Ozark hellbender

The Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi) is a subspecies of the hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis), strictly native to the mountain streams of the Ozark Plateau in southern Missouri and northern Arkansas.[1] Their nicknames include lasagna lizard and snot otter.[2] These large salamanders grow to average from 29-57 centimeters in length over a lifespan of 30 years.[3] Ozark hellbenders are nocturnal predators that reside under large flat rocks and primarily consume crayfish and small fish. As of 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has listed the subspecies as endangered under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.[4] The species population decline is caused by habitat destruction and modification, overutilization, disease and predation, and low reproductive rates.[5] Conservation programs have been put in place to help protect the species.[6][5]

| Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Cryptobranchidae |

| Genus: | Cryptobranchus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. a. bishopi |

| Trinomial name | |

| Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi Grobman, 1943 | |

| |

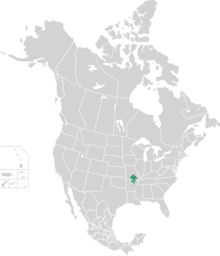

| Distribution map of the Ozark hellbender | |

Taxonomy

Two distinct members of the family Cryptobranchidae, also known as "giant salamanders," are found in the United States, the eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus a. alleganiensis), and the Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus a. bishopi).[7]

Description

Hellbenders are known for their primitive body design and their large size. They have small eyes, a keeled tail, and a flat body to assist the Ozark hellbender in movement in rivers and streams.[8] They have folds along their sides that assist them in respiration, as oxygen is able to diffuse across the skin.[3] It is a strictly aquatic species, even though it technically lacks gills.[9] On average, they are about 29-57 centimeters in length.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Ozark hellbenders are endemic to the White River drainage in northern Arkansas and southern Missouri. Historically they have been found in portions of Spring, White, Black, Eleven Point, and Current Rivers and their tributaries. Hellbenders are now considered extirpated in the mainstem White, Black, and Spring Rivers and Jacks Fork, and with their range being considerably reduced in the remaining rivers and tributaries.[10]

The Ozark hellbender is declining throughout its range with no population appearing to be stable throughout its range.[11] It is unknown whether a viable population exists in the mainstem of the White River, where few individuals have been found. Much of the potential habitat along this river has been destroyed by a series of dams constructed on the upper portion of the river in the 1940s and 1950s.[12] The North Fork White River has historically contained a high population of Ozark hellbenders and was considered the strong point for the species with a mark and recapture study in 1973 marking 1,150 individuals within a 1.7-mile reach of the river.[13] In recent years, this population is now beginning to experience a decline similar to those in populations in other rivers.[12] Though the overall population of the Ozark hellbender is known to be in decline, there is no data available on current population sizes, likely due to their small numbers and reclusive life history.[14]

There is currently no critical habitat designated for the Ozark hellbender.[4]

Ozark hellbenders are frequently found underneath large flat rocks in rocky, fast flowing streams in the Ozark Plateau at depths from less than 1 meter to 3 meters.[8] They are primarily nocturnal, remaining undercover until nightfall. Hellbenders are habitat specialists that are dependent on consistent levels of dissolved oxygen, temperature, and water flow.[15] Warmer stagnant waters with a low dissolved oxygen content do not meet the Ozark hellbenders respiratory needs.[15] It has been observed that Ozark hellbenders in warm stagnant waters sway or rock in order to increase oxygen exposure.[15]

Ecology and behavior

Ozark hellbenders are nocturnal predators, remaining beneath rock cover during the day and emerging to forage at night, primarily on crayfish.[16] They become diurnal during the breeding season, searching for mates.[3] They are highly sedentary, moving very little throughout their entire lifespan.[16] Ozark hellbenders are territorial and will defend their cover from other hellbenders.

They have been recorded living 25 to 30 years in the wild and grow slowly over time.[17] Wild Ozark hellbender populations are dominated by these older and larger individuals. Female Ozark hellbenders have been found to mature at 6 to 8 years old, while males tend to mature at around 5 years of age.[1][17][18] Some of the issues that Ozark hellbenders have in reproduction come from their late sexual maturity.[5]

Typically, Ozark hellbenders breed in mid-October, although certain populations that live in the Spring River area tend to procreate in the winter. Paternal care is present in this subspecies, even though it is rare to see this in tetrapods.[19] The males are responsible for preparing the nests and ultimately guarding the eggs. They build nests under submerged logs, flat rocks, or within bedrocks. Hellbenders mate via external fertilization.[1] Usually, around 138 to 450 eggs are present per nest,[3] and they hatch after approximately 80 days.[20] Once the eggs hatch, the larvae and juveniles hide under small and large rocks in gravel beds.[1][21] Ozark hellbenders are highly sedentary creatures, meaning that neither males nor females have long distance dispersal rates.[8]

