Pavilion

The word is from French pavillon (Old French paveillon), from Latin papilionem (accusative of papilio). In Late Latin and Old French, it meant both ‘butterfly’ and ‘tent’, because the canvas of a tent resembled a butterfly's spread wings.[2][3]

In architecture, pavilion has several meanings:

- It may be a subsidiary building that is either positioned separately or as an attachment to a main building. Often it is associated with pleasure.[1] In palaces and traditional mansions of Asia, there may be pavilions that are either freestanding or connected by covered walkways, as in the Forbidden City (Chinese pavilions), Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, and in Mughal buildings like the Red Fort.

- As part of a large palace, pavilions may be symmetrically placed building blocks that flank (appear to join) a main building block or the outer ends of wings extending from both sides of a central building block, the corps de logis. Such configurations provide an emphatic visual termination to the composition of a large building, akin to bookends.

Free-standing structures

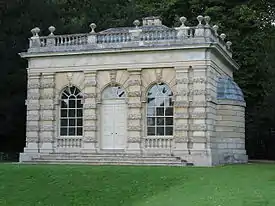

Pavilions may be small garden outbuildings, similar to a summer house or a kiosk; small rooms on the roof of a large house, reached only via the roof (rather than by internal stairs) may also be called pavilions. These were particularly popular up to the 18th century and can be equated to the Italian casina, formerly rendered in English "casino". These often resembled small classical temples and follies. Especially if there is some space for food preparation, they may be called a banqueting house. A pavilion built to take advantage of a view may be referred to as a gazebo. Bandstands in a park are a class of pavilion. A poolhouse by a swimming pool may have sufficient character and charm to be called a pavilion. By contrast, a free-standing pavilion can also be a far larger building such as the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, which is in fact a large Indian-style palace; however, like its smaller namesakes, the common factor is that it was built for pleasure and relaxation.

A sports pavilion is usually a building adjacent to a sports ground used for changing clothes and often partaking of refreshments. Often it has a verandah to provide protection from the sun for spectators. In cricket grounds, as at Lord's, a cricket pavilion tends to be used for the building the players emerge from and return to, even when this is actually a large building including a grandstand. A pavilion in stadia, especially baseball parks, is a typically single-decked covered seating area (as opposed to the more expensive seating area of the main grandstand and the less expensive seating area of the uncovered bleachers).

Classical architecture

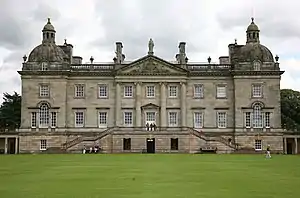

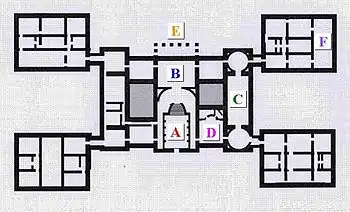

Externally, pavilions may be emphasised by any combination of a change in height, profile (a flat facade may end in round pavilions, or flat ones that project out), colour, material, and ornament. Internally they may be part of a rectangular block, or only connected to the main block by a thin section of building. The two 18th-century English country houses of Houghton Hall and Holkham Hall illustrate these different approaches in turn.

In the Place des Vosges (1605–12), Paris, twin pavilions mark the centers of the north and south sides of the square. They are named the Pavillon du Roi (“king’s pavilion”) and the Pavillon de la Reine (“queen’s pavilion”), though no royal personage ever lived in the square. With their triple archways, they function like gatehouses that give access to the privileged space of the square. French gatehouses had been built in the form of such pavilions in the preceding century.

Other uses

In some areas, a pavilion is a term for a hunting lodge. The Pavillon de Galon in Luberon, France is a typical 18th-century aristocratic hunting pavilion. The pavilion, located on the site of an old Roman villa, includes a garden à la française, which was used by the guests for receptions.

Gallery

The frontage of Houghton Hall ends in a pavilion on each side

The frontage of Houghton Hall ends in a pavilion on each side Plan of the main part of Holkham Hall, where, unlike Houghton, only a thin section connects the pavilions to the main block

Plan of the main part of Holkham Hall, where, unlike Houghton, only a thin section connects the pavilions to the main block.JPG.webp) Pavilions at each end of the facade of the Upper Belvedere, Vienna

Pavilions at each end of the facade of the Upper Belvedere, Vienna

Woodfarm Pavilion, Glasgow. An example of a more common pavilion in an urban area.

Woodfarm Pavilion, Glasgow. An example of a more common pavilion in an urban area.

A bandstand (Musikpavillon) at Bürkliplatz in Zurich, Switzerland (1908)

A bandstand (Musikpavillon) at Bürkliplatz in Zurich, Switzerland (1908) Island pavilion in the Chinese Garden, Zürich (1993)

Island pavilion in the Chinese Garden, Zürich (1993) Picnic shelter, Yarramundi Reach, Canberra

Picnic shelter, Yarramundi Reach, Canberra A stone pavilion, Indian Springs State Park, Georgia

A stone pavilion, Indian Springs State Park, Georgia A marble pavilion, Red Fort, Delhi

A marble pavilion, Red Fort, Delhi

See also

|

|

References

- "Pavilion | Architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Mitchell, James (1908). Significant Etymology. William Blackwood & Sons. p. 201.

The Latin word papilio signified originally a butterfly, but in late Latin, and even in Pliny and Tertullian, came to signify a tent, colours, or a flag. It came to signify this apparently from the flapping of the canvas, like a butterfly literally that which is spread out like the wings of a butterfly.

- Baril, Agnès (2001). Robert de Boron, Merlin, roman du XIIIe siècle (in French). Ellipses. p. 120. ISBN 978-2-7298-0301-8.

[Paveillon :] Attesté dès 1162 dans le roman de Floire et Blancheflor, ce substantif masculin est le produit du mot lat. papilionem, accusatif de papilio, -onis : papillon, puis tente en latin tardif par une métaphore bien compréhensible et attestée dès le 6e siècle. En a.f. le paveillon désignait : une papillon ; une tente conique ; une tonnelle (avec également des acceptions ponctuelles et accessoires : filet à perdrix, petite monnaie, le sein d'une mère, même).

[≈ Paveillon is attested in a 1162 novel [...]. This masculine noun is from the Latin papilionem [...], meaning "butterfly", then in Late Latin "tent", an easy-to-grasp metaphor from the 6th century. In Old French, paveillon meant "butterfly", "conical tent", "funnel trap / tunnel net [to hunt partridges]" (with the occasional and secondary meanings of "partridge net" (= tonnelle), "loose change", and even "mother's breast").]

External links

Media related to Pavilions at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pavilions at Wikimedia Commons