Palau

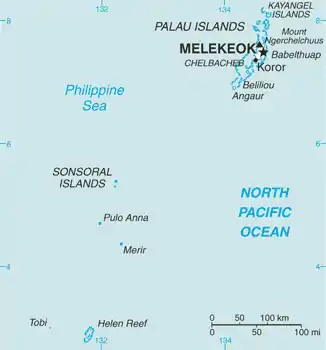

Palau /pəˈlaʊ/ (![]() listen), officially the Republic of Palau (Palauan: Beluu er a Belau)[7] and historically Belau, Palaos or Pelew, is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. The country contains approximately 340 islands, and together with parts of the Federated States of Micronesia, forms the western chain of the Caroline Islands. Its area is 466 square kilometers (180 sq mi).[8] The most populous island is Koror. The capital Ngerulmud is located on the nearby island of Babeldaob, in Melekeok State. Palau shares maritime boundaries with international waters to the north, Micronesia to the east, Indonesia to the south, and the Philippines to the west.

listen), officially the Republic of Palau (Palauan: Beluu er a Belau)[7] and historically Belau, Palaos or Pelew, is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. The country contains approximately 340 islands, and together with parts of the Federated States of Micronesia, forms the western chain of the Caroline Islands. Its area is 466 square kilometers (180 sq mi).[8] The most populous island is Koror. The capital Ngerulmud is located on the nearby island of Babeldaob, in Melekeok State. Palau shares maritime boundaries with international waters to the north, Micronesia to the east, Indonesia to the south, and the Philippines to the west.

Republic of Palau | |

|---|---|

_(small_islands_magnified).svg.png.webp) | |

_-_PLW_-_UNOCHA.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital | Ngerulmud 7°30′N 134°37′E |

| Largest city | Koror 7°20′N 134°29′E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2015[1]) |

|

| Religion (2015)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Palauan |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic under a non-partisan democracy |

| Surangel Whipps Jr. | |

| Uduch Sengebau Senior | |

• Senate President | Hokkons Baules |

• House Speaker | Sabino Anastacio |

• Chief Justice | Arthur Ngiraklsong |

• Chairman of Council of Chiefs | Ibedul Yutaka Gibbons |

| Legislature | Olbiil era Kelulau |

| Senate | |

| House of Delegates | |

| Independence from the United States | |

| 18 July 1947 | |

• Constitution | 2 April 1979 |

• Establishment of the Republic of Palau | 1 January 1981 |

| 1 October 1994 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 459 km2 (177 sq mi) (179th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 17,907[3][4] (224th) |

• 2013 census | 20,918 |

• Density | 46.7/km2 (121.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $300 million[5] |

• Per capita | $16,296[5] (81st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $322 million[5] |

• Per capita | $17,438[5] |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 50th |

| Currency | United States dollar (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (PWT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +680 |

| ISO 3166 code | PW |

| Internet TLD | .pw |

Website PalauGov.pw | |

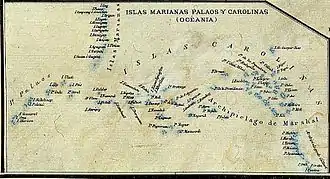

The country was originally settled approximately 3,000 years ago by migrants from Maritime Southeast Asia.[9][10] Spain was the first European nation to explore the islands in the 16th century, and they were made part of the Spanish East Indies in 1574. Following Spain's defeat in the Spanish–American War in 1898, the islands were sold to Imperial Germany in 1899 under the terms of the German–Spanish Treaty, where they were administered as part of German New Guinea. After World War I, the islands were made a part of the Japanese-ruled South Seas Mandate by the League of Nations. During World War II, skirmishes, including the major Battle of Peleliu, were fought between American and Japanese troops as part of the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign. Along with other Pacific Islands, Palau was made a part of the United States-governed Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in 1947. Having voted against joining the Federated States of Micronesia in 1979, the islands gained full sovereignty in 1994 under a Compact of Free Association with the United States.

Politically, Palau is a presidential republic in free association with the United States, which provides defense, funding, and access to social services. Legislative power is concentrated in the bicameral Palau National Congress. Palau's economy is based mainly on tourism, subsistence agriculture and fishing, with a significant portion of gross national product (GNP) derived from foreign aid. The country uses the United States dollar as its currency. The islands' culture mixes Micronesian, Melanesian, Asian, and Western elements. Ethnic Palauans, the majority of the population, are of mixed Micronesian, Melanesian, and Austronesian descent. A smaller proportion of the population is of Japanese descent. The country's two official languages are Palauan (a member of the Austronesian language family) and English, with Japanese, Sonsorolese, and Tobian recognized as regional languages.

Etymology

The name for the islands in the Palauan language, Belau, derives from the Palauan word for "village", beluu,[11] or from aibebelau ("indirect replies"), relating to a creation myth.[12] The name "Palau" entered the English language from the Spanish Los Palaos, via the German Palau. An archaic name for the islands in English was the "Pelew Islands".[13] Palau is unrelated to Pulau, which is a Malay word meaning "island" found in a number of place names in the region.

History

German New Guinea 1899–1914

German New Guinea 1899–1914 Imperial Japanese Navy occupation 1914–1919

Imperial Japanese Navy occupation 1914–1919 South Seas Mandate 1919–1944

South Seas Mandate 1919–1944.svg.png.webp) United States military occupation 1944–1947

United States military occupation 1944–1947 Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands 1947–1981

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands 1947–1981 Republic of Palau 1981–present

Republic of Palau 1981–present

Early history

Palau was originally settled between the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE, most likely from the Philippines or Indonesia.[14] Sonsorol, part of the Southwest Islands, an island chain approximately 600 kilometers (370 mi) from the main island chain of Palau, was sighted by the Spanish as early as 1522, when the Spanish mission of the Trinidad, the flagship of Ferdinand Magellan's voyage of circumnavigation, sighted two small islands around the 5th parallel north, naming them "San Juan".[15]

After the 16th century

The next recording of the existence of Palau by Europeans came a century later in 1697 when a group of Palauans were shipwrecked on the Philippine island of Samar to the northwest. They were interviewed by the Czech missionary Paul Klein on 28 December 1696. Klein was able to draw the first map of Palau based on the Palauans' representation of their home islands that they made with an arrangement of 87 pebbles on the beach . Klein reported his findings to the Jesuit Superior General in a letter sent in June 1697.[16]

Spanish era

This map and the letter caused a vast interest in the new islands. Another letter written by Fr. Andrés Serrano was sent to Europe in 1705, essentially copying the information given by Klein. The letters resulted in three unsuccessful Jesuit attempts to travel to Palau from Spanish Philippines in 1700, 1708 and 1709. The islands were first visited by the Jesuit expedition led by Francisco Padilla on 30 November 1710. The expedition ended with the stranding of the two priests, Jacques Du Beron and Joseph Cortyl, on the coast of Sonsorol, because the mother ship Santísima Trinidad was driven to Mindanao by a storm. Another ship was sent from Guam in 1711 to save them only to capsize, causing the death of three more Jesuit priests. The failure of these missions gave Palau the original Spanish name Islas Encantadas (Enchanted Islands).[17] Despite these early misfortunes, the Spanish Empire later came to dominate the islands.

Transitions era

British traders became regular visitors to Palau in the 18th century, followed by expanding Spanish influence in the 19th century. Palau, under the name Palaos, was included in the Malolos Congress in 1898, the first revolutionary congress in the Philippines, which wanted full independence from colonialists. Palau, at the time, was part of the Spanish East Indies headquartered in the Philippines. Palau had one appointed member to the Congress, becoming the only group of islands in the entire Caroline Islands granted high representation in a non-colonial Philippine Congress. The Congress also supported the right of Palau to self-determination if ever it wished to pursue such a path.[18] Later in 1899 as part of the Caroline Islands, Palau was sold by the Spanish Empire to the German Empire as part of German New Guinea in the German–Spanish Treaty (1899). During World War I, the Japanese Empire annexed the islands after seizing them from Germany in 1914. Following World War I, the League of Nations formally placed the islands under Japanese administration as part of the South Seas Mandate. In World War II, Palau was used by Japan to support its 1941 invasion of the Philippines, which succeeded in 1942. The invasion overthrew the American-installed Commonwealth government in the Philippines and installed the Japanese-backed Second Philippine Republic in 1943.[19]

United States era

During World War II, the United States captured Palau from Japan in 1944 after the costly Battle of Peleliu, when more than 2,000 Americans and 10,000 Japanese were killed. In 1945–1946, the United States re-established control on the Philippines, and managed Palau through the Philippine capital of Manila. By the later half of 1946, however, the Philippines was granted full independence with the formation of the Third Republic of the Philippines, shifting the US Far West Pacific capital to Guam. Palau passed formally to the United States under United Nations auspices in 1947 as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 21.

Independence

Four of the Trust Territory districts joined together and formed the Federated States of Micronesia in 1979, but the districts of Palau and the Marshall Islands declined to participate. Palau, the westernmost cluster of the Carolines, instead opted for independent status in 1978, which was widely supported by the Philippines, Taiwan, and Japan. It approved a new constitution and became the Republic of Palau on 1 January 1981.[20] It signed a Compact of Free Association with the United States in 1982. In the same year, Palau became one of the founding members of the Nauru Agreement. After eight referenda and an amendment to the Palauan constitution, the Compact was ratified in 1993. The Compact went into effect on 1 October 1994,[21] making Palau de jure independent, although it had been de facto independent since 25 May 1994, when the trusteeship ended. Formal diplomatic relations with the Philippines was re-established in the same year, although the two nations already had diplomatic back channels prior to 1994. Palau also became a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, but withdrew in February 2021 after a dispute regarding Henry Puna's election as the Forum's secretary-general.[22][23]

