Parteniy Zografski

Partenij Zografski (Bulgarian: Партений Зографски; Macedonian: Партенија Зографски; 1818 – February 7, 1876) was a 19th-century Bulgarian cleric, philologist, and folklorist from Galičnik in today's North Macedonia, one of the early figures of the Bulgarian National Revival.[1][2] In his works he referred to his language as Bulgarian and demonstrated a Bulgarian spirit, though besides contributing to the development of the Bulgarian language,[3][4][5] In North Macedonia he is also thought to have contributed to the foundation of the Macedonian language.[6] Because in many documents of 19th century the Macedonian Slavs were referred to as "Bulgarian", Macedonian scientists argue that they were "Macedonian", regardless of what is written in the records.[7]

Biography

Religious activity

Zografski was born as Pavel Vasilkov Trizlovski (Павел Василков Тризловски) in Galičnik, then in the Ottoman Empire and today in North Macedonia. He first studied at the Saint Jovan Bigorski Monastery, then he moved to Ohrid in 1836, where he was taught by Bulgarian educator Dimitar Miladinov; he also studied at the Greek schools in Thessaloniki and Istanbul. Trizlovski became a monk at the Bulgarian Zograf Monastery on Mount Athos, where he acquired his clerical name. Zografski continued his education at the seminary in Odessa, Russian Empire; he then joined the Căpriana monastery in Moldavia. He graduated from the Kiev seminary in 1846 and from the Moscow seminary in 1850. He was briefly a priest at the Russian church in Istanbul until he established a clerical school at the Zograf Monastery in 1851 and taught there until 1852. From 1852 to 1855, he was a teacher of Church Slavonic at the Halki seminary; from 1855 to 1858, he held the same position at the Bulgarian school in Istanbul, also serving at the Bulgarian and Russian churches in the imperial capital.

On 29 October 1859, at the request of the Bulgarian Municipality of Kukush (Kilkis), the Patriarchate appointed Zografski Metropolitan of Dojran in order to counter the rise of the Eastern Catholic Macedonian Apostolic Vicariate of the Bulgarians. Parteniy Zografski co-operated with the locals to establish Bulgarian schools and increase the use of Church Slavonic in liturgy. In 1861, the Greek Orthodox Church Metropolitan of Thessaloniki and a clerical court prosecuted him, but he was acquitted in 1863. In 1867, he was appointed Metropolitan of Nishava in Pirot. At this position, he supported the Bulgarian education in these regions and countered the Serbian influence.[8] From 1868 on, Parteniy Zografski broke away from the Patriarchate and joined the independent Bulgarian clergy. After the official establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate he remained a Bulgarian Metropolitan of Pirot until October 1874, when he resigned.

Linguistic activity

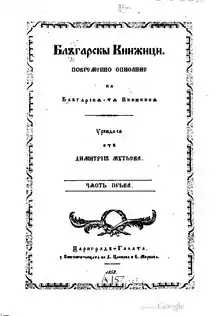

Besides his religious activity, Zografski was also an active man of letters. He co-operated with the Bulgarian Books magazine and the first Bulgarian newspapers: Savetnik, Tsarigradski Vestnik and Petko Slaveykov's Makedoniya. In 1857, he published a Concise Holy History of the Old and New Testament Church. The following year he published Elementary Education for Children in Macedonian vernacular. In his article Thoughts about the Bulgarian language published in 1858 he argues that it is the Macedonian dialect that should represent the basis for the common modern "Macedono-Bulgarian" literary standard, called simply Bulgarian.[9]

Our language, as it is well known, is divided into two main dialects, of which one is spoken in Bulgaria and Thrace, and the other one in Macedonia... To promote to the world the Macedonian dialect with all its general and local idioms, as much as we can, we intend to create a Grammar for it, in parallel with the other one... The first and biggest difference between the two dialects is, in our opinion, is the difference in pronunciation or the stress. The Macedonian dialect usually prefers to place the stress in the beginning of the words, and the other one in the end, so in the first dialect you can’t find a word with a stress on the last syllable, while in the latter in most cases the stress is on the last syllable. Here Macedonian dialect is approaching the Serbian dialect...Not only that the Macedonian dialect should not and cannot be excluded from the common standard language, but it would have been good if it was accepted as its main constituent.[10]