Conservation status

The Endangered Species Act of 1973

The Ozark hellbender became a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act in 2001. It was assigned a priority level of 6 for threats due to habitat loss and fragmentation because of human activity and pollution.[22] In 2005 the Fish and Wildlife Service increased its listing priority number to a 3 because of increased pressures on the species from recreation activity in their habitat including gigging and boat traffic, and increases in the contamination of their waters.[23] The USFWS put forth the proposed rule to list the Ozark hellbender as endangered under the ESA in September 2010, and the listing of the species as endangered became effective November 7, 2011.[4][24] In April 2017, a five-year review of the subspecies’ status was initiated.[25]

IUCN

The subspecies of C. a. bishopi does not currently have its own IUCN listing, but the species C. alleganiensis was listed as near threatened in April 2004.[14]

Threats

Human impact

The construction of reservoirs in the White River has destroyed Ozark hellbender habitat and separated their populations.[5] These reservoirs also increase predation and the deposition of silt upstream from the reservoir, both of which threaten hellbenders.[5] Siltation endangers the larval salamanders because it fills in the gravel stream beds where they live, reducing their ability to find food and hide from predators. Silt can also destroy their eggs.[5] Agricultural and construction runoff, waste disposal, and mining activity within the hellbender’s range pollute and degrade their habitat and threaten hellbender survival.[5][23] Mining is especially detrimental as it increases zinc and lead levels in hellbender habitat to dangerously high levels for aquatic life.[8] Human and livestock waste from the areas surrounding hellbender habitat have further decreased water quality.[23] Pollution is readily taken up by hellbenders due to the absorptive properties of their skin and decreases in water quality can make rivers and streams unlivable for this subspecies.[8][15]

Recreation in Ozark hellbender habitat also harms populations. Boat traffic, including canoes, kayaks, and motor boats may injure or kill hellbenders and further degrade their habitat.[8][23]

Additionally, direct removal from the environment has contributed to the decline of the Ozark hellbender. While Missouri and Arkansas have decreased or stopped issuing permits for scientific collection since the 1990s, illegal harvesting for the pet trade has continued.[5][8] The Ozark hellbender also experiences predation from non-native rainbow and brown trout stocked in river for sport fishing.[5][8]

Other threats

Like most amphibians globally, the Ozark hellbender is at risk of chytridiomycosis, a very infectious amphibian fungal disease. It has been detected in all but two rivers C. a. bishopi is currently found in. Additionally, unusual physical abnormalities have been observed in Ozark hellbenders in recent years, such as missing limbs or eyes and epidermal lesions, with increasing frequency, although the cause of these deformities is currently unknown.[5][8]

The small size of Ozark hellbender populations combined with their isolation from each other puts them at greater risk of extinction, as does the documented loss of genetic diversity within those populations.[5][8] They also suffer from very low reproductive rates as a result of their late sexual maturity and long lifespans. Their late sexual maturity makes them more likely to die before reproducing and the time between generations is extended when reproduction does occur. Very low numbers of juvenile Ozark hellbenders in most populations confirm these problems.[8] These threats are further worsened when combined with the other threats to this subspecies.[5][8]

Conservation efforts

The decline of the Ozark hellbender was first recognized in the 1990s. Since then, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (AGFC) and Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) have begun to track the health and wellbeing of the creatures. They also study trends in their size and overall presence in their natural habitat. From this information, they are able to predict population trends. Since this species is now considered endangered, there is more effort to protect the habitat and populations of the Ozark hellbender. Both USFWS and State agencies have enacted laws and policies to aid in hellbender protection.[5]

The most popular conservation strategy for the Ozark hellbender is captive breeding and reintroduction back into their natural habitats. There is currently only one successful example of successful captive breeding, which is taking place in the Saint Louis Zoo.[6] In regards to hellbender release after captive breeding, planning should include data on genetic information and the presence of chytrid fungus and other pathogens. Since there is little gene flow or genetic variation in the subspecies, it is hard to continue to build their numbers due to negative consequences from inbreeding. Some scientists suggest research into their genetic delineations for answers. Not much is known about their genetic history. Many scientists also suggest that translocation should not be a part of Ozark hellbender conservation plans, since they are habitat specialists and haven’t had translocation success in the past.[26] Other current conservation plans include population monitoring, protecting populations and habitat, and disease assessment and treatment [5]

Due to the impact of disease on the Ozark hellbender populations, there is more effort to study the physical deformities of the hellbenders affected by disease, as well as understanding how diseases cause the deformities. Research is also exploring the effects of the amphibian chytrid fungus. Heat treatment has seen some success as a method of treating chytrid cases.[5]

Other than captive release programs, the recommended way to meet the recovery needs of Ozark hellbenders is to protect and clean their habitat. It is necessary to decrease sedimentation and to protect areas where Ozark hellbenders reproduce.[5]

References

- Nickerson, M.A., and C.E. Mays. 1973. The hellbenders: North American giant salamanders. Milwaukee Public Museum Publications in Biology and Geology 1:1−106.

