of Bremen 3, chapter 15, as an ungrateful, heretical vagabond and acephalous pseudo-archbishop, tells the whole truth about him. Happily, there is just enough evidence extant in medieval literary sources, not least in observations made by Adam of Bremen himself, to enable us to raise serious doubts about that verdict.

The fact that Osmund's education was sponsored by 'Sigafridus, a bishop of the Norwegians' locates him, in an ancient and honourable tradition of missionaries dispatched from England, or under English leadership, to parts of continental Europe beyond the bounds of Christendom.[14] For Osmund's patron has to be identified as the Sigafridus listed as the third in a succession of bishops based in Trondheim and originating from England, a bishop known by Adam of Bremen to have worked in Sweden as well as Norway. It also seems overwhelmingly probable that he was the same man remembered in Swedish hagiography and local traditions as Saint Sigfrid 'from England'.[15]

Given his close connection, and possible family relationship, with a saint known as the 'Apostle of Sweden', and his later rise to the status of a bishop in that country, it seems a near-certainty that Osmund would have spent his early career, after education in Bremen and receiving of Holy Orders, working as a junior member of Saint Sigfrid's mission team, in readiness for the day when he might prove an eligible successor to his educational sponsor.[16] Local traditions preserved in Halland, which associate the names of 'Saint Sigfrid' and 'Saint Asmund' with holy springs, may emanate from work done by the two missionaries together in that area, which, in the early eleventh century, up until King Emund's time, was territory disputed between Denmark and Sweden.[17]

Latin hagiographical sources assert that within the Swedish kingdom, Saint Sigfrid was granted land for the church at Husaby near Skara, and at Hoff and Tiurby in the vicinity of Växjö, and that he furthermore founded bishoprics for the two parts of Götaland, western and eastern, and also at Uppsala and Strängnäs.[18] This information, combined with the evidence of rune-stones datable to the earlier decades of the eleventh century, suggests the spread of 'English' missionary activity over southern and eastern-central Sweden, as far north as Uppland.[19] It may be assumed that Osmund's work could have ranged over all these areas. The incident of his clash with Adalward happened at an assembly of the Sueones, so most probably at Uppsala.[20] However, apart from Adam of Bremen's report of that incident, the only medieval literary records of Osmund's activity as a bishop in Sweden come from the bishop-lists of Skara and Växjö and so refer to his work in the southern part of the kingdom.

The Växjö list simply names him as the successor of Sigfrid, who was, understandably, honoured of the founder of Växjö's line of bishops.[21] The Skara lists,[22] late, confused and problematic authorities though they are, preserve some local historical traditions specifically about Osmund which have the ring of truth and may help to elucidate some problems raised by Adam of Bremen's account of the early years of the diocese of Skara.

According to Adam's account,[23] this diocese was founded by Archbishop Unwan of Hamburg-Bremen in the principal city of Götaland, at the behest of King Olof Skötkonung. Thurgot was its first bishop, who, however, after an unspecified length of time, was recalled to Bremen where he took sick and eventually died. After Thurgot's death, Gottskalk, Abbot of Ramesloh nominally succeeded him, but never set foot in the Swedish kingdom. Only after Osmund's expulsion, when Adalward I took up residence in his see, did Skara acquire from Hamburg-Bremen a successor for Thurgot who actually became an effective missionary-bishop. Adam says nothing about how Skara coped with the virtual vacancy-in-see between Thurgot's recall and Adalward's enthronement, a period of more than a quarter-century. Only the late-medieval bishop-lists of Skara provide clues as to what happened there in the years immediately before the accession of Bishop Adalward I.

