Pak Tu-jin

Pak Tu-jin (also transliterated as Park Dujin) (1916 – September 16, 1998) was a Korean poet.[1] A voluminous writer of nature poetry, he is chiefly notable for the way he made of his subjects symbols of the newly emerging national situation of Korea in the second half of the 20th century.

Pak Tu-jin | |

|---|---|

| Born | March 10, 1916 |

| Died | September 16, 1998 (aged 82) |

| Language | Korean |

| Nationality | South Korean |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 박두진 |

| Hanja | 朴斗鎭 |

| Revised Romanization | Bak Du(-)jin |

| McCune–Reischauer | Pak Tu-jin |

| Pen name | |

| Hangul | 혜산 |

| Hanja | 兮山 |

| Revised Romanization | Hyesan |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hyesan |

Life

Pak was born in Anseong, 40 miles from Seoul in modern-day South Korea, an area to which he often refers nostalgically in his poetry. His family was too poor to give him any formal education, but two early poems of his appeared in the publication Munjang (Literary composition) in 1939. After Korea's liberation, he created the Korean Young Writers' Association alongside Kim Tong-ni, Cho Yeonhyeon, and Seo Jeongju. At that time he shared a first collection of poetry with Park Mok-wol and Cho Chi-hun. This was the Blue Deer Anthology (Cheongnokjip, 1946), which was followed by individual collections of his own, Hae (The Sun, 1949), Odo (A Prayer at Noon, 1953) and several more, distinguished by their treatment of nature.

The poet worked in a managerial position until 1945, then in publishing and later as a professor in various universities.[2] Among the awards given his poetry were the Asian Free Literature Prize (1956), Seoul City Cultural Award (1962), Samil Culture Award (1970), Korean Academy of Art Prize (1976) and the Inchon Prize (1988).

Work

The Literature Translation Institute of Korea summarizes the contribution made to Korean literature by Pak Tu-jin (who sometimes wrote under the pen name ‘Hyesan’):

- Park Dujin is one of the most prolific and renowned poets in all of modern Korean literature...Through verses that sing of green meadows, twittering birds, frolicking deer, and setting suns, the poet is often understood by critics to be presenting his own creative commentary on social and political issues. According to one theorist, “A Fragrant Hill” (HyangHyeon), one of Park’s first published poems, uses just such imagery to prophecy Korea’s liberation from Japan. The ‘peaceful co-existence of wild animals and plants’ in “HyangHyeon”, for example, can be interpreted as standing for the ‘latent power of the nation,’ with the flame that rises from the ridge symbolizing the ‘creative passion of the people.’ [3]

- It is because of this particular significance held by the natural symbols in Park’s poetry that the lyrical quality of his poems is set apart from the romantic, pastoral lyricism of many other representative Korean poets. The role of the natural world in Park Dujin’s poetry is that of a catalyst for understanding the world of man, rather than an end in itself. To 'characterize (his) poetic stance as involving a state of exchange between or joining of the self and nature', according to literary critic Cho Yeonhyeon, 'is incorrect from the outset. Park operates from a standpoint that presupposes the impossibility of even distinguishing between the two'.[4]

- With the further publication of his collections ... Park also began to draw a Christian ideal into his poetry and, in so doing, to display a particular poetic direction. Inspired by a powerful consciousness of his people’s situation in the aftermath of the Korean War, Park went on to publish works that demonstrated both rage and criticism in reference to various policies and social realities that he himself saw to be nothing short of absurd. Even through the sixties, with the collections The Spider and the Constellation (Geomi wa Seongjwa, 1962) and A Human Jungle (Ingan millim, 1963), Park continued to seek a creative resolution to the trials of his time, representing history not as a given, but as a process shaped by all its participants.