- "VIDEO: Snot Otters Get A Second Chance In Ohio". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- Dundee, H.A., and D.S. Dundee. 1965. Observations on the systematics and ecology of Cryptobranchus from the Ozark plateaus of Missouri and Arkansas. Copeia 1965:369−370.

- Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Endangered Status for the Ozark Hellbender Salamander, 76 Fed. Reg. 61956 (Oct. 6, 2011) (to be codified at 50 C.F.R. pt 17).

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Recovery Outline for the Ozark Hellbender. Columbia, Missouri. 13 pp.

- A., Rachel, et al. “Quantitative Behavioral Analysis of First Successful Captive Breeding of Endangered Ozark Hellbenders.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 14 Nov. 2018, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2018.00205/full.

- Hayes, Thomas. "Cryptobranchid update: eastern hellbender/Ozark hellbender 'North America's Largest Salamander'." Endangered Species Update, vol. 24, no. 2, 2007, p. 42+. Accessed 1 Apr. 2020.

- "Regulations.gov". www.regulations.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- Guimond, Robert W., and Victor H. Hutchison. “Aquatic Respiration: An Unusual Strategy in the Hellbender Cryptobranchus Alleganiensis Alleganiensis (Daudin).” Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 21 Dec. 1973.

- Johnson, T. R. (2000): The amphibians and reptiles of Missouri. Jefferson, MO: Missouri Department of Conservation.

- Wheeler, B. A., E. Prosen, A. Mathis, and R. F. Wilkinson. 2003. Population declines of a long-lived salamander: a 20+-year study of hellbenders, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. Biological Conservation 109:151-156.

- Irwin, K. 2008. Ozark hellbender long-term monitoring SWG project. Final Report. Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, Benton, Arkansas.

- Peterson, C. L., R. F. Wilkinson, Jr., M. S. Topping, and D. E. Metter. 1983. Age and growth of the Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi). Copeia 1983(1):225-231.

- "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cryptobranchus alleganiensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004-04-30. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- Williams, R. D., J. E. Gates, and C. H. Hocutt. 1981. An evaluation of known potential sampling techniques for hellbender, Cryptobranchus alleganiensis. Journal of Herpetology 15(1):23-27.

- Dierenfeld, E. S., K. J. McGraw, K. Fritsche, J. T. Briggler, and J. Ettling. 2009. Nutrient composition of whole crayfish (Orconectes and Procambarus species) consumed by hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis). Herpetological Review 40(3):324-330.

- Peterson, C.L., Ingersol, C.A., and R.F. Wilkinson. 1989. Winter breeding of Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi in Arkansas. Copeia 1989:1031-1035.

- Taber, C.A., R.F. Wilkinson, Jr., and M.S. Topping. 1975. Age and growth of hellbenders in the Niangua River, Missouri. Copeia 1975:633−639.

- Bishop, et al. “A Quantitative Field Study of Paternal Care in Ozark Hellbenders, North America's Giant Salamanders.” Journal of Ethology, Springer Japan, 1 Jan. 1970, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10164-018-0553-0.

- Bishop, S.C. 1941. Salamanders of New York. New York State Museum Bulletin 324:1−365.

- LaClaire, L. V. 1993. Status review of Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus bishopi). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service status review. Jackson, Mississippi.

- Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Plant and Animal Species That Are Candidates or Proposed for Listing as Endangered or Threatened, Annual Notice of Findings on Recycled Petitions, and Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions, 66 Fed. Reg. 54811 (Oct. 30, 2001).

- Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Review of Native Species That Are Candidates or Proposed for Listing as Endangered or Threatened; Annual Notice of Findings on Resubmitted Petitions; Annual Description of Progress on Listing Actions, 70 Fed. Reg. 24877 (May 11, 2005).

- Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Rule To List the Ozark Hellbender Salamander as Endangered, 75 Fed. Reg. 54561 (Sep. 8, 2010).

- Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Initiation of 5-Year Status Reviews of Eight Endangered Animal Species, 82 Fed. Reg. 18156 (Apr. 17, 2017).

- Arntzen, et al. “Genetic Relationships of Hellbenders in the Ozark Highlands of Missouri and Conservation Implications for the Ozark Subspecies (Cryptobranchus Alleganiensis Bishopi).” Conservation Genetics, Springer Netherlands, 1 Jan. 1999.