Legislation making Palau an "offshore" financial center was passed by the Senate in 1998. In 2001, Palau passed its first bank regulation and anti-money laundering laws. In 2005, Palau led the Micronesia challenge, which would conserve 30% of near-shore coastal waters and 20% of forest land of participating countries by 2020. In 2011, Palau created the world's first shark sanctuary, banning commercial shark fishing within its waters. In 2012, the Rock Islands of Palau was declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[24] In 2015, Palau became a member of the Climate Vulnerable Forum under the chairmanship of the Philippines, and at the same time, the country officially protected 80% of its water resources, becoming the first country to do so.[25] The protection of its water resources made significant increases in the country's economy in less than two years.[26] In 2017, the nation became the first to establish an eco-promise, known as the Palau Pledge, which are stamped on local and foreign passports.[27] In 2018, Palau and the Philippines began re-connecting their economic and diplomatic relations. The Philippines supported Palau to become an observer state in ASEAN, as Palau also has Southeast Asian ethnic origins.[28]

Politics and government

Palau is a democratic republic. The President of Palau is both head of state and head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government, while legislative power is vested in both the government and the Palau National Congress. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. Palau adopted a constitution in 1981.

The governments of the United States and Palau concluded a Compact of Free Association in 1986, similar to compacts that the United States had entered into with the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands.[29] The compact entered into force on 1 October 1994, concluding Palau's transition from trusteeship to independence[29] as the last portion of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands to secure its independence pursuant to Security Council Resolution 956.

The Compact of Free Association between the United States and Palau[30] sets forth the free and voluntary association of their governments. It primarily focuses on the issues of government, economic, security and defense relations.[31] Palau has no independent military, relying on the United States for its defense. Under the compact, the American military was granted access to the islands for 50 years. The U.S. Navy role is minimal, limited to a handful of Navy Seabees (construction engineers). The U.S. Coast Guard patrols in national waters.

Foreign relations

_%E8%B4%88%E7%A6%AE_(27163347055).jpg.webp)

As a sovereign nation, Palau conducts its own foreign relations.[29] Since independence, Palau has established diplomatic relations with a number of nations, including many of its Pacific neighbors, like Micronesia and the Philippines. On 29 November 1994, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 963 recommending Palau's admission to the United Nations. The United Nations General Assembly approved admission for Palau pursuant to Resolution 49/63 on 15 December 1994.[32] Palau has since joined several other international organizations. In September 2006, Palau hosted the first Taiwan-Pacific Allies Summit. Its President has made official visits to other Pacific countries, including Japan.[33]

The United States maintains a diplomatic delegation and an embassy in Palau, but most aspects of the countries' relationship have to do with Compact-funded projects, which are the responsibility of the U.S. Department of the Interior's Office of Insular Affairs.[34] For example, as part of this Compact, Palau was granted zip codes 96939 and 96940, along with regular US Mail delivery.

In international politics, Palau often votes with the United States on United Nations General Assembly resolutions.[35]

Palau has maintained close ties with Japan, which has funded infrastructure projects including the Koror–Babeldaob Bridge. In 2015, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko visited Peleliu to honor the 70th anniversary of World War II.[36]

Palau is a member of the Nauru Agreement for the Management of Fisheries.[37]

In 1981, Palau voted for the world's first nuclear-free constitution. This constitution banned the use, storage and disposal of nuclear, toxic chemical, gas and biological weapons without first being approved by a 3⁄4, or 75 percent, majority in a referendum.[38] This ban delayed Palau's transition to independence, because while negotiating the Compact, the U.S. insisted on the option to operate nuclear propelled vessels and store nuclear weapons within the territory,[39] prompting campaigns for independence and denuclearisation.[40] After several referendums that failed to achieve a ¾ majority, the people of Palau finally approved the Compact in 1994.[41][42]

The Philippines, a neighboring ally of Palau to the west, has expressed its intent to back Palau if ever it wishes to join ASEAN.[28]

In June 2009, Palau announced that it would accept up to seventeen Uyghurs who had previously been detained by the American military at Guantanamo Bay,[43] with some American compensation for the cost of their upkeep.[44]

Only one of the Uyghurs initially agreed to resettlement,[45] but by the end of October, six of the seventeen had been transferred to Palau.[46] An aid agreement with the United States, finalized in January 2010, was reported to be unrelated to the Uyghur agreement.[47]

In 2017, Palau signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[48]

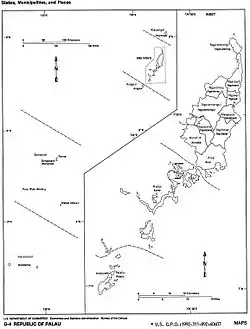

Administrative divisions

Palau is divided into sixteen States (until 1984 called municipalities). These are listed below with their areas (in square kilometres) and 2012 estimated and 2015 Census populations:

| State | Area (km2) | Population Estimate 2012 | Population Census 13 April 2015 | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.7 | 76 | 54 | comprising islands of Kayangel Atoll | |

| 11.2 | 281 | 316 | northern end of Babeldaob Island | |

| 34 | 453 | 413 | north end of Babeldaob Island, just south of Ngarchelong state | |

| 34 | 195 | 185 | on western side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 68 | 310 | 350 | on western side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 33 | 257 | 282 | on western side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 17 | 226 | 282 | on eastern side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 26 | 300 | 277 | on eastern side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 43 | 287 | 291 | on eastern side of Babeldaob Island | |

| 44 | 281 | 334 | southwest part of Babeldaob Island | |

| 59 | 2,537 | 2,455 | southeast part of Babeldaob Island | |

| 60.52 | 11,670 | 11,444 | Koror, Arakabesan and Malakal Islands, plus Rock Islands (Chelbacheb) and Eil Malk to the southwest | |

| 22.3 | 510 | 484 | comprises Peleliu Island and some islets to its north, notably Ngercheu | |

| 8.06 | 130 | 119 | Angaur Island, 12 km south of Peliliu | |

| 3.1 | 42 | 40 | comprises Sonsorol, Fanna, Pulo Anna and Merir Islands | |

| 0.9 | 10 | 25 | comprises Tobi Island and (uninhabited) Helen Reef |

Historically, Palau's Rock Islands have been part of the State of Koror. The Southwestern islands (Sonsorol and Hatohobei States) do not speak Palauan, but the distantly related Sonsorolese-Tobian (related to Woleai Atoll's Yapese)

Maritime law enforcement

Palau's Division of Marine Law Enforcement patrols the nation's 600,000 square kilometers (230,000 square miles) exclusive economic zone. They operate two long range patrol boats, the Remeliik and the Kedam, to hunt for poachers and unlicensed fishermen.[50][51][52] Smaller boats are used for littoral operations.[49] They are based on Koror.[53]

Geography

Palau's territory consists of an archipelago located in the Pacific Ocean. Its most populous islands are Angaur, Babeldaob, Koror and Peleliu. The latter three lie together within the same barrier reef, while Angaur is an oceanic island several kilometers to the south. About two-thirds of the population lives on Koror.

The coral atoll of Kayangel is north of these islands, while the uninhabited Rock Islands (about 200) are west of the main island group. A remote group of six islands, known as the Southwest Islands, some 604 kilometers (375 miles) from the main islands, make up the states of Hatohobei and Sonsorol.

Climate

Palau has a tropical rainforest climate with an annual mean temperature of 28 °C (82 °F). Rainfall is heavy throughout the year, averaging 3,800 mm (150 in). The average humidity is 82% and, although rain falls more frequently between July and October, there is still much sunshine.

Palau lies on the edge of the typhoon belt. Tropical disturbances frequently develop near Palau every year, but significant tropical cyclones are quite rare. Mike, Bopha and Haiyan are the only systems that struck Palau as typhoons on record.[54]

| Climate data for Palau Islands (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.0 (87.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.3 (81.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 271.8 (10.70) |

231.6 (9.12) |

208.3 (8.20) |

220.2 (8.67) |

304.5 (11.99) |

438.7 (17.27) |

458.2 (18.04) |

379.7 (14.95) |

301.2 (11.86) |

352.3 (13.87) |

287.5 (11.32) |

304.3 (11.98) |

3,758.3 (147.97) |

| Average rainy days | 19.0 | 15.9 | 16.7 | 14.8 | 20.0 | 21.9 | 21.0 | 19.8 | 16.8 | 20.1 | 18.7 | 19.9 | 224.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 198.4 | 194.9 | 244.9 | 234.0 | 210.8 | 168.0 | 186.0 | 176.7 | 198.0 | 179.8 | 183.0 | 182.9 | 2,357.4 |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[55] | |||||||||||||

Environment

.jpg.webp)

Palau has a history of strong environment conservation. For example, Ngerukewid islands and the surrounding area are protected under the Ngerukewid Islands Wildlife Preserve, which was established in 1956.[56]

While much of Palau remains free of environmental degradation, areas of concern include illegal dynamite fishing, inadequate solid waste disposal facilities in Koror and extensive sand and coral dredging in the Palau lagoon. As with other Pacific island nations, rising sea level presents a major environmental threat. However, according to the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research average carbon dioxide emissions per person were 58 tonnes in 2018, the highest in the world and mostly from transport.[57] Inundation of low-lying areas threatens coastal vegetation, agriculture, and an already insufficient water supply. Wastewater treatment is a problem, along with the handling of toxic waste from fertilizers and biocides.

Saltwater crocodiles are also indigenous to Palau and occur in varying numbers throughout the various mangroves and in parts of the rock islands. Although this species is generally considered extremely dangerous, there has only been one fatal human attack in Palau within modern history, and that was in the 1960s. In Palau, the largest crocodile measured 4.5 meters (14 ft 9 in).

The nation is also vulnerable to earthquakes, volcanic activity, and tropical storms. Palau already has a problem with inadequate water supply and limited agricultural areas to support its population.