In 1870 Marin Drinov, who played a decisive role in the standardization of the Bulgarian language, rejected the proposal of Parteniy Zografski and Kuzman Shapkarev for a mixed eastern and western Bulgarian/Macedonian foundation of the standard Bulgarian language, stating in his article in the newspaper Makedoniya: "Such an artificial assembly of written language is something impossible, unattainable and never heard of."[11][12][13]

Macedonian literary scholars maintain Zografski’s literary works published in western Macedonian vernacular make him a leading representative of the "Macedonian National Rebirth". Father Partenij wish of using the western Macedonian vernacular as the basis for a standard Bulgarian language is interpreted by the Macedonian literary scholars as a two-way Bulgaro-Macedonian compromise, not unlike the one achieved by Serbs and Croats with the 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement.[14] On the other hand Zografski, who was Bulgarian teacher and bishop, regarded his vernacular as a version of Bulgarian. He called the Macedonian dialects Lower Bulgarian and the region of Macedonia Old Bulgaria. On that base Bulgarian literary scholars, maintain that his idea about a common literary standard was not for compromise between Bulgarian and Macedonian languages, as Macedonian authors claim, but about a common language for all the Bulgarians.[15] However historians from North Macedonia maintain the designation Bulgarian used by Zografski meant in fact Macedonian.[16] Macedonian researchers claim that the term "Bulgarian" at that time was not used as an ethnic designation.[17]

Zografski died in Istanbul on 7 February 1876 and was buried in the Bulgarian St. Stephen Church.

External links

- Енциклопедия България, том 5, Издателство на БАН, София, 1986.

- "Житие и исповедание и за некои чудеса повествование иже во святих отца нашего Климента Архиепископа болгарскаго”, публикувано в сп. "Български книжици", книга 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, Цариград, 1858 година - The first Bulgarian translation of the "Life of Clement of Ohrid", was published by Parteniy Zografski in the "Bulgarski Knizhitsi" magazine in 1858.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parthenius of Zograf. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Parteniy Zografski |

Notes

- Freedom or Death, The Life of Gotsé Delchev by Mercia MacDermott, Journeyman Press, London & West Nyack, 1978, p. 22.

- A letter from Egor P. Kovalevski, Moscow, to Alexei N. Bekhmetev, Moscow, about the aid to be sent to the Bulgarian school in Koukush,1859

- Зографски, Партений. Мисли за българския език, Български книжици, 1/1858, с. 35-42 (Zografski, Pertenie. Thoughts about Bulgarian language, magazine "Bulgarian letters", 1/1858, p. 35-42)

- Grammars and dictionaries of the Slavic languages from the Middle Ages up to 1850: an annotated bibliography, Edward Stankiewicz, Walter de Gruyter, 1984, p. 71., ISBN 3-11-009778-8

- ...It is obvious that in the Bulgarian milieu, under the direct influence of Vasil Aprilov, he developed a pro-Bulgarian spirit... See: Institute for National history, Towards the Macedonian Renaissance, (Macedonian Textbooks of the Nineteenth Century) The activities of Parteni Zografski by Blaze Koneski, Skopje - 1961. Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Trencsényi, Balázs (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): texts and commentaries,. Central European University Press. pp. 255–257. ISBN 963-7326-52-9.

- Ulf Brunnbauer, “Serving the Nation: Historiography in the Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) after Socialism“, Historien, Vol. 4 (2003-4), pp. 161-182.

- Кирил Патриарх Български, 100 години от учредяването на Българската Екзархия: сборник статии. Синодално изд-во, 1971, стр. 212.

- Bechev, Dimitar. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. 2009; p. 134. ISBN 0-8108-6295-6.

- Thoughts about the Bulgarian language.

- Makedoniya July 31st 1870

- Tchavdar Marinov. In Defense of the Native Tongue: The Standardization of the Macedonian Language and the Bulgarian-Macedonian Linguistic Controversies. in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004250765_010 p. 443

- Благой Шклифов, За разширението на диалектната основа на българския книжовен език и неговото обновление. "Македонската" азбука и книжовна норма са нелегитимни, дружество "Огнище", София, 2003 г. . стр. 7-10.

- Bechev, Dimitar. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. 2009; p. 245. ISBN 0-8108-6295-6.

- Tchavdar Marinov. In Defense of the Native Tongue: The Standardization of the Macedonian Language and the Bulgarian-Macedonian Linguistic Controversies. in Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004250765_010 p. 441.

- Lucian Leustean as ed., Orthodox Christianity and Nationalism in Nineteenth-century Southeastern Europe, Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 0823256065, p. 257.

- Chris Kostov, Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900-1996, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 92.