Evidently deriving their data from local traditions quite distinct from Adam of Bremen, they make no mention of either Thurgot or Gottskalk. Instead, the message they convey is that at first it was Sigfrid 'from England' who served as bishop in the area (though his mission-base was evidently not in Skara itself);[24] that Sigfrid's immediate successor was another Englishman, named Unno, who suffered a martyr's death by stoning;[25] that he, in turn, was succeeded by Osmund, who won acceptance to the extent that he was actually enabled (presumably by the cathedral chapter and the local population) to 'sit' as bishop in Skara, and also provided with a residence at Mildu hede, on former common-land, adjacent to that of the dean, who had been there before his arrival; that he 'swore a solemn oath' and 'governed well as long as he could'.[26]

Thus Osmund was remembered respectfully in Skara's late-medieval bishop-lists, even though they contain acknowledgement that the diocese was not in a state of 'proper obedience' until his Bremen-appointed successors put this matter right.[27] Later entries in the same bishop-lists show that Osmund was by no means the last bishop with an 'English' background to hold sway at Skara.

Considered from a modern perspective, the fact that Osmund had looked to the papacy for ordination as a bishop, rather than to Bremen, need not be considered a matter for surprise or consternation. Archbishop Adalbert's dreams of setting himself up as a northern patriarch were short-lived,[28] and with regard to the provision of effective episcopal leadership for Sweden his record was deplorable.[29] Among missionaries in the 'English' tradition,[30] Bede's historical recording ensured preservation of the memory that St Augustine had been dispatched to England because of a papal initiative:[31] for Willibord of Utrecht[32] and Boniface of Fulda[33] alike, papal approval for their missions had seemed a matter of paramount importance, and we may be pretty sure that the same would have been true of Saint Sigfrid, although we happen not to have any evidence extant to prove it. Strong links between the prelates of the English church and the papal Curia were to be maintained all through the pre-Reformation period, despite their extreme geographical inconvenience.

That Osmund, having ventured to make the journey from Sweden to Rome, was, according to Adam of Bremen's report, rebuffed on arrival at his destination, need not stand to his discredit, given the frequency with which successive popes replaced one another in second quarter of the eleventh century, all too often amidst scandal and faction-fighting.[34] As for his subsequent obtaining of 'ordination' as bishop from 'a certain archbishop of Polania', it needs to be stated that 'Polania' definitely means 'Poland' and no other country.[35] Ever since the decree of Prince Mieszko I known as Dagome iudex, the Polish Church had committed itself to a particularly close relationship with Rome,[36] and, to judge from that Church's earliest records, it seems highly unlikely that any mid-eleventh-century archbishop of Poland, whether Stephen of Gniezno or Aaron of Kraków, would have consecrated a new bishop for Sweden, or anywhere else, without specific papal authorization.[37]

The task confronting Osmund as virtual or actual primate of all Sweden was an extremely difficult one. King Emund, according to Adam of Bremen, 'cared little about our religion',[38] and it seems safe to infer from the available evidence that would have been obliged, as one of his kingly duties, to preside at the nine-yearly pagan festival held at Uppsala, at which human sacrifice was practised, along with the ritual slaughter of many animals.[39] Even in Skara or thereabouts, a very famous statue of the fertility god Fricco remained on display throughout Osmund's unofficial tenure of the bishopric, only to be destroyed at a somewhat later date.[40] Osmund, like all Christian missionaries operating in the Swedish kingdom, would have been obliged to respect the agreement made by Olof Skötkonung with the traditional polytheists of his country, 'not to force anyone of the populace to give up the worship of his gods, if he did not of his own accord wish to turn to Christ'.[41]

It may well be that, in refusing a welcome to Adalward as Bremen's appointee to the see of Skara, Osmund was in breach of an oath of 'obedience' which he had sworn when enthroned there as Thurgot's de facto successor.[42] His position at King Emund's court exposed him to the charge of being morally compromised. However, all in all, it may be doubted whether he was guilty of anything worse than pragmatic improvisation in a difficult mission-field and a breach of the letter of the law committed when he was suddenly faced with a crisis threatening the continuation of the labours of love to which he had felt called as the Swedish Kingdom's leading bishop.

According to the bishop-lists of Skara, Osmund's successor in that diocese was one Stenfinðaer, identifiable with one Stenphi, who according to Adam of Bremen, had been appointed by Archbishop Adalbert to evangelize the Scrithefinni of far-northern Scandinavia. It appears that Stenfinðaer served temporarily as custodian of the diocese, and the restorer of its 'correct obedience', in the period between Osmund's expulsion and the return and enthronement of Bremen's official appointee, Bishop Adalward I. In the bishop-list of Växjö,[43] the name of Osmund's immediate, or next but one, successor is given as Siwardus, the equivalent of OE Sigewéard. Further north in the Swedish Kingdom, the most notable successors of Sigfrid, and therefore also of Osmund, in the next generation, were Saint David of Västerås[44] and Saint Eskil,[45] both originally from England.

Bibliography

Abrams, Lesley (1995), 'The Anglo-Saxons and the Christianization of Scandinavia', Anglo-Saxon England 24, pp. 213-49.

Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesie Pontificum: Latin text in Schmeidler (1917); Latin text and German translation in Trillmich 1961; English translation in Tschan 2002.

Arne, T.J. (1947), 'Biskop Osmund', Fornvännen 42, pp. 54-6.

Beckman, Bjarne (1970), 'Biskop Osmund ännu en gång', Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift 70, pp. 88-95.

Bishop-lists of Skara = Chronicon Vetus Episcoporum Scarensium and Chronicum Rhythmicum Episcoporum Scarensium auctore Brynolpho . . . Episcopo Scarensi in Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. III, part ii, pp. 112-120; for English translations of the earliest entries in these lists by Bishop Lars-Göran Lonnermark, see Fairweather 2014, pp. 210-11; 283; 286; 301.

Bishop-list of Växjö: Chronicon Vetus Episcoporum Wexionensium in Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. III, part ii, pp. 130-2.

Blake, E.O. (1962), ed. Liber Eliensis (Royal Historical Society, London: Camden 3rd Series, volume 92).

Liber Eliensis: Latin text in Blake 1962; English translation in Fairweather 2005.

Carver, Martin (2003), The Cross goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300-1300 (York & Woodbridge).

Fairweather, Janet (2005): Liber Eliensis: a History of the Isle of Ely from the seventh century to the twelfth translated with introduction, notes, appendices & indices, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge

Fairweather, Janet (2014), Bishop Osmund, A Missionary to Sweden in the Late Viking Age (Skara Stiftshistoriska Sällskaps Skriftserie, volume 71, Skara).

Garipzanov, Ildar H. (2012), 'Wandering Clerics and Mixed Rituals in the Early Christian North, c. 1000 – c. 1150', Journal of Ecclesiastical History 63, pp. 1-17.

Gustafsson, Bengt (1959), 'Osmundus episcopus e Suedia', Kyrkohistorisk Årsskrift 59, pp. 138-75.

Hallencreutz, Carl F. (1984), Adam Bremensis and Sueonia (Uppsala).

Hagiography of St Sigfrid = Historia Sancti Sigfridi Episcopi et Confessoris Latine et Suethice and Vita Sancti Sigfridi Episcopi et Confessoris in Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol II, part 1, pp. 344-370.

Janse, Otto (1958), 'Har Emund den Gamle sökt införa den grekisk-katolska läran i Sverige?' Fornvännen 53, pp. 118-24.

Janson. Henrik (1998), Templum Nobilissimum: Adam av Bremen, Uppsalatemplet och konfliktlinjerna i Europa kring år 1075 (Avhandlingar från Historiska institutionen i Göteborg 21: Göteborg)

Keynes, Simon (2003), 'The discovery of the bones of the Saxon “Confessors” ', in Meadows, Peter & Ramsay, Nigel, eds., A History of Ely Cathedral (Woodbridge), pp. 400-404.

Lager, Linn (2003), 'Runestones and the conversion of Sweden' in Carver 2003, pp. 497-507.

Niblaeus, Erik G. (2010), German influence on religious practice in Scandinavia c. 1050-1150. (Doctoral Dissertation, King's College, London)https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/2932017/539896.pdf

Schmeidler, Bernhard (1917) ed. Adam Bremensis, Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesie Pontificum (Monumenta Germaniae Historica:Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi, vol. 2, 3rd edition).

