Parergon

Parergon (paˈrərˌgän, plural: parerga[2]) is an ancient Greek philosophical concept defined as a supplementary issue.[3] Parergon is also referred to as "embellishment" or extra.[4]

.jpg.webp)

The literal meaning of the ancient Greek term is "beside, or additional to the work".[5] According to Jacques Derrida, it is "summoned and assembled like a supplement because of the lack - a certain 'internal indetermination - in the very thing it enframes".[6] It is added to a system to augment something lacking such as in the case of ergon (function, task or work), with parergon constituting an internal structural link that makes its unity possible.[6]

Concept

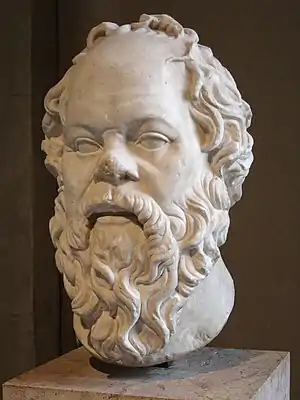

Parergon is viewed negatively, particularly within Greek classical thought, since it is against ergon or the true matter.[7] Socrates used parergon to refer to the violation of the Athenian rule of "one man, one job", criticizing supplementary occupations that keep the citizens from specialization and works they are naturally fitted.[3] His criticism also stemmed from the accusation that philosophy is a type of parergon. In the Republic, he explained that paideia – the rearing and education of the ideal member of the polis or state – must not be considered equivalent to parergon. The emphasis stems from the perception that both connote a relationship to the essential function, expressed in a rigorous definition.[3] The Socratic dialogue established that paideia does not indicate the possibility of changing the main issue and does not indicate marginality but these were identified as characteristics of parergon.[3]

Plato considered parergon as something that is secondary and that his philosophical discourse is often against it, explaining how it is against and beyond the ergon, conceptualized as the work accomplished.[8] Parergon was included in Plato's work Laws, where it was compared with the concepts of paideia and deuteron.[3] These two terms were both cited as superior in importance in the sense that they must be taken more seriously than parergon.

In Greek philosophy, however, parergon is not considered incidental.[8]

Modern descriptions

Immanuel Kant also used parergon in his philosophy. In his works, he associated it with ergon, which in his view is the "work" of one's field (e.g. work of art, work of literature, and work of music, etc.). According to Kant, parergon is what is beyond ergon.[9] It is what columns are to buildings or the frame to a painting. He provided three examples of parergon: 1) clothing on a statue; 2) columns on a building; and, 3) the frame of a painting.[10] He likened it to an ornament, one that primarily appeals to the senses.[11] Kant's conceptualization influenced Derrida's usage of the term, particularly how it served as an agent of deconstruction using Kant's conceptualization of the painting's frame.

Parergon is also described as separate - that it is detached not only from the thing it enframes but also from the outside (the wall where a painting is hung or the space in which the object stands).[8] This conceptualization underscores the significance of parergon for thinkers such as Derrida and Heidegger as it makes the split in the duality of intellect/senses.[11] It plays an important rule in aesthetic judgment if it augments the pleasure of taste. It diminishes in value if it is not formally beautiful, lapsing as a simple adornment.[12] According to Kant, this case is like a gilt frame of a painting, a mere attachment to gain approval through its charm and could even detract from the genuine beauty of the art.[13]

Derrida cited parergon in his wider theory of deconstruction, using it with the term "supplement" to denote the relationship between the core and the periphery and reverse the order of priority so that it becomes possible for the supplement – the outside, secondary and inessential – to be the core or the centerpiece.[14] In The Truth in Painting, the philosopher likened parergon with the frame, borders, and marks of boundaries, which are capable of "unfixing" any stability so that conceptual oppositions are dismantled.[1] It is, for the philosopher, "neither work (ergon) nor outside work", disconcerting any opposition while not remaining indeterminate.[15] For Derrida, parergon is also fundamental, particularly to the ergon since, without it, it "cannot distinguish itself from itself".[7]

In artistic works, parergon is viewed as separate from an artwork it frames but merges with the milieu, which allows it to merge with the work of art.[16]

In a book, parergon can be the liminal devices that mediate it to its reader such as title,[17] foreword, epigraph, preface, etc.[16] It can also be a short literary piece added to the main volume such as the case of James Beattie's The Castle of Scepticism. This is an allegory written as a parergon and was included in the philosopher's main work called Essay on truth, which criticized David Hume, Voltaire, and Thomas Hobbes.[18]

References

- Reynolds, Jack; Roffe, Jonathan (2004). Understanding Derrida. New York: Continuum. p. 88. ISBN 0826473156.

- "Definition of PARERGON". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- Statkiewicz, Max (2009). Rhapsody of Philosophy: Dialogues with Plato in Contemporary Thought. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780271035406.

- Battersby, Christine (2007). The Sublime, Terror and Human Difference. Oxon: Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9780415148108.

- Schacter, Rafael (2016-05-13). Ornament and Order: Graffiti, Street Art and the Parergon. Routledge. ISBN 9781317084990.

- Rodowick, David (2001). Reading the Figural, Or, Philosophy After the New Media. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780822327226.

- Neel, Jasper (2016). Plato, Derrida, and Writing. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780809335152.

- Culler, Jonathan D. (2003). Deconstruction: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies, Volume II. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 45, 46. ISBN 041524708X.

- O'Halloran, Kieran (2017). Posthumanism and Deconstructing Arguments: Corpora and Digitally-driven Critical Analysis. Oxon: Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 9780415708777.

- Richards, K. Malcolm (2013-02-05). Derrida Reframed: Interpreting Key Thinkers for the Arts. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857718907.

- Minissale, Gregory (2009). Framing Consciousness in Art: Transcultural Perspectives. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 92. ISBN 978-90-420-2581-3.

- Ross, Stephen David (1994). Art and Its Significance: An Anthology of Aesthetic Theory, Third Edition. New York: SUNY Press. pp. 415. ISBN 978-0-7914-1852-9.

- Battersby, Christine (2007). The Sublime, Terror and Human Difference. Oxon: Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9780415148108.

- Marder, Michael (2014). The Philosopher's Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780231169028.

- Fuery, Patrick (2000). New Developments in Film Theory. London: Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 153. ISBN 9780333744901.

- Trotter, David (2013). Literature in the First Media Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-674-07315-9.

- Pedri, Nancy; Petit, Laurence (2014). Picturing the Language of Images. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4438-5438-2.

- Landa, Louis A. (2015). English Literature, Volume 2: 1939-1950. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 1122. ISBN 978-1-4008-7733-1.