On 5 November 2005, President Tommy E. Remengesau, Jr. took the lead on a regional environmental initiative called the Micronesia challenge, which would conserve 30% of near-shore coastal waters and 20% of forest land by 2020. Following Palau, the initiative was joined by the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and the U.S. territories of Guam and Northern Mariana Islands. Together, this combined region represents nearly 5% of the marine area of the Pacific Ocean and 7% of its coastline.

Palau contains the Palau tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion.[58] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.09/10, ranking it 27th globally out of 172 countries.[59]

Sanctuary

On 25 September 2009, Palau announced that it would create the world's first shark sanctuary.[60] Palau banned all commercial shark fishing within the waters of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The sanctuary protects about 600,000 square kilometers (230,000 sq mi) of ocean,[61] a similar size to France.[62][63][64] President Johnson Toribiong announced the sanctuary at a meeting of the United Nations.[62][65][66] President Toribiong proposed a worldwide ban on fishing for sharks.[62] In 2012, Palau received the Future Policy Award from World Future Council, because "Palau is a global leader in protecting marine ecosystems".[67]

Economy

Palau's economy consists primarily of tourism, subsistence agriculture and fishing. Tourist activity focuses on scuba diving and snorkeling in the islands' rich marine environment, including its barrier reefs' walls and World War II wrecks. The government is the largest employer, relying heavily on U.S. financial assistance. Business and tourist arrivals numbered some 50,000 in fiscal year 2000–2001.

The population enjoys a per capita income twice that of Micronesia as a whole. Long-term prospects for the key tourist sector have been greatly bolstered by the expansion of air travel in the Pacific, the rising prosperity of leading East Asian countries and the willingness of foreigners to finance infrastructure development.

Air service has at times been spotty. Palau Micronesia Air, Asian Spirit and Pacific Flier provided service to the Philippines and other destinations at various times during the 2000s, but all suspended service.[68] United Airlines now provides near-daily service to and from Guam, and once-weekly service to Yap. Also, Korean Air provides service three times per week to Incheon.

In November 2006, Palau Saving Bank officially announced bankruptcy. On 13 December 2006, the Palau Horizon reported that 641 depositors had been affected. Among them, 398 held less than US$5,000, with the remainder ranging from US$5,000 to US$2 million. On 12 December 79 affected people received compensation. Mr. Toribiong said, "The fund for the payout came from the balance of Palau government's loan from Taiwan." From a total of US$1 million, which originally was for assisting Palau's development, US$955,000 was left at the time of bankruptcy. Toribiong requested the Taiwanese government use the balance to repay its loans. Taiwan agreed to the request. The compensation would include those who held less than US$4,000 in an account.[69]

The income tax has three brackets with progressive rates of 9.3 percent, 15 percent, and 19.6 percent respectively. Corporate tax is four percent, and the sales tax is zero. There are no property taxes.

Major tourist draws in Palau include Rock Islands Southern Lagoon, a UNESCO world heritage site,[70] and four tentative UNESCO sites, namely, Ouballang ra Ngebedech (Ngebedech Terraces), Imeong Conservation Area, Yapease Quarry Sites, and Tet el Bad (Stone Coffin).[71]

Transportation

Palau International Airport provides scheduled direct flights with Guam, Manila, Seoul and Taipei. Palau Pacific Airways also has charter flights to and from Hong Kong and Macau. In addition, the states of Angaur and Peleliu have regular service to domestic destinations.

Freight, military and cruise ships often call at Malakal Harbor, on Malakal Island outside Koror. The country has no railways, and of the 61 km or 38 mi of highways, only 36 km or 22 mi are paved. Driving is on the right and the speed limit is 40 km/h (25 mph). Taxis are available in Koror. They are not metered and fares are negotiable. Transportation between islands mostly relies on private boats and domestic air services. However, there are some state run boats[72] between islands as a cheaper alternative.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 11,210 |

| 1980 | 12,116 |

| 1990 | 15,122 |

| 2000 | 21,000 |

The population of Palau is approximately 17,907, of whom 73% are native Palauans of mixed Melanesian, and Austronesian descent. There are many Asian communities within Palau. Filipinos form the largest Asian group and second largest ethnic group in the country, dating back to the Spanish colonial period. There are significant numbers of Chinese and Koreans. There are also smaller numbers of Palauans of mixed or full Japanese ancestry. Smaller numbers of Bangladeshi and Nepalese migrant workers and their descendants who came to the islands during the late 1900s can also be found. Most Palauans of Asian origin came during the late 1900s with many Chinese, Bangladeshis and Nepalese coming to Palau as unskilled workers and professionals.[73] There are also small numbers of Europeans and Americans.

Languages

The official languages of Palau are Palauan and English, except in two states (Sonsorol and Hatohobei) where the local languages, Sonsorolese and Tobian, respectively, along with Palauan, are official. Japanese is spoken by some older Palauans and is an official language in the State of Angaur.[74][75] Including second-language speakers, more people speak English than Palauan in Palau. Additionally, a significant portion of the population speak the Filipino language.[76]

Religion

According to 2015 estimates 45.3% of the population is Roman Catholic (due to its shared colonial heritage with the Philippines), 6.9% Seventh-day Adventist, 34.9% other Protestant (due to American colonial rule), 5.7% Modekngei and 3.0% Muslim (due to its shared Islamic heritage with southern Philippines).[1] In 2009, the small Jewish community sent two cyclists to the 18th Maccabiah Games.[77]

The German and Japanese occupations of Palau both subsidized missionaries to follow the Spanish. Germans sent Roman Catholic and Protestant, Japanese sent Shinto and Buddhist, and Spaniards sent Roman Catholic missionaries as they controlled Palau. Three quarters of the population are Christians (mainly Roman Catholics and Protestants), while Modekngei (a combination of Christianity, traditional Palauan religion and fortune telling) and the ancient Palauan religion are commonly observed. Japanese rule brought Mahayana Buddhism and Shinto to Palau, which were the majority religions among Japanese settlers. However, following Japan's World War II defeat, the remaining Japanese largely converted to Christianity, while the remainder continued to observe Buddhism, but stopped practicing Shinto rites.[78] There are also approximately 400 Bengali Muslims in Palau, and recently a few Uyghurs detained in Guantanamo Bay were allowed to settle in the island nation.

Culture

Palauan society follows a very strict matrilineal system. Matrilineal practices are seen in nearly every aspect of Palauan traditions, especially in funeral, marriage, inheritance and the passing of traditional titles. The system probably had its origins from the Philippine archipelago, which had a similar system until the archipelago was colonized by Spain.

The cuisine includes local foods such as cassava, taro, yam, potato, fish and pork. Western cuisine is favored among young Palauans and the locals are joined by foreign tourists. The rest of Micronesia is similar with much less tourism, leading to fewer restaurants. Tourists eat mainly at their hotels on such islands. Some local foods include an alcoholic drink made from coconut on the tree; the drink made from the roots of the kava; and the chewing of betel nuts.

The traditional government system still influences the nation's affairs, leading the federal government to repeatedly attempt to limit its power. Many of these attempts took the form of amendments to the constitution that were supported by the corporate sector to protect what they deemed should be free economic zones. One such example occurred in early 2010, where the Idid clan, the ruling clan of the Southern Federation, under the leadership of Bilung, the Southern Federation's queen, raised a civil suit against the Koror State Public Lands Authority (KSPLA). The Idid clan laid claim over Malakal Island, a major economic zone and Palau's most important port, citing documents from the German Era. The verdict held that the Island belonged to the KSPLA.

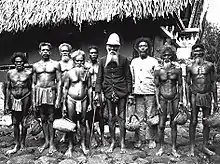

Traditional government

The present-day "traditional" government of Palau is a continuation of its predecessors. Traditionally, Palau was hierarchically organized. The lowest level is the village or hamlet, then the chiefdom (now politically referred to as a state) and finally alliances of chiefdoms. In ancient times, numerous federations divided power, but upon the 17th century introduction of firearms by the British, an imbalance of power occurred.

Palau became divided into northern and southern federations. The Northern Federation is headed by the high chief and chiefess of the ruling clan Uudes of Melekeok state, the Reklai and Ebilreklai. They are commonly referred to as the king and queen of the Northern Federation. This northern federation comprises the states of Kayangel, Ngerchelong, Ngardmau, Ngiwal, Ngaraard, Ngatpang, Ngeremlengui, Melekok, Aimeliik, Ngchesar and Airai. The Southern Federation is likewise represented by the high chief and chiefess of the ruling Idid of Koror state.

The Southern Federation comprises the states of Koror, Peleliu and Angaur. However, fewer and fewer Palauans have knowledge of the concept of federations, and the term is slowly dying out. Federations were established as a way of safeguarding states and hamlets who shared economic, social, and political interests, but with the advent a federal government, safeguards are less meaningful. However, in international relations, the king of Palau is synonymous with the Ibedul of Koror. This is because Koror is the industrial capital of the nation, elevating his position over the Reklai of Melekeok.

It is a misconception that the king and queen of Palau, or any chief and his female counterpart for that matter, are married. Traditional leaders and their female counterparts have always been related and unmarried (marrying relatives was a traditional taboo). Usually, a chief and his female counterpart are brother and sister, or close cousins, and have their own spouses.

Newspapers

Palau has several newspapers:[79][80]

- Rengel Belau (1983-1985)

- Tia Belau (1992–present)

- Island Times

Sports

Baseball is a popular sport in Palau after its introduction by the Japanese in the 1920s. The Palau national baseball team won the gold medal at the 1990, 1998 and 2010 Micronesian Games, as well as at the 2007 Pacific Games.

Palau also has a national football team, organized by the Palau Football Association, but is not a member of FIFA. The Association also organizes the Palau Soccer League.

Education

Primary education is required until the age of 16. Schools include both public and private institutions as well as some fields of study available at Palau Community College. For further undergraduate, graduate and professional programs, students travel abroad to attend tertiary institutions. Popular choices among Palauan scholars include the San Diego State University, University of the Philippines, Mindanao State University, and the University of the South Pacific.[81]

Cuisine

Palau has its own cuisine, for instance, a dessert called tama.[82] Palauan cuisine includes local foods such as cassava, taro, yam, potato, fish and pork. It is also influenced by neighboring Philippines' cuisine, notably on its Asian-Latin dishes. Fruit bat soup is a commonly referenced Palauan delicacy.[83]

References

- "Palau". The World Factbook. CIA.

- "Palau Demographics Profile". www.indexmundi.com.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Palau". www.imf.org.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Constitution of Palau Archived 26 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF). palauembassy.com. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Statistical Yearbook 2015". Republic of Palau Bureau of Budget and Planning Ministry of Finance (2016-02-01). Retrieved on 2018-08-21.

- Clark, Geoffrey; Anderson, Atholl; Wright, Duncan (2006). "Human Colonization of the Palau Islands, Western Micronesia". Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology. 1 (2): 215–232. doi:10.1080/15564890600831705. S2CID 129261271.

- Smith, Alexander D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (2): 435–490. doi:10.1353/ol.2017.0021. S2CID 149377092.

- Culture of Palau – Every Culture. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- The Bais of Belau – Underwater Colours. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Palau: Portrait of Paradise. Underwater Colours. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Palau – Historical Boys' Clothing. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Palau – Foreign Ships in Micronesia. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- Serrano, Andres (1707). Los siete principes de los Angeles: validos del Rey del cielo. Misioneros, y protectores de la Tierra, con la practica de su deuocion. por Francisco Foppens. pp. 132–.

- Francis X. Hezel, SJ, Catholic Missions in the Carolines and Marshall Islands. Micsem.org. Retrieved on 12 September 2015.

- Balabo, Dino (10 December 2006). "Historians: Malolos Congress produced best RP Constitution". Philippine Star. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- Perkins, Dorothy (1997). Japan Goes to War: A Chronology of Japanese Military Expansion from the Meiji Era to the Attack on Pearl Harbor (1868–1941). DIANE Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 9780788134272.

Admiral Takeo Takagi led the Philippines support force to Palau, an island 800 kilometers (500 miles) east of the southern Philippines where he waited to join the attack.

- "Pacific Island Battleground Now the Republic of Belau". Bangor, Maine, USA. Associated Press. 23 January 1981.

- "Palau Gains Independence on Saturday". Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Associated Press. 30 September 1994.

- Cave, Damien (5 February 2021). "Pacific Islands' Most Important Megaphone Falls Into Discord". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- "Key Pacific body in crisis as Palau walks out". France 24. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Palau - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org.

- "Tiny Island Nation's Enormous New Ocean Reserve is Official". 28 October 2015.

- "This Small Island Nation Makes a Big Case For Protecting Our Oceans". 3 April 2017.

- "Pacific island forces visitors to sign eco-pledge". South China Morning Post. 8 December 2017.

- "PH, Palau agree to enhance ties".

- "Compact of Free Association: Palau's use of and accountability for U.S. assistance and prospects for economic self-sufficiency" (PDF). Report to Congressional Committees. GAO-08-732: 1–2. 10 June 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- Compact of Free Association Between the Government of the United States of America and the government of Palau Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, preamble

- Compact of Free Association Between the Government of the United States of America and the government of Palau Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Table of Contents

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 49/63, Admission of the Republic of Palau to Membership in the United Nations, adopted 15 December 1994. Un.org. Retrieved on 12 September 2015.

- "The President of the Republic of Palau to Visit Japan". Tokyo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 15 December 2014.

- Responsibilities and Authorities. USDOI Office of Insular Affairs. doi.gov

- General Assembly – Overall Votes – Comparison with U.S. vote lists Palau as in the country with the third high coincidence of votes. Palau has always been in the top three.

- Fackler, Martin (9 April 2015). "Ahead of World War II Anniversary, Questions Linger Over Stance of Japan's Premier". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Pacific nations extend bans on tuna fishing". Radio Australia. East West Center. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "The Constitution of the Republic of Palau". The Government of Palau. 2 April 1979. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Issues Associated. With Palau's Transition to Self-Government" (PDF). Government Accountability Office. July 1989. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- Morei, Cita (1998), "Planting the mustard seed of world peace", in dé Ishtar, Zohl (ed.), Pacific women speak out for independence and denuclearisation, Christchurch, Aotearoa/New Zealand Annandale, New South Wales, Australia: Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (Aotearoa) Disarmament and Security Centre (Aotearoa) Pacific Connections, ISBN 9780473056667

- Lyons, Richard D. (6 November 1994). "Work Ended, Trusteeship Council Resists U.N. Ax for Now". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- "Trusteeship Mission reports on Palau voting. (plebiscite on the Compact of Free Association with the United States)". UN Chronicle. Vol. 27 no. 2. June 1990.

- "Pacific state Palau to take Uighur detainees". CTV News. 10 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- Kirit Radia (10 June 2009). "US and Palau wrangling over Gitmo transfer details, including $$". ABC News. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009.

- "Palau Government still not sure if Uighurs are coming". Radio New Zealand International. 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2009.

- "Six Guantanamo Uighurs arrive in Palau: US". Agence France-Presse. 31 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012.

-

"Palau receives aid boost from US". australianetworknews.com. 30 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

The president insisted there was no link to the island's hosting of six inmates from Guantanamo Bay. Palau had earlier rejected a 156 million dollar offer and the settlement came after the island nation agreed to resettle six Muslim Uighurs who had been held for more than seven years at the US naval base at Guantanamo Bay. The six arrived in Palau in November. But Johnson said the two issues were not related.

- "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

-

L.N. Reklai (25 April 2017). ""Euatel" patrol boat handover today". islandtimes.us. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

This is third in the series of patrol boats of this size donated by The Nippon Foundation to Palau. Kabekl M’tal was donated in 2012 and Bul was donated in 2014.

- Ongerung Kambes Kesolei, Tia Belau (22 December 2017). "Palau Gets New Patrol Boat". www.pacificnote.com/. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Operation Kaukledm". 8 May 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

-

Bernadette H. Carreon (3 March 2016). "Palau's maritime surveillance gets boost with new patrol boat". = www.postguam.com. Koror, Palau. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

Palau currently has a lone patrol boat, PSS H.I Remeliik, that is about 31.5 meters long. The Remeliik was donated by the Australian government in 1996. The vessel is scheduled to get an upgrade funded by the Australian government by 2018.

- Urbina, Ian (21 February 2016), "Palau vs the Poachers", The New York Times Magazine, pp. 40–49,

Nearly 9,000 miles [14,000 km] away, the Remeliik, a police patrol ship from the tiny island nation Palau, was pursuing a 10-man Taiwanese pirate ship, the Shin Jyi Chyuu 33, through Palauan waters.

- Kitamoto, Asanobu. "Tracking Chart Latitude 7.40N / Longitude 134.50E (±1)". Digital Typhoon. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Climatological Information for Palau Islands, Pacific Islands, United States". Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- Wiles, Gary J.; Conry, Paul J. (1990). "Terrestrial vertebrates of the Ngerukewid Islands Wildlife Preserve, Palau Islands". Micronesica. 23 (1): 41–66.

- Union, Publications Office of the European (26 September 2019). "Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries : 2019 report". op.europa.eu. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568.

- Grantham, H. S.; et al. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723.

- "Palau creates world's first shark haven". The Philippine Star. 26 September 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- Richard Black (25 September 2009). Palau pioneers 'shark sanctuary'. BBC News.

- "Palau's EEZ becomes shark sanctuary". Xinhua News Agency. 27 September 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- Sophie Tedmanson (26 September 2009). "World's first shark sanctuary created by Pacific island of Palau". The Times. London. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- Ker Than (25 September 2009). "France-Size Shark Sanctuary Created – A First". National Geographic. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- "Palau creates shark sanctuary to protect tourism and prevent overfishing". Radio New Zealand. 27 September 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- Cornelia Dean (24 September 2009). "Palau to Ban Shark Fishing". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- "Tiny Nation of Palau Proves Sharks Worth More Alive Than Dead". Jakarta Globe. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012.

- Ghim-Lay Yeo. "Palau's PacificFlier relooks business plan after suspension". Flightglobal. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- 李光儀、王光慈. "帛琉銀行倒閉 賠償存戶竟由台灣埋單 (Taiwan pay for the bill of compensation for PSB bankruptcy)". udn.com Center. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Rock Islands Southern Lagoon". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Palau". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- "All the Schedules and Prices for Palau's State Ferries between Koror, Peliliu and Angour". 17 February 2016.

- R. G. Crocombe (2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West. editorips@usp.ac.fj. pp. 60, 61. ISBN 978-982-02-0388-4.

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Field Listing :: Languages". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- Paul M. Lewis (ed) (2009). "Languages of Palau". SIL International. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Palau". Ethnologue.

- Sokolow, Moshe (6 December 2012). "I've Got Friends in Low-lying Places..." Jewish Ideas Daily. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

- Brigham Young University—Hawaii Campus (1981), p. 36

- Dawrs, Stu. "Research Guides: Pacific Islands Newspapers : Palau". guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- "Homepage". Island Times. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- "Palau Education System". www.classbase.com. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- "Tama – A Year Cooking the World". ayearcookingtheworld.com. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- "Fruit bat soup has chicken-like taste". Newcastle Herald. 12 June 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

External links

Government

Local News

General information

- Palau. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Palau from the University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries (USA) – Government Publications

- Palau at Curlie

- Palau profile from the BBC News

- "Palau"—Encyclopædia Britannica entry

Wikimedia Atlas of Palau

Wikimedia Atlas of Palau- NOAA's National Weather Service – Palau

- The Interesting History of Prince Lee Boo, Brought to England from the Pelew Islands—From the Collections at the Library of Congress

.svg.png.webp)