Schmidt, Toni (1934), Sveriges kristnande från verklighet till dikt (Stockholm)

Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi (Uppsala 1818-1876), vol. I, ed. E.M. Fant (1818) vol. II ed. E.J. Geijer & J.H. Schröder (1828) vol. III. ed. E. Annerstadt (1871-6)

Talbot, C.H. (1954), The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany (London).

Thompson, Claiborne W. (1970), 'A Swedish Runographer and a Headless Bishop', Mediaeval Scandinavia, pp. 50-62.

Thompson, Claiborne W. (1975), Studies in Upplandic Runography (Austin and London).

Trillmich W. (1961) ed. Quellen des 9. und 11. Jahrhunderts zur Geschichte der Hamburgischen Kirche und des Reiches (Darmstadt).

Tschan F. (2002), trans. History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, with introduction and bibliography by Timothy Reuter.

References

- Fairweather 2014, pp. 13-28.

- Fairweather (2014) p. 22.

- Fairweather (2014) p. 23.

- Adam of Bremen book 3, chapters 15-16

- Trillmich 1961, p. 347, note 1056.

- Adam of Bremen 3, chapter 77

- Liber Eliensis 2, chapter 99.

- Liber Eliensis 2, chapters 100-112.

- Fairweather 2014, pp. 323-6.

- Keynes 2003

- See Schmid 1934, pp. 61-6, Arne 1947, Janse 1958, Gustafsson 1959, Beckman 1970, Hallencreutz 1984, Janson 1998, Niblaeus 2010, pp 112-3 with note 298, Garipzanov 2012, pp. 2-3, Fairweather 2014, pp. 26-27; 158-172.

- Adam of Bremen 3, chapter 72; Fairweather 2014, p. 161.

- Fairweather 2014, pp. 165-71.

- See C.H. Talbot 1954 pp. vii-xvii.

- See Fairweather 2014, pp. 176-213.

- Fairweather 2014, pp.218-236.

- See Fairweather 2014, pp. 85-6.

- Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol II, part 1, pp. 344-370

- see Carver 2003.

- Fairweather 2014, p. 297.

- Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. III, part 2: pp. 130-2.

- Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. III, part 2, pp. 112-115.

- Adam of Bremen, book 2, chapters 58 & 64; book 2, chapters 15-16; book 4, chapter 23.

- See Fairweather 2014, p. 210.

- Fairweather 2014, pp. 210-13.

- Fairweather 2014, pp. 283-6.

- See entry on Osmund's successor, Stenfinðaer; Fairweather 2014, pp. 286-7.

- Adam of Bremen, book 3, chapters 72-78

- Adam of Bremen, book 4, chapters 23 (with scholium 136); chapters 29-30.

- English translations of select texts in Talbot 1954.

- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, book 1, chapters 23-33 & book 2, chapters 1-3.

- See, e.g. Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, book 5, chapter 11.

- Boniface, Epistulae, for correspondence with Popes Gregory II and III, Zacharias and Stephen; also Willibald, Vita Bonifatii 5.

- Fairweather (2014) pp. 246-7

- Fairweather (2014) pp. 249-50.

- Fairweather (2014) p. 253.

- Fairweather (2014), pp. 278-9.

- Adam of Bremen, book 3, chapter 15.

- Adam of Bremen, book 4, chapters 26-30.

- Adam of Bremen, book 4, chapter 9.

- Adam of Bremen, book 2, chapter 58.

- Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. 3, part 2, paragraphs 3 & 4; Fairweather (2014) pp. 283-7.

- Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, Vol. III.ii, pp. 130-2.

- See: Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum Medii Aevi, vol. 2, part 1, 405-410 for Historia Sancti Davidis Abbatis et Confessoris.

- See: Scriptores Rerum Suecicarum, vol 2, part 1, pp. 389-95 for Legenda Sancti Eskilii.