The onomatopoeia, figurative expressions, and the poetic statements in prose form used so boldly are perhaps the most notable technical devices in Park's poems from this period. With the onset of the 1970s, when he published such collections as Chronicles of Water and Stone (Suseok yeoljeon, 1973) and Poongmuhan, the nature of his poetry evolved once again; founded now on private self-realization, these poems are often said to reveal Park's attainment of the absolute pinnacle of self-discovery at which ‘infinite time and space are traveled freely.’ As such, Park, known as an artist who elevated poetry to the level of ethics and religion, is today evaluated more as a poet of thematic consciousness than of technical sophistication.[5]

His poem “Peaches are in bloom” is a good example of the way his rapturous and incantatory verse unites cultural and personal references to make it expressively symbolic of his country.

Tell them that the peaches are in bloom and the apricots

By the warm home you left abandoned, and now on that hedge once recklessly trampled, cherries and plums ripen.

Bees and butterflies praise the day, and the cuckoo sings by moonlight.

In the five continents and six oceans, O Ch’ôl, beyond the hoofed clouds and winged skies, into which corner shall I look in order to stand face to face with you?

You are deaf to the sad note of my flute in the moonlit garden, and to my songs of dawn on the green peak.

Come, come quickly, on the day when the stars come and go, your scattered brothers return one by one. Suni and your sisters, our friends, Maksoe and Poksuri too return.

Come then, come with tears and blood, come with a blue flag, with pigeons and bouquets.

Come with the blue flag of the valley full of peach and apricot blossoms.

The south winds caress the barley fields where you and I once frolicked together, and among the milky clouds larks sing loud.

On the hill starred with shepherd’s purse, lying on the green hill, Ch’ôl, you will play on the grass flute, and I will dance a fabulous roc dance.

And rolling on the grass with Maksoe, Tori and Poksuri, let us, let us unroll our happy days, rolling on the blue-green young grass.[6]

Heritage

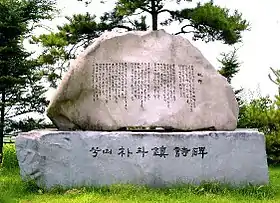

After Pak Tu-jin's death in 1998, a boulder with his poem "Nostalgia" inscribed on it was erected in his memory at the entrance of Anseong Municipal Library.[7] The Pak Tu-jin Hall on the library's third floor was opened in 2008. This is dedicated to the poet's literary work and life and also has on display examples of his calligraphy and ceramics on which he had inscribed his poems. The Pak Tu-jin Memorial Society based in Anseong hosts a national essay contest in memory of the poet as well as the annual Pak Tu-jin Literature Festival.[8]

Works in translation

- Sea of Tomorrow, forty poems by Pak Tu-jin, translated by Edward W. Poitras, Seoul 1971

- "A reading of seven poems by Pak Tu-jin", Yi Sang-sop, Korea Journal, Nov. 1981, pp.39—46

- Poems from The Lives of the Stones, Korean Literature Today 1.3, 1996

- River of Life, River of Hope (박두진 시선): Selected Poems of Pak Tu-Jin, translated by Edward W. Poitras, Norwalk Ct, 2005; two poems; three poems

- A study guide for Pak Tu-jin’s “August River”, Farmington Hills MI, 2016

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pak Tu-jin |

References

- ”Pak Dujin" LTI Korea Datasheet available at LTI Korea Library or online at: http://klti.or.kr/ke_04_03_011.do# Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ”Pak Dujin" LTI Korea Datasheet available at LTI Korea Library or online at: http://klti.or.kr/ke_04_03_011.do# Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Source-attribution|"Pak Dujin" LTI Korea Datasheet available at LTI Korea Library or online at: http://klti.or.kr/ke_04_03_011.do# Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Source-attribution|"Pak Dujin" LTI Korea Datasheet available at LTI Korea Library or online at: http://klti.or.kr/ke_04_03_011.do# Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Source-attribution|"Pak Dujin" LTI Korea Datasheet available at LTI Korea Library or online at: http://klti.or.kr/ke_04_03_011.do# Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Translation by Peter H. Lee, Poems from Korea, Hawaii University 1974, pp.175-6

- Korean heritage

- Gyeonggi Tourism Organization