Pan Am Flight 845

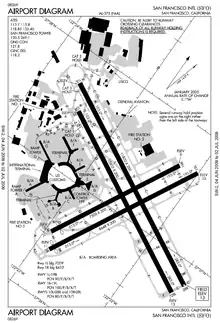

Pan Am Flight 845 was a Boeing 747-121, registration N747PA, operating as a scheduled international passenger flight between Los Angeles and Tokyo, with an intermediate stop at San Francisco International Airport (ICAO: KSFO).[1] On July 30, 1971, at 15:29 PDT, while taking off from San Francisco bound for Tokyo, the aircraft struck approach lighting system structures located past the end of the runway, seriously injuring two passengers and sustaining significant damage. The crew continued the takeoff, flying out over the ocean and circling while dumping fuel, eventually returning for a landing in San Francisco. After coming to a stop, the crew ordered an emergency evacuation, during which 27 passengers were injured while exiting the aircraft, with eight of them suffering serious back injuries.[1][2][3] The accident was investigated by the NTSB, which determined the probable cause was the pilot's use of incorrect takeoff reference speeds. The NTSB also found various procedural failures in the dissemination and retrieval of flight safety information, which contributed to the accident.[1]

_N747PA_%22Clipper_Juan_T._Trippe%22_(21493349240).jpg.webp) The aircraft involved in the accident. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | July 30, 1971 |

| Summary | Struck structures past runway on takeoff due to pilot error |

| Site | San Francisco Int'l Airport San Mateo County, California United States |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747-121 |

| Aircraft name | Clipper America Later: Clipper Sea Lark Clipper Juan T. Trippe |

| Operator | Pan Am |

| Registration | N747PA |

| Flight origin | Los Angeles, California |

| Stopover | San Francisco Int'l Airport |

| Destination | Haneda International Airport, Japan |

| Occupants | 218 |

| Passengers | 199 |

| Crew | 19 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 29 |

| Survivors | 218 |

Aircraft and crew

The Boeing 747-121, registration N747PA, manufacturing serial number 19639, first flew on April 11, 1969 and was delivered to Pan Am on October 3, 1970. It was the second 747 off Boeing's production line but wasn't delivered until nearly ten months after Pan Am's first 747 flight. Originally named Clipper America it had logged 2,900 hours of operation at the time of the accident.[1][4]

The flight crew of Flight 845 consisted of five (a captain, a first officer, a flight engineer, a relief flight engineer and a relief pilot). The captain was Calvin Y. Dyer, a 57-year-old resident of Redwood City, California, a pilot with 27,209 hours' flying experience, 868 of which were on the 747. The first officer was Paul E. Oakes, a 41-year-old resident of Reno, Nevada, with 10,568 hours' experience, 595 on the 747. The flight engineer was Winfree Horne, he was 57 years old and from Los Altos, California, he had 23,569 hours' flight experience, 168 on the 747. 34-year-old Second officer Wayne E. Sagar was the relief pilot he had 3,230 hours of flight experience, 456 on the 747. The relief flight engineer was Roderic E. Proctor, a 57-year-old resident of Palo Alto, California, he had 24,576 flight hours, 236 on the 747.

On July 29, 1971, Dyer, Oakes, Horne, Sagar and Proctor had spent the whole day off-duty. They had also flown the initial Los Angeles to San Francisco leg of the flight.

Accident history

Flight 845's crew had planned and calculated their takeoff for runway 28L, but discovered only after pushback that this runway had been closed hours earlier for maintenance,[6] and that the first 1,000 feet (300 m) of runway 01R, the preferential runway at that time,[7] had also been closed. After consulting with Pan Am flight dispatchers and the control tower, the crew decided to take off from runway 01R, shorter compared to 28L, with less favorable wind conditions.[8]

Runway 01R was about 8,500 feet (2,600 m) long from its displaced threshold (from which point the takeoff was to start) to the end, which was the available takeoff length for Flight 845.[9] Because of various misunderstandings, the flight crew was erroneously informed the available takeoff length from the displaced threshold was 9,500 feet (2,900 m), or 1,000 feet (300 m) longer than actually existed. Despite the shorter length, it was later determined that the aircraft could have taken off safely, had the proper procedures been followed.

As the crew prepared for takeoff on the shorter runway, they selected 20 degrees of flaps instead of their originally planned 10 degree setting, but did not recalculate their takeoff reference speeds (V1, Vr and V2), which had been calculated for the lower flap setting, and were thus too high for their actual takeoff configuration.

Consequently, these critical speeds were called late and the aircraft's takeoff roll was abnormally prolonged. In fact the first officer called Vr at 160 knots (184 mph; 296 km/h) instead of the planned 164 knots (189 mph; 304 km/h) because the end of the runway was "coming up at a very rapid speed."[10]

Damage

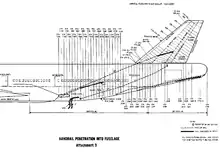

Unable to attain sufficient altitude to clear obstructions at the end of the runway, the aircraft's aft fuselage, landing gear and other structures were damaged as it struck components of the approach lighting system (ALS) at over 160 knots (180 mph; 300 km/h). Three lengths of angle iron up to 17 feet (5.2 m) penetrated the cabin, injuring two passengers. The right main under-body landing gear was forced up and into the fuselage, and the left under-body landing gear was ripped loose and remained dangling beneath the aircraft. Other systems damaged in the impact included Nos 1, 3, and 4 hydraulic systems, several wing and empennage control surfaces and their mechanisms, electrical systems including the antiskid control, and three of the evacuation slides.

The flight proceeded out over the Pacific Ocean for one hour and 42 minutes to dump fuel in order to reduce weight for an emergency landing. During this time, damage to the aircraft was assessed and the injured treated by doctors on the passenger list. After dumping fuel, the aircraft returned to the airport. Emergency services were deployed and the plane landed on runway 28L. During landing, six tires on the under-wing landing gear failed. Reverse thrust functioned only on engine 4, so the aircraft slowly veered to the right, off the runway and came to a stop. The left under-wing landing gear caught fire, although this fire was extinguished by dirt once the plane veered off the runway.[11] After stopping, the aircraft slowly tilted backwards due to the missing body gear, which had been ripped off or disabled on takeoff. The aircraft came to rest on its tail with its nose elevated. Until this accident it was not known that the 747 would tilt backwards without the support of the main body gear.

Injuries

There were no fatalities among the 218 passengers and crew aboard, but two passengers were seriously injured during the impact, and during the subsequent emergency evacuation twenty-seven more sustained injuries, eight of them serious.

Rods of angle iron from the ALS structure penetrated the passenger compartment, injuring passengers in seats 47G (near amputation of left leg below the knee) and 48G (severe laceration and crushing of left upper arm).

After landing, the aircraft veered off the runway on its damaged landing gear and came to a halt. Evacuation commenced from the front due to a failure to broadcast the evacuation order over the cabin address system (it was erroneously broadcast over the radio), the order being given by one of the flight crew exiting the cockpit and noticing that evacuation had not commenced. During this time, the aircraft settled aft, resting on its tail in a nose-up attitude. The four forward slides were unsafe for use due to the greater elevation and high winds. Most passengers evacuated from the rear six slides. Eight passengers using the forward slides sustained serious back injuries and were hospitalised. Other passengers suffered minor injuries such as abrasions and sprains.

Investigation

The accident was investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which issued its final report on May 24, 1972. According to the NTSB, the Probable Cause of the accident was:[3]

... the pilot's use of incorrect takeoff reference speeds. This resulted from a series of irregularities involving: (1) the collection and dissemination of airport information; (2) aircraft dispatching; and (3) crew management and discipline; which collectively rendered ineffective the air carrier's operational control system.

Aftermath

Subsequent to the accident, the aircraft was repaired and returned to service. N747PA was re-registered and leased to Air Zaïre as N747QC from 1973 until March 1975, when returned to Pan Am, where it was renamed Clipper Sea Lark, and then Clipper Juan T. Trippe in honor of the airline's founder.[2] It remained with Pan Am until the airline ceased operations in 1991, and was transferred to Aeroposta, then briefly to Kabo Air of Nigeria, back to Aeroposta, and was finally cut into pieces in 1999 at Norton AFB in San Bernardino, California where it had been stored since at least 1997.

The parts of the aircraft were shipped to Hopyeong, Namyangju, South Korea and reassembled, to serve as a restaurant for some time, until it closed down. After the restaurant shut down, there were petitions and campaigns from numerous aviation enthusiasts for museums or local governments to preserve the historical airplane. Part of the aircraft was scrapped in 2010 however, three major pieces of fuselage were saved and moved not far away to the suburb of Wolmuncheon-ro. The former aircraft is now reported to be used as a church. (Location:1052-7 Wolmun-ri, Wabu-eup, Namyangju-si, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea).[12][13][14][15][16]

- "NTSB final report" (PDF). NTSB. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- Thompson, Nigel; Ricky-Dene Halliday, eds. (1984). Airliner Production List 1984/85. London: Aviation Data Centre. p. 231. ISBN 0-946141-09-6.

- "ASN accident record". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- "Boeing 747 complete production list". airfleets.net. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- Comparing the 1971 runway orientations and lengths described in the NTSB report to the modern ones, only runway 28R has been significantly changed. (See p. 10, NTSB report.)

- Crews were repairing a crack which appeared in the pavement that morning.

- Due to noise abatement.

- Runway 28L was 10,600 feet (3,200 m) long, and the wind was from the west at 22 knots (41 km/h). (See NTSB report, p. 10.)

- Boeing 747 aircraft were not authorized to apply takeoff thrust before reaching the displaced threshold of runway 01R, to reduce jetblast effects on a nearby highway (see NTSB report).

- The most critical reference speed is Vr, which is when the pilot flying (pilot manipulating the controls, in this flight the captain) "rotates" (lifts the aircraft's nose); if rotation is done too late in the takeoff roll, the climb will be delayed and obstruction clearance reduced.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tl_wXfSwRzM

- "Aeroposta N747PA (ex N747QC)". Airfleets.

- "Picture of the Boeing 747-121 aircraft". Airliners.net. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- "N747PA rusting away". PPRuNe. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- Glionna, John M. (2010-12-13). "Historic 747 reaches grim end in South Korea". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- Diamond, Cody (2017-12-03). "Finding the Clipper Juan T. Trippe – In 2017". Airways Magazine. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

See also

- Emirates Flight 407

- MK Airlines Flight 1602, an almost identical accident involving a Boeing 747 which occurred 33 years later, albeit with fatalities.

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft