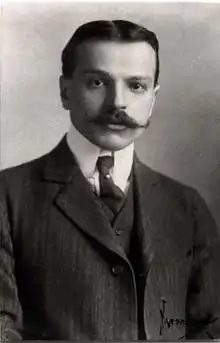

Paul Philippe Cret

Paul Philippe Cret (October 24, 1876 – September 8, 1945) was a French-born Philadelphia architect and industrial designer. For more than thirty years, he taught a design studio in the Department of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Biography

Born in Lyon, France, Cret was educated at that city's École des Beaux-Arts, then in Paris, where he studied at the atelier of Jean-Louis Pascal. He came to the United States in 1903 to teach at the University of Pennsylvania.[1] Although settled in America, he happened to be in France at the outbreak of World War I. He enlisted and remained in the French army for the duration, for which he was awarded the Croix de Guerre and made an officer in the Legion of Honor.

.jpg.webp)

Cret's practice in America began in 1907. His first major commission, designed with Albert Kelsey, was the Pan American Union Building (the headquarters of what is now the Organization of American States) in Washington DC (1908–10),[2] a breakthrough that led to many war memorials, civic buildings, court houses, and other solid, official structures.

His work through the 1920s was firmly in the Beaux-Arts tradition, but with the radically simplified classical form of the Folger Shakespeare Library (1929–32), he flexibly adopted and applied monumental classical traditions to modernist innovations. Some of Cret's work is remarkably streamlined and forward-thinking, and includes collaborations with sculptors such as Alfred Bottiau and Leon Hermant. In the late 1920s the architect was brought in as design consultant on Fellheimer and Wagner's Cincinnati Union Terminal (1929–33), the high-water mark of Art Deco style in the United States. He became an American citizen in 1927.

In 1931, the regents of The University of Texas at Austin commissioned Cret to design a master plan for the campus, and build the Beaux-Art Main Building (1934–37), the university's signature tower. Cret would go on to collaborate on about twenty buildings on the campus. In 1935, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member, and became a full Academician in 1938.

Cret's contributions to the railroad industry also included the design of the side fluting on the Burlington's Pioneer Zephyr (debuted in 1934) and the Santa Fe's Super Chief (1936) passenger cars.[3]

He was a contributor to Architectural Record, American Architect, and The Craftsman. He penned the article "Animals in Christian Art" for the Catholic Encyclopedia.[4]

Cret won the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects in 1938.[5] Ill health forced his resignation from teaching in 1937. He served on the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts from 1940 to 1945.[6] After years of limited activity, Cret died in Philadelphia of heart disease and was interred at The Woodlands Cemetery.[7]

Cret's work was displayed in the exhibit, From the Bastille to Broad Street: The Influence of France on Philadelphia Architecture, at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia in 2011. An exhibit of his train designs, All Aboard! Paul P. Cret's Train Designs, was at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia from July 5, 2012 to August 24, 2012. With a collection of 17,000 drawings and more than 3,000 photographs, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia has the largest archive of Paul P. Cret materials.

Legacy

Cret taught in the Department of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania for over 30 years, and designed such projects as the Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, the master plan for the University of Texas in Austin, the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Philadelphia, and the Duke Ellington Bridge in Washington, DC. Louis Kahn studied at the University of Pennsylvania under Cret, and worked in Cret's architectural office in 1929 and 1930. Other notable architects who studied under Cret include Alfred Easton Poor,[8] Charles I. Barber,[9] William Ward Watkin,[10] Edwin A. Keeble, and Chinese architect Lin Huiyin.[11]

Cret designed war memorials, including the National Memorial Arch at Valley Forge National Historical Park (1914–17), the Pennsylvania Memorial at the Meuse-Argonne Battlefield in Varennes-en-Argonne, France (1927), the Chateau-Thierry American Monument in Aisne, France (1930), the American War Memorial at Gibraltar, and the Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial in Waregem, Belgium (1937).[12] On the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated Cret's Eternal Light Peace Memorial (1938).

For the Pennsylvania Historical Commission, predecessor of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), Cret designed plaques that would mark places and buildings within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania where historical events transpired.[13]

Following Cret's death in 1945, his four partners assumed the practice under the partnership Harbeson, Hough, Livingston & Larson, which for years was referred to by staff members as H2L2. The firm officially adopted this "nickname" as its formal title in 1976. H2L2 celebrated 100 years in 2007.

Witold Rybczynski has speculated that Cret is not better known today due to his influence on fascist and Nazi architecture, such as Albert Speer's Zeppelinfeld at the Nuremberg Nazi party rally grounds.[14]

Major projects

- 1908–09 – Stock Pavilion, Madison, Wisconsin (with Warren Laird and Arthur Peabody)

- 1908–10 – Organization of American States Building, Washington, D.C. (with Albert Kelsey)

- 1914–17 – National Memorial Arch, Valley Forge National Historical Park, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania

- 1916–17 – Indianapolis Central Library, Indianapolis, Indiana (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary)

- 1922–26 – Benjamin Franklin Bridge, Philadelphia – Camden, New Jersey

- 1923–25 – Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania

- 1923–27 – Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary)

- 1926–29 – Rodin Museum, Philadelphia (with Jacques Gréber)

- 1928–29 – George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge, Louisville, Kentucky

- 1929 – Integrity Trust Company Building, Philadelphia

- 1929 – World War I Memorial, Providence, Rhode Island

- 1929–32 – Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

- 1930 – Chateau-Thierry American Monument, Aisne, France

- 1930–32 – Henry Avenue Bridge over Wissahickon Creek, Philadelphia

- 1931–32 – Connecticut Avenue Bridge over Klingle Valley, Washington, D.C.

- 1932 – Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 925 Chestnut St., Philadelphia

- 1932–33 Hershey Community Center Building, Hershey, Pennsylvania

- 1933 – United States Courthouse, consulting architect, Fort Worth, Texas

- 1933–34 – Central Heating Plant, Washington, D.C.

- 1934–37 – Main Building, University of Texas

- 1934–38 – Tygart River Reservoir Dam, near Grafton, West Virginia

- 1935 – Duke Ellington Bridge, Washington, D.C.

- 1935–37 – Eccles Building, Washington, D.C.

- 1935–37 – Hipolito F. Garcia Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, San Antonio, Texas

- 1936 – Dallas Fair Park, Texas Centennial Exposition Buildings at the Texas Centennial Exposition, consulting architect, Dallas

- 1936–39 – Texas Memorial Museum, consulting architect, Austin, Texas

- 1937 – Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial, Waregem, Belgium (with Jacques Gréber)

- 1938 – Eternal Light Peace Memorial, Gettysburg Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Lee Lawrie, sculptor

- 1939–44 – National Naval Medical Center, Buildings 1 and 17, consulting architect, Bethesda, Maryland

- 1940 – 2601 Parkway, Philadelphia

Gallery

Pan-American Union (now Organization of American States), Washington, DC (1908–10), (with Albert Kelsey)

Pan-American Union (now Organization of American States), Washington, DC (1908–10), (with Albert Kelsey) National Memorial Arch, Valley Forge National Historical Park, Valley Forge, PA (1914–17)

National Memorial Arch, Valley Forge National Historical Park, Valley Forge, PA (1914–17)_from_War_Memorial_Plaza.jpg.webp) Indianapolis Central Library, Indianapolis, IN (1916–17), (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary)

Indianapolis Central Library, Indianapolis, IN (1916–17), (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary) Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI (1923–27), (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary)

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI (1923–27), (with Zantzinger, Borie and Medary) Rodin Museum, Philadelphia (1926–29), Jacques Gréber, landscape architect

Rodin Museum, Philadelphia (1926–29), Jacques Gréber, landscape architect Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC (1929–32)

Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC (1929–32) Cincinnati Union Terminal, Cincinnati, OH (1929–33), (with Fellheimer & Wagner)

Cincinnati Union Terminal, Cincinnati, OH (1929–33), (with Fellheimer & Wagner) Henry Avenue Bridge over Wissahickon Creek, Philadelphia (1930–32)

Henry Avenue Bridge over Wissahickon Creek, Philadelphia (1930–32) Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (1932)

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia (1932) Central Heating Plant, Washington, DC (1933–34)

Central Heating Plant, Washington, DC (1933–34) Main Building, University of Texas, Austin, TX (1934–37)

Main Building, University of Texas, Austin, TX (1934–37) Tygart River Reservoir Dam, near Grafton, WV (1934–38)

Tygart River Reservoir Dam, near Grafton, WV (1934–38) In 1935, Cret designed the seal for the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

In 1935, Cret designed the seal for the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial, Waregem, Belgium (1937), Jacques Gréber, landscape architect

Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial, Waregem, Belgium (1937), Jacques Gréber, landscape architect Bethesda Naval Hospital Tower (aka Building 1), Bethesda, MD (1939–42). President Franklin D. Roosevelt picked the location and drew a rough plan and sketches for this building.[15]

Bethesda Naval Hospital Tower (aka Building 1), Bethesda, MD (1939–42). President Franklin D. Roosevelt picked the location and drew a rough plan and sketches for this building.[15]

References

- White, Theo B., editor, John F Harbeson, forward, Paul Philippe Cret: Author and Teacher, The Art Alliance Press, Philadelphia PA 1973 p 21

- Scott, Pamela and Antoinette J. Lee, Buildings of the District of Columbia, Oxford University Press, New York, 1991 p 208

- Johnston, Bob; Welsh, Joe; Schafer, Mike (2001). The Art of the Streamliner. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-58663-146-8.

- "Cret, Paul Philippe", The Catholic Encyclopedia and Its Makers, New York, the Encyclopedia Press, 1917, p. 36

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Wilson, Richard Guy, The AIA Gold Medal, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1984 p 162

- Thomas E. Luebke, ed., Civic Art: A Centennial History of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, 2013): Appendix B, p. 542.

- "Paul Philippe Cret". www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Art of the Print – Alfred Easton Poor. Retrieved: 17 May 2011.

- Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission, Lyons View Pike Historic District, c. 2002. Retrieved: 16 May 2011.

- Handbook of Texas Online – William Ward Watkin

- Peter G. Rowe, Seng Kuan, Architectural Encounters With Essence and Form in Modern China, MIT Press, 2002, p. 48.

- Nishiura, Elizabeth, editor, American Battle Monuments: A Guide to Military Cemeteries and Monuments Maintained By the American Battle Monuments Commission, Omnigrap p 22, 49, 50, 82

- Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine, Volume XL, Number 4, Fall 2014, A Century of Marking History: 100 Years of the PA Historical Marker Program, by John K. Robinson and Karen Galle

- Rybczynski, Witold (21 October 2014). "The Late, Great Paul Cret". T: The New York Times Style Magazine. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Maryland Historical Trust

External links

![]() Media related to Paul Philippe Cret at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Paul Philippe Cret at Wikimedia Commons

- Paul Philippe Cret biography at University of Pennsylvania

- Paul Philippe Cret Papers, University of Pennsylvania

- Paul Philippe Cret at Find a Grave

- Paul Cret – Architect on YouTube

- Paul Philippe Cret from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- Works by or about Paul Philippe Cret in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- First chapter of "The Civic Architecture of Paul Cret"

- Paul Philippe Cret architectural drawings, circa 1901-